Lewis and Clark and the Indian Country

advertisement

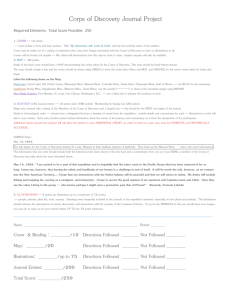

SECTION ONE Lewis and Clark and the Indian Country: 200 years of American History Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and the Corps of Discovery have long been celebrated as adventurers who “opened” the West for the United States. But what if we set aside the cliché that the explorers traveled across a “wilderness” and the traditional assumption that American expansion was “inevitable?” Viewed from this perspective, what can we learn about American history from the expedition’s encounter with Native America and the aftermath of Lewis and Clark’s journey? Lewis and Clark and the Indian Country re-examines two hundred years of American history, asking, “How did the explorers pass through the Indian country?” “What did the journey mean to them?” and “What were the consequences of their ‘adventure’?” The exhibition examines the values and traditions that united the diverse communities of the western “Indian country” at the time of the expedition and then describes Lewis and Clark’s historic encounter with the region’s inhabitants. It explores the impact of the expedition on the Indian country as well as its role in stimulating the expansion of the United States into the West. To help tell this complex story, the exhibition focuses on five of the Native American communities the Corps of Discovery met two centuries ago: the Mandans and Hidatsas of the Upper Missouri River; the Blackfeet of the Northern Plains; the Nez Perces, whose homeland straddles the continental divide, the Umatillas of the Oregon plateau; and the Chinook-speaking peoples of the lower Columbia River valley. Many members of these communities continue to live in their traditional homelands. By tracing the expedition’s role both in bringing two cultures and two histories together and in beginning the process that has woven them into the fabric of America, the exhibition reveals the richness and the possibilities embedded in our national past. SECTION TWO THE INDIAN COUNTRY 1800: A BRILLIANT PLAN FOR LIVING The people the Corps of Discovery encountered during its two and a half-year round-trip journey to the Pacific Ocean belonged to well-ordered communities. While not a country in the European sense, the region the Americans traversed two centuries ago was bound together by common values and customs. In 1800, the Native American communities in the Missouri and Columbia River regions were prosperous and thriving. They knew how to take advantage of the abundant natural resources around them, and traded for what they could not produce themselves. They had highly developed social structures to educate their children, care for their elderly, and prevent and resolve community conflicts. “Our ancestors didn’t need child welfare agencies or food stamps. They had a system, a way of life that took care of everyone. They had a brilliant plan for living.” —Frederick Baker (Mandan-Hidatsa) Creation, Gifts, and Obligations For the people of the Indian country, creation was an ongoing process; supernatural forces shaped the world in both the past and in the present. Elders explained that these forces took the form of spirit beings who had the power to influence the weather, the hunt, and the size of the harvest, and all other aspects of the natural and human world. They taught that creation was a complex process that required human participation as well as the gifts and blessings bestowed by invisible helpers. The exchange of gifts was part of the fabric of life in the Indian country. Each gift received meant that one had to be given in return. Patterns of reciprocity within and between communities facilitated social harmony. Within villages and hunting bands, gift giving discouraged greed and drew individuals into a web of mutual support. Gift giving between visitors (travelers, diplomats and traders) and their hosts, and gifts between communities, established the important relationships and alliances that helped the region to prosper and remain stable. Gifts exchanged between the spirit world and the human world were also an essential component of life in the Indian country. Gifts from the creators sustained the human world with the seasonal cycles of food, healthy children, and wisdom. In return, humans showed their respect and gratitude to the spirit beings by offering gifts of presents and prayers. Gifts from the creators could be as humble as the camas root, as powerful as the elk, or as majestic as the red cedar. The special nature of these gifts—for example, their seasonal lifecycles and their usefulness to humans—was discovered by Indian people over centuries of exploration and experimentation.Gifts exchanged between the spirit world and the human world were also an essential component of life in the Indian country. Gifts from the creators sustained the human world with the seasonal cycles of food, healthy children, and wisdom. In return, humans showed their respect and gratitude to the spirit beings by offering gifts of presents and prayers. Gifts from the creators could be as humble as the camas root, as powerful as the elk, or as majestic as the red cedar. The special nature of these gifts—for example, their seasonal lifecycles and their usefulness to humans—was discovered by Indian people over centuries of exploration and experimentation. “Beginning from the earliest times the children of the Indians were taught how they might best obtain their Weyekin [spirit helper], which would be their helper, adviser, guide and comforter, both in daily life, in war, in hunting and fishing, in business and in sickness.” —Phillip Minthorn “Portrait of Phillip Minthorn” in J. M. Cornelison’s Weyekin Titwatit Stories (Titwatit Stories) San Francisco: E. L. Mackey & Co., 1911 Newberry Library Some gifts from the creators were intended for the entire community. Others were personal—they came from the spirit helpers that guided people through their lives. These spirit helpers linked humans to the supernatural world and acted as a channel for gifts. They promoted good crops, successful hunts, and happy relationships. George Catlin “A Flathead Woman Basketing Salmon,” copied from Souvenir of the North American Indians As They Were in the Middle of the 19th Century Pencil on paper, 1852 Newberry Library The Pacific salmon is central to the traditional culture of Native people living within the Columbia River watershed. Every part of its complex life cycle has been carefully observed and incorporated into their creation stories. The salmon stories pay special attention to the fish’s changeable nature. Enduring attacks and betrayals by other animals, and by humans, Salmon survives by shifting his form; moving back and forth between youth and old age, and from an egg to a man to a fish. The salmon stories are a tool for teaching people about their origins, and about the values that hold their communities together. “Dip Net Fishing at Celilo Falls,” ca.1930 Courtesy of Washington State Historical Society, Tacoma Well into the twentieth century, Native American fishermen working the Columbia River continued to fish for salmon from the same points along the river their ancestors had fished. Their right to fish at these “usual and customary” spots, even when they were outside of reservation boundaries, was guaranteed by treaties signed by the U.S. and tribal leaders in the nineteenth century. Right Karl Bodmer “Mandan Village,” from Maximilian, Prince of Wied’s Travels to the Interior of North America London: Ackermann & Co., 1843-44 Newberry Library In traditional Native American culture, men and women had their distinct spheres, but contributed equally to the success of the community. The Mandans, for example, lived in well-organized villages of earth-built lodges clustered along the banks of the Missouri River. Each lodge housed up to three dozen people—usually groups of adult sisters with their families. The men dominated public spaces and political leadership; they were