Solutions ED overcrowding

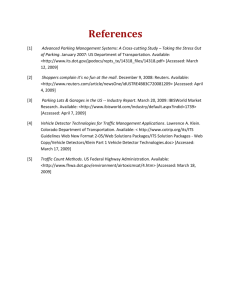

advertisement