Ecological invertebrate habitat survey, March

advertisement

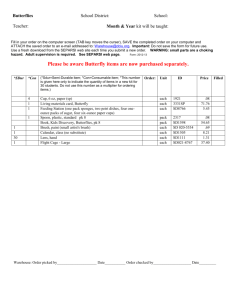

ECOLOGICAL INVERTEBRATE HABITAT SURVEY VELE COLLIERY Hodogenes troglodytes, rock scorpion, a delicate scorpion which can become very large (individual in picture is young) and which is restricted to some rocky patches at the site. Photo: R.F. Terblanche February 2012 MARCH 2012 COMPILED BY: Reinier F. Terblanche (M.Sc, Cum Laude; Pr.Sci.Nat, Reg. No. 400244/05) 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 1 2. STUDY AREA ................................................................................................... 1 3. METHODS ......................................................................................................... 1 4. RESULTS .......................................................................................................... 4 5. DISCUSSION .................................................................................................... 14 6. IMPACT ASSESSMENT .................................................................................. 21 7. RECOMMENDATION ....................................................................................... 23 8. CONCLUSION .................................................................................................. 26 9. REFERENCES .................................................................................................. 28 APPENDIX 1: LIST OF SCORPION SPECIES ............................................ 35 APPENDIX 2: LIST OF BUTTERFLY SPECIES ............................................ 36 2 1 INTRODUCTION An ecological habitat survey of invertebrates, of known high conservation priority, was required for the Vele mine area in the Limpopo Province. The survey focused on the possibility that invertebrate species, especially arachnids (which include scorpions and baboon spiders) listed in the TOPS list are likely to occur at the site or not. Known threatened invertebrate species of the Limpopo Province which are based on IUCN categories and criteria have also been incorporated including the recently published South African Red Data Book: butterflies (Henning, Terblanche & Ball 2009). 2 STUDY AREA The study area is approximately 40km west of Mucina in the Limpopo Province at the Vele mine site. Low ridges are are embedded in gentle slopes towards a sandy alluvial plain at the banks of the Limpopo river. The site is part of the Savanna biome. Savanna on the flatter areas with gentle slopes is represented by Musina Mopane Bushveld. Savanna at the low ridges is part of the Limpopo Ridge Bushveld (Mucina & Rutherford 2006). Subtropical Alluvial Vegetation occurs on the banks of the Limpopo river (Mucina & Rutherford 2006). Croplands and orchards are present between the low rocky ridges and Limpopo river. Some vegetation has also been transformed by mining. The area is characterised by summer rainfall and very dry winters (MAP 300-400mm) (Mucina & Rutherford 2006). High maximum temperatures in the summer and in general frost-free winters are present. 3 METHODS A desktop study comprised not only an initial phase, but also it was used throughout the study to accommodate and integrate all the data that become available during the field observations. Invertebrate habitat surveys that consisted of visits by R.F. Terblanche from 1-3 February 2012 were conducted to note key elements of habitats on the site, relevant to the description and conservation of invertebrate fauna at the site. The following sections highlight the materials and methods applicable to different aspects that were observed. 3.1 HABITAT CHARACTERISTICS AND VEGETATION The habitat was investigated by noting habitat structure (rockiness, slope, plant structure/physiognymy) as well as floristic composition. Voucher specimens of plant species were only taken where the taxonomy was in doubt and where the plant specimens were of significant relevance for invertebrate conservation. Field guides such as those by Germishuizen (2003), Manning (2003), Manning (2009), Van Oudtshoorn (1999), Van Wyk (2000), Van Wyk & Malan (1998) and Van Wyk & Van Wyk (1997) were used to confirm the taxonomy of the 3 species. Works on specific plant groups (often genera) such as those by Goldblatt (1986), Goldblatt & Manning (1998), Jacobsen (1983), McMurtry, Grobler, Grobler & Burns (2008), Smit (2008), Van Jaarsveld (2006) and Van Wyk & Smith (2003) were also consulted to confirm the identification of species. In this case no plant specimens were needed to be collected as voucher specimens or to be send to a herbarium for identification. For the most recent treatise of scientific plant names and broad distributions, Germishuizen, Meyer & Steenkamp (2006) as well as Raimondo, Von Staden, Foden, Victor, Helme, Turner, Kamundi and Manyama (2009) were followed to compile the lists of species. 3.2 BUTTERFLIES Butterflies were noted as sight records or voucher specimens. Voucher specimens are mostly taken of those species of which the taxa warrant collecting due to taxonomic difficulties or in the cases where species can look similar in the veldt. Many butterflies use only one species or a limited number of plant species as host plants for their larvae. Myrmecophilous (ant-loving) butterflies such as the Aloeides, Chrysoritis, Erikssonia, Lepidochrysops and Orachrysops species (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae), which live in association with a specific ant species, require a unique ecosystem for their survival (Deutschländer & Bredenkamp, 1999; Terblanche, Morgenthal & Cilliers, 2003; Edge, Cilliers & Terblanche, 2008; Gardiner & Terblanche, 2010). Known food plants of butterflies were therefore also recorded. After the visits to the site and the identification of the butterflies found there, a list was also compiled of butterflies that will most probably be found in the area in all the other seasons because of suitable habitat. The emphasis is on a habitat survey. 3.3 FRUIT CHAFER BEETLES Different habitat types in the areas were explored for any sensitive or special fruit chafer species. Selection of methods to find fruit chafers depends on the different types of habitat present and the species that may be present. Fruit bait traps would probably not be successful for capturing Ichnestoma species in a grassland patch (Holm & Marais 1992). Possible chafer beetles of high conservation priority were noted as sight records accompanied by the collecting of voucher specimens with grass nets or containers where deemed necessary. 3.4 MYGALOMORPH SPIDERS AND ROCK SCORPIONS Relatively homogenous habitat / vegetation areas were identified and explored to identify any sensitive or special species. The area was searched for possible signs of trap door spiders or other mygalomorph spiders (for example traces of wafer-lids, cork-lids or silk-lined burrows). Investigations by brushing the soil surface, scraping or digging into the soil with a spade, were made. All the above actions were accompanied by the least disturbance possible. 4 3.9 LIMITATIONS For the site visited, it should be emphasized that surveys can by no means result in an exhaustive list of invertebrates present on the site, because of the time constraint. The on site survey was conducted during February which is an optimal time of the year to find animals such as butterflies, other invertebrates as well as habitat sensitive plant species high conservation priority. In general the weather was optimal for recording of invertebrates. At the time of the survey the local area was very dry though. The focus of the survey remains sensitive habitats and species of particular conservation priority. 