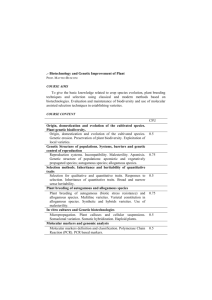

Intellectual Property, Traditional Knowledge and Genetic

advertisement