Patients and Methods

advertisement

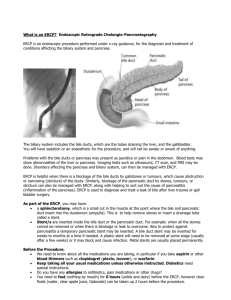

THE ROLE OF ERCP IN THE EVALUATION, DIAGNOSIS AND THERAPY OF BILIARY AND PANCREATIC DISEASES IN CHILDREN Haissam Nourallah, MD, CES; Hussain Issa, MD; Ahmed H. Al-Salem, FRCSI, FICS, FACS The role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for the investigation and treatment of biliary and pancreatic diseases is well established in adults.1 This, however, is not the case in the pediatric age group, because biliary and pancreatic diseases are less common in children. In addition to this problem is the lack of pediatric gastroenterologists who are skilled in performing ERCP in children. Recently, however, and as a result of the routine use of ultrasonography in the evaluation of children with abdominal pain, biliary and pancreatic diseases are being diagnosed more often in children,2 especially in areas where hemolytic diseases which are known to be associated with increased frequency of cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis are common.3-5 The present study describes our experience with ERCP in the evaluation, diagnosis and treatment of pancreatobiliary disorders in children and demonstrates its value in the era of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Patients and Methods Over a four-year period from September 1993 to August 1997, 34 consecutive children less than 18 years old had ERCP as part of their management at our hospital. The records of these patients were reviewed retrospectively for age, gender, indication for ERCP, pre-ERCP investigations, results, complications of ERCP and post-ERCP management. Informed, written consent for ERCP was obtained from the child’s parent. All ERCPs were performed in the Radiology Department. For patients 10 years old and below, ERCP was performed under general anesthesia with nasotracheal intubation. In those older than 10 years, ERCP was done under sedation only. Patients with sickle cell disease were hydrated with intravenous fluids starting the night before the procedure, at a rate of 1½ their maintenance requirements, and blood transfusions were given when necessary to increase their Hb to 10-12 g/dL. From the Departments of Medicine and Surgery, Qatif Central Hospital, Qatif, Saudi Arabia. Address reprint requests and correspondence to Dr. Al-Salem: P.O. Box 18342, Qatif 31911, Saudi Arabia. Accepted for publication 29 November 1998. Received 24 February 1998. With the patients properly sedated, using meperedine (1 mg/kg) and diazepam (0.1-0.2 mg/kg), the Olympus JF1 T20 side-viewing duodenoscope was used in all the patients. After visualization, the ampulla of Vater was cannulated with tapered catheters and the pancreatic and biliary ducts were visualized by fluoroscopy during injection of Hexabrix (320 mg was diluted to 50%). Appropriate radiographs were obtained in all cases. Where indicated, sphincterotomy was performed using 5F sphincterotome (Olympus). Common bile duct stone extraction was performed with basket and balloon catheters. During the procedure, all patients were monitored with pulse oximetry with a cardiorespiratory trolley at the bedside. Results The 34 children who had ERCP at Qatif Central Hospital as part of their management over the four-year study period comprised 20 males and 14 females. Their ages ranged from 5-18 years (mean 14.5 years). Of the 34 patients, 29 (85.3%) had sickle cell disease (SCD). Their mean HbS level was 77.8% (range 66.1-90.7) and their TABLE 1. Indications for ERCP. Indications for ERCP # of patients Obstructive jaundice 22 Pancreatitis 4 Cholangitis 3 Recurrent biliary colic 2 Post-liver injury bile lead 1 Post-laparoscopic cholecystectomy with bile leak 1 Total 34 TABLE 2. Procedures performed during ERCP. Procedure # of patients Endoscopic sphincterotomy only 10 Endoscopic sphincterotomy + stone extraction 9 Endoscopic sphincterotomy + stone extraction + nasobiliary tube drainage 2 Endoscopic sphincterotomy + biliary stent 1 Endoscopic sphincterotomy + mechanical lithotripsy + stone extraction 1 Annals of Saudi Medicine, Vol 19, No 2, 1999 163 NOURALLAH ET AL mean HbF level was 21% (range 7.2-37). The indications for ERCP