also responsible for hunting and for protecting the village from intruders. But it was the women who owned property, such as the lodges and their contents, and they were in charge of the agricultural production. They also were in control of trade, giving them considerable power within the community. Although this view of a Mandan village was executed in 1833, a generation after Lewis and Clark visited the upper Missouri River, it captures a scene that closely matches the explorers’ descriptions. Western Red Cedar (“Thuja plicata”), in Thomas Nuttall’s The North American Sylva Philadelphia: D. Rice & A. N. Hart, 1859 Newberry Library The western red cedar is indigenous to the coastal regions of the Pacific Northwest. It can grow to heights of 185 feet, and some thousand-year-old specimens have been identified. Its rot resistant and water repellent qualities were much appreciated by the inhabitants of the damp coastal areas, and they used all parts of the tree. The wood was used for everything from building materials and tools to ceremonial implements; the fibrous inner bark was used for rope, clothing and baskets. Camas (Camassia quamash) Specimen collected by Lewis and Clark Expedition Courtesy of the Academy of Natural Sciences (Philadelphia), Botany Department The camas plant was an important food source for Native communities in the Columbia River region. Women from the mountainous Nez Perce country to the Pacific coast visited well-known camas prairies to dig for the edible roots. They practiced sustainable agriculture, harvesting only the largest roots and replanting the rest. John James Audubon “Elk (Cervus canadensis),” from The Quadrupeds of North America Newberry Library A Vast Network By 1800, complex networks of trade, alliance, and competition linked every corner of the Indian country. Horses first brought to America by the Spanish were bred and traded from the Columbia Plateau to the Missouri River. Traders carried steel tools and glass beads from Europe up the Missouri and Columbia rivers, and south from Lake Winnipeg. Native groups jostled one another for space: Sioux bands moved west, Arikaras moved north, Shoshones moved south. Indian farming and trading villages along the Missouri and Columbia rivers struggled to maintain their independence and preserve their standing in the marketplace. No single power dominated the region; it was governed instead by overlapping networks of trade, travel and diplomacy. Peter Fidler Ac ko mok ki’s Map of the River System of the Rockies 1801 Hudson’s Bay Company Archives: Archives of Manitoba (HBCA G.1/25) This remarkable map provides some of the best evidence of the extensive knowledge Native people had of their environment. It also demonstrates the importance of the relationships forged between Indians and Europeans prior to the Lewis and Clark expedition. Drawn first in the snow by Ac ko mok ki, a Blackfeet leader, in February 1801, the map was copied onto paper by Hudson’s Bay Company trader, Peter Fidler. Ac ko mok ki’s map is oriented with west at the top of the page; the double line crossing from left to right represents the Rocky Mountains. The map shows two rivers running west from the Rockies, and seventeen rivers flowing east. The line down the center of the map is the Missouri River. Fidler added details regarding the Native American tribal populations in the region. Blackfeet Tribe, unidentified artist War Party Paint on cloth, before 1897 Courtesy of The Field Museum, Chicago (J. Weinstein, photo) Although warfare was a male activity, success in battle required the participation of both men and women. This painting, by an unidentified Blackfeet artist, shows a war party returning to its village. While the men were away, the women prayed for victory, and therefore shared in the glory of the men’s success. Carrying pieces of scalp given to them by their warrior relatives, the women sing songs praising the successful raid and thanking the spirit helpers for their assistance. “Lean Wolf Using Sign Talk,” in Garrick Mallery’s Sign Language Among North American Indians Compared with that among Other Peoples and Deaf Mutes Washington: United States Bureau of Ethnology, 1881 Newberry Library In addition to the Chinook trade jargon, Native American diplomats and traders used a language of signs to bridge linguistic barriers. This “sign talk” was an independent system of communication not based on any one tribe’s language. At the time of Lewis and Clark, sign talk was well established in the Indian country. This was probably the reason why the American commanders recruited George Drouillard, the half-Shawnee hunter and interpreter, to be a civilian member of the expedition. In this illustration from Sign Language Among North American Indians, Lean Wolf, a Hidatsa leader, is commenting on a recently broken agreement with the United States. He signs “Four years ago the American people agreed to be friends with us, but they lied. That is all." S. F. Coombs Dictionary of Chinook Jargon as Spoken on Puget Sound and the Northwest Seattle, WA: Lowman & Hanford, 1891 Newberry Library Across the Pacific Northwest trade between dozens of small tribal groups produced an informal language known as the Chinook trade jargon. Named after the Chinook, a local Columbia River tribe, the trade jargon actually incorporated vocabulary from a number of Indian languages, English, French and Spanish. When Lewis and Clark arrived in the Northwest, they found that use of the jargon was a common feature of Indian trade along the Pacific coast. Coombs’ glossary, published in 1891, shows the endurance of the Chinook trade jargon into the late nineteenth century. SECTION THREE CROSSING THE INDIAN COUNTRY, 1804 – 1806 Meriwether Lewis, William Clark and their company of explorers set off on the historic “Voyage of Discovery” on May 14, 1804, from Wood River, in Illinois. During 1804 and 1805, the group traveled west towards the Pacific Ocean, making the return journey to St. Louis in 1806. Their assignment was to find an easy route to the Pacific Ocean and report on the geography, people, and resources they found along the way. During their three-year trek, the men of the Corps of Discovery crossed the traditional homelands of more than 50 Native American tribes. Their interactions with Indian country peoples brought together very different worldviews, motivations and expectations. It was a cultural encounter of major proportions. Although the Corps and Indian people often had very different reasons for wanting to establish relationships, encounters between them were successful when both parties appeared to achieve their objectives. Unfortunately, differing perspectives and assumptions often led to misunderstandings between them. The expedition would have failed without Native generosity, hospitality and information. But the Americans did not always understand what they owed in return. On their way west, the Americans were eager to establish friendly ties with tribes. However, once they reached the Pacific coast, they considered themselves experts on the Indian country, and no longer felt motivated to spend time fostering relationships with Native Americans. As they headed home in 1806, this attitude, along with their anxiety about ever-dwindling supplies and their impatience about completing their mission, undermined much of the goodwill they had accumulated. Why Head West? Soon after becoming president in 1800, Thomas Jefferson proposed sending an expedition to explore beyond the Mississippi River, outside of American territory. His plan languished until April 1803, when American diplomats in Paris agreed to purchase from France “Louisiana,” the largely undocumented area between the Mississippi and the Rocky Mountains, for $15 million. Napoleon Bonaparte had acquired this land from Spain in the hopes of creating a French empire in North America. Even before Congress approved the Louisiana Purchase in October 1803, Jefferson appointed Meriwether Lewis to lead an expedition up the Missouri River