Acoustic Imaging Methods

advertisement

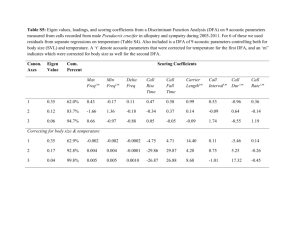

INVESTIGATION OF PHYSICO-MECHANICAL PROPERTIES AND LOCAL DISTRIBUTION OF METAL MICROSTRUCTURES USING SCANNING ACOUSTIC MICROSCOPY Professor Roman Gr. Maev University of Windsor Centre for Imaging Research and Advanced Material Characterization, Windsor, N9B 3P4, Ontario, Canada ABSTRACT This presentation deals with the analysis of the potential of a fundamentally new method – Scanning Acoustic Microscopy – for studying the physical microstructure and the dynamic processes of failure in advanced materials of the most diverse nature, including metals and various metal alloys, matrix metals, multi-layer systems etc. Work in the ultrasonic microvision technology has given rise to a new experimental means for generating images of the interior of matter with a resolution comparable to that of light micrographs, with many practical applications. INTRODUCTION There are at present several effective methods for the investigation of physicomechanical properties and local distribution of microstructures in various advanced materials. Most important among these are electron and optical microscopy, a number of spectral techniques, including traditional ultrasonic nondestructive materials characterization and evaluation (NDE) methods. The role of NDE is changing and will continue to change dramatically. It has become increasingly evident that it is both practical and cost effective to expand the role of NDE and quality control to include all aspects of production process and to introduce it as much as earlier in the manufacturing cycle. Today, and even increasingly in the future, using advanced optical, thermal, ultrasonic, laser-ultrasound, acoustic emission sensors, vibrational, electro-magnetic, X-ray technique, etc., as well as modern measurement technique, along with signal/data processing, on-line information on the processing conditions can be continuously generated. Real-time process monitoring for more effective and efficient real-time control of various processes and as a result improved vehicle manufacturing quality control inspection and reliability will now become a practical reality. The new materials structures, joints, parts, components made from various materials demand the innovative applications of modern NDE techniques to monitor and control as many stages of the production process as possible. Simply put, intelligent advance manufacturing is impossible without integrating modern nondestructive evaluation into the production system. Works in the imaging systems, including optical, infrared, microwave, ultrasonic, etc. technique, has given rise to a new experimental means for generating images of the interior of matter with many practical applications. 694 BACKGROUND Acoustical imaging is well-known as a powerful tool for studying the microstructure and properties of materials, and it has attracted the efforts of research groups in different countries. Actually, high-resolution acoustic imaging, or acoustic microscopy is a relatively new technique. The idea of a microscope using sound rather than light was first put forward by a Russian scientist (Sokolov, 1934). However, due to the limitations of existing technology, it was many years before high-resolution acoustic imaging was actually realized. The first prototype acoustic microscope was built in the USA, (C. Quate, Stanford University) in 1974. The industrial application of acoustic microscopy is still a developing field of study. The activity of most groups in the world is focused on the development and application of acoustic microscopy to surface and nearest subsurface layers of specimens. For example, the group of Prof. A. Briggs (Oxford, UK) [1] has proposed effective methods of characterizing surface and subsurface cracks, plastic deformations and other surface and subsurface defects in materials. Prof. B. KhuriYakub (Stanford, USA) [1,2] and his group are successfully developing quantitative methods for characterization of elastic properties at the surfaces of solids. Prof. J. Kushibiki (Tohoku Univ., Japan) [1] is developing the line-focus-beam method to study surface elastic anisotropy; and Prof. G. Wade (Santa-Barbara, USA) [1,2] has worked on signal and image processing from surfaces and subsurface regions. Centre for Imaging Research and Advanced