Possible Responses to the Open Question Argument

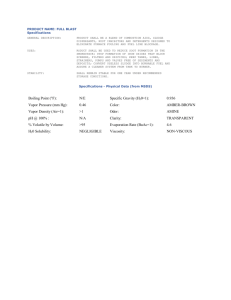

advertisement

Possible Responses to the Open Question Argument The argument claims that we can always ask in a meaningful way if a particular natural property really is good. For example, we can ask, ‘Is pleasure good?’, or ,’Is happiness good?’, and these questions seem reasonable, suggesting that these natural properties are not really identical with moral ones. If they were identical then we would find the question ‘closed’ – not in need of an answer. Here are two responses which have been put to the open question argument. Do you find them convincing? Why (not)? 1 A question may have the appearance of being legitimate, in the sense of standing in need of an answer, but it actually has an objectively correct answer of which many of us are not consciously aware. It is possible that we act in ways which suggest we all think happiness is good, but we can’t necessarily understand this as a universally true statement. One analogy is with grammar. Is the following question one which has an obvious answer? Is it the case that a gerund must always be preceded by the possessive adjective? May I say ‘This is me being difficult’, or must I say ‘This is my being difficult.’? 2 Another defence of naturalistic reductionism in the face of Moore’s open question argument is that we can believe in the reducibility of moral properties to natural ones, but we needn’t think this will be reflected in our use of language. For example, a competent user of the language can know ‘water = H20, but it is still a meaningful question to ask if water is the same as H20. If a competent user of English can doubt that water = H20, then why can’t she doubt that pleasure is good. In each case the existence of doubt fails to undermine the claim that her there is a correct answer.