IMPACT OF CHLORINE ON THE DISSOLVED ORGANIC MATTER

advertisement

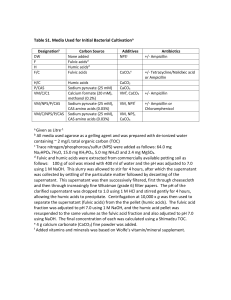

IMPACT OF CHLORINE ON THE DISSOLVED ORGANIC MATTER : SUVA, REPARTITION OF HYDROPHOBIC AND HYDROPHILIC SUBSTANCES, FLUORESCENCE, PYROLYSIS AND DESINFECTION BY PRODUCTS (DBPs) D. RECKHOW, B. MOUSSET, J. McCOLLAN and Y. Department of Civil Engineering, University of Massachusetts, at Amherst Amherst, MA 01003 Abstract C:\DAR\RES\Epa2\Mousset\pap3\redaction.doc Keywords Natural organic matter, Raw and chlorinated waters, Repartition hydrophobic and hydrophilic substances, SUVA, pyrolysis and DBPs. Introduction The natural organic matter (NOM) was characterized by non-specific parameters such as COT, DOC, and UV absorbance, by reactivity with coagulant and oxidant and most recently by biodegradable organic matter (BDOC), by sophistical analytical such as 13C and 15N RMN, fluorescence and pyrolysis. However, those sophistical techniques are easily applicable to pure substances. Their applicability to NOM is more uncertain, because the salts could be disturbed the results and need a high quantity of sample. So it’s necessary to extract, to concentrate and to purify the NOM. Different isolation procedures have been used during the last decades, including adsorption into XAD, anionic and cationic resins, filtration with membranes (ultrafiltration, nanofiltration and reverse osmosis), and rotary evaporation. But the basis of the most widely used procedures is proposed by THURMAN and MALCOLM (1981) or by LEENHEER (1981). The organic natural matter separated based on charge and hydrophobic properties. The fractionation scheme divided the organic matter into two major categories : hydrophobic and hydrophilic and at least three subcategories : acids, bases and neutrals. The ratio of UV absorbance/DOC, named SUVA, is very useful and used by many people because it represents the aromaticity of the organic matter and can correlate with other parameters, such as the chlorine demand, organohalogenated compounds (TOX) and trihalomethanes (THM). The organic matter reacts with ozone and chlorine to form disinfection by-products (DBPs) such as THM and haloacetic acids with chlorine and aldehydes and ketoacids with ozone. The fluorescence is useful because the maximum wavelength increase with the molecular weight shown by BELIN et al. (1993) and COBLE (1996) used it to characterize the water of different origins. The pyrolysis is a very promising method that can already be used to estimate the overall composition of the organic matrix of waters. This method is a thermal degradation method and fragments the organic matter in reproducible and significant products, which analyzed by gas chromatography. Those fragments could be compared with model compounds and can be related to the structure of the undegraded products such as polysaccharides, proteins, lignin, and aromatic and polyhydroxyaromatic compounds. The pyrolysis is a semi-quantitative method. However the fragments could be shown correlation between the results of the pyrolysis and the results obtained with other quantitative methods (MARTIN, 1995 and LABOUYRIE-ROUILLER, 1997). Examples, the relation between the aminoacids and the structure derived by proteins, the polysaccharides and the sugars or the polyhydroxyaromatic structures and the UV absorbance characterization of the aromatic groups. And more, the fragments obtained by pyrolysis show information on the origin of the water, aquagenic or pedogenic organic mater than unlined BRUCHET (1990) and BIBER et al. (1996). But the pyrolysis and pyrolysis/methylation have been used together, because they present each other some limitations. The aim of the present work was to evaluate the impact of chlorine on different parameters : DOC, UV absorbance, SUVA, fluorescence repartition hydrophobic and