Materials Characterization (Windsor, Canada) have developed expertise in the visualization of structures deep inside objects. The results of our research on transmission acoustic microscopy is well appreciated for the study and NDE of films and thin specimens New methods was developed for visualizing bulk microstructures of anisotropic materials and have successfully applied it to investigations of defect microstructure of advanced crystalline materials, including carbon materials, high-Tc superconducting crystals, various metals, including austenite steel, aluminum alloys and others [2]. Our group also has developed various short-pulse acoustic microscopes for bulk microstructure characterization of materials and currently develop next generation of 3D imaging scanning acoustic microscope [3}. In the Centre have designed and built a few different prototypes of hand-handle acoustic imaging systems with 2D multilens and 2D matrix array transducers. Based on that knowledge and research experience, we have studied the microstructure and properties of various advanced materials as well as have undertaken examination of various welding NDE of casting aluminum alloys, riveting and resistance spot-weld quality control inspections for the automotive industry, among others. ACOUSTIC IMAGING METHODS The scanning acoustic imaging technique uses ultrasonic pulse for near-surface and bulk structure examination. A single narrow pulse generated by the transducer travels towards the sample surface where it is partially reflected back while the reminder propagates through the specimen interacting with internal structure. The reflected signal, which is received by the transducer generally, contains a peak corresponding to the surface reflection succeeded by echoes reflected from the internal structure These echoes reach a transducer after a time delay that depends on the ultrasound velocity in a particular area of the sample. The amplitudes of the reflected and 695 transmitted waves are a function of the acoustic properties of the material at each scanning point. Echo reflection can be caused by different kinds of non-homogeneity or discontinuity (for example: phase and grain boundaries, voids, inclusions and cracks) [3–9]. In our research we use two kinds of desktop acoustic microscopes and a hand-held array transducer. The first one is ELSAM (Ernst Leitz Scanning Acoustic Microscope) manufactured by LEITZ Ltd. The second ultrasonic system is an ultrashort pulse reflection ultrasonic microscope (SPSAM) designed by the Acoustic Microscopy Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Moscow, Russia). ELSAM LEITZ has developed the ELSAM, with a frequency range from 0.1 to 2.0 GHz, six magnification selections with a maximum resolution of 0.3µm [4]. It can operate both as an optical reflection microscope and as an acoustic microscope. The scanning of the acoustic objective is accomplished with the oscillator coil drive. The microscope produces 512 512 pixel images with a scan area starting from 0.8 0.8 mm down to 40 40 µm. Its acoustic focusing system uses a plano-concave sapphire (Al2O3) lens with a zinc oxide piezo-electric transducer and a wide aperture. So-called continuous mode is used, that is the excitation electric signal is produced by a high frequency generator and it consists of several periods [10]. The ELSAM acoustic microscope was designed mainly for a high-resolution surface and subsurface investigation and it does not allow for deep structure imaging. Optical Unit Oscilloscope Acoustical Unit Adjustable Table Control Unit Fig. 1. ELSAM acoustic microscope Fig. 2. Desktop SPSAM acoustic microscope SPSAM This wide-field, short pulse SAM operates with a frequency range between 25–100 MHz and various lens apertures [3, 5]. The frequency and design of each of the lenses was based upon the analytical and numerical calculations of the propagation of focused ultrasonic pulses through aluminum casting samples. Short probe pulses (3–5 oscillation periods) allow for the resolving of fine microstructural details at a depth of 5 mm, with a resolution of 50–150 µm. The short probe pulses are partially reflected back to the microscope whenever a nonhomogenous object is encountered. The received reflected signal is stored in a personal computer where special software can recognize and process the reflections 696 from