and over the Rockies to the Pacific Ocean. Jefferson had a multi-faceted goal for the expedition. He wanted to expand trade with Native Americans, find a water route to the Pacific, and identify natural resources that could be exploited for commercial purposes. James L. Dick, after a painting by Rembrandt Peale Portrait of Thomas Jefferson Oil on canvas, 1805 Courtesy of Monticello/Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Inc. The Corps of Discovery Thomas Jefferson appointed his secretary, Captain Meriwether Lewis, to lead the expedition to the Pacific. Lewis, born in 1774 on a plantation near Jefferson’s Virginia home, had served as an officer in the American army in Ohio and Tennessee. To prepare him for the journey, Jefferson sent Lewis to Philadelphia to study with the nation’s leading scientists, among them Dr. Benjamin Rush, a physician, and David Rittenhouse, a noted astronomer and mathematician. Soon after his own appointment, Captain Lewis offered joint command of the expedition to his former army comrade, William Clark. Clark’s practical experience and talent for diplomacy made him an ideal expedition leader. He was also assigned the job of principal mapmaker for the expedition. The “Voyage of Discovery” was organized under the auspices of the U.S. Army. After Lewis and Clark received their commissions from President Jefferson, they began to prepare a group of men for the trip west. The Corps of Discovery, as the 27-member company is now known, began the journey on May 14, 1804. The Corps included 14 soldiers, nine civilian woodsmen, an interpreter, two boat men and Clark’s black slave, York. Later that year Toussaint Charbonneau, a French Canadian fur trader, and his Shoshone companion, Sakakawea (also known as Sacajawea), joined them. Charles Willson Peale Meriwether Lewis (1774–1809), Oil on canvas, painted from life, 1807 Courtesy of Independence National Historic Park Charles Willson Peale William Clark (1770–1838), Oil on canvas, painted from life, 1807-08 Courtesy of Independence National Historic Park Joseph Whitehouse Journal Commencing at the River Dubois [Wood River, IL] May 14, 1804 – November 6, 1805 Newberry Library Thomas Jefferson gave Meriwether Lewis explicit instructions about keeping field notes and diaries: the Corps was to record details of geography, geology, and climate; flora and fauna; and information about local inhabitants. As a safeguard against loss, they also made copies of their records. Lewis ordered all the Sergeants in the company to keep diaries as well. Joseph Whitehouse was the only enlisted man in the Corps to keep a journal. After he deserted the army in 1817, Whitehouse and his unpublished diary disappeared from history, only coming to light in the twentieth century. The Newberry Library owns two versions of Whitehouse’s journal. One is a manuscript written by Whitehouse himself. The other is in the handwriting of a professional scribe who copied it from Whitehouse’s original, making corrections and changes at Whitehouse’s request. What the Americans Knew When the Corps of Discovery embarked on its journey in 1804, the Indian country of the Upper Missouri, Rocky Mountains and Columbia River lay shrouded in mystery and fantasy. Although the British had recently mapped the coastline north of San Francisco, and Spanish and French traders were familiar with some of the Indian communities of the central plains, the Americans lacked detailed information about the North American interior. This lack of knowledge is reflected in the best-known maps of the era, in which the regions between the Mississippi River and the Pacific Ocean are shown as nearly empty. The up-to-date scientific training Captain Meriwether Lewis received from leading scientists in Philadelphia prior to the voyage was not of much help. Lewis believed the incorrect assumptions of mapmakers and scholars that the Missouri River drainage extended nearly to the Pacific, and that there were easy passes through the mountain ranges. Based on this information, he certainly had no reason to expect the journey to be as arduous and challenging as it was. “Map of North America,” from Brookes' General Gazetteer Improved (...), based on Aaron Arrowsmith’s 1802 map Philadelphia: Jacob Johnson, & Co., 1806 Newberry Library A Map of Lewis and Clark’s Track Across the Western Portion of North America from the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean Ink and pencil on paper, 1811 Private Collection In December 1810, William Clark drew a three-foot by five-foot map of his route to the Pacific for Nicholas Biddle, the Philadelphia editor preparing the official history of the expedition. Clark recommended that Biddle also consult George Shannon, a private in the Corps of Discovery. In 1811, Biddle reported that he and Shannon had modified Clark’s map “to make it illustrate the route principally.” Shannon is believed to be the draftsman for the manuscript map shown here. The map included in Biddle’s History (published by Paul Allen in 1814) is the same size, and identical in nearly every detail. The New Experts When the Corps of Discovery returned to St. Louis in the fall of 1806, the explorers were immediately acknowledged as experts on the Indian country. Sergeant Patrick Gass’s frequently reprinted Journal (1807) and Nicholas Biddle’s official History of the Expedition (completed by Paul Allen in 1814) provided vivid descriptions of the western territory. The Corps’ ideas and impressions about the region and its inhabitants informed the next generation of westward travelers. However, Native voices were not included in their reports, making it difficult for the American public to understand the complex reality of Indian life. The importance of gift giving, for example, became central to future Indian-white relations. But Native values and customs that the Corps misunderstood, or disapproved of, were labeled “backward” or “ludicrous.” The members of the Corps made the most of their expert status. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, however, achieved the greatest national prominence. Thomas Jefferson appointed Lewis governor of the Louisiana Territory in 1807, a position he held until his death in 1809. Clark was appointed the principal Indian agent for the Louisiana Territory in 1807, and he was given Lewis’s governor’s post when Lewis died (in late 1812, the northern portion of Louisiana was renamed the Missouri Territory). When Missouri became a state in 1821, Clark served as its Superintendent of Indian Affairs almost until his death in 1838. Karl Bodmer “Pehriska-Ruhpa, A Minatarree” from Maximilian, Prince of Wied’s Travels to the Interior of North America London: Ackermann & Co., 1843–44 Newberry Library George Catlin “Stu-mick-o-suks (The Buffalo’s Basket), Head Chief of the Blackfoot Tribe,” copied from Souvenir of the North American Indians as They Were in the Middle of the 19th Century Pencil on paper, 1852 Newberry Library After returning to St. Louis, William Clark controlled much of the access into the Indian country, and had the authority to license fur traders, negotiate treaties with tribal leaders, and mediate disputes between Native Americans and settlers. He also assisted travelers who wanted to explore the Indian country on their own. Relying on Clark’s aid, these travelers, such as the artists Karl Bodmer and George Catlin, played an important role in shaping public perceptions of Indian life in the nineteenth century. William Clark Account book, May 25, 1825 to June 14, 1828 St. Louis, 1825-1828 Newberry Library William Clark used the cover of this account book to compile a list of the members of the Corps of Discovery, noting who remained alive. He incorrectly listed Sergeant Patrick Gass among the deceased. Clark also noted that Sakakawea (“Se car ja we au”) was dead, contradicting the modern belief that she lived to an old age. SECTION FOUR CROSSING THE INDIAN COUNTRY – 1804 – 1806: THE EXPEDITION TIMELINE During their three-year journey from St. Louis to the