hydrophilic substances and characterization of the fractions with SUVA, fluorescence and reactivity with chlorine (diminution of UV absorbance at 272 nm, chlorine demand, TOX, THM and HAA). Materials and Methods DOC measurement Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) was measured using a Shimadzu Model TOC-500A with ASI-5000A autosampler, calibrated with a potassium hydrogen phthalate standard (C8H5O4K) solution containing 2, 5 and 10 mg C l-1. For each sample, a minimum of triplicate measurements was made. UV absorbance measurement UV absorbance of all fractions was measured at 254 nm in one or five path length quartz cell using a spectrophotometer (Lambda 3A UV/Vis spectrophotometer, Perking Elmer corporation, Norwalk CT). Extraction and fractionation of NOM NOM fractions, used in this study, were according to the procedure developed by LEENHEER and NOYES (1984), RECKHOW et al. (1993) and THURMAN and MALCOLM (1981). The NOM was filtered on tow filters : the first is type DH rated the retain 98% of particles 25 m in diameter and the second filter unit contains filter tube (type AAH) rated to retain 98% of particles 0.3 m in diameter. The extraction system consisted of two steps. The first one, around 200 liters of water was filtered at pH neutral through the three resin columns of 2 liters (XAD-8, MSC-1 and A-7) connected in series at the rate of 6 liters per hour (figure 1). NaOH 1 N and Milli-Q water 1 - WHoA 2 - HoB 3 - HoN Filters x D H A A H 25 m 0.3 m Water neutral pH NaOH 10 N and Milli-Q water X A D 8 1 - NaOH 0.1 M and Milli-Q water 2 - HCl 0.1 M and 0.01 M 3 - Methanol M S C 1 HyB A 7 HS pH 1 HyA uHyA HyN HA FA HyA uHyA (HyN : hydrophilic neutral, HyB : hydrophilic base, HyA : hydrophilic acid, HoN : hydrophobic neutral, HoB : hydrophobic base, WHoA : weak hydrophobic acid, HS : humic substances, FA : fulvic acid, HA : humic acid, uHyA : ultra hydrophilic acid) Figure 1 : Fractionation procedure The organic natural matter separated based on charge and hydrophobic properties. The fractionation scheme divided the organic matter into two major categories : hydrophobic and hydrophilic and at least three subcategories : acids, bases and neutrals. The second step corresponds of an elution at 0.85 l/h of fractions : the hydrophilic base (HyB), the hydrophobic base (HoB) and the weak hydrophobic acid (WHoA) were eluted by NaOH or HCl in XAD-8 and MSC-1 resins. The hydrophobic neutral (HoN) were extracted in XAD-8 by methanol in soxhlet. On resin A-7 were eluted together, fulvic acid (FA) and humic acid (HA) corresponded of humic substances (SH), hydrophilic acid (HyA) and ultra hydrophilic acid (uHyA). The fractions, that have a DOC more than 200 mg C/l, were acidified at pH 1 for the separation of humic acids that precipitated. The humic acids were separated by centrifugation (30 min, 500 rpm). The salts were staying in the suspended fraction. So all of the humic acids were recovered and the procedure avoids the precipitation of this fraction on the H+ exchange resin. This problem of the precipitation was unlighted by SUN et al. (1995). The procedure which was represented in figure 2, consisted by the separation of fulvic, hydrophilic and ultra hydrophilic acids at pH 2 on 0.5 liter of each resins XAD-8 and XAD-4 in series ; than by the elution and finely by the purification. The rates of filtration are 0.8 l/h in XAD-8 and 0.4 l/h in XAD-4 and the volume is 12 liters with a DOC < 10 mg C/l in accordance with the procedure of MALCOLM et al. (1993). HyA FA M S C 1 x 3- NaOH 0.1 M X A D 8 x X A D 4 FA without salts uHyA 1- FA + HyA + uHyA pH=2 1- HyA + uHyA pH=2 2- Milli-Q water 2- Milli-Q water M S C 1 3- NaOH 0.1 M NaOH pallet HyA without salts (FA : fulvic acid, HyA : hydrophilic acid, uHyA : ultra hydrophilic acid) Figure 2 : Concentration and purification of fulvic and