different internal defects and generates visual output. This output will then be analyzed and interpreted by researchers. A mechanical scanner is used to provide one and two-dimensional movements of the acoustic sensor for B-scan and C-scan representation of the specimen's internal structure. A scanner with a scanning area of 80 120 mm, a maximum mean scanning velocity of 2 mm/sec and a precision of 0.05 mm was used. A computer received the collected data and provided material interface detection and recognition as well as A-scan, B-scan and C-scan imaging. The pulse method features an adjustable time-delay gate that is used to collect individual echo-signals. All of the collected signals from a scanning area of interest, at various depths of penetration, are used to represent the C and B acoustical images [2]. Therefore, the delay gate is useful to study reflected signals from a particular region. The depth of penetration of acoustic waves is inversely proportional to the density, acoustic velocity and attenuation in the material. With respect to image processing, current methods are based on amplitude and delay time measurements of the demodulated reflected pulses. The processing of fully digitized signal waveforms permits one to increase measurement accuracy and to investigate the frequency dependence of attenuation. However, special methods of digital processing are required if the return signals are greatly overlapped or transformed. This occurs when the thickness of an inclusion is about one wavelength or it is too deep to be detected using a high frequency probe. During experimental preparations, new algorithms for digital signal processing were developed based on non-linear parameter estimation. This method permitted us to separate pulse responses reflected from each inhomogeneity and therefore measure their time delay and amplitude [1, 3, 5]. 2D Matrix Transducer Matrix and array transducers offer several enhanced capabilities in imaging and beam forming compared to a single transducer scanning system. The matrix transducer technology makes fast data acquisition and imaging possible, while using motionless transducers. Advanced technologies such as micro-machining and IC manufacturing can produce matrices of thousand elements of less than 0.1 mm in size, creating an acoustic analog of CCD camera [6]. This size is essential for phased arrays, given the element size must be around half a wavelength for efficient beam-forming [7]. However, for matrices not using phased principles to build the acoustic beam, such small elements represent a disadvantage. Matrix transducers having such a high density can only operate in the pick-up mode due to power dissipation restrictions. Moreover, acoustic wavelengths at megahertz frequencies are at least 103 times larger than the light wavelengths, thus, there seems to be no reason to go down to the micron range resolution [8]. One of the array transducers used in our study has the diameter of 8.0 mm and contained 52 emitting-receiving broadband elements with the central frequency around 20 MHz; the matrix period was 1.0 mm, individual elements being of 0.740.74 mm2 square. The elements were switched one at a time using a custom coaxial relay multiplexer interfaced with the parallel port. Experimental data have been acquired with a USD-15 (ultrasonic pulser Krautkramer) connected to a TDS520 (Tektronix digitizing oscilloscope), digital data were transferred to the PC via a GPIB interface card. The sampling rate (TDS-520) used in the experiments was 500 697 MSamples/s. For image smoothing and quality enhancing various 2D interpolation algorithms were used. The imaging capability of the system generally depends on the penetration depth of the transducer. The penetration depth drops with the decreasing size of the element due to the beam divergence and the increasing electrical mismatch with 50 Ohms transmitters and receivers. In general the image quality gets worse for smaller and deeper reflectors. Images obtained on 1.0 and 2.0 mm flat-bottomed holes drilled inside a 319 aluminum casting sample are given in Figures 3 and 4. The holes were grouped by four for the depth range from 1.0 to 8.5mm separated by 0.5 mm depth step within a group. Featured C-scans were obtained to 8.5 mm deep for 2.0 mm flat-bottom holes, however reflectors of 1.0 mm diameter were only