4 RESULTS 4.1 HABITAT AND VEGETATION CHARACTERISTICS Table 4.1: Outline of the main habitat and vegetation characteristics of the site proposed for development. HABITAT FEATURE Topography Rockiness Presence of wetlands Vegetation in general DESCRIPTION Plains with gentle slopes, sandy streambeds, low hills with some rocky outcrops and the banks of the Limpopo Province are all part of the landscape. Rocks are conspicuous at the rocky ridges, but patches with rocks have also been found on the flatter areas adjacent the low hills. Wetlands are confined to the riparian zones of the major drainage channels at the site and the Limpopo river. The vegetation in general ranges from pristine savanna at hills and some slopes to plains where savanna has been transformed by savanna. A mosaic of plant assemblages is present. The vegetation overall contains many indigenous plant species of which the life forms and structure varies considerably. From an invertebrate perspective habitats which contained a conspicuous dominance of Colophospermum mopane on sands, habitats with few rocks, including calcrete in some places where Colophospermum mopane is dominant but where Boscia albitrunca, Commiphora species, Grewia flava and other tree species are also well represented, ridge bushveld where Kirkia acuminata, Combretum apiculatum and various other tree species are recorded with Colophospermum mopane as well as the alluvial vegetation with remnants of riparian forest along the banks of the Limpopo river. Also 5 Signs of disturbances Characteristics of surrounding areas (with a view to buffer zones, corridors and connectivity of habitats with more natural vegetation) noteworthy the occurence of Acacia nigrescens along dry sandy streambeds and the occurence of Lonchocarpus capassa at drainage lines near the alluvial section of the Limpopo river. Orchards (citrus) and cotton fields replaced indigenous vegetation at plains at some areas between the low ridges and the Limpopo river. Excavations of mining activities are present as well as roads that link mining centres. There is scope for a number of conservation corridors and buffer zones of particular importance at the site, which need careful planning, considering the type of development, if approved. Photo 1 Low rocky ridge near the Limpopo river at Vele. Photo: February 2012, R.F. Terblanche. 6 Photo 2 View towards the north-east from low rocky ridge at the Vele site. Limpopo river with, riparian vegetation in the background. Mopane bushveld interrupted by agriculture in the foreground. Photo: February 2012, R.F. Terblanche. 7 Photo 3 View towards the north from highest rocky ridge at Vele. Mopane bushveld, croplands and orchards (citrus). Hill in the background part of Zimbabwe. Thin green strip in the background is alluvial vegetation at the banks of the Limpopo river. Photo: 3 February 2012, R.F. Terblanche. Photo 4 Air-strip with adjacent Mopane bushveld at Vele. Photo: February 2012, R.F. Terblanche. 8 Photo 5 Alluvial section with remnants of riparian forest. Photo: February 2012, R.F. Terblanche. Photo 6 Remnants of riparian forest near the banks of the Limpopo river. Photo: February 2012, R.F. Terblanche. 9 Photo 7 Hadogenes troglodytes is one of the TOPS listed scorpion species which appears to occur at many rocky patches at the site, including rocky patches, not only at the rocky hills but also at gentle slopes. Photo: February 2012, R.F. Terblanche. Photo 8 Parabuthus transvaalicus which appears to favour undersides of old dead trees at the site. Photo: February 2012, R.F. Terblanche. 10 Photo 9 Young Opistophthalmus wahlbergii. All Opistophthalmus scorpions are TOPS listed. Photo: February 2012, R.F. Terblanche. Photo 10 Charaxes jasius subsp. saturnus, a common resident at the site. Photo: February 2012, R.F. Terblanche. 11 Photo 11 Fruit baited trapnet (“Charaxes type trapnet”) at highest ridge near the Limpopo river at the site. The higher Dongola hill outside the site is visible in the background towards the south. Photo: February 2012, R.F. Terblanche. 12 4.2 INVERTEBRATE SPECIES OF PARTICULAR CONSERVATION PRIORITY 4.2.1 Butterflies of particular conservation priority Table 4.2 Threatened butterfly species of the Limpopo Province (Henning, Terblanche & Ball 2009). Invertebrates such as threatened butterfly species are often very habitat specific and residential status imply a unique ecosystem that is at stake. Species Red Listed Status Resident at site Recorded at site during survey Likely to be found based on habitat assessment Alaena margaritacea Wolkberg Zulu Critically Endangered No No No Aloeides stevensoni Stevenson’s Copper Vulnerable No No No Anthene crawshayi juanitae Juanita’s Ciliated Blue/Hairtail Vulnerable No No No Dingana clara Wolkberg Widow Vulnerable No No No Dingana jerinae Jerine’s Widow Vulnerable No No No Erikssonia edgei * Edge’s Acraea Copper Critically Endangered No No No Lepidochrysops lotana Lotana Blue Critically Endangered No No No Pseudonympha swanepoeli Swanepoel’s Brown Critically Endangered No No No Telchinia induna salmontana Soutpansberg Acraea Vulnerable No No No * Formerly this butterfly species has been known as the Waterberg population of Erikssonia acraeina. The Waterberg population of Erikssonia, known from only one locality, has recently been described as a new species, Erikssonia edgei by Gardiner & Terblanche (2010). 13 Table 4.2 Butterfly species of the Limpopo Province that is not threatened but of special conservation concern. Invertebrates such as threatened butterfly species are often very habitat specific and residential status imply a unique ecosystem that is at stake. Species Anthene liodes Liodes Ciliated Blue/Hairtail 4.2.2 Red Listed Status Resident at site Very restricted range in South Africa Recorded at site during survey Yes Likely to be found based on habitat assessment Yes Yes Beetles of particular conservation priority Table 4.4 Fruit chafer species (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Cetoninae) in the Limpopo Province which are of known high conservation priority. Species Red Listed Status Resident at site Recorded at site during survey Likely to be found based on habitat assessment Ichnestoma stobbiai Uncertain (Some population s maybe endanger ed: taxonomic difficulties) No No No Tmesorhina viridicyanea Uncertain/ rare No No No Trichocephala brincki Uncertain No No No 14 4.2.3 Scorpions of particular conservation importance Table 4.5 Scorpion species (Scorpiones: Ischnuridae) species that are of known high conservation priority in the Limpopo Province. Species Red List Status Resident at site Recorded at site during survey Likely to be found based on habitat assessment Hadogenes troglodytes Not threatened (but all Hadogenes species are on TOPS list) Yes Yes Yes Opistophthalmus wahlbergii Yes Not threatened (but all Opistophthal mus species are on TOPS list) Yes Yes 4.2.4 Mygalomorph spiders of particular conservation importance Table 4.6 Baboon spiders (Arachnida: Theraphosidae) species that are of known high conservation priority in the Limpopo Province. Species Red List Status Resident at site Recorded at site during survey Likely to be found based on habitat assessment 15 Ceratogyrys bechuanicus Not threatened (but all Ceratogyrus species are on TOPS list) ? No Possibly, yes (suitable habitat) Ceratogyrys brachycephalus Not threatened/ Uncertain (but all Ceratogyrus species are on TOPS list) ? No Possibly, yes (suitable habitat) Pterinochilus species (Pterinochilus junodi, P. pluridentatis) Not threatened (but all Pterinochilus species are on TOPS list) Yes No Yes 16 5 DISCUSSION 5.1 HABITAT AND VEGETATION CHARACTERISTICS A brief outline of the overall habitat and vegetation characteristics is given in Table 4.1. and serves as a reference for the invertebrate habitat survey. 