hydrophilic acids The ultra hydrophilic acid and the hydrophilic neutral fractions were concentrated by rotary evaporation at 40C. The fulvic and hydrophilic acids could be drying. Fluorescence measurement The fluorescence spectra of all extracts were recorded with a spectrofluorophotometer model RF-540 (Shimadzu) equipped with a monochromator both on excitation and emission (Off-plane concave diffraction, aperture : f/2.6). The signal of photons was detected by a photometric photomultipliplier R452-01. The first sample was introduced in a 1 cm square cell at the temperature of the room (20 degree C) and the wavelength of excitation was set at 313 nm as mentioned by E WALD et al. (1983). Pyrolysis gas chromatography/mass spectrometry GC/MS The method of pyrolysis alone used was similar to the one published by BRUCHET et al. (1990). The fractions were concentrated by different methods reported upstairs. The sample must be have got a DOC more than 100 mg C/l. A few milliliters were transformed, under a nitrogen stream, to a solid fraction. Then the pyrolysis GC/MS experiments were run on around 50 mg of sample deposited into quartz tube, which was inserted into a filament pyrolyzer. The salts were lost during the evaporation on the wall of the tube. ALCANIZ et al. (1989) were demonstrated that the usual salts, that found in the water, could be reduced the intensity of response without changed the pyrogram. For the pyrolysis/methylation, one step of methylation was added before pyrolysis. A derivatizing reagent used was the tetramethylammonium hydroxide (25 wt % solution in water) noted TMAH. This method is described in detail elsewhere (CHALLINOR, 1989, SAIZ-JIMMENEZ et al., 1993 ; De LEEUW and BAAS, 1993 ; DEL RIO and HATCHER, 1996) and is briefly explained here. Approximately 5 l of the TMAH was placed with the sample in the quartz tube. The all was inserted into a filament pyrolyzer. The temperature programmation of pyrolysis was 200C (1 s) to 700C (10 s) at the rate of 20C/ms with a CDS 1500 pyroprobe 2000. At this temperature, the organic matter produced different fragments separated on a 30 cm length DB WAX capillary column by Hewlett Packard 5890A gas chromatography flushed with helium gas. The oven programmation was from 25 to 220C at the rate of 3C/min and the identification was made by a Hewlett Packard 5988A mass spectrometer operated at 70 ev and scanned from 20 to 400 amu at 1 scan/s. The semi-quantitative interpretation of pyrograms of the fractions was followed as BRUCHET et al. (1990) except that the sums were not multiplied by a corrective factor. An other fragment : the aromatics were added at this list as LABOUYRIE-ROUILLER (1997). And the carboxylic acid methyl ester comes from fatty acids what represents an other group. Some standards (benzene, acetone, 2,3 dimethyl naphthalene, 2 methyl naphthalene, 1 methyl naphthalene, naphthalene, phenol, pyridine, toluene, 2,3,5 trimethyl naphthalene, o xylene, m xylene and p xylene) were injected directly in the GC/MS to confirm the retention time. Results and discussions Presentation of the sampling waters This study was realized on two different waters sampling on May 26 1998. The first water was sampling in the Wachusett reservoir and the second one was collected in the same place after chlorination. The two waters were filtered on 25 and 0.3 m. The DOC, UV absorbance, SUVA, fluorescence and the elimination of DOC and UV absorbance were presented in the table . Table : DOC, UV absorbance (UV abs), SUVA and fluorescence (maximum emission wavelength of peak C, max) of the chlorinated and raw water and the elimination of DOC and UV absorbance by the chlorine Water DOC Raw Chlorinated (mg C/l) 2.85 2.59 UV Abs -1 (cm ) 0.07 0.0496 max SUVA -1 -1 (m l mg C) 2.56 1.91 Elimination (%) (nm) 427 412 DOC 9 UV Abs 29 The better elimination