are shown in Table 1. Obstructive jaundice was the most common indication in 22 patients (64.7%). The mean total bilirubin for those patients with obstructive jaundice was 14.4 mg/dL (range 6.6-36), and their mean alkaline phosphatase was 325.8 IU (range 148-545) (normal, 50-136 IU). In those with obstructive jaundice, pre-ERCP abdominal ultrasound showed dilated CBD with no CBD stones in seven patients, dilated CBD associated with CBD stones in six patients, and normal CBD in nine patients. Gallstones were diagnosed in 15 patients and biliary sludge in two patients. ERCP, on the other hand, showed dilated CBD with no CBD stones in seven patients, two of them with enlarged inflamed papilla suggestive of recent stone passage, dilated CBD and CBD stones in 11, and normal CBD in four patients, one of them with an enlarged inflamed papilla suggestive of recent passage of a stone. Gallstones were diagnosed in 16 patients. While ultrasound was accurate in diagnosing choledocholithiasis in only six of 22 children (27.3%) with obstructive jaundice, ERCP on the other hand diagnosed CBD stones in 11 patients (50%) (Figure 1). In three other patients, an inflamed enlarged papilla suggestive of recent stone passage was visualized. The remaining eight patients did not have CBD stones. Of the 22 children with obstructive jaundice, ultrasound showed CBD dilatation in 13 (59%), while ERCP showed CBD dilation in 18 (81.8%) children. Three other patients had obstructive jaundice and ascending cholangitis. ERCP revealed a dilated CBD with CBD stones in one, CBD dilation and papillary stenosis in another, and was normal in the third patient. Four patients had pancreatitis, and in one of them ERCP showed gallstones only, while in another there was a dilated CBD with no stones but an inflamed enlarged papilla suggestive of recent stone passage. In the third, ERCP revealed gallstones and dilated CBD but no stones. The fourth was a five-year-old child with recurrent pancreatitis. ERCP in this child showed a choledochocele. One patient had a post-LC bile leak. ERCP in this patient revealed retained CBD stones and bile leak from cystic duct stump (Figure 2). Another SCD patient presented with obstructive jaundice following LC. ERCP in this patient showed dilated CBD but no stone or stricture. One of our patients had recurrent biliary colic with a total bilirubin of 1.8 mg/dL and an alkaline phosphatase of 177 IU. An abdominal ultrasound revealed a dilated CBD with biliary sludge. ERCP in this patient showed a normal CBD, normal papilla, normal pancreatic duct, and cholelithiasis, but no choledocholithiasis. This patient subsequently had LC. The other patient with recurrent biliary colic had in addition abnormal liver function test. ERCP in this patient showed normal CBD and gallstones, and he subsequently had LC. ERCP in the patient with postliver injury bile leak showed bile leak from the second order branch of the right hepatic duct, but the CBD was normal. This patient was treated 164 Annals of Saudi Medicine, Vol 19, No 2, 1999 with endoscopic sphincterotomy and biliary stent with eventual sealing of the leak. The different procedures performed during ERCP are shown in Table 2. After the ERCP, none of our patients with SCD developed complications related to SCD or anesthesia. Two of our patients (5.9%) developed mild attacks of post-ERCP pancreatitis which resolved conservatively. Discussion In adults, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has a well-defined role in the diagnosis and management of biliary and pancreatic diseases.1 In the pediatric age group, however, the use of ERCP is limited because biliary and pancreatic diseases are less common in children, and there is a general lack of skilled pediatric gastroenterologists capable of performing ERCP in children. In this study, we were successful in performing ERCP for 34 children. Considering the rarity of biliary and pancreatic diseases in children, our series is not small, and this is because the majority of our patients (85%) had sickle cell disease. Cholelithiasis is known to be common in children with SCD. The prevalence of cholelithiasis in patients with SCD ranges from 17% to 