Pacific coast and back again, the Corps of Discovery crossed the traditional homelands of more than 50 Native American tribes. The Indian people they met along the way provided food, horses, directions, supplies, and information about the people, geography and natural resources of the region. Without their help, the expedition would surely have failed. Most Native Americans welcomed the explorers and were generous hosts. Some tribes, however, regarded the heavily armed strangers with suspicion. Those who had already established alliances with outsiders were often less welcoming than those who saw the Americans as potential trading partners. The most accommodating tribes were those who felt threatened by neighboring groups and were seeking allies. If few Native Americans felt an immediate impact from the expedition, the information and attitudes that Corps members acquired during their three-year expedition certainly influenced the expectations and assumptions of the next generation of travelers into the Indian country. Late 1803 Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery assemble in St. Louis and begin preparations. May 14, 1804 The Corps of Discovery sets off from Camp Dubois (Wood River, Illinois). November 1, 1804 The Corps of Discovery establishes its winter camp close to five Mandan and Hidatsa villages on the Missouri River. Patrick Gass “Captain Clark and Men Building Huts,” in Journal of the Voyages and Travels of the Corps of Discovery, Under the Command of Capt. Lewis and Capt. Clarke Philadelphia: Matthew Carey, 1811 Newberry Library Karl Bodmer “Winter Village of the Minatarres [Hidatsas],” from Maximilian, Prince of Wied’s Travels to the Interior of North America London: Ackermann & Co., 1843–44 Newberry Library The Corps of Discovery established its winter camp close to five Mandan and Hidatsa villages sited along the Missouri River. Fortunately for the Americans, who needed food for the coming winter and information about the unknown territory ahead, these villages were lively trade centers, and the Indians who lived there were interested in creating alliances that could help them defend their villages against raids by rival tribes. Under the direction of Sergeant Patrick Gass, the Corps constructed Fort Mandan. The fort consisted of two rows of cabins arranged in a “V.” A picket fence completed a triangular enclosure, and a palisade surrounded the encampment. The Americans were soon visited by curious tribesmen and diplomatic, trade and social relationships quickly developed. January 1, 1805 The Americans spend New Year’s Day celebrating with the Mandan. “The Men commenced dancing … the Natives signify[ed] their approbation by a Whoop….” — Joseph Whitehouse, January 1, 1805 April 7, 1805 The Corps leaves the Mandan villages. A small party of men returns east, carrying a report and specimens back to Thomas Jefferson. Thomas Jefferson “Message from the President of the United States, Communicating Discoveries Made in Exploring the Missouri, Red River, and Washita, by Captains Lewis and Clark, Dr. Sibley, and Mr. Dunbar (...).” Washington, DC: A. and G. Way, 1806 Newberry Library Lewis and Clark compiled a summary of what they had learned thus far about Native Americans into a report to the President. Their “Statistical View of the Indian Nations” contained information regarding each tribe’s name (A), location (I), their current trading partners (J), and the dollar value of the goods they might require per year (L), as well as the market value of the furs they might produce (M). When published in February 1806, this report represented the first official word from the government on the expedition’s progress. June 2, 1805 The expedition comes to a fork in the river. Seeking the Great Falls of the Missouri, the men think the north fork is correct, but the commanders disagree. After a few days of scouting, they continue up the south fork. June 13, 1805 The expedition reaches the Great Falls, proof that the captains had been correct. August 12, 1805 Now in the Rocky Mountains, the expedition ascends the Lemhi Pass, on the present day border of Idaho and Montana. August 17, 1805 Lewis tries unsuccessfully to negotiate with a village of Shoshones for horses to cross the mountains. Detail of the Rocky Mountains from A Map of Lewis and Clark’s Track Across the Western Portion of North America, 1811 Private Collection The maps that the Corps of Discovery carried were of no help to them when they reached the eastern ranges of the Rocky Mountains. Instead of the simple line of mountains shown on those maps, the Rockies were a labyrinth of peaks and valleys. To make matters worse, the weather had already turned cold. With unexpected good luck, the Corps of Discovery came across a Shoshone band led by Sakakawea’s brother, Cameahwait. Anxious about hostile and well-armed neighboring tribes, the Shoshones eagerly traded horses and directions for iron tools carried by the Americans. Unfortunately, the Shoshone only had limited supplies to trade, and before long the Americans were in trouble again. September 5, 1805 The expedition successfully acquires horses from a band of Salish Indians. September 18, 1805 Clark and a scouting party set out to find a route through the mountains. They awake to find themselves covered in snow. September 20, 1805 After nearly starving in the Bitterroot Mountains, the Corps emerges near modern day Weippe, Idaho, where they are welcomed and fed by the Nez Perce. Edward S. Curtis “Portrait of Nine Pipes (Flathead Leader),” in North American Indian Portfolio Cambridge, MA: The University Press, 1907–1930 Newberry Library The Salish band the Corps of Discovery met in September 1805 was worried about well-armed Blackfeet raiders from the east, and anxious to have a reliable source of European trade goods. Eager to befriend the Americans, they immediately offered help. They traded their fresh horses for the Corps’ sick ones and directed the expedition toward the Lolo Trail, a centuries-old Indian track through the Bitterroot Range. The Salish were erroneously called “Flatheads,” probably because the sign gesture for them suggested they flattened the sides of their head. Nine Pipes, photographed by Edward Curtis in 1907, was a descendant of the Salish band that helped the Corps of Discovery through the mountains. Patrick Gass “Moonlight on the Western Waters,” in Lewis and Clark’s Journey to the Rocky Mountains in the Years 1804,-5-6; As Related by Patrick Gass, One of the Officers in the Expedition Dayton: Ellis, Claflin & Company, 1847 Newberry Library Although the Corps had received directions and fresh horses from the Salish, the following weeks were marked by diminishing food supplies, disappearing trails, and worsening weather. Suddenly, on September 20, Clark and a seven-man scouting party found themselves in “level pine country.” They had arrived at Weippe Prairie, a camas root digging site visited each fall by Nez Perces. To their great relief, the nearby earth lodges were inhabited. They were taken in and fed (“buffalo meat, dried salmon, berries, and roots in different states.”). The rest of the expedition arrived several days later. Luckily, the expedition had encountered another Native community seeking trading partners and military allies. Anxious to acquire guns and other trade goods, and to make contact with trading posts downriver, the Nez Perces were interested in forging alliances with strangers. October 7, 1805 The Corps of Discovery sets off from the Nez Perce village. Edward S. Curtis “Nez Perce Dugout Canoe,” from North American Indian Portfolio Cambridge, MA: The University Press, 1907–1930 Newberry Library A Nez Perce man named Twisted Hair took the Americans under his wing. He helped the captains locate a stand of pines, and work crews soon began carving the trees into dugout canoes. The Americans worked swiftly, with Patrick Gass noting in his journal that they had adopted “the Indian method of burning out” the interior of the logs. When the Americans headed off