5.2 INVERTEBRATES 5.2.1 Butterflies Assessment of threatened butterfly species Studies about the vegetation and habitat of threatened butterfly species in South Africa showed that ecosystems with a unique combination of features are selected by these often localised threatened butterfly species (Deutschländer and Bredenkamp 1999; Edge 2002, 2005; Terblanche, Morgenthal & Cilliers 2003; Lubke, Hoare, Victor & Ketelaar 2003). Threatened butterfly species in South Africa can then be regarded as bio-indicators of rare ecosystems. Table 4.2 lists nine butterfly species as threatened in the Limpopo Province such as given in the South African Red Data Book: butterflies (G.A. Henning, Terblanche & Ball 2009). The expected presence or not of these threatened butterfly species follows. Alaena margariticea (Wolkberg Zulu) The proposed global red list status for Alaena margariticea according to the most recent IUCN criteria and categories is Critically Endangered [CR A3ce; B2ab(i,ii,iii,iv,v)] (G.A. Henning, Terblanche & Ball 2009). Alaena margariticea is only known from one restricted area in the vicinity of Haenertsburg in the Wolkberg. The secluded colony is found on steep grassy slopes in the Wolkberg with where lichen covered rocks are a crucial part of the habitat (Henning, Terblanche & Ball 2009). No Alaena margaritacea was recorded on the site and it is highly unlikely that the butterfly will be present. Aloeides stevensoni (Stevenson’s Copper) The proposed global red list status for Aloeides stevensoni according to the most recent IUCN criteria and categories is Vulnerable [VU D2] (Henning, Terblanche & Ball 2009). Aloeides stevensoni colonies are found on south facing, high-altitude grassy slopes of the Wolkberg. There is not an ideal habitat of Aloeides stevensoni on the site and it is unlikely that the butterfly is present at the site. Anthene crawshayi juanitae (Juanita’s Ciliated Blue) The proposed global red list status for Anthene juanitae according to the most recent IUCN criteria and categories is Vulnerable [VU B1a(iv)c(iv)+2ab(iv)c(iv); D1+2] (Henning, Terblanche 17 & Ball 2009). From 1990 to 2011 Anthene juanitae was only known from six specimens from riverine vegetation on the banks of the Olifants River at Manoutsa Park (Henning, Terblanche & Ball 2009). Very recently the butterfly has been rediscovered by Gardiner at Manoutsa Park (November 2011) and by Williams (January 2012) at the Legalameetse Nature Reserve. There appears to be no ideal habitat of Anthene juanitae on the site and it is unlikely that the butterfly is present at the site. Dingana clara (Wolkberg Widow) The proposed global red list status for Dingana clara according to the most recent IUCN criteria and categories is Vulnerable [VU D2] (Henning, Terblanche & Ball 2009). Dingana clara is known from only four small montane localities in the Wolkberg area of the Limpopo Province. Adults are found on steep, rock-strewn, grassy slopes as high elevations among proteas (Henning, Ball & Terblanche, 2009). There is not an ideal habitat of Dingana clara on the site and it is unlikely that the butterfly is present at the site. Dingana jerinae (Jerine’s Widow) The proposed global red list status for Dingana jerinae according to the most recent IUCN criteria and categories is Vulnerable [VU D2] (Henning, Terblanche & Ball 2009). Dingana jerinae is only known from the Kransberg part of the Waterberg where one of its localities extends into the Marekele National Park. Adults fly on steep slopes, below high cliffs, among fallen rocks as well as in rocky terrain on the summits (Henning, Terblanche & Ball 2009). There is not an ideal habitat of Dingana jerinae on the site and it is unlikely that the butterfly is present at the site. Erikssonia edgei (Edge’s Acraea Copper) Erikssonia edgei was previously referred to as the Waterberg population of Erikssonia acraeina before it was described as a new species from South Africa by Gardiner & Terblanche (2010). The proposed global red list status for Erikssonia edgei (hitherto known as the South African population of Erikssonia acraeina) according to the most recent IUCN criteria and categories is Critically Endangered [CR A1ac+2a; B1ab(iii,v)c(iv) + 2ab(iii,v)c(iv)] (Henning, Terblanche & Ball 2009). Erikssonia edgei is only known from one restricted area in the vicinity of Rankin’s Pass on deep sands of the Waterberg (Henning, Terblanche & Ball 2009; Gardiner & Terblanche 2010). No Erikssonia edgei was recorded on the site and it is highly unlikely that the butterfly will be present. Lepidochrysops lotana (Lotana Blue) The proposed global red list status for Lepidochrysops lotana according to the most recent IUCN criteria and categories is Critically Endangered [CR B1ab(i,ii,iii,iv,v) + 2a(i,ii,iii,iv,v)] (Henning, Terblanche & Ball 2009). The type locality where the butterfly was first discovered is on the farm Rietvlei 30km south of Polokwane. Another locality is known on the Wolkberg east of Polokwane and very recently the butterfly was found in the Legalemeetse Nature Reserve by M.C. Williams. The butterfly is present where the larval host plant Ocimum obovatum occurs on grassy slopes (Henning, Terblanche & Ball 2009). Note that the distribution of the butterfly is 18 much more restricted than the distribution of the host plant. No Lepidochrysops lotana was recorded on the site and it is highly unlikely that the butterfly will be present. Pseudonympha swanepoeli (Swanepoel’s Brown) The proposed global red list status for Pseudonympha swanepoeli according to the most recent IUCN criteria and categories is Critically Endangered [CR B2ab(i,ii,iii,iv,v)] (Henning, Terblanche & Ball 2009). Pseudonympha swanepoeli is only known from one restricted marshy area near Houtbosdorp in the Wolkberg mountains. Previously known localities of the butterfly in the vicinity of Houtbosdorp have been destroyed (Henning, Terblanche & Ball 2009). No Pseudonympha swanepoeli was recorded on the site and it is highly unlikely that the butterfly will be present. Telchinia induna salmontana (Soutpansberg Acraea): The proposed global red list status for Telchinia induna salmontana according to the most recent IUCN criteria and categories is Vulnerable [VU B2ab(iii)] (Henning, Terblanche & Ball 2009). Telchinia induna salmontana is found in Soutpansberg Summit Sourveld (Mucina & Rutherford 2006) on the higher peaks in the Soutpansberg Mountains. Adults fly along exposed high rocky ridges where the food plant of the larva, Aeschynomene nodulosa, grows (Henning, Ball & Terblanche 2009). There is not an ideal habitat of Telchinia induna salmontana on the site and it is unlikely that the butterfly is present at the site. Conclusion on threatened butterfly species There appears to be no threat to any red listed butterfly species if the study site were developed. Assessment of butterfly species which are not threatened but of particular conservation concern Anthene liodes bihe A new locality for Anthene liodes bihe has been discovered at the remnants of riparian forest at the banks of the Limpopo river during this survey. This marginal species (with tropical affinity) is not threatened, but are well-known to be rare in South Africa with only a few localities from which it has been recorded in this country (Kloppers & Van