of the UV absorbance is in accordance with the oxidation by chlorine as the ozone and with the lowest SUVA of chlorinated water. The maximum emission wavelength of peak C was greater for the raw water than the chlorinated water. So the chlorine moved the maximum emission wavelength of peak C toward the smaller maximum emission wavelength. That means under the results of BELIN et al. (1993) that the chlorine broke some links and reduced the apparent molecular weigh. NOM recovery measurements Two filtration of around 200 l were made follow the protocol describe just more height. those volumes correspond in volume where an augmentation of the UV absorbance was seen. The NOM recoveries shown on the table 3, can be estimated, a various stages of a procedure, by measurements of the DOC and of UV absorbance change in the top and in the end of each column. The determination of the percent recoveries is comparing the quantities of carbon or UV absorbance of NOM filtered with the quantities of carbon or UV absorbance of the NOM fractions that adsorbed on the different columns. DOC or UV absorbance and the volume measurements determined the quantities. Table : Organic carbon and UV absorbance recoveries of Wachusett water using filtration and column adsorption system (LEENHEER and NOYES, 1984) Fractions adsorbed Raw Water XAD-8 MSC1 A7 Quantity of organic matter (mg C)* filtered adsorbed 55 13 362 131 29 396 Organic Quantity of UV Abs carbon (cm-1)** recovery (%) filtered adsorbed 239 223 102 1.5 0.6 12.1 1.4 0.6 10.9 UV Abs recovery (%) 94.5 100 90 Chlorinated Water Bilan*** 591 690 115 15.2 13.9 91.5 XAD-8 MSC1 A7 30 23 375 89 29 357 291 125 95 0.7 0.6 8.2 0.75 0.7 8 108 122 97 Bilan*** 545 591 109 10.4 10.3 (* +\- 10 mg C/l, ** +\- 0.08 cm-1, *** all fractions with hydrophilic neutrals) 99 This extraction procedure of the organic matter could be to extract the totality of the DOC and of the UV absorbance of each water. The values were 115% and 109% for DOC and of 91.5 and 99 for UV absorbance. Those results were acceptable in view the error made. Repartition of hydrophobic and hydrophilic fractions The protocol could be split the water into neigh fractions : fulvic acids (FA), weak hydrophobic acids (WhoA), humic acids (HA), hydrophobic neutral (HoN), hydrophobic 4.3% HyB 5.3% UHyA 22.9% HyN 32.8% FA 7.2% HyN 11.2% HyA 4.2% HyB 0.3% HoB 0.5% HoN 8.7% UHyA 53.1% FA 8.8% HA 9.3% HyA 17% WHoA 0.5% HoB 0.9% HoN 9.3% WHoA 3.7% HA DOC distribution UV absorbance distribution Raw water 8.5% HyN 19.7% HyN 6.8% HyB 33.4% FA 5.6% UHyA 4.9% HyB 15.1% HyA 12.3% UHyA 11.1% WHoA 13.5% HyA 1.1% HA 0.4% HoB 3.3% HoN 0.3% HoB 1.9% HoN 2% HA 54.7% FA 5.1% WHoA UV absorbance distribution DOC distribution Chlorinated water Figure 4 : DOC and UV absorbance repartition of hydrophobic and hydrophilic substances (FA : fulvic acid, WHoA : weak hydrophobic acid, HA : humic acid, HoN : hydrophobic neutral, HoB : hydrophobic base, HyA : hydrophilic acid, UHyA : ultra hydrophilic acid, HyN : hydrophilic neutral, HyB : hydrophilic base) bases (HoB), hydrophilic acids (HyA), ultra hydrophilic acids (UHyA), hydrophilic neutrals (HyN), hydrophilic bases (HyB). The figure 4 presents the DOC and the UV absorbance distribution among the fractions. As generally mentioned in the literature (THURMAN, 1985, CROUE et al. 1993, MARTIN, 1995), the DOC was split between the hydrophobic and hydrophilic fractions. The hydrophobic fraction (55 and 50% of DOC respectively for the raw water and the chlorinated water) was in the same proportion than the hydrophilic fraction (45 and 50% of UV absorbance respectively for the raw water and the chlorinated water). But the hydrophobic fractions represent the most fraction of UV absorbance (72% for raw water and 64% for chlorinated water). Those results were in accordance with other researchers (MALCOLM and MAC CARTHY, 1992, LEENHEER and HUFFMAN, 1979 and CROUE et al., 1993). No change of the proportion between the fulvic acid of raw water and chlorinated water. But if the totality of the hydrophobic substances was considered. The chlorine permitted to decrease the proportion of the hydrophobic substances : the DOC hydrophobic substances decreased of 5% (55% for the raw water minus 50% of the chlorinated water) and the UV absorbance reduced of 8% (72% for the raw water minus 64% of the chlorinated water). It could explain that the SUVA of the raw water are greater than the one of the chlorinated water with the best elimination of the hydrophobic substances that more absorbed in UV than the hydrophilic substances. The fulvic acid represents the most fraction of DOC (32.8% for the raw water and 33.4% for the chlorinated water) and UV absorbance (53.1% for the raw water and 54.7% for the chlorinated water) followed by the weak hydrophobic acid, the hydrophilic neutral, the ultra hydrophilic acid, the hydrophilic acid and the hydrophilic base. The hydrophobic acid, humic acid and hydrophobic neutral were little proportion (< 4% of DOC) as underline LEENHEER (1981). SUVA (UV Absorbance/DOC) This measurement was represented the aromaticity of the organic mater. The results were listed in the table . Table 4 : SUVA of the fractions of the raw and chlorinated waters SUVA (m-1 l mg-1 C) Sample FA Raw Water Water Chlorinated 2.52 2.40 WHoA 1.02 0.82 HA 5.00 3.20 HoN 1.08 0.96 HoB 1.96 2.82 HyA 1.96 0.86 uHyA 1.80 0.89 HyN 0.62 0.76 HyB 2.00 2.50 (FA : fulvic acid, WHoA : weak hydrophobic acid, HoN : hydrophobic neutral, HoB : hydrophobic base, HA : humic acid, HyA : hydrophilic acid, uHyA : ultra hydrophilic acid, HyN : hydrophilic neutral, HyB : hydrophilic base) This table clearly demonstrates that the humic acid (HA) is more aromatic in nature than other fractions similar results were publish by AIKEN et al. (1988) and MARTIN (1995). The decrease order is the follow : - raw water HA > FA > HyB = HyA = HoB = uHyA > HoN = WHoA > HyN - chlorinated water HA > HoB > HyB > FA > uHyA = HyA = HyN = WHoA = HoN. (FA : fulvic acid, WHoA : weak hydrophobic acid, HoN : hydrophobic neutral, HoB : hydrophobic base, HA : humic acid, HyA : hydrophilic acid, uHyA : ultra hydrophilic acid, HyN : hydrophilic neutral, HyB : hydrophilic base) The order of each water was different. For the raw water, the SUVA of the hydrophilic base, the hydrophobic base, the hydrophilic acid and the ultra hydrophilic acid was the same order, 2 m-1 l mg-1 C. For the chlorinated water, the SUVA of the ultra hydrophilic acid, the hydrophobic neutral, the hydrophilic acid, the hydrophilic neutral and the weak hydrophobic acid was the same order equal to 0.9 m-1 l mg-1 C. Globally, almost all the fractions of the chlorinated water presented a smaller SUVA than the SUVA of raw water fractions, in accordance of the better elimination of the UV absorbance. The chlorine no change the SUVA of the hydrophobic neutral, hydrophobic base and hydrophilic base and a little SUVA of the hydrophilic neutral, fulvic acid and weak hydrophobic acid. The most fractions that the SUVA decreased were humic acid, ultra hydrophilic acid and hydrophilic acid. Fluorescence maximum wavelength emission (peak C) The chlorine is a oxidant and eliminate preferentially the UV absorbance to compare with the DOC. Only the modification of the maximum emission wavelength of peak C was measured because the peak C represents the humic substances As COBLE (1996) mentioned and because BELIN et al. (1993) unlighted that higher was the emission wavelength maxima (excitation was 313nm) higher was the molecular weight. So, for the peak C, the emission wavelength maxima could be correlated with the molecular weight of organic matter. The fractions and the raw water have got