55% and increases with age.5-9 A 19.7% frequency of cholelithiasis has been reported in Saudi children with SCD.4 In children with non-hemolytic gallstones, a frequency of about 7% of choledocholithiasis has been reported.2 This is in comparison with 14% to 30% in SCD patients with gallstones.3,10-12 In a previous study, we reported a frequency of CBD stones of 30% in children with SCD undergoing cholecystectomy,3 and based on this high frequency we recommended routine intraoperative cholangiogram. This may necessitate CBD exploration and open transduodenal sphincterotomy and sphincteroplasty. Considering the high prevalence of cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis in children with SCD, exclusion of CBD stones prior to cholecystectomy is of great importance. This is especially so in the era of LC. Like others, we found ERCP to be useful both in the diagnosis and management of CBD stones prior to LC.13,14 A 97% cannulation success rate in our series is similar to the experience of others.15-17 Although pediatric duodenoscopes are now available, ERCP was performed in our patients without difficulty, using the adult-size viewing duodenoscope under sedation, except in those children aged 10 years or younger, where this was done under general anesthesia to protect against airway compression. The youngest patient in our series was five years old. With the recent advancement in pediatric endoscopes, it is now possible for ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy to be performed in infants.13 ERCP is clearly superior to ultrasound in diagnosing CBD stones, but it cannot be used routinely as it is invasive, costly and not without morbidity. Therefore, dilation of CBD on ultrasound, an elevated alkaline phosphatase, BRIEF REPORT: ROLE OF ERCP pancreatitis and an elevated total bilirubin of more than 5 mg/dL, either singly or in combination, should raise the possibility of CBD stones in these patients. These patients together with those with CBD stones detected on ultrasound should undergo ERCP to confirm and extract CBD stones prior to LC. This combined endoscopic sphincterotomy and stone extraction followed by LC has been reported in adults,18,19 and recently in patients with SCD.14 We found ERCP valuable in the diagnosis and management of CBD stones prior to LC. Eleven of our patients with CBD stones had successful ERCP and stone extraction prior to LC. One of them had mechanical lithotripsy via ERCP, and stone extraction because of the large size of CBD stones, followed by LC. Ten other patients with dilated CBD but no stones had endoscopic sphincterotomy only. This may prove to be useful in the future for these patients, as they are likely to develop recurrent bile duct stones or biliary sludge. This is especially so in the presence of dilated CBD, and since these stones are usually small to start with, they are likely to pass spontaneously in the presence of sphincterotomy. Two of our patients had ERCP following LC to diagnose and treat retained CBD stones. One of them had bile leak from the cystic duct stump following LC. ERCP in this patient showed a retained CBD stone which was extracted with subsequent closure of the bile leak. In the other patient, ERCP was normal and jaundice in this patient was secondary to hepatic crisis. In those with pancreatitis, ERCP was useful in diagnosing the disease. In three of them, there were gallstones, and in two the CBD was dilated with an enlarged inflamed papilla suggestive of recent stone passage. The fourth patient with recurrent pancreatitis had choledochocele. ERCP in the child with post-liver injury bile leak proved useful both for diagnosis and treatment. Recently the indications for ERCP in children have been extended to include the investigations of a variety of clinical conditions, including biliary atresia,20 choledochal cyst,21 recurrent pancreatitis,22 cholestatic jaundice,23 traumatic pancreatic duct disruption,24 and the investigation of bile leak following liver transplant.25 In our series, two patients developed post-ERCP mild pancreatitis, which is comparable to the 10% complication rate of endoscopic sphincterotomy reported both in children and in adults.17,26,27 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. References 27. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Cotton PB. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography. Gut 1977;18:316-41. Holcomb GW Jr, O’Neil JA Jr, Holcomb GW III. Cholecystitis, cholelithiasis and common duct stenosis in children and adolescents. Ann Surg 1980;191:626-35. Al-Salem AH, Nangalia R, Kolar K, et al. Cholecystectomy in children with sickle cell disease: perioperative management. Pediatr Surg Int 1995;10:472-4. Al-Salem AH, Qaisaruddin S, Al-Dabbous I, et al. Cholelithiasis in children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Surg Int 1996;11:471-3. Barrett-Connor E. Cholelithiasis in sickle cell anemia. Am J Med 1968;45:889:98. Karayalcin G, Hassani N, Abrams M, Lanzkowsky PH. Cholelithiasis in children with sickle cell disease. Am J Dis Child 1979;133:306-7. Phillips JC, Gerald BE. The incidence of cholelithiasis in sickle cell disease. Am J Roetgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1971;113:27-8. Rennels MB, Dunne MG, Grossman NJ, Schuntz AD. Cholelithiasis in patients with major sickle cell hemoglobinopathies. Am J Dis Child 1984;138:66-7. Sarnaik S, Slovis T, Corbett DP, et al. Incidence of cholelithiasis in sickle cell anemia using the ultrasound Gray Scale technique. J Pediatr 1980;96:1005-8. Cameron JL, Maddrey WC, Zuidema GD. Biliary tract disease in sickle cell anemia: surgical considerations. Ann Surg 1971;174:70210. Schubert TT. Hepatobiliary system in sickle cell disease. Gastroenterology 1986;90:2013-21. Ware RE, Schultz WH, Filston HC, et al. Diagnosis and management of common bile duct stones in patients with sickle hemoglobinopathies. J Pediatr Surg 1992;27:572-5. Guelrud N, Rincones VZ, Jaen D, et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy and laparoscopic cholecystectomy in a jaundiced infant. Gastrointest Endosc 1994;40:99-102. Gholson CF, Grier JF, Ibach MB, et al. Sequential endoscopic/ laparoscopic management of sickle cell hemoglobinopathy-associated cholelithiasis and suspected choledocholithiasis. Southern Med J 1995;88:1131-5. Allendorph M, Werlin SL, Green JE, et al. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in children. J Pediatr 1987;110:206-11. Buckley A, Connon JJ. The role of ERCP in children and adolescents. Gastrointest Endosc 1990;36:369-72. Guelrud M, Mendoza S, Jaen D, Plaz J, Machuca J, Torres P. ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy in infants and children with jaundice due to common bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc 1992;38:450-3. Duensing RA, Williams RA, Collins JC, Wilson SE. Managing choledocholithiasis in the laparoscopic era. Am J Surg 1995;170:61923. Aliperti G, Edmundowicz SA, Soper NJ. Combined endoscopic sphincterotomy and laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with choledocholithiasis and cholecystolithiasis. Ann Intern Med 1991;115: 783-4. Guelrud M, Jaen D, Mendoza S, et al. ERCP in the diagnosis of extrahepatic biliary atresia. Gastrointest Endosc 1991;37:522-6. Thatcher BS, Sivak MV, Hermann RE, Esselstyn CB. ERCP in evaluation and diagnosis of choledocal cyst: report of five cases. Gastrointest Endosc 1986;32:27-31. Guelrud M, Mujica C, Jaen D, Plaz J, Arias J. The role of ERCP in the diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic recurrent pancreatitis in children and adolescents. Gastrointest Endosc 1994;40:428-36. Derky HHF, Hibregtse K, Taminian JAJM. The role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in cholestatic infants. Endoscopy 1994;26:724-8. Hall RI, Lavelle MI, Venables CW. Use of ERCP to identify the site of traumatic injuries of the main pancreatic duct in children. Br J Surg 1986;73:411-23. Starzl TE, Dominguez R, Young LW, et al. Pediatric liver transplantation. II. Diagnostic imaging in post-operative management. Radiology 1985;157:339-44. Brown KO, Goldschmiedt M. Endoscopic therapy of biliary and pancreatic disorders in children. Endoscopy 1994;26:719-23. Freeman M, Nelson DB, Sherman S, et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med 1996;335:909-18. Annals of Saudi Medicine, Vol 19, No 2, 1999 165