Son 1978, Pringle, Ball & Henning 1994, Woodhall 2005). It has been described in 1847 but only in 1966 was the first specimen to be recorded in South Africa, caught at Balule on the Olifants river in the Kruger National Park by J. Kloppers (Kloppers & Van Son 1978). Another locality in the Kruger National Park is Punda Maria (Kloppers & Van Son 1978). Other known localities include habitats near Malelane and Komatipoort in Mpumalanga, Rondalia Ranch and Pafuri in the Limpopo Province as well as Pongola river below the Yozini dam (Pringle, Ball & Henning 1994, Woodhall 2005). Butterfly diversity High butterfly diversity appears to be present on the site, owing to the remaining natural vegetation as well as micro-habitat diversity. A preliminary list of seventy-four butterfly species is given based on the habitat survey of February 2012. This is unlike the Legalameetse Nature Reserve in the Limpopo Province where numerous endemic butterfly species could be found 19 and the species richness is 183 species, approaching 200 (Terblanche & Henning 1994). Overall, highly endemic butterfly species that are found in the Limpopo Province in the Wolkberg and on the Soutpansberg are absent from the series of low rocky hills on the site. Yet an interesting butterfly diversity is present. 5.2.2 Fruit chafer beetles Assessment of threatened or other high conservation priority fruit chafer beetle species Table 4.4 lists the fruit chafer beetle species (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Cetoninae) that are of possible high conservation priority in the Limpopo Province. No Ichnestoma species or Trichocephala brincki were found during the surveys. There appears to be no suitable habitat for these localised fruit chafer beetles at the site. There appears to be no threat to any of the fruit chafer beetles of particular high conservation priority if the site is developed. Fruit chafer beetle diversity During the site visits of February 2012 a number of fruit chafer beetle species were observed on the site. Because of time constraint, fruit chafer diversity was not explored in detail. The focus of this initial exploration was to look out for possible habitats of known rare and localised fruit chafer beetles. 5.2.3 Scorpions Assessment of threatened or other high conservation priority scorpion species Table 4.5 lists scorpion species that are of known high conservation priority in the Limpopo Province. Hadogenes troglodytes, a rock scorpion that is not a threatened species, has been found at the site during the February 2012 site visits. Though not threatened, all Hadogenes species are perceived to be quite habitat sensitive and on the TOPS list. Hadogenes troglodytes is particularly sensitive to habitat destruction owing to its small brood size and slow rate of reproduction (Leeming 2003). Hadogenes troglodytes is restricted to discrete rocky outcrops and mountain ranges in the northern parts of South Africa and further north in Zimbabwe and Mozambique (Leeming 2003). Hadogenes troglodytes is the longest scorpion in the world (up to 210mm). Opistophthalmus wahlbergii (a burrowing scorpion) has also been found at the site. Opistophthalmus is also on the TOPS list. There appears to be no known threatened scorpion species on the site. Scorpion diversity A preliminary list of nine scorpion species is given based on the survey of of February 2012 at the site (Appendix 1). These scorpions occupy various microhabitat types and are a reflection of the habitat diversity present on the site. The scorpion species recorded are widespread in the South African savanna though the rock scorpion, Hadogenes troglodytes, is restricted to rocky outcrops and mountains where significant rocky ridges are present. On the site however, 20 Hadogenes troglodytes appears to be present at vairous rocky patches, not only on slopes and summits of hills, but also on more flat terrain. There is clearly an interesting and highly diverse scorpion diversity at the site. 5.2.4 Mygalomorph spiders with special reference to baboon spiders Assessment of threatened or other high conservation priority baboon spider species Table 4.6 lists baboon spider species (Araneae: Theraphosidae) that are of known high conservation priority in the Limpopo Province. In the South African context baboon spider species belonging to the genus Ceratogyrus has a particular presence in the Limpopo Province. Ceratogyrus (“horned baboon spiders”) is also of importance to the pet trade and appears on the TOPS list with other baboon spider genera Harpactira and Pterinochilus. Despite intensive searching for burrows and in a variety of habitats presence of Ceratogyrus species at the site, only two abandoned burrows were found, which may belong to Ceratogyrus at the southern slopes near the summit of the highest rocky ridge near the Limpopo river, but the identity could not be confirmed. Ceratogyrus bechuanicus and Ceratogyrus brachycephalus appear to be only found to occur in small colonies of a few burrows scattered over wide area at each locality (De Wet & Schoeman 1991). This is in contrast to other baboon spider species such as Pterinochilus which is found in much larger colonies. Distribution of Ceratogyrus bechuanicus ranges from Botswana, Central Namibia, Zimbabwe (widespread), Mozambique to the northern parts of South Africa (Limpopo Province) (Dippenaar-Schoeman 2002). Ceratogyrus bechuanicus has also been recorded from the western Soutpansberg (Foord, Dippenaar-Schoeman & Van der Merwe 2002). In contrast to Ceratogyrus bechuanicus, Ceratogyrus brachycephalus has a much more restricted distribution, being confined to localities in central Botswana, southern Zimbabwe and the extreme northern Limpopo (De Wet & Dippenaar-Schoeman 1991; Dippenaar-Schoeman 2002). Burrows of Ceratogyrus can be found in different types of soils, ranging from sandy to very hard, compacted soils in areas sparsely covered with grass (De Wet & Dippenaar-Schoeman 1991). Most burrows are J-shaped (De Wet & Dippenaar-Schoeman 1991). In arid regions the burrow of baboon spiders (Theraphosidae) are usually deep to provide protection from high temperatures (Smith 1990). Adult males are usually not found in burrows and actively seeking females, freely wandering at night, and may also be shorter-lived than the females (De Wet & Dippenaar-Schoeman 1991; De Wet & Schoonbee 1991). Pitfall traps are found to be unsuccessful, as the males of Ceratogyrus are not easily captured in this manner (De Wet & Schoonbee 1991). Ceratogyrus bechuanicus is well-represented in the Kruger National Park, Musina, D’nyala and Atherstone Nature Reserves as well as in the Klaserie and Sabi Sand private nature reserves (De Wet & Schoonbee 1991). Ceratogyrus brachycephala has only been found in the Messina Provincial Nature Reserve whilst its historic distribution includes the Langjan Nature Reserve 21 (De Wet & Schoonbee 1991). Ceratogyrus brachycephala with its much smaller distribution has a higher conservation priority than Ceratogyrus bechuanicus. Since Ceratogyrus species are found in areas sparsely covered with grass, a balanced utilisation of habitat must be prescribed, and for management purposes the complete ecosystem must thus be taken into account (De Wet & Schoonbee 1991). Though De Wet & Schoonbee (1991) recommended determination of veld condition boundaries of habitats where colonies of Ceratogyrus occur, no detailed habitat study could be tracked in an extensive literature survey for this study. There appears to be no threatened baboon spider species at the site, though more research is necessary to