down the Clearwater River, Twisted Hair and another Nez Perce man joined them. Around the Dalles (a narrow gorge along the Columbia River), the Nez Perce men left the Corps and headed back upstream. “They Swaped to us Some of their good horses and took our worn out horses, and appeared to wish to help us as much as lay in their power.” — John Ordway, September 5, 1805 November 7, 1805 Storms on the lower Columbia River pin down the group for almost three weeks before they arrive at the Pacific. November 24, 1805 The Corps establishes Fort Clatsop, near what is now Astoria, Oregon. Tensions between the Corps and the local people arise almost immediately. William Alexander “Salmon Cove,” prepared to illustrate George Vancouver’s A Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean Watercolor, 1798 Newberry Library By the time Lewis and Clark arrived, European traders—especially Russians and British—were a common presence along the Pacific Coast from Alaska to modern Oregon. The local tribes were accustomed to the guns, iron pots and other metal goods they received in trade for sea otter pelts. As a result, they were not particularly impressed by the bedraggled Americans and their meager supply of trade goods. For their part, the Americans seemed uninterested in learning about the customs of the coastal tribes. The unpleasant damp weather of the Pacific Northwest at this time of year only added to their problems. January 1, 1806 Captain Lewis begins enforcing strict rules governing contact between the Corps and the local Indians. Newman Myrah Bartering Blue Beads for Otter Robe [at Fort Clatsop] Oil on Canvas, after 1970 Courtesy of the National Park Service, Lewis and Clark National Historical Park During their winter on the Pacific coast, Lewis and Clark grew increasingly worried about completing their mission. The company was nearly out of supplies, and worse, the commanders thought the enlisted men were spending too much time socializing with the local Indians. On New Year’s Day, 1806, Captain Lewis decreed that henceforth the gates to the Americans’ compound, Fort Clatsop, would close daily at sunset and all Indians would have to leave, adding that “troublesome” Indians could be removed at any time. Furthermore, every member of the expedition would serve guard duty, and anyone who traded or gave away government property without authorization would be tried and punished. “At sunset … both gates shall be shut.” — Meriwether Lewis, January 1, 1806 March 18, 1806 Four Americans steal a canoe from the Clatsops. March 23, 1806 The Corps leaves Fort Clatsop to begin the homeward journey. “We yet want another canoe, and as the Clatsops will not sell us one at a price which we can afford to give we will take one from them in lue of the six Elk which they stole from us in the winter.” —Meriwether Lewis, March 17, 1806 April 28, 1806 The Americans are entertained by tribesmen from the Upper Columbia who are eager to form new trade alliances. Edward S. Curtis “Umatilla Maid,” in North American Indian Portfolio Cambridge, MA: The University Press, 1907–1930 Newberry Library By late April, the Corps was far upstream from Fort Clatsop. Nearing the mouth of the Walla Walla River, they came to a Walula village. There they met Yellepit (“Friend” or “Trading Partner”), an important tribal leader. Historically, the coastal Indians, especially the Chinooks, had prevented the tribes of the upper Columbia River, such as the Walula, Yakama, Cayuse, and Umatilla, from participating in coastal trade networks. In befriending the Americans, Yellepit saw the opportunity to create new alliances that could bring highly desired trade goods, including metal tools and guns, into the area. To help solidify this valuable new relationship, Yellepit hosted a grand celebration for the Americans, inviting members of other local tribes—perhaps as many as 550 guests in all. The Americans, however, may not have understood the diplomatic implications of the festivities. Although this photograph is from the early twentieth century, it gives us a good idea of the festive garb that was probably worn during the 1806 celebrations. May–June, 1806 The expedition rejoins the Nez Perces on the west side of the Bitterroot Mountains. They must wait for the snow to stop before they are able to continue eastward over the range. July 3, 1806 After crossing the Bitterroots, the Corps splits into two parties. Clark heads down the Yellowstone. Lewis takes a shortcut to Great Falls and explores the Marias River. July 27, 1806 The expedition has its only deadly encounter with the Indians, killing two Blackfeet youths. “Captain Lewis Shooting an Indian,” in Journal of the Voyages and Travels of the Corps of Discovery, under the Command of Capt. Lewis and Capt. Clarke Philadelphia: Mathew Carey, 1812 Newberry Library In late July 1806, Lewis and a small scouting party set out to explore the Marias River. In the hills near the Two Medicine River, they encountered eight young Blackfeet men. After a cordial meeting, they decided to camp together, and Lewis presented them with a small American flag and a peace medal. He told them that the Americans were allies with the Nez Perce, Salish, and Shoshones, not realizing they were traditional enemies of the Blackfeet. The following morning, the young Indians, perhaps alarmed by Lewis’s speech, grabbed some guns and tried to escape. Lewis’s group recovered their weapons, only to discover that the fleeing Blackfeet were trying to steal their horses. As Lewis led his men in pursuit, Private Reuben Fields grabbed one of the Blackfeet and stabbed him in the heart. Lewis shot a second man in the stomach, mortally wounding him. John Reich Jefferson Peace and Friendship Medal Philadelphia: John Reich, 1801 (silver) Newberry Library It was common practice for European governments to give medals to Indian leaders to seal alliances. The Corps of Discovery left St. Louis with nearly 90 medals in at least four sizes and distributed them liberally to their hosts. Most of the medals were the so-called Jefferson peace medals. After the Americans’ fatal encounter with the young Blackfeet, Lewis retrieved the flag and peace medal he had given out the night before and set the Indians’ baggage ablaze. To add insult to injury, he placed the medal around the neck of one of the dead youths. “I … left the medal about the neck of the dead man that they might be informed who we were.” —Meriwether Lewis, July 27, 1806 August 12, 1806 Downstream from the mouth of the Yellowstone, the two parties of the Corps reunite. Olin Dunbar Wheeler “Portrait of Wolf Calf [in 1895],” in On the Trail of Lewis and Clark New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904 Newberry Library In 1895, anthropologist George Bird Grinnell interviewed Wolf Calf, a 102-year-old Blackfeet man, about the encounter between the Corps of Discovery and the Blackfeet youths. (See “Captain Lewis Shooting an Indian,” below). The young men, Wolf Calf reported, did not know anything about the Americans. They had tried to capture the strangers’ guns and horses out of youthful bravado. “Captures” of this kind were a common part of the Plains warriors’ competitive culture. According to Grinnell and Wheeler, Wolf Calf, shown here on horseback, was one of the young men who met Lewis and Clark. September 23, 1806 The Corps of Discovery arrives in St. Louis. SECTION FIVE A NEW NATION COMES TO THE INDIAN COUNTRY Little changed in the Indian country in the first years after Lewis and Clark completed their expedition. The Corps of Discovery had failed to find an easy route to the Pacific and few people wanted to follow their difficult path. However, the information the explorers compiled vastly widened the “mental map” of the continent, and their reports encouraged many American political and business leaders to think about continuing the national expansion that began with the Louisiana Purchase. In the early years after the expedition, the highly profitable fur trade encouraged the construction of