Reflection and Physicianship: A Primer for Osler Fellows

advertisement

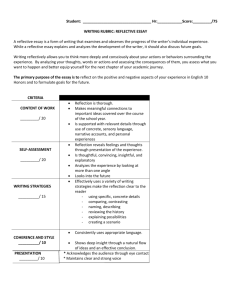

Reflection and Physicianship: A Primer for Osler Fellows “Let us emancipate the student and give him time and opportunity for the cultivation of his mind, so that in his pupilage he shall not be a puppet in the hands of others, but rather a self-relying and reflecting being.” Sir William Osler Executive summary For the purposes of the Physician Apprenticeship (PA), reflection is defined as ‘purposeful attention to both emotional and cognitive aspects of an issue, event or occurrence that, for the learner, is somewhat puzzling, problematic, unsettling or surprising …. uncertain or out of the ordinary’. We recognize two fundamental assumptions: a) that proficiency in reflection is distributed on a spectrum; in other words, some students are highly skilled and open to further engagement while others are either superficial and/or resistant; and b) that, whilst best taught through role-modeling, reflection can also be fostered through the use of structured and planned activities. The relationship between Osler Fellows and their students represents a privileged terrain on which to nurture reflective thinking. Writing exercises, such as journaling, while not the only pathway to self-reflection, have the potential to promote reflection as a ‘habit of the mind’. Our main anticipated outcome in promoting reflection is that it will assist students in understanding and applying the concepts of the physician as healer and professional, in particular, that students will appreciate the central importance of making personal connections to patients (and internalize the notion that the physician has agency in therapy, i.e. ‘the doctor as the pill’). As well, we expect that reflection on beliefs and actions will contribute to an authentic appreciation of the personal transformation (from laymanship to physicianship) that students undergo during a four-year medical school experience. Introduction The Physicianship component of the curriculum has described its expectations of graduates. One of the stated goals is, “We expect our graduates to strive for self-reflection in all phases of the educational continuum and in clinical practice.” Specific objectives that, in theory, relate to self-reflection are: To recognize different types of interactions with team members in medicine and demonstrate awareness of content, context, interlocutor perspectives, self perspectives and one’s own contribution to the situation. To recognize and articulate personal values, biases, strengths and liabilities. To demonstrate respect and openness, in activities (e.g. apprenticeship group discussions) intended to foster insights into the impact of the transition to physicianhood. 1 The nurturing of self-reflection is a key mandate of the PA course. As an Osler Fellow, you will therefore take on the responsibility of promoting it. The purpose of this essay is to assist you in doing so. Definitions Reflection is defined by Boud as: “a generic term for those intellectual and affective activities in which individuals engage to explore their experiences in order to lead to a new understanding and appreciation”.1 It is not simply “mulling things over”. It implies a conscious and deliberate effort to understand and appreciate differently. Some have referred to it as a type of “deep learning”. When focused on cognitive functions, as in problem solving and decision making, it has been called ‘critical thinking’. This narrower, more focused view of reflection - reflective thinking - originates from the American philosopher, John Dewey. It is explicated in his book ‘How we think’.2 Reflection is often tied conceptually to self-assessment. In a recent Medical Education Rounds given at McGill, Dr. Brian Hodges, Director of the Wilson Centre, University of Toronto, described reflection as a “trinity of self-directed [learning], self-reflection and self-assessment”. Other related terms are ‘self-monitoring’, ‘self-knowledge’, and ‘self-awareness’. The term has been used synonymously with mindfulness, introspection, contemplation and even linked to meditation. Self-awareness has been defined as ‘insight into emotional responses in the context of specific situations”.3 It is considered distinct from ‘self-consciousness’ in that the latter may be considered a permanent personality trait. Some (including colleagues at McGill) have argued that, as medical educators, we should not try to modify self-consciousness – a personality trait – but that we should aim to make learners more self-aware. Approximately 30 years ago, Donald Schön proposed the idea of the ‘reflective practitioner’.4 The concept makes a distinction between reflection-in-action, a sort of tacit knowledge that professionals utilize in practice, and reflection-on-action, a reconstructive mental review that occurs following an event or decision. [Note: One can also reflect prior to a specific occurrence; this has been called ‘anticipatory reflection’ or ‘reflection-for-action’.] Although popular in medical education, the idea of the reflective practitioner, particularly the belief that reflection-inaction catalyzes reframing and the development of new ‘meaning schemas’, has been open to debate. The literature suggests that health care professionals engage in reflective practice, that it can be developed through practice and supervision, and that different levels of reflection can be discerned.5 Potential positive outcomes of reflection include increased personal awareness, incorporation of theory into practice, the development of professionalism (e.g. openness to selfregulation), and (perhaps) improved competence. The evidence for the latter claim is thin indeed. Nevertheless, leaders in medical education have adopted the term ‘reflective practitioner’ with gusto; it is now included in the objectives documents of many influential bodies including the Canadian College of Family Physicians and the General Medical Council in the U.K. For