clearly observed to 4.5 mm deep. Fig. 3. C-scans of 1 mm flat-bottom reflectors located in the depth range: a) 1.0–2.5 mm; b) 3.0–4.5 mm (0.5 mm step). Fig. 4. C-scans of 2 mm flat-bottom reflectors located in the depth range: a) 1.0–2.5 mm; b) 7.0–8.5 mm (0.5 mm step). In Figure 5 example of an imaging application for the matrix transducer portable device is given. The generated acoustic images represent laser spot weld samples of 0.75 and 1.0 mm thick. Surface burn marks were respectively around 3.0 and 7.0 mm. (a) (b) (c) (d) Fig. 5. Acoustic images of laser spot welds generated with a desktop scanning acoustic microscope and corresponding images obtained with the 52-element array: (a), (b) 0.75 mm thick steel plate approximately 3.0 mm. weld; (c), (d) 1.0 mm thick steel plate around 7.0 mm weld. 698 Fig. 6. Acoustic images of copper wires inside the flexible printed circuit board, which is incorporated into 1.5 mm thick plastic cover. Matrix transducer is capable to visualize location and orientation of the flexible printed circuit board (PCB) inside the plastic. In Figure 6, images of 0.2 mm thick and 2 mm wide wires are shown. The separation between the wires in the right image is 1 mm. HIGH-RESOLUTION ULTRASONIC INSPECTION METHODS FOR JOINT INSPECTION The traditional methods of any joints monitoring are combinations of visual inspection, pry testing and destructive tests, like in the resistance spot welds, with hammer and chisel. The only effective non-destructive method has been the ultrasonic pulsed echo technique based on an evaluation of ultrasonic echo patterns in a specimen. The current ultrasound technique is capable of determining the approximate parameters of the joint. Disadvantages of that technique and method are evident: a wide range of ambiguity in treating echograms; a high sensitivity of the result to the alignment of the transducer perpendicular to the surface; the dependence of the results on operator experience and skill; the impossibility of building the method into an on-line process; etc. The hottest NDT problem today is high-resolution inspection of welding joints. The problem of inspection for many-layered (2 or more layers) joints formed by spotwelding or diffusion welding is under investigation. Using acoustic imaging systems with short probe pulses provides a way to visualize small-scale failures of contact and other defects at different depths. For spot welding acoustic imaging systems makes it possible to inspect fine details of internal areas of joints in spite of the curved outer surfaces of welding spots. To show the potential of high-resolution acoustic imaging technique we used a widefield short-pulse acoustic microscope (see Fig. 2). The method was applied to evaluation of spot-welding joints of two steels sheets 1-2 mm thick of each. In spite of the fact that the top surface of specimen was distributed by welding, high quality acoustic images of the nugget zone were obtained [9]. The C-scan and B-scan images contain well-shaped defects of joints and the confirm power of the method for NDE and QC of spot-welded joints. The combination of the C-scan and the B-scan images in one picture can give a real 3D image of the defect distribution inside the welding zone, which can be also very useful from a technological point of view. The current results of this study show that high-resolution acoustic imaging technique can be successfully applied in spot welding as an effective inspection method to detect any kind of defects, and can be used for manufacturing welding quality control. 699 Fig. 7. C-scan Images of the interface area (depth penetration 1 mm) from the spot welding samples (Ultrasound frequency 50 MHz). Acoustic imaging methods based on acoustic visualization and characterization are extremely promising also for laser welds and rivet joints quality evaluation (see figure 5). This technique can provide total bulk reconstruction of the joint zone, including the topography of the top and bottom faces, the structure of the interface between the sheets, and any expulsions, voids, pores, cracks or other defects in the welding zone. BULK AND SUBSURFACE STRUCTURE ANALYSIS OF ALUMINUM CASTING USING ACOUSTIC IMAGING METHODS The metallurgical structure of aluminum castings (grain structure, inclusions, porosity etc.) is usually inspected with optical and scanning