outposts and new settlements. By the middle decades of the nineteenth century, national and international events—the Texas revolution against Mexico, the creation of the nation’s border with Canada at the 49th parallel, and the California gold rush—meant that information provided by the Corps of Discovery was more important than ever. Once the American claim to the land seemed secure, the traders were followed by miners and homesteaders who, unlike their predecessors, saw no advantage to building relationships with Native Americans. Instead, these land-hungry newcomers preferred to push Indians aside. The coming of the railroads completed the transformation of the region. This process was not a peaceful one, rather it was punctuated by violence and military conflict. In the nineteenth century, American westward expansion impacted all of the Indian country. Here, we focus on some of the activities that transformed the tribal areas along the route of the Corps of Discovery—the fur trade, mining, homesteading, ranching, and the “Americanization” campaign. By century’s end, Americans had a new name for the Indian country. They now called it “The West.” Homesteaders In the summer of 1855, Isaac Stevens, the Oregon Territory’s first governor, met with the leaders of the upper Columbia River tribes to negotiate a treaty covering large portions of the modern states of Washington, Oregon and Idaho. His main argument was that an influx of non-Indians into the region was inevitable and that a treaty between the tribes and the federal government offered the Indian people the best protection against encroachment by newcomers. On June 9, 1855, the Walla Walla, Cayuse, and Umatilla Treaty was signed. Similar agreements were also reached with the Nez Perces, the Middle Columbia tribes, and the Yakamas. In the treaty, the signing tribes ceded 6.4 million acres to the United States. In return, they were guaranteed rights over the remaining territory. They also reserved the right to fish, hunt, and gather traditional foods in “usual and customary” locations on the ceded lands. The federal government pledged to provide them with schools, housing, health care, and various subsidies. Unfortunately, promotional materials that advertised homesteading opportunities downplayed the Native American presence in the West. Can you stop the waters of the Columbia river from flowing on its course? Can you prevent the wind from blowing? Can you prevent the rain from falling? Can you prevent the whites from coming? You are answered No! Like the grasshoppers on the plains; some years there will be more come than others, you cannot stop them. —Joel Palmer, Superintendent for the State of Oregon, June 2, 1855 The Fur Trade In the nineteenth century, the already well-established American fur trade was transformed into a truly transcontinental industry. Built on the abundant supply of fur-bearing animals in the Indian country, it also relied on the diplomatic skill of the fur traders (Corps of Discovery veterans John Colter and George Drouillard were among the pioneers of this burgeoning enterprise) and access to Native American labor. But if the fur trade made John Jacob Astor America’s first millionaire, it brought profound changes to the Indian country. The growth of commercial trading posts disrupted Native American economic systems by encouraging Indian people to abandon their mixed economies of subsistence and trade, in favor of a more purely cash economy. Worst of all, the outsiders also brought devastating new diseases to the Indian country. I have done everything that a red skin could do for them, and how have they repaid it! With ingratitude! … I have been in many battles, and often wounded, but the wounds of my enemies I exalt in, but today I am wounded, and by whom? By those same white Dogs that I have always considered, and treated as Brothers. —Mato Tope (Four Bears), quoted by Francis Chardon John James Audubon and John Bachman “Beaver,” from Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America New York: V.G. Audubon, 1846-1854 Newberry Library In the first years of the nineteenth century, mountain men were amazed by the number of western beaver they found, and delighted that the animal could be hunted year round. However, within a generation, the beaver population was depleted by over-hunting, so hunters and traders turned to commercial buffalo hunting to sustain themselves. George Catlin “Mah to toh pa (The Four Bears),” copied from Souvenir of the North American Indians As They Were in the Middle of the 19th Century Pencil on paper, 1852 Newberry Library In the summer of 1837, American Fur Company trader Francis Chardon was working at Fort Clark, the post adjacent to the earth lodge villages that Lewis and Clark had first visited in 1804. There, he witnessed a devastating smallpox epidemic that swept through the Mandan settlements. Chardon recorded the dying words of Mato Tope (Four Bears, 1795–1837), a popular Mandan leader who had been a child when the Corps of Discovery wintered with his tribe. Although devastated by smallpox and other diseases, the Mandans reorganized their villages and lived on. Unidentified Photographer “Arikara Children: Susie Nagle and Mary Walker” Fort Berthold Reservation, c.1890 Newberry Library Native American communities often used family ties to create and strengthen relationships with outsiders. As a result, relationships between Native women and European fur traders had long been a familiar feature of Native life. As the number of fur traders multiplied in the West, the population of mixed-heritage children also grew. These children were accepted in Indian communities, but were often scorned as “halfbreeds” by racially conscious whites. This photograph was taken at Fort Berthold, near the site of the Mandan villages. Miners Gold (and other mineral resources) drew thousands of Americans into the Indian country. One of the most traumatic gold rushes of the nineteenth century hit the Nez Perces in the early 1860s, when gold was discovered on their reservation land, near where the Corps of Discovery had built canoes in the fall of 1805. The resulting invasion by miners, who were often unaware they were trespassing on tribal property, set off disputes between the tribe and the miners. Furthermore, there were arguments within the tribe over how best to respond to the crisis. The story repeated itself in 1874, when Colonel George Armstrong Custer led an expedition through the Black Hills to investigate rumors of gold. His report that indeed, there was gold, set off a rush to the hills. This time, thousands of prospectors trespassed on Sioux reservation lands. In 1877, the tribe was forced to cede the Black Hills to the United States. Daniel W. Lowell & Co. Map of the Nez Perces and Salmon River Gold Mines in Washington Territory. Compiled from the Most Recent Surveys San Francisco: Whitton, Waters & Co., 1862 Newberry Library Published at the height of the Nez Perce gold rush, this map showing the gold mines of the Washington Territory (now central Idaho) makes no mention of the Nez Perces or the fact that the new mines were located on tribal land. Edward S. Curtis “[James] Lawyer” in North American Indian Portfolio Cambridge, MA: The University Press, 1907-1930 Newberry Library Unwilling to force miners from tribal property, federal officials convened a treaty council in May 1863 and pressured a group of Nez Perce chiefs to accept a 90 percent reduction of their homeland. A Nez Perce tribal leader named “Lawyer” was strongly in favor of negotiating with the U.S. government. A direct descendant of Twisted Hair (the man who had guided Lewis and Clark down the Columbia in 1805), Lawyer also participated in the Walla Walla Treaty Council of 1855. When photographer Edward Curtis visited the Nez Perces in 1905, he took this photograph of Lawyer’s son, James Lawyer (note the peace medal he is wearing). Unidentified Photographer “General John Gibbon and Chief Joseph on the Shore of Lake Chelan [Oregon] 1889” Newberry