the sake of completeness, we would also like to refer to one other related term: ‘reflexivity’. This word is used in the context of qualitative research. It is defined as “the attitude of attending systematically to the context of knowledge construction and it implies that the researcher has 2 called attention to motives, personal background and perspectives as well as preconceptions”.6 The notion of ‘knowledge construction’ is not particularly relevant to PA and we will avoid using the word ‘reflexivity’. The field has become complex and is marked by considerable ambiguity – even with respect to definitions. If you are interested in exploring this further, the article by R. Rogers provides the conceptual basis of reflection in higher education.7 How to teach reflection? An Osler Fellow recently stated, “Reflection is like physical exercise; everyone knows it’s good for you but it is very difficult to do on a regular basis.” The teaching of reflection appears to be equally challenging. It is not good enough to simply tell students: “Go forth and reflect!”. Some consider it misguided to even try and recommend that the school should provide opportunities for reflection along with reasonably good role-models but leave it to the students’ innate abilities or to divine providence or luck to ensure that the skill is acquired. We are not in agreement. Although it is admittedly fraught with challenges, we consider it important for the school to do more than ‘hope for the best’. Students must see that the institution, and the profession in which they are preparing to enter, value this skill. It is also important to emphasize that it is an important component of the ‘McGill clinical method’. The most effective strategy to promote reflection in medical students is probably through rolemodeling and mentoring.8 Effective mentoring must include a balance of providing support and of challenging the mentee. We will explore this during the Osler Fellowship workshops. Without wishing to diminish the importance of role-modeling, this essay will focus on other techniques. The idea of actively coaching students in ‘reflection-in-action’ is very much part of Schön’s approach; to follow his suggestions, teachers should do things such as think out loud, be willing to self-disclose, make oneself vulnerable, and keep a reflective journal that they would then share with students. It is not required of Osler Fellows to do all of the above, but clearly, to teach reflective thinking most effectively implies that the teacher should explicitly display reflection in his/her interactions with patients, students and colleagues. Regardless of the specific methods used to teach or role-model reflection, it is important to understand that reflection involves more than ‘thinking hard and deep’ (as in looking intently into a mirror), even though it is useful to do so. Personal development can be supported and nurtured if one engages in reflective exercises with someone (a colleague, friend, family member, teacher, etc.) or with a group (as in the PA group). An interlocutor other than the ‘inner voice’ can catalyze, encourage and deepen the reflective process. There are a set of questions that are particularly adept at inviting reflection. They are answerable alone or in the presence of a mentor or a peer group. They are applicable to any reflective strategy, method, technique or exercise. Such questions include: What went well? What were you thinking at the time? What were you feeling at the time? What do you think others were feeling? Did any new goals emerge? What did you learn about the problem or issue? What did you learn about yourself? Were any assumptions or preconceptions revealed? Are there things you would do differently the next time around? 3 A set of questions intended to stimulate a conversation with oneself have been developed – these are called Johns’ reflective questions (Appendix A). Another frequently used technique is the use of reflective writing, particularly through the process of maintaining journals or diaries (often called ‘portfolios’).9-11 These are probably more useful in teaching ‘reflection-on-action’ (i.e. after the fact) rather than ‘reflection-in-action’ (i.e. in the ‘thick of things’). Teaching the latter is generally considered to be more difficult. What should one reflect on? Rogers says that, “Reflective processes by their very nature are inductive (beginning with experience) rather than deductive (beginning with textbooks and theories).”6 Medical students should be invited to reflect on any of the following: critical events, personal beliefs and values (especially as these change or evolve through the process of enculturation in the medical profession), patient encounters (especially as they serve to illustrate the pertinence or demonstration of physicianship attributes), interactions with peers, learning goals and needs. The targets of reflection need to be embedded in the activities in which students are involved i.e. the content has to be relevant and meaningful to their lives in the broadest sense and the experiences that are salient to them at any particular time. As such, the focus of reflective exercise will almost certainly be different in the pre-clerkship compared to the clerkship years. Barriers to teaching reflection A significant subset of the student body may be averse to self-awareness activities. Even if this only amounts to 10% of students, given the size of the PA groups, it means that the odds of an Osler Fellow having one of these resistant students in her/his group are still approximately 1 to 2. In addition to there being a spectrum of openness to such activities there is likely to be a range of innate abilities. Some students’ reflective thinking may be less well developed than in others. Additional challenges have been described in the educational literature.12 A few students may be concerned with revealing their inner feelings or deeply held values for fear of rejection or ridicule. Reflective exercises in the context