electron microscopy. [10, 11]. These both methods provide information only from the surface of a sample while requiring as-polished or etched metallographic specimens [12]. In a bulk structure study, as a rule, a series of cross sections is required [112]. Through the image processing some important quantitative characteristics of the casting structure may be provided [14]. The main point of this study was to apply the method of acoustic microscopy for the subsurface and non-destructive bulk structure visualization as well as casting quantitative characterization. The service properties of Al-Si-Cu castings depends on their chemical composition, liquid metal treatment and solidification rate. In general, a small, equiaxed grain structure, fine constituents and absence of structural discontinuities produces optimal properties. Consequently, the casting responds better to heat treatment processes. Porosity in aluminum casting can result from excessive amounts of hydrogen (gas porosity) or a lack of feeding (shrinkage porosity) [15, 16]. Gas porosity takes the form of rounded cavities while shrinkage porosity appears as elongated interdendritic cavities. Commercial castings can contain either type or both in combination. The service performance of automotive components, especially during high cycle fatigue, depends on the morphological characteristics of the porosity. These characteristics can be determined using traditional destructive microscopy techniques, however these techniques are costly and time consuming. They do not allow process engineers to make proactive interventions. Consequently, it is essential that quick, non-destructive techniques for the evaluation of internal casting structure be developed that can be utilized in an industrial environment. Some test samples were cut out from different parts of automobile engines. The samples employed in ELSAM study were prepared using traditional optical microscopy techniques. Others had no such ideal surface and were prepared with 700 different surface finishes ranging from rough machining to samples with a mirror-like surface. A few samples were studied with the as-cast rough surface. SPSAM Results The ability to locate the exact position of an object using the acoustic microscopy method is based on the study of the reflections of acoustic waves from the object and the discontinuities inside it [17]. Fig. 8 demonstrates the ability of the acoustic microscopy method to reveal the location of flaws in the casting structure. The figure depicts a collection of acoustic images showing the volume distribution of shrinkage porosity and non-visible cracks inside the sample. It consists of an acoustic image of the machined surface and three other images of the subsurface structure. All of the pictures show high-contrast images of imperfections (the dark spots) in the bulk area of the sample. In Fig. 8a, the C-scan image shows only the machined surface information because the electronic gate is set at the surface of the examining sample. With adjustment of the electronic gate, the volume information can be represented as a set of images with smaller volume information. Fig. 8b to 8d represent volume information from three different layers: between 0.1 to 0.5 mm, 0.5 to 1.0 mm, and 1.0 to 1.5 mm respectively. The acoustic microscope's ability to locate flaws is demonstrated by examining those images with smaller volume information. (a) Surface (d) Depth range 1.0 to 1.5 mm C-scan 1 mm B-scan (c) Depth range 0.5 to 1.0 mm 1 mm (b) Depth range 0.1 to 0.5 mm Fig. 8. Acoustic B- and C-scan images of an aluminum casting sample Each figure, 8b to 8d, shows a couple of results: a C-scan image in which the researcher chooses a particular layer of aluminum casting specimen and a B-scan image taken at the position of flaw where the dark line indicates a corresponding Cscan image. Since the velocity of acoustic wave propagating in the Al-casting is known, by examining the time delay, the location of the flaws can be calculated (in the case of the Fig. 8b: they are about 0.3 mm below the surface). Similar procedures for two different gate positions are depicted in Fig. 8c and 8d. Fig. 8c shows that other flaws are located at about 1.0 mm below the surface; Fig. 8c indicates that yet another flaw is located at about 1.4 mm beneath the surface. Therefore, taken together, the