Library In June 1877, several Nez Perce leaders living outside the tribal reservation began to resettle within its boundaries. At the same time, a few young Nez Perces attacked some white settlers, triggering military retaliation by the United States Army. Six hundred Nez Perces fled across the Bitterroot Mountains to Montana, trying to reach Canada, but most surrendered in October, just short of their goal. Their spokesman was a leader the whites called “Chief Joseph.” Exiled to Indian Territory (in present-day Oklahoma) until 1885, Chief Joseph eventually returned to the Northwest, but was forbidden from settling on the Nez Perce reservation. In this 1889 photograph, he is shown seated with General John Gibbon, one of his adversaries during the summer of 1877. Ranchers After the American Civil War, ranching attracted thousands of outsiders to the Indian country. These newcomers quickly used up the available public lands, and urged federal authorities to permit them to graze their herds on what they saw as unused Indian lands. Indian communities along the Lewis and Clark route were particularly hard hit by these changes. Some Native people, however, found that ranching offered an attractive way to make a living. The annual cycle of ranching activities was not much different than the seasonal cycle around which traditional Indian life was organized. Unfortunately, tribal ranching ventures did not have access to land beyond reservation boundaries, or to bank loans and other financial support. As a result, successful Indian cattlemen could be self-sufficient, but they were rarely able to compete with large non-Indian ranches, or influence national cattle or land use policies. Frank Linderman and Winold Reiss “Plume” in Blackfeet Indians of Glacier Park St. Paul, MN: Brown & Bigelow, 1940 Newberry Library At the turn of the twentieth century, the Blackfeet sold a portion of their tribal land to finance the creation of family cattle herds. Blackfeet ranchers fattened their livestock on hay they raised along streams running east out of the Rocky Mountains and used the Great Northern Railway to ship their steers to markets in St. Paul and Chicago. The ranchers were constantly threatened by weather and the shifting priorities of reservation bureaucrats, but by 1900 the tribe had registered 500 brands, and the community’s herds totaled more than five thousand head. This portrait of Blackfeet rancher Plume reflects the modest prosperity that Indian cattlemen enjoyed in the early years of the twentieth century. Painted by Winold Reiss, the portrait was part of a promotional packet distributed by the Great Northern Railway. Unidentified Photographer “Cattle Ranching on the Ft. Berthold Reservation” Courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society, Gilbert Wilson Photograph Collection The U.S. Indian Office first issued cattle to Indians to raise for food, but in the 1890s federal officials began encouraging the tribes to develop commercial herds as a way to generate jobs and cash. The Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara families whose lands were combined to form the Fort Berthold reservation began building such a herd in 1891. Within a decade, ranching became a major aspect of life there. In winter, Indian ranchers kept the cattle close to their Missouri River homesteads, while in summer they set the animals loose on the surrounding prairies. These photographs of the fall routine at Fort Berthold show how quickly Indians The “Americanization Campaign” By 1900, Native Americans could no longer maintain their traditional ways of life. Tribal communities faced constant disruption from new governments, new businesses, and new settlers. In an effort to help tribes adapt to these conditions, government agents, teachers, and state-subsidized missionaries encouraged Indians to purchase private property, convert to Christianity, and give up speaking their tribal languages. U.S. authorities operated four types of schools for Indians: off-reservation boarding schools; reservation boarding schools; day schools; and mission schools. The schools operated under rules issued by the Indian School Service, a division of the Office of Indian Affairs. Some of these rules became excuses to suppress all aspects of traditional culture; others were openly punitive. Native Americans did not want to abandon their traditional lifeways, but they understood the necessity of adapting to the changing world around them. Ironically, non-Indians considered Indian efforts to change with the times a sign of weakness. These schools should be conducted upon lines best adapted to the development of character, and the formation of habits of industrial thrift and moral responsibility, which will prepare the pupil for the active responsibilities of citizenship. —United States Office of Indian Affairs Rules for the Indian School Service Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1898 Olin Dunbar Wheeler “Day School at Independence” 1904 Newberry Library Federal officials insisted that in order to become “civilized,” Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara families would have to abandon their traditional riverfront villages and move into single-family households on individual pieces of property. They also forced Indian families to send their children to schools where they would learn English and vocational skills. This photograph, taken in 1904, shows a government school teacher, his family and a group of his students gathered in front of a school building at Fort Berthold, near the site of the Mandan villages visited by Lewis and Clark a century earlier. “The members of the tribal council sign this contract with heavy hearts. Right now, the future does not look so good to us. Our Treaty of Fort Laramie made in 1851, our tribal constitution, are being torn to shreds.”—George Gillette, May 20,1948 SECTION SIX THE INDIAN COUNTRY TODAY Today, Indian people living in the areas visited by Lewis and Clark belong to two nations. They are American citizens who work, pay taxes and send their young people to serve in the military. At the same time, they belong to tribal nations which are trying to sustain distinctive ways of life and are determined to carry on the values and practices of their ancient cultures. Indian communities are subject to the same pressures and problems facing all communities with high levels of poverty. But they are being empowered by a new understanding of their history, traditions, and tribal languages. Customs and values from the past are helping to guide tribal peoples as they decide for themselves what it means to be Indian in the twenty-first century. This section of the exhibition presents just a few of the ways in which Native communities are working successfully to defend, rebuild and sustain the Indian country. Who am I? Am I the person of my past Am I the person who is lost Who am I? I hear tales of my ancestors I feel my chest fill with pride Knowing where I am from But . . . I can never live as they did So my past is my past Who am I? . . . Excerpted from “Who Am I?” by Roger D. White Owl (Mandan/Hidatsa), first published in /Tribal College Student/, Fort Berthold Community College, Summer 1999 Used with permission from the author Environmental Issues In the summer of 1855, American Indian tribes living along the Columbia River ceded millions of acres of tribal land to the United States. In exchange, they received secure titles to reservations where they could live undisturbed. They also reserved the right to continue traditional practices (such as fishing, food gathering, and religious ceremonies) in the “usual and customary” areas outside the reservation boundaries. Since that time, the region has suffered serious environmental degradation. Today, the tribes that signed the 1855 Treaty are actively involved in protecting and restoring these damaged areas. They regard it as their inherited responsibility to care for the natural resources that are so central to their traditions and