an each band profile between 360 and 550 nm emission for 313 nm excitation. All spectra exhibit distinct emission maxima showed on the table . Table : Fluorescence emission maxima (max) of the different extracts and the raw water of the three waters FA WHoA HoN HoB HA HyA UHyA HyN HyB RW 427 425 398 426 455 413 420 402 398 RT 415 402 422 380 444 421 423 393 396 (RW : raw water, RT : chlorinated water, FA : fulvic acid, WHoA : weak hydrophobic acid, HoN : hydrophobic neutral, HoB : hydrophobic base, HA : humic acid, HyA : hydrophilic acid, UHyA : ultra hydrophilic acid, HyN : hydrophilic neutral, HyB : hydrophilic base) The humic acid gave a maxima emission located in the longest wavelength that was 455 nm for raw water and 444 nm for chlorinated water. Thus the molecular weight for humic acid was bigger than other fractions in accordance with the results of the literature. For all fractions, the decrease order is the follow : - raw water AH > FA = HoB = WhoA > UHyA > HyA > HyN > HoN = HyB - chlorinated water AH > uHyA = HoN = HyA > FA > WhoA = HyB = HyN > HoB. (FA : fulvic acid, WHoA : weak hydrophobic acid, HoN : hydrophobic neutral, HoB : hydrophobic base, HA : humic acid, HyA : hydrophilic acid, UHyA : ultra hydrophilic acid, HyN : hydrophilic neutral, HyB : hydrophilic base) The order of the raw water is different than the one of the chlorinated water. Globally, all the fractions became from chlorinated water except the hydrophobic neutral, hydrophilic acid and the ultra hydrophilic acid, have got a fluorescence emission maxima wavelength less than the fractions of raw water. So during the chlorination, the compounds with the biggest molecular weight were eliminated in many fractions. Results obtained with the pyrolysis gas chromatography mass spectrometry (PY GC MS) and pyrolysis/methylation of the fulvic acids The pyrochromatograms of the pyrolysis are presented on the figures 12 and 13. And the fingerprint of the pyrolysis methylation are showed in the figures et . The major part of the fragments was the first peak with CO2, H2S, CO. It represents between 60% for the fulvic acid of the raw water and 40% of the fulvic acid of the chlorinated water. Any chlorinated compounds were found in the chlorinated water except the chloroform. When the compounds were burnt, the chlorine was released. The main fragments were found in the fulvic acid of the raw and chlorinated waters : benzene, p, m and o xylene, phenol, toluene, acetic acid, derived benzene, derived naphthalene and derived phenol. Principally the aromatic compounds represent those fulvic acids. The source of the aromatic signature was probably due to an input of aromatic compounds with the snow melting. The fulvic acid origin was more pedogenic (compounds represented by derived benzene and naphthalene) than aquagenic. The acetic acid, the phenol and the toluene were the fragments typically associated with biological signature. The biologic activity was just started. Those fulvic acids contain a little proportion of polysaccharides with the peak of derived cyclopentenone, of furan and of indene. The small proportion of polysaccharides is in accordance with the small activity algae in beginning of the spring. And, any amino sugar was included in the structure. Maybe, the activity of microorganisms was just started and the production of the amino sugar is to small to detect them in GC/MS. With the pyrolysis/methylation, the fulvic acid of the raw water presents a butanoic acid methyl ester peak that was not in the fulvic acid of the chlorinated water. And, in the fulvic acid of the chlorinated water, the fatty acids were represented with a lot of derived benzoic acid methyl ester that can be explain the 73.5% of the sum of the aromatic + polyhydroxy aromatic fragments greater than the sum of the raw water fulvic acid. In the fulvic