Insuring Agreement

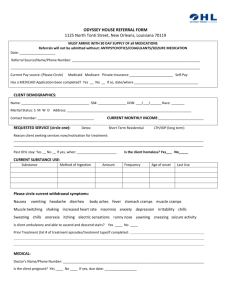

advertisement