identity. Unidentified Photographer “Members of the Colville Tribe at Kettle Falls, on the Columbia River during the Ceremony of Tears, 1940” Courtesy of the Northwest Museum of Art and Culture, Spokane The Columbia River tribes performed the Ceremony of Tears to commemorate the salmon and the salmon habitat to be lost when the area was flooded by the construction of the Grand Coulee Damn Above Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission Logo The tribes living within the Columbia River watershed recognize that environmental restoration and protection is a regional issue best addressed cooperatively. In 1977, the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission (CRITFC) was formed to coordinate the fish management policies of four of the Columbia River treaty nations: the Umatilla, Nez Perce, Warm Springs, and Yakama. “Wildlife Mitigation Agreement for Dworshak Dam, Bonneville Power Administration, State of Idaho, 1992” “Memorandum of Agreement between the United States Fish and Wildlife Service and the Nez Perce Tribe and for Joint Management of the Dworshak National Fish Hatchery, 2005” “Memorandum of Agreement between the State of Idaho and the Nez Perce Tribe Concerning Coordination of Wolf Conservation and Related Activities in Idaho, 2005” Eight years after the Walla Walla treaty was ratified in 1855, the Nez Perces agreed to reduce the size of their reservation, but they did not abandon their sense of responsibility for their original homeland. The Nez Perce Tribe has entered into numerous agreements with state and federal agencies which focus on environmental issues affecting the traditional tribal lands outside present reservation boundaries. Together with these non-Indian agencies, the Nez Perce tribe develops environmental protection, restoration, and management plans. The agencies then contract with the tribe to complete the work outlined in the plans. Informational Brochures from the Nez Perce Tribe Land Services Program; BioControl Center; and Environmental Restoration and Waste Management (ERWM), ca. 1996-2003 The Nez Perce Department of Natural Resources develops and manages a variety of environmental protection and restoration programs, including programs for wildlife protection, watershed restoration, sustainable agriculture, environmental and waste management, conservation, air quality monitoring, and forest management. “Does the earth know what is happening to her? Does the earth know that these lines are being drawn across it? Who is going to speak for the earth?” —Otis Half Moon (Nez Perce), quoting a tribal elder who signed the 1855 treaty with the United States Retaining Traditions Throughout the Indian country, the U. S. government used federally-regulated schools to suppress traditional Indian ways, and turn Indian people into “real” Americans. Today, Native Americans are using Indian-run schools to revitalize their communities. Community-controlled grade schools, high schools, and tribal colleges are finding innovative new ways to bringthe study of Native American history and traditional cultural practices into the classroom. As they learn more about themselves, these young people are being empowered to determine the direction of the Indian country in the twenty-first century. Fort Berthold Community College New Town, ND Fort Berthold Community College, founded in 1973, serves the Three Affiliated Tribes (Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara) of the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation. The college awards associate degrees in traditional academic subjects, provides teacher training, and offers vocational certification. FBCC has also taken a leading role in efforts to preserve cultural traditions by offering courses, encouraging local artists and writers, and providing an institutional home for cultural preservation activities. Student at Nizipuhwahsin “Real Speak” School Browning, MT: 2000-2004 Nizipuhwahsin is a language immersion school, meaning that all instruction takes place in Blackfeet. The curriculum at the school integrates traditional academic subjects with specialized language training. It was designed by staff of the Piegan Institute, and conforms to Montana state education guidelines for kindergarten through the eighth grade. Students who have graduated from Nizipuhwahsin have gone on to achieve significant academic success in high school. Student work from Nizipuhwahsin “Real Speak” School Browning, MT: ca. 2004 Piegan Institute Informational Brochure Browning, MT: ca. 2000 The Piegan Institute was founded in 1987 to promote the study of the Blackfeet language and develop programs for reviving its use. Its most innovative program is Nizipuhwahsin “Real Speak” School, a Blackfeet language immersion school serving students through the eighth grade. Today, only three percent of all Blackfeet—mostly elders—are fluent speakers of their language. The goal of Nizipuhwahsin is to create a new generation of speakers. The Piegan Institute is part of a larger international movement to preserve and revive indigenous languages. Staff from the institute often consult with staff from other similar organizations. Preparing for the Tricentennial “Will we still believe in our distinctive Indian identities?” —Frederick Baker (Mandan-Hidatsa) “Will the United States continue to uphold our treaties so that we can continue to celebrate the gift of salmon?” —Marjorie Waheneka (Cayuse/Palouse/Warm Springs) “Will we speak our tribal languages?” —Darrell Kipp (Blackfeet) “Will all Americans join us as we speak on behalf of the earth?” —Otis Half Moon (Nez Perce) “Will Indian art forms continue to inspire both Native Americans and others?” —Pat Courtney Gold (Wasco-Wishram) CREDITS Lewis & Clark and the Indian Country: Two Hundred Years of American History was originally organized by the Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois. The traveling exhibition, organized in partnership with the American Library Association, is made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities: great ideas brought to life. Additional support comes from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. At the Newberry, the exhibition was supported by grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The Sara Lee Foundation was the Lead Corporate Sponsor of the exhibition. Major underwriting has been generously contributed by Ruth C. Ruggles. Additional support for the exhibition and related public programming was received from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and the National Park Service’s Lewis and Clark Challenge Cost Share grant program. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this exhibit do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Many people have contributed to the success of this project, and deserve our sincere appreciation. Curator: Frederick E. Hoxie, Swanlund Professor of History, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Project Director: Riva Feshbach, Newberry Library Project Consultants: Frederick Baker (Mandan and Hidatsa), Fort Berthold Community College Loretta Fowler, University of Oklahoma Pat Courtney Gold (Wasco-Wishram), Independent Artist Otis Halfmoon (Nez Perce), National Park Service Darrell Robes Kipp (Blackfeet), Piegan Institute Rosalyn LaPier (Blackfeet/Metis), Piegan Institute Jacki Thompson Rand (Choctaw), University of Iowa James Ronda, University of Tulsa Marjorie Waheneka (Cayuse/Palouse/Warm Springs), Tamástslikt Institute Photography: Catherine Gass, Newberry Library; Landscape photography by Richard Mack, from The Lewis & Clark Trail: American Landscapes, Quiet Light Publishing, Evanston, IL, 2004. Exhibition Tour Coordination: American Library Association, Public Programs Office, Chicago, Illinois Exhibition Design: Chester Design Associates, Washington, DC and Chicago Indian Voices and the Lewis & Clark and the Indian Country Web site (www.newberry.org/lewisandclark) were produced under the direction of Sally Thompson, University of Montana.