acid of the chlorinated water, the methoxy phenol, benzene and pentane were absented. To ignore the percent of the small molecular fragments, seven classes of compounds (polysaccharides, proteins, amino sugars, polyhydroxy aromatic, aromatic nonsubstituted fragments, unknown origin and fatty acids) were regrouped in the table 11. Table 12 : Different classes of pyrolysis fragments of the fulvic acids of raw and chlorinated waters FA RW no TMAH PHA % Ar % Pr % Ps % Fatty A % AS % u% 14 26.5 35.4 21.4 15.5 4.6 12.8 7.1 4.3 34.9 0 0 18 5.5 WT no 34 39.2 13 11.2 0 0 2.6 TMAH 2 48.4 20.2 7.4 19.1 0 2.9 (FA : fulvic acid, RW : raw water, WT : chlorinated water, Ps : polysaccharides, Pr : proteins, As : amino sugars, PHA : polyhydroxy aromatic fragments, Ar : aromatic non substituted fragments, u : unknown origin) The classes of fragments were not very different for each fulvic acid. The fulvic acids were presented a rich aromatic and polyhydroxy aromatic structure in accordance with the important relative UV absorbance, 49.4% of aromatic and polyhydroxy aromatic fragments for the fulvic acid of the raw water and 73.2% for the fulvic acid of the chlorinated water. For the fulvic acid of the chlorinated water, maybe it better to consider the aromatic and polyhydroxy aromatic fragments of the pyrolysis/methylation : 50.2%. GOBBELS et al. (1990) showed that the defonctionalised fatty acids could be conduct to the formation of aromatic fragments. Note that the fulvic acid of raw water have more unknown fragments than the fulvic acid of the chlorinated water. That could explain by the greater proportion of fatty acid of the fulvic acid of the raw water. With the pyrolysis alone, the fatty acids produced some alkanes and alkenes (HARTGERS et al., 1995) that were considered as unknown fragments. A low level of the proteins and the polysaccharides was found for those fulvic acids of the two waters. Conclusions During the chlorination, the elimination of UV absorbance is better than one of DOC in accordance with the preferentially elimination of the hydrophobic substances. The fluorescence is useful parameter to compare the water and the fractions of the raw and chlorinated waters. The fluorescence brings other information than the SUVA. The fractions that shown modifications of the maximum emission wavelength were not the same fractions than the SUVA change. But the most fractions changed were the humic, fulvic and weak hydrophobic acids together the SUVA and the maximum emission wavelength. For the hydrophobic neutral, hydrophilic acid and the ultra hydrophilic acid only the SUVA was changed and for hydrophobic base and hydrophilic neutral only the maximum emission wavelength was modified. This result explains that those two parameters didn’t correlate. For the different fragments of the pyrolysis or the pyrolysis/methylation, the results of the fulvic acids of the raw and chlorinated waters were different. References Aiken G.R., 1988, A CRITICAL EVALUATION OF THE USE OF MACROPOROUS RESINS FOR THE ISOLATION OF AQUATIC HUMIC SUBSTANCES, “In Humic Substances and their Role in the Environment”, Frimmel F.H. and Christman R.F. Ed, 15-28. Alcaniz J., J. Romera, L. Comellas, R. Munne and A. Puigbo, 1989, EFFECTS OF SOME MINERAL MATRICES ON FLASH PYROLYSIS-GC OF SOIL HUMIC SUBSTANCES, Sci. Total Environ., 81/82, 81-90. Belin C, C. Quellec, M. Lamotte, M. Ewald and P. Simon, 1993, CHARACTERIZATION BY FLUORESCENCE OF THE DISSOLVED ORGANIC MATTER IN NATURAL WATER. APPLICATION TO FRACTIONS OBTAINED BY TANGENTIAL ULTRAFILTRATION AND XAD RESIN ISOLATION, Environ. Technol., 14, 1131-1144. Biber M.V., F.O. Gulacar and J. Buffle, 1996, SEASONAL VARIATIONS IN PRINCIPAL GROUPS OF ORGANIC MATTER IN A EUTROPHIC LAKE USING PYROLYSIS/GC/MS, Environ. Sci. Technol., 30, 3501-3507. Bruchet A., C. Rousseau and J. Mallevialle, 