inform the ecological management plan if the development is approved. Baboon spider diversity A diversity of microhabitats are present at the site which are likely to include habitats of Ceratogyrus species which appear on the TOPS list. 6 IMPACT ASSESSMENT AND MITIGATION MEASURES A review of possible impacts are given with a view to rehabilitation and partial restoration that should address these anticipated impacts as far as possible if the development (mining) is aproved. Habitat conservation is the key to the conservation of invertebrates such as threatened butterflies (Deutschländer and Bredenkamp 1999; Edge 2002, 2005; Terblanche, Morgenthal & Cilliers 2003; Lubke, Hoare, Victor & Ketelaar 2003; Edge, Cilliers & Terblanche, 2008). Furthermore corridors and linkages may play a significant role in insect conservation (Pryke & Samways, 2003, Samways, 2005). Habitats of threatened plants are in danger most often due to urban developments such as is the case for the Limpopo Province (Pfab & Victor, 2002). Urbanisation is a major additional influence on the loss of natural areas (Rutherford & Westfall 1994). In South Africa the pressure to develop areas are high since its infrastructure allows for improvement of human well-being in some way. Nevertheless the conservation of habitats is the key to invertebrate conservation, especially for those red listed species that are very habitat specific. This is also true for any detailed planning of corridors and buffer zones for invertebrates. Though proper management plans for habitats are not in place, setting aside special ecosystems is in line with the resent Biodiversity Act (2004) of the Republic of South Africa. Corridors are important to link ecosystems of high conservation priority. Such corridors or linkages are there to improve the chances of survival of otherwise isolated populations (Samways, 2005). How wide should corridors be? The answer to this question depends on the conservation goal and the focal species (Samways, 2005). For an African butterfly assemblage this is about 250m when the corridor is for movement as well as being a habitat source (Pryke 22 and Samways 2003). Hill (1995) found a figure of 200m for dung beetles in tropical Australian forest. In the agricultural context, and at least for some common insects, even small corridors can play a valuable role (Samways, 2005). Much more research remains to be done to find refined answers to the width of corridors in South Africa. The width of corridors will also depend on the type of development, for instance the effects of the shade of multiple story buildings will be quite different from that of small houses. To summarise: In practice, as far as urban, industrial or mining developments are concerned, the key would be to prioritise and plan according to special ecosystems. In the case of this study site, many areas of the site overall appear to be in a fair condition while others are in a poor and severely degraded condition and some extensively transformed by agriculture or mining. There appears to be no loss of threatened fauna and flora but there may be a loss of abundances of TOPS species, particularly scorpion species such as the rock scorpion, Hadogenes troglodytes. Therefore their appears to be a moderate loss of habitat but the full scale of this loss can only be estimated once a better idea of the lay-out of developments are available. A loss of conservation corridors of particular significance is likely if the mining takes place on the rocky hills, especially the upper slopes or summits and at the major drainage lines. For a more refined ecological impact assessment the location of the mining impacts are to be understood more properly. 23 7 RECOMMENDATIONS Recommendation for follow-up surveys and analyses: A survey for Ceratogyrus species should be continued and include visits following rain. Quantitative butterfly surveys and fruit chafer beetle surveys are viable options to add to the bio-indicators on the site. Pitfall-traps may also be considered for epigeal fauna in particular ants. Recommendations if the development is aproved (including mitigation measures): The least possible developments are recommended for the areas that contains rocky ridges. The least possible developments are recommended for the areas that contain drainage lines, these include sandy streambeds which are dry on the surface for the better part of a year. Measures to mitigate the riparian (or wetland) zones along water courses and ridges in the less sensitive matrix should be refined and followed. An ecological management plan for the possible mining developments should be compiled by a team of engineers, planners, soil expert, hydrology expert, air pollution expert and ecologist. For the ecological management plan the following key issues have been identified and are given in the section that follows. Ecological management plan: An ecological management plan is imperative, but need to be constructed with a clear idea of the type and location of developments, if approved. This ecological management plan should at least include the following: An appropriate strategy for the rehabilitation of impacted sites. Partial of full restoration should only be considered for areas less impacted or adjacent the possible development of a tailings storage facility. Owing to the nature of developments full restoration may not be possible in all the cases if the development is approved. Partial restoration of low rocky ridges and their buffer zones or riparian zones and their buffer zones where impacted by proposed development or previous impacts (agriculture, alien invasive species, overgrazing). 24 The water run-off system of the whole area would deserve attention. Conservation of upper layer of would be very important for the rich arachnid fauna at the site which include TOPS listed species. Control of exotic and alien invasive plant species. Exotic invasive plant species may spread from disturbed areas to the adjacent by various means. Exotic plant species cover habitat that would have been otherwise available for indigenous invertebrate species. Furthermore, exotic plant species may also decrease the quality of habitat or attract unwanted fauna. Minimization of edge effects: Pollutants Ecological monitoring is required for the area in which the Vele mining development is taking place (elsewhere referred to as the site) to determine its ecological status more clearly. The monitoring should be broken down into a twofold approach which is in line with the Biodiversity Act of 2004. Conservation priorities were identified by 1) verifying the presence or not of species and subspecies of particular high conservation priority (which was largely done in this and previous studies) and by 2) describing biodiversity for future references. The first step of this description of biodiversity would be species lists that serve as a biodiversity inventory for future references and planning. Monitoring of biodiversity should focus on invertebrate fauna at the site to provide: 1) Integration of biodiversity information from all the surveys up to date with the aim at formulating possible impacts and constructing a practical ecological management plan. 2) Providing a basis for more informed decisions on possible ecological management plans, partial restoration or rehabilitation. Monitoring differs from survey, the latter often being more of a once only inventory (Goldsmith, 1991). Monitoring is purpose orientated, repeated at regular intervals and often provides the baseline for possible change in the future (Goldsmith, 1991). In the case of this study the purpose of the monitoring should be to note the present ecological state and possible future changes, if further mining of coal has been approved. Monitoring actions in different seasons of the year often provides diverse but complementary insights much needed for an informative baseline of data. Faunal surveys such as butterfly and scorpion studies should be added to the vegetation studies to serve as additional bioindicator for monitoring purposes. Note that many more factors than only floristic diversity regulate faunistic diversity. The main objective overall is to compile and inventory of biodiversity so that management plans and management of rehabilitation or partial restoration, should the development be aproved, can be enhanced. 