C and B scan images provide information about the exact location of the detected flaws. ELSAM RESULTS The resolution of the acoustic microscope in high frequency renders comparable results to those shown by the light microscope. Furthermore, acoustic microscopy is 701 capable of penetrating optically opaque material. The difference in quantitative results may be attributed to the difference in depths of images. Fig. 9 shows microstructure of a Al-casting alloy with shrinkage porosity and the Cu-rich phase. The ability to focus on a specified depth range (10 µm in this case) allows for better contrast images of Cu-rich phase in acoustic image. Fig. 10 illustrates the eutectic Si structure of the Al-casting alloy. Fig. 10a is obtained using the light microscope; Fig. 10b shows acoustical image of higher magnification, with area corresponding to the region marked as a box on Fig. 10a. The transducer was focused 20 µm deep under the surface that explains why surface scratches, easily noticeable in optical image, are almost invisible in acoustical image. 100 (a) (b) Fig. 9. (a) Light optical micrograph and (b) acoustic micrograph (1.4 GHz lens) of Al-casting alloy polished surface, showing fragments of the shrinkage porosity and Cu-rich phase. (a) (b) Fig. 10. Microstructure of Al-casting alloy, (a) Light optical micrograph, showing relatively well-modified eutectic Si structure, and (b) acoustic micrograph (1.4 GHz lens), showing details of the microstructure from (a). CONCLUSION Main areas to which acoustic imaging may be applied are finished product inspection and the detection of inclusions and discontinuities. Such technique has the potential to provide reliable, rapid and cost effective methods to visualize high contrast smallscale failures and defects at different depths within inspected parts. Provided this technology can adapt to high volume manufacture, it has considerable promise for application to the advance manufacturing quality control inspection. 702 REFERENCES 1. A. Briggs: Acoustic microscopy. Claredon Press, Oxford, 1992. 2. R. Gr. Maev: Scanning acoustic microscopy of polymeric and biological substances. Tutorial Archives of Acoustics, 1988, 13: 13–43. 3. R. G.r Maev: Einsatz der Akustomicroskopie in den Materialwissenschaften. Review of the BRD-USSR bilateral seminar “Microscopy in Material Sciences”, Moscow, 1988, 3542. 4. M. Hoppe: Design and Performance of the Leitz ELSAM High Resolution Acoustic Microscope. Proc. The First Joint Soviet–West Germany International Symposium On Microscope Photometry and Acoustic Microscopy in Science, Moscow, (Ed. M. Hoppe, R. Maev), USSR, September 16–21, 1985. 5. K.I. Maslov: Acoustic Scanning Microscope for Investigation of Subsurface Defects. Acoustical Imaging, V.20, Plenum Press, NY, 274-281, 1993. 6. K. Erikson, A. Hairston, A. Nicoli, J. Stockwell, and T. White, A 128128 ultrasonic transducer array, in: Proc. IEEE Ultrasonics Symp., Vol. 2, IEEE, NY, 1625, 1997. 7. D. H. Turnbull, Two-Dimensional Transducer Arrays for Medical Ultrasonic Imaging, Ph.D. Thesis, University of Toronto 1992. 8. R. Gr. Maev, A. Ptchelintsev and A. Denissov, Acoustical imaging using matrix of piezoelectric transducers for nondestructive evaluation of plastic composites, in: Proc. ICCE, 665-667, ICCE Orlando, 1999. 9. R.Gr. Maev, D.F. Watt, R. Pan, et all, Development of high resolution ultrasonic inspection methods for welding microdefectoscopy, Acoustical Imaging, V.22, Plenum Press, NY, 779-784,1996. 10. Optical Microscopy, G. F. Vander Voort, eds., ASM International, V. 9 1992. 11. Scanning Electron Microscopy, H. E. Exner, eds., ASM International, V. 9 1992. 12. V. A. Phillips: Modern Metallographic Techniques and Their Appplications. Interscience, 1971. 12. R. C. Gifkins: Optical Microscopy of Metals. Elsevier Publishing, NY, 1970. 14. R. J. Lee, W. A. Spitzig, J. F. Kelly, R. M. Fisher: Quantitative Metallography by Computer-Controlled Scanning Electron Microscopy, Pract. Metallogr., 21: 27–41 1984. 15. Aluminum and Aluminum Alloys, J. Davis, eds., ASM International, 1993. 16. G. Powell, S-H, Cheng, C. Mobley: A Fractography Atlas of Casting Alloys. Battelle Press, 1992. 17. J. H. Sokolowski, R. G. Maev, H. T. Lee, E. Y. Maeva, and K. I. Maslov: Analysis of Casting Subsurface Structure Using Acoustic Microscopy, Proc. QNDE, Snowbird, Utah, July 19–24, 1998. 703