of small groups often require participants to risk being vulnerable. This explains the need for a supportive and safe environment. Invitation to reflect often leads to discussions that have a negative overtone, “on personal distress, oppressive features of the learning environment, the programme of study, assessment practices.”6 Learners and teachers may find the negativity difficult to contain or channel. Some may be uncomfortable with a display of strong emotions; it may result in over-intellectualizing. If students reveal important personal issues, the Osler Fellows must be prepared to deal with them. You must be knowledgeable about where and to whom to refer if ever you feel ‘over your head’. The resources available to you and your students will be discussed. Students have described certain exercises aimed at promoting reflection, particularly the use of portfolios, as ‘busy work’, ‘recipe-following’ or ‘childish’.13,14 If reflection is promoted through the use of journaling, it may be dismissed as a relatively useless or silly ‘paper chase’. As an illustrative example, Memorial University has published on its experience with journaling: “Our initial experience with mandatory journaling was negative in that many students resented being ‘forced to keep a journal’.”15 4 Assessment is also a critical - and thorny - issue. Most Osler Fellows will already be familiar with the adages: ‘Evaluation drives curriculum.’ and ‘Inspect what you expect’. Learners will inevitably come to consider reflection as a low priority if the skill is not subject to an evaluation. This is the case in PA! As soon as students realize that it is not graded, the natural tendency is to make light of it. Having said this, it is important not to be overly cynical or pessimistic. Reflection, and the strategies that schools have implemented to nurture it, do not necessarily have to be evaluated in a summative fashion to be meaningful. They can be considered from the point of view of giving feedback. Although portfolios have been used successfully in formal evaluations in several schools (Groningen University, The Netherlands; Maastricht University, The Netherlands; University of Manchester, U.K.), we have decided to focus on ‘formative assessments’. Conditions that will enhance reflection As noted above, the most influential factors in enabling the development of reflection are probably mentoring and a supportive environment. Other conditions that will assist are: an authentic context, accommodations for differences in learning styles, group discussions, and free expressions of opinion.5 Ronald Epstein, in an essay entitled ‘Mindful Practice’, describes various levels of mindfulness and offers advice as to how it may be achieved.16 The roads to self-awareness There are numerous techniques that can be applied to the task: reflective writing, structured reading exercises, debriefing, vignettes and role plays, and parallel charting. Osler Fellows should feel free to use other strategies that have worked for them in the past. A. Reflective writing Journals are collections of ‘written expressions of thinking’. They can include many genres: narratives, poems, sketches, cartoons, concept maps, music scores, case reports, etc. The Faculty has purchased binders which can be used by students interested in keeping a (Physicianship) diary/portfolio. You will be given these binders at the first faculty development meeting. Please distribute them to your students at one of your first PA group meetings and emphasize that it is a tool to promote reflection. It is recommended that you plan ahead how you will use it. We suggest that you incorporate it into your PA group meetings on a regular basis. Note: An earlier version of the diary was piloted with previous cohorts of students. While there were numerous examples where it was used successfully, the feedback from many students and Osler Fellows was that it was too ‘prescriptive’. We have therefore modified it in order to make it highly flexible. Although its use is considered optional, we are confident that it can be a useful tool for you in nurturing reflection in your PA students. One strategy for working with written materials is that of ‘narrative competence’.17 We will be offering you a workshop where you will be introduced to some if its basic principles and where 5 you will practice applying them to written texts. In short, the underlying theory is that an understanding of narrative structure and its dimensions may provide an entry for deep appreciation of personal values, motives and beliefs. In examining texts (whether they are written or not), it is also sometimes useful to consider the things outside of the text a.k.a. context, pretext (i.e. the legitimation for an activity) and subtext (values which are not normally articulated). Personal texts can be considered a complement to the so-called ‘textbook case’ that students are exposed to – in spades – in the remainder of the curriculum. In any session where written reflections are presented and discussed, it is critical that the environment be non-judgmental and supportive (not unlike that which you provide to your patients in times of stress). A list of questions that can trigger or guide reflective writing is presented in Appendix B. Those that have appeared particularly useful are labeled with a ‘*Recommended’. Please remember that references to specific physicianship attributes (Appendix C) may help in containing and/or channeling negative feelings so as to achieve new understandings and appreciations of stressful or anxiety-provoking situations. B. Structured reading exercises Providing students with texts can provide a specific catalyst for discussion and reflection. Such texts can come from books related to medicine. (See Appendix D.) You can select a chapter from any one of these texts, or from a personal favorite of yours. Several journals (including JAMA and Annals of Internal Medicine) routinely publish illness narratives; these may be useful. Keep in mind the importance