1990, PYROLYSIS-GC-MS FOR INVESTIGATING HIGHMOLECULAR-WEIGHT THM PRECURSORS AND OTHER REFRACTORY ORGANICS, J.AWWA., september, 66-74. Challinor, J.M., 1989, PYROLYSIS-DERIVATISATION-GAS CHROMATOGRAPHY TECHNIQUE FOR THE STRUCTURAL ELUCIDATION OF SOME SYNTHETIC POLYMERS, Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis, 16, 4, 323-333. Coble G.P., 1996, CHARACTERIZATION OF MARINE AND TERRESTRIAL DOM IN SEAWATER USING EXCITATION-EMISSION MATRIX SECTROSCOPY, Marine Chemistry, 51, 325-346. Croue J.P., B. Martin, P. Simon et B. Legube, 1993, LES MATIÈRES HYDROPHOBES ET HYDROPHILES DES EAUX DE RETENUE : EXTRACTION, CARACTÉRISATION ET QUANTIFICATION, Water Supply, 11, 51-62. De Leeuw J.W. and M. Baas, 1993, THE BEHAVIOUR OF ESTERS IN THE PRESENCE OF TETRAMETHYLAMMONIUM SALTS AT ELEVATED TEMPERATURES; FLASH PYROLYSIS OR FLASH CHEMOLYSIS ?, J. Analytical Applied Pyrolysis, 26, 175-184. Del Rio J.C. and P.G. Hatcher, 1996, STRUCTURAL CHARACTERIZATION OF HUMIC SUBSTANCES USING THERMOCHEMOLYSIS WITH TETRAMETHYLAMMONIUM HYDROXIDE, “Humic and fulvic acids, Isolation, structure and environmental role”, Gaffney J.G., N.A. Marley and S.B. Clark Editor, ACS Symposium series 651, American Chemical Society, Wachington DC, Chapter 6, 78-95. Ewald M, C Belin, P Berger and J.H. Weber, 1983, CORRECTED FLUORESCENCE SPECTRA OF FULVIC ACIDS ISOLATED FROM SOIL AND WATER, Environ. Sci. Technol., 17, 501-504. Gobbels F-J. and W. Puttmann, 1997, STRUCTURAL INVESTIGATION OF ISOLATED AQUATIC FULVIC AND HUMIC ACIDS IN SEEPAGE WATER OF WASTE DEPOSITS BY PYROLYSIS-GAS CHROMATOGRAPHY/MASS SPECTROMETRY, Wat. Res., 31, 7, 1609-1618. Hartgers W.A., J.S. Sinninghe Damste and J.W. De Leeuw, 1995, CURIE-POINT PYROLYSIS OF SODIUM SALTS OF FUNCTIONALIZED FATTY ACIDS, Journal Analytical Applied Pyrolysis, 34, 191-217. Labouyrie-Rouillier L.,1997, ETUDE COMPARATIVE DES TECHNIQUES DE FILTRATION MEMBRANAIRE ET D'ADSORPTION SUR RESINES MACROPOREUSES NON IONIQUES EN VUE DE L'EXTRACTION ET DE LA CARATERISATION DES MATIERE ORGANIQUES NATURELLES DISSOUTES D'EAUX DE SURFACE, These de Doctorat, University of Poitiers. Leenheer J.A and T.I. Noyes, 1984, A FILTRATION AND COLUMN-ADSORPTION SYSTEM FOR ONSITE CONCENTRATION AND FRACTIONATION OF ORGANIC SUBSTANCES FROM LARGE VOLUMES OF WATER, U.S. Geological Survey Water Supply Paper 2230, Washington DC, US. Government Printing Office, 2-16. Leenheer J.A and E.W.D. Huffman, 1976, CLASSIFICATION OF ORGANIC SOLUTES IN WATER BY USING MACRORETICULAR RESINS, J. Res. U.S. Geol. Surv., 4, 737-751. Leenheer J.A., 1981, COMPREHENSIVE APPROACH TO PREPARATIVE ISOLATION AND FRACTIONATION OF DISSOLVED ORGANIC CARBON FROM NATURAL WATERS AND WASTEWATERS, Environmental Science and Technology, may, 578-587. Leenheer J.A., 1997, ISOLATION, FRACTIONATION AND CHARACTERIZATION OF NATURAL ORGANIC MATTER IN DRINKING WATER, AWWARF Report, 33-105. Malcolm R.L., J.P. Croue and B. Martin, 1993, Isolation of XAD-4 acids from natural waters and their importance as precursors to TOX and THM upon chlorination, to presented at DELFT CONGRESS, Sept. 13-18, 1-34. Malcolm R.L. and P. Mac Carthy, 1992, QUANTITATIVE EVALUATION OF XAD-8 AND XAD-4 RESINS USED IN TANDEM FOR REMOVING ORGANIC SOLUTES FROM WATER, Environment International, 18, 597-607. Martin B., 1995, LA MATIÈRE ORGANIQUE NATURELLE DISSOUTE DES EAUX DE SURFACE : FRACTIONNEMENT, CARACTÉRISATION ET RÉACTIVITÉ, Thèse de Doctorat, Université de Poitiers. Reckhow D. , 1993, Sun L. Perdue E. and J.F. MacCArthy, 1995, USING REVERSE OSMOSIS TO OBTAIN ORGANIC MATTER FROM SURFACE AND GROUNDWATERS, Wat. Res., 29, 1471-1477. Thurman E.M. and R.L Malcolm, 1981, PREPARATIVE ISOLATION OF AQUATIC HUMIC SUBSTANCES, Environ Sci. Technol., 15, 463-466. Thurman E.M., 1985, DEVELOPMENTS IN BIOCHEMISTRY : ORGANIC GEOCHEMISTRY OF NATURAL WATERS, M. Nijhff, Dr W. Junk Publishers, Drodrecht.