25 8 CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR MANAGEMENT The biodiversity in general at the site is diverse and interesting and deserve careful planning if developments are approved. Endemism, considering invertebrate fauna, at the low rocky hills and flatter areas at the Vele mine are not as high and cannot compare to those of the Wolkberg and Soutpansberg regions of the Limpopo Province. Similarly no threatened species or near threatened species appears to be present. For example, none of the threatened butterfly species of the Wolkberg region or Soutpansberg region are present on the site. Invertebrate fauna of particular conservation priority have been found, in particular scorpions of the genus Hadogenes and Opistophthalmus. Note that though these species are on the TOPS list (as genera), none of these qualify for threatened status (Critically Endangered, Endangered or Vulnerable) according to the present IUCN system. There appears to be suitable habitat for both Ceratogyrus bechuanicus as well as the less widespread Ceratogyrus brachycephala at the site, both these baboon spider species are on the TOPS list. Main findings are summarised beneath: No suitable habitats of any threatened butterfly species in South Africa were found and it is unlikely that any of these threatened butterfly species will be found on the site. No scorpions that are threatened or that are likely to be categorised as threatened in the near future are found on the site. One of the nine scorpion species that have been found at the site during the recent surveys in February 2012 Hadogenes troglodytes, a rock scorpion, is considered to be of particular conservation concern owing to their possible sensitivity to changes in the environment. Overall the low rocky hills and riparian zone of the Vele mine area appear to be more sensitive than the flatter areas where agriculture has also transformed some areas. Present efforts to monitor alien invasive plant species are to be commended and should be continued in the interest of invertebrate conservation. The riparian zone along the Limpopo river is of particular importance. For example a tropical butterfly species, Anthene liodes, which after centuries of exploration has been found to be clearly scarce and restricted in South Africa. This riparian zone should as far as possible be maintained as a mosaic because the alternation of open areas, forest and alluvial vegetation appear to be ideal for invertebrate conservation. The presence of more sensitive habitat and species of particular conservation priority adjacent impacted areas (where the mining occurs) could be monitored because their long preservation in the area maybe possible with careful planning. In this regard an audit of the biodiversity of the granite hills and Dongola which fell outside the scope of the present study would improve the perspective of invertebrate conservation in the area. 26 Finally it appears that there is no threat to threatened invertebrate species at the site, if the development is approved. Yet there is for example an interesting arachnid and butterfly diversity which underlines the importance of a mosaic of ecosystems at the site. Monitoring and more surveys could shed more light on this biodiversity and is likely, if the development is approved, to improve the knowledge on which an ecological management plan could be based. 27 9 REFERENCES Bromilow, C. 2001. Problem Plants of South Africa. Pretoria: Briza Publications. De Wet, J.I. & Dippenaar-Schoeman, A.S. 1991. A revision of the genus Ceratogyrus Pocock (Araneae: Therphosidae). Koedoe 34(2): 39-68. De Wet, J.I. & Schoonbee, H.J. 1991. The occurrence and conservation status of Ceratogyrus bechuanicus and C. brachycephalus in the Transvaal, South Africa. Koedoe 34(2): 69-75. Deutschländer, M.S. & Bredenkamp, C.J. 1999. Importance of vegetation analysis in the conservation management of the endangered butterfly Aloeides dentatis subsp. dentatis (Swierstra) (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae). Koedoe 42(2): 1-12. Dippenaar-Schoeman, A.S. 2002. Baboon and trapdoor spiders in southern Africa: an identification manual. Plant Protection Research Institute Handbook No. 13. Pretoria: Agricultural Research Council. Dippenaar-Schoeman, A.S. & Jocqué, R. 1997. African spiders: an identification manual. Plant Protection Research Institute Handbook No. 9. Pretoria: Agricultural Research Council. Edge, D.A. 2002. Some ecological factors influencing the breeding success of the Brenton Blue butterfly, Orachrysops niobe (Trimen) (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae). Koedoe, 45(2): 19-34. Edge, D.A. 2005. Ecological factors influencing the survival of the Brenton Blue butterfly, Orachrysops niobe (Trimen) (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae). North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa (Thesis - D.Phil.). Edge, D.A., Cilliers, S.S. & Terblanche, R.F. 2008. Vegetation associated with the occurrence of the Brenton blue butterfly. South African Journal of Science 104: 505 - 510. Filmer, M.R. 1991. Southern African spiders: an identification guide. Cape Town: Struik. Foord, S.H., Dippenaar-Schoeman, A.S. & Van der Merwe, M. 2002. A check list of the spider fauna of the Western Soutpansberg, South Africa (Arachnida: Araneae). Koedoe 45(2): 3543. Gardiner, A.J. & Terblanche, R.F. 2010. Taxonomy, biology, biogeography, evolution and conservation of the genus Erikssonia Trimen (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae). African Entomology 18(1): 171 – 191. Germishuizen, G. 2003. Illustrated guide to the wildflowers of northern South Africa. Briza, Pretoria. 224 p. 28 Germishuizen, G., Meyer, N.L. & Steenkamp (eds) 2006. A checklist of South African plants. Southern African Botanical Diversity Network Report No. 41. SABONET, Pretoria. Goldblatt, P. 1986. The Moraeas of Southern Africa. Annals of Kirstenbosch Botanic Gardens, Volume 14. National Botanic Gardens, Cape Town. 224 p. Goldblatt, P. & Manning, J. 1998. Gladiolus in Southern Africa. 320 p. Henderson, L. Alien weeds and alien invasive plants: a complete guide to the declared weeds and invaders in South Africa. Plant Protection Research Institute Handbook No. 12. Pretoria: ARC: Plant Protection Research Institute. Henning, G.A. & Roos, P.S. 2001. Threatened butterflies of South African wetlands. Metamorphosis 12(1): 26-33. Henning, G.A., Terblanche, R.F. & Ball, J.B. (eds) 2009. South African Red Data Book: butterflies. SANBI Biodiversity Series No 13. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria. 158 p. Henning, S.F. 1983. Biological groups within the Lycaenidae (Lepidoptera). Journal of the Entomological Society of Southern Africa 46(1): 65-85. Henning, S.F. 1987. Outline of Lepidoptera conservation with special reference to ant associated Lycaenidae. Proceedings of the first Lepidoptera conservation Symposium, Roodepoort: Lepidopterists’ Society of southern Africa: 5-7. Henning, S.F. & Henning, G.A. 1989. South African Red Data Book: butterflies. South African National Scientific Programmes Report No. 158. Pretoria: CSIR. 175 p. Hill, C.J. 1995. Conservation corridors and rainforest insects. (In Watt, A.D., Stork, N.E. & Hunter, M.D. (eds.), Forests and Insects. London: Chapman & Hall. p. 381-393.) Holm, E. & Marais, E. 1992. Fruit chafers of southern Africa. Hartebeespoort: Ekogilde. IUCN. 2001. IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria: Version 3.1. IUCN Species Survival Commission. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK. Kloppers, J. & Van Son, G. 1978. Butterflies of the Kruger National Park. National Parks Board of Trustees, Pretoria. Kudrna, O. 1995. Conservation of butterflies in central Europe. (In Pullin, A. S. ed. Ecology and conservation of butterflies. London: Chapman & Hall. p. 248-257.) 29 Larsen, T.B. 1995. Butterfly biodiversity and conservation in the Afrotropical region. (In Pullin, A.S. ed. Ecology and conservation of butterflies. London: Chapman & Hall. p. 290-303.) Leeming, J. 2003. Scorpions of southern Africa. Cape Town: Struik. Leroy, A. & Leroy, J. 2003. Spiders of southern Africa. Cape Town: Struik. Low, A.B. & Rebelo, A.G. (Eds.) 1996. Vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. Pretoria: Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism. Lubke, R.A., Hoare, D., Victor, J. & Ketelaar, R. 2003. The vegetation of the habitat of the Brenton Blue Butterfly, Orachrysops niobe (Trimen), in the Western Cape, South Africa. South African Journal of Science 99: 201-206. Manning, J. 2003. Photographic guide to the wild flowers of South Africa. Briza, Pretoria. p. Manning, J. 2009. Field guide to the wild flowers of South Africa. Struik, Cape Town. 352 487 p. McMurtry, D., Grobler, L., Grobler, J. & Burns, S. 2008. Field guide to the orchids of northern South Africa and Swaziland. Umdaus Press, Hatfield. 482 p. Mucina, L. & Rutherford, M.C. eds. 2006. The vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. Strelitzia 19. Pretoria: South African National Biodiversity Institute. 807 p. Munguira, M.L. 1995. Conservation of butterfy habitats and diversity in European Mediterranean countries. (In Pullin, A.S. ed. Ecology and conservation of butterflies. London: Chapman & Hall. p. 277- 289.) New, T.R. 1993. ed. Conservation biology of Lycaenidae (butterflies). Occasional paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 8. 173 p. New, T.R. 1995. Butterfly conservation in Australasia – an emerging awareness and an increasing need. (In Pullin, A.S. ed. Ecology and conservation of butterflies. London: Chapman & Hall. p. 304 – 315.) Oates, M.R. 1995. Butterfly conservation within the management of grassland habitats. (In Pullin, A.S. ed. Ecology and conservation of butterflies. London: Chapman & Hall. (p. 98112.) Opler, P.A. 1995. Conservation and management of butterfly diversity in North America. (In Pullin, A.S. ed. Ecology and conservation of butterflies. London: Chapman & Hall. p. 316324.) 30 Picker, M., Griffiths, C. & Weaving, A. 2004. Field guide to insects of South Africa. 2 nd ed. Cape Town: Struik. Pooley, E. 1998. A field guide to wild flowers of KwaZulu-Natal and the eastern region. Natal Flora Publications Trust, Durban. 630 p. Pringle, E.L., Henning, G.A. & Ball, J.B. eds. 1994. Pennington’s Butterflies of Southern Africa. Cape Town: Struik Winchester. Pryke, S.R. & Samways, M.J. 2001. Width of grassland linkages for the conservation of butterflies in South African afforested areas. Biological Conservation 101: 85-96. Pullin, A.S. ed. 1995. Ecology and conservation of butterflies. London: Chapman & Hall. 363 p. Raimondo, D., Von Staden, L., Foden, W., Victor, J.E., Helme, N.A., Turner, R.C., Kamundi, D.A. & Manyama, P.A. (eds) 2009 Red list of South African Plants 2009. Strelitzia 25. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria. 668 p. Retief, E. & Herman, P.P.J. 1997. Plants of the northern provinces of South Africa: keys and diagnostic characteristics. Strelitzia 6. Pretoria: National Botanical Institute. Rutherford, M.C. & Westfall, R.H. 1994. Biomes of southern Africa: An objective categorisation, 2nd ed. Memiors of the Botanical Survey of South Africa, Vol. 63, pp. 1-94. Pretoria: National Botanical Institute. Samways, M.J. 2005. Insect diversity conservation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 342 p. Smit, N. 2008. Field guide to the Acacias of South Africa. Briza, Pretoria. 127 p. Smith, A.M. 1990. Tarantulas of Africa and the Middle East. Fitzgerald Publishing, London. South Africa. 2004. National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act No. 10 of 2004. Pretoria: Government Printer. Stuart, C. & Stuart, T. 2000. A field guide to the tracks and signs of Southern and East Africa. Cape Town: Struik. 310 p. Terblanche, R.F., Morgenthal, T.L. & Cilliers, S.S. 2003. The vegetation of three localities of the threatened butterfly species Chrysoritis aureus (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae). Koedoe 46(1): 73-90. 31 Terblanche, R.F. & Van Hamburg, H. 2003. The taxonomy, biogeography and conservation of the myrmecophilous Chrysoritis butterflies (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae) in South Africa. Koedoe 46(2): 65-81. Terblanche, R.F. & Van Hamburg, H. 2004. The application of life history information to the conservation management of Chrysoritis butterflies (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae) in South Africa. Koedoe 47(1): 55-65. Terblanche, R.F. & Edge, D.A. 2007. The first record of an Orachrysops in Mpumalanga. Metamorphosis 18(4): 131-141. Thomas, C.D. 1995. Ecology and conservation of butterfly metapopulations in the fragmented British landscape. (In Pullin, A.S. ed. Ecology and conservation of butterflies. London: Chapman & Hall. p. 46-64.) Van Jaarsveld, E.J. 2006. The Southern African Plectranthus and the art of turning shade to glade. 176 p. Van Oudtshoorn, F. 1999. Guide to grasses of southern Africa. Pretoria: Briza. Van Wyk, B. 2000. A photographic guide to wild flowers of South Africa. Struik, Cape Town. 144 p. Van Wyk, B. & Malan, S. 1998. Field Guide to the Wild Flowers of the Highveld. Cape Town:Struik. Van Wyk, B.E. & Smith, G.F. 2003. Guide to the aloes of South Africa. 2nd ed. Pretoria: Briza Publications. 304 p. Van Wyk, B. & Van Wyk, P. 1997. Field guide to trees of southern Africa. Cape Town: Struik. Warren, M.S. 1995. Managing local microclimates for the high brown fritillary, Argynnis adipe. (In Pullin, A.S. ed. Ecology and conservation of butterflies. London: Chapman & Hall.) Watt, A.D., Stork, N.E. & Hunter, M.D. (eds.), Forests and Insects. London: Chapman & Hall. (p. 381-393.) 32 Appendix 1 List of scorpion species that have been recorded at the site Compiled by R.F. Terblanche Sources of names and identifications: Leeming (2003) FAMILIES AND SPECIES COMMON NAMES ENGLISH/ AFRIKAANS FAMILY: BUTHIDAE THICK-TAILED SCORPIONS 1 Hottentotta trilineatus ...... 2 Parabuthus transvaalicus ...... 3 Pseudolychas pegleri ...... 4 Uroplectes flavoviridis ..... 5 Uroplectes planimanus ..... 6 Uroplectes vittatus ..... FAMILY ISCHNURIDAE ROCK SCORPIONS ..... 