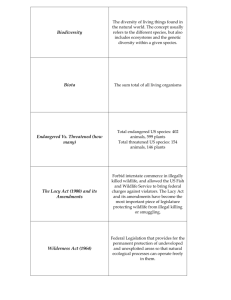

A sample report prepared by Costa Rica on the protected areas

advertisement