7 Opistacanthus asper 8 Hadogenes troglodytes Rock Scorpion FAMILY SCORPIONIDAE BURROWING SCORPIONS 9 Opistophthalmus wahlbergii Burrowing Scorpion Appendix 2 Preliminary list of butterfly species (Order Lepidoptera; superfamilies Papilionoidea, Hesperioidea) that have been or is likely to be recorded at the site Compiled by R.F. Terblanche Sources of names and identifications: Henning, Terblanche & Ball (2009); Pringle, Henning & Ball (1994); Woodhall (2005) FAMILIES, SUBFAMILIES AND SPECIES COMMON NAMES ENGLISH/ AFRIKAANS 33 FAMILY: PAPILIONIDAE SUBFAMILY PAPILIONINAE 1 2 3 SWALLOWTAIL FAMILY SWAELSTERTFAMILIE SWALLOWTAILS AND SWORDTAILS SWAELSTERTE EN SWAARDSTERTE Graphium angolanus angolanus Angola White Lady (Goeze, 1779) Angolawitnooientjie Papilio demodocus Citrus Swallowtail (Esper, 1798) Lemoenswaelstert Papilio nireus lyaeus Doubleday, 1845 FAMILY PIERIDAE Green-banded Swallowtail Groenlintswaelstert WHITES, YELLOWS AND TIPS WITJIES, GELETJIES EN PUNTJIES SUBFAMILY COLIADINAE YELLOWS AND CLOUDED YELLOWS GELETJIES EN WOLK-ORANJES 4 Catopsilia florella (Fabricius, 1775) 5 Colias electo electo (Linnaeus, 1763) 6 Eurema brigitta brigitta (Stoll, 1780) SUBFAMILY PIERINAE African Migrant Afrikaanse Migreerder African Clouded Yellow Afrikaanse wolk-oranje Broad-bordered Grass Yellow Grasveldgeletjie WHITES AND TIPS SUBFAMILY WITJIES EN PUNTJIES SUBFAMILIE 7 Belenois aurota aurota (Fabricius, 1793) 8 9 African Common White (Stoll, 1781) Afrikaanse Gewone Witjie Colotis antevippe gavisa Colotis eris eris (Klug, 1829) 11 12 Grasveldwitjie Belenois creona severina (Wallengren, 1857) 10 Brown-veined White Red Tip Rooipuntjie Banded Gold Tip Goudpuntjie Colotis euippe omphale Smoky Orange Tip (Godart, 1819) Donker-oranjepuntjie Colotis evinina evinina Common Orange Tip (Wallengren, 1857) Gewone Oranjepuntjie 34 13 14 Colotis regina Queen Purple Tip (Trimen, 1863) Koninginperspuntjie Colotis subfasciatus subfasciatus (Swainson, 1833) 15 Mylothris agathina agathina (Cramer, 1779) 16 Pinacopteryx eriphia eriphia (Godart, 1819) 17 Pontia helice helice (Linnaeus, 1764) FAMILY NYMPHALIDAE Lemon Traveller Tip Suurlemoensmous Common Dotted Border Gewone Spikkelrandjie/ Voëlentwitjie Zebra White Kwagga African Meadow White Bontrokkie BRUSH-FOOTED BUTTERFLIES BORSELPOOTSKOENLAPPERS SUBFAMILY DANAINAE MONARCH SUBFAMILY MONARG-SUBFAMILIE 18 Danaus chrysippus chrysippus (Linnaeus, 1758) SUBFAMILY CHARAXINAE African Monarch Afrikaanse Melkbosskoenlapper CHARAXES SUBFAMILY DUBBELSTERT SUBFAMILIE 19 Charaxes candiope (Godart, 1824) 20 Charaxes jahlusa rex Henning, S.F., 1978 21 Charaxes jasius saturnus Butler, 1866 SUBFAMILY SATYRINAE Greenveined Charaxes Skelmdubbelstert King Pearl-spotted Charaxes Koningsilwerkol-dubbelstert Saturn Foxy Charaxes Saturnus-koppiedubbelstert BROWNS SUBFAMILY BRUINTJIES-SUBFAMILIE 22 23 Henotesia perspicua perspicua Eyed Bush Brown (Trimen, 1873) Moerasbosbruintjie Ypthima impura paupera Bushveld Ringlet Ungemach, 1932 SUBFAMILY BIBLIDINAE Bosveld-ringetjie BYBLIA SUBFAMILY BIBLIA SUBFAMILIE 24 Byblia ilithyia Spotted Joker (Drury, 1773) Leliegrasvegter 35 SUBFAMILY NYMPHALINAE PANSY SUBFAMILY GESIGGIE SUBFAMILIE 25 Hypolimnas misippus (Linnaeus, 1764) 26 27 28 29 Common Diadem Gewone Na-aper/ Blouglans Junonia hierta cebrene Yellow Pansy Trimen, 1870 Geelgesiggie Junonia oenone oenone Blue Pansy (Linneaus, 1758) Blougesiggie Precis archesia archesia Garden Commodore (Cramer, 1779) Rots-blaarvlerk Vanessa cardui Painted Lady (Linnaeus, 1758) Sondagsrokkie SUBFAMILY HELICONIINAE ACRAEA SUBFAMILY ACRAEA SUBFAMILIE 30 Acraea anemosa Hewitson, 1865 31 32 Little Acraea (Westwood, 1881) Kuikenrooitjie Acraea caldarena caldarena Acraea encedon encedon (Linnaeus, 1758) 34 35 Black-tipped Acraea Swartpuntrooitjie White-barred Acraea Witstreep-rooitjie Acraea natalica natalica Natal Acraea De Boisduval, 1847 Natal-rooitjie Acraea neobule neobule Doubleday, 1847 36 Kersboomrooitjie Acraea axina Hewitson, 1877 33 Broad-bordered Acraea Wandering Donkey Acraea Dwaalesel-rooitjie Acraea serena Small Orange Acraea Fabricius, 1775 Klein-oranjerooitjie SUBFAMILY LIMENITIDINAE BUSH-GLIDER SUBFAMILY BOSDANSER SUBFAMILIE 37 Hamanumida daedalus Guineafowl Butterfly (Fabricius, 1775) Tarentaaltjie-skoenlapper FAMILY LYCAENIDAE BLUES AND COPPERS BLOUTJIES EN KOPERVLERKIES 36 SUBFAMILY THECLINAE HAIRSTREAKS AND COPPERS LANGSTERTE EN KOPERVLERKIES 38 Axiocerces tjoane tjoane (Wallengren, 1857) 39 40 Cigaritis natalensis Deudorix antalus Brown Playboy Deudorix dinochares Hypolycaena philippus philippus (Fabricius, 1793) 43 Natal Bar Natal-streepvlerkie Grose-Smith, 1887 42 Ralierooivlerkie (Westwood, 1852) (Hopffer, 1855) 41 Common Scarlet Iolaus sp. Bruinspelertjie Apricot Playboy Appelkoosspelertjie Purple-Brown Hairstreak Persbruin-stertbloutjie Sapphire species Safierspesie 44 Leptomyrina henningi Dickson, 1976 45 Myrina silenus ficedula Trimen, 1879 SUBFAMILY POLYOMMATINAE Henning’s Black-eye Henning-swartogie Common Fig-tree Blue Gewone Vyeboombloutjie BLOUTJIES AND CILIATED BLUES BLOUTJIES EN KORTSTERTJIES 46 47 Anthene amarah amarah Black-striped Hairtail (Guérin-Méneville, 1849) Swartstreep-kortstertjie Anthene butleri livida (Trimen, 1881) 48 Anthene contrastata mashuna (Stevenson, 1937) 49 50 51 52 Pale Hairtail Vaalkortstertjie Mashuna Hairtail Mashuna-kortstertjie Anthene definita definita Common Hairtail (Butler, 1899) Donkerkortstertjie Anthene liodes Liodes Hairtail (Hewitson, 1874) Liodes kortstertjie Anthene otacilia otacilia Otacilia Hairtail (Trimen, 1868) Boomkortstertjie Anthene princeps princeps (Butler, 1876) Cupreous Hairtail Koperglanskortstertjie 37 53 54 Azanus jesous jesous Topaz-spotted Blue (Guérin-Méneville, 1849) Hemels-kolbloutjie Azanus moriqua (Wallengren, 1857) 55 56 Azanus ubaldus 58 59 60 61 Chilades trochylus Grass Jewel Blue Eicochrysops messapus mahallakoaena Lampides boeticus Lucerne Blue (Linneaus, 1767) Lusernbloutjie Lepidochrysops plebeia plebeia Twin-spot Blue (Butler, 1898) Dubbelkolbloutjie Leptotes pirithous pirithous Common Blue (Linnaeus, 1767) Gewone bloutjie Pseudonacaduba sichela sichela Tarucus sybaris sybaris Tuxentius melaena melaena Zintha hintza hintza (Trimen, 1864) 65 Zizeeria knysna (Trimen, 1862) 66 Grassland Cupreous Copper Grasveldkoperbloutjie (Trimen, 1887) 64 Grasjuweeltjie (Wallengren, 1857) (Hopffer, 1855) 63 Velvet-spotted Blue Fluweel-kolbloutjie (Wallengren, 1857) 62 Doringboombloutjie (Stoll, 1782) (Freyer, 1843) 57 Thorn-tree Blue Zizula hylax (Fabricius, 1775) SUBFAMILY MILETINAE Dusky Blue Dowwebloutjie Dotted Blue Spikkelbloutjie Black Pie Swartbontetjie Hintza Blue Hintza-bontetjie Sooty Blue Duwweltjiebloutjie Gaika Blue Gaika-bloutjie SKOLLIES AND WOOLLY LEGS SKOLLIES EN WOLPOOTJIES FAMILY HESPERIIDAE SKIPPERS DARTELAARS SUBFAMILY COELIADINAE POLICEMEN KONSTABELS 38 67 68 Coeliades forestan forestan Striped Policeman (Stoll, 1782) Witbroekkonstabel Coeliades pisistratus Two-pip Policeman (Fabricius, 1793) Dubbelkolkonstabel SUBFAMILY PYRGINAE 69 70 Caprona pillaana Ragged Skipper Wallengren, 1857 Vaaljasdartelaartjie Eretis umbra umbra Small Marbled Elf (Trimen, 1862) 71 Gomalia elma elma (Trimen, 1862) 72 73 Leucochitonea levubu 76 Green-marbled Sandman Asjas-sandmannetjie White-cloaked Skipper Witjas-springertjie Spialia delagoae Delagoa Sandman Spialia depauperata australis De Jong, 1978 75 Umbra-kabouter Wallengren, 1857 (Trimen, 1898) 74 SANDMEN AND ELFINS SANDMANNETJIES EN ELWE Spialia dromus Delagoa-sandmannetjie Wandering Sandman Dwalende Sandmannetjie Forest Sandman (Plötz, 1884) Woudsandmannetjie Spialia spio Mountain Sandman (Linnaeus, 1764) SUBFAMILY HESPERIINAE Bergsandmannetjie RANGERS AND SWIFTS WAGTERTJIES EN RATSVLIEËRS 77 Gegenes niso niso (Linneaus, 1764) 78 Gegenes pumilio gambica (Mabille, 1878) Common Hottentot Skipper Gewone hotnot Dark Hottentot Skipper Donkerhotnot 39