of selecting texts that are appropriate for students, e.g. accessibility of language, relevance of context. The literature suggests that the reading exercises should not be too onerous – medical students have many demands placed on them – and that contemporary stories may be more meaningful than the ‘belles-lettres’ classics.19 Once a text is selected, the situation depicted needs to be made meaningful to the student in order to ensure maximum impact from the activity. For example, it may be extremely challenging to establish a connection between a student’s personal and/or professional experiences with a situation of impending death in a palliative care setting. How can you facilitate different understandings of palliative care (and all its implications) if a student has never encountered such a situation? Conversely, a student may have personal experience with the topic and be extremely articulate when sharing thoughts and feelings. Using previously-authored texts as a tool for reflection provides everyone the same starting point to discuss relevant issues. You may ask students to prepare for a group discussion by assigning a specific question, or you may choose to use general questions as a springboard for in-depth discussions. For example, in reading a chapter on palliative care (see textbook by Barnard, et al – the first on the list in Appendix D), you may ask students to respond to the following triggers: 6 “Dr. Towers touches upon the philosophical aspects of euthanasia. How would you feel about exploring the ‘meanings and ramifications’ of euthanasia with a patient who is clearly suffering (p. 92)?” “How would you respond to a family member/caregiver who broaches the topic with you?” You may also choose to ask more general questions to spark discussion, such as: “What were the circumstances of this situation? What ultimately happened? How was the situation addressed? What was learned about (a) the problem and (b) yourself? How would you have addressed the situation?” C. Debriefing During Med 2, you will have an opportunity to view videotapes of your students’ recorded interviews done with standardized patients at the Medical Simulation Centre. This is a good opportunity for you to judge how reflective the students are and to nurture it by asking reflective type of questions. Hatton & Smith have described 4 levels of reflective thinking.20 This framework may be useful to you when, in the context of a debriefing session, you invite students to self-assess: descriptive: is not reflective; it merely reports events with no attempt to provide reasons (e.g. I did x; he said y); descriptive reflection: provides reasons (often based on personal judgment), although only in a reportorial account (I did x because y); dialogic reflection: is a form of discourse with one’s self, mulling over reasons and exploring alternatives (I wonder …? perhaps…?....maybe…..?); and critical reflection: takes account of the sociopolitical context in which events take place and decisions are made (roles, relationships, responsibilities, gender, ethnicity, controllable external factors, etc.). In addition to the model by Hatton & Smith, several other schemas aim to classify levels of reflection and/or propose phases/stages of reflection. Boud speaks about: 1) association; 2) integration; 3) validation; 4) appropriation. Moon uses the following terms: 1) noticing; 2) making sense; 3) making meaning; 4) working with meaning; 5) transformative learning. All of these models – and there are others – have been used in research and teaching. As an Osler Fellow you need not commit to any in particular. The one by Hatton & Smith may be the most accessible. D. Vignettes and role plays It is beyond the scope of this essay to discuss the techniques of role plays or vignettes. The Faculty Development Office can provide you with references or other relevant materials. Two 7 important things to remember are: 1) do not forget to de-brief and 2) use the grid of Physicianship attributes to structure the group discussions that follow the vignette or role play. E. Parallel charting This is a reflective writing exercise of a specific type, done in the context of clinical clerkships. It has been developed by Rita Charon, an internationally-renowned expert in ‘narrative medicine.’21 Charon is an enthusiastic supporter of writing; she has stated, “…to let one’s thoughts achieve the status of language by writing them down is the critical step in making the reflections available for growth”. In her medical school, (Columbia), clerkship students are asked to write, in ordinary everyday language, about the patients they admit, follow and in whose care they participate. They are invited to “consider the patient’s experience of illness and what they themselves undergo in caring for patients”.21 In essence, students are asked to contemplate and write about their inner lives. They do so in a document called the ‘parallel chart’ – parallel, because it is a complement to the patient’s actual and legal hospital chart. Since it is focused on the patient and the student’s response(s) to the patient’s plight, it is not the same as a personal diary, which tends to be much broader in scope. Charon states, “It is indexed to a particular patient” and “It is in the service of that patient’s care”. The students are then invited to read aloud, to a group, from their parallel chart. The techniques of narrative understanding are used to ‘work with’ the chart entries and to help the students achieve a deeper (more reflective) appreciation of their patients, themselves and their unique relationships with patients. Concluding remarks The Faculty feels strongly that the promotion of reflective thinking is important for future medical practice. The literature has demonstrated that journaling accompanied by an open and shared discussion with a group of peers and a mentor can be effective in triggering meaningful reflections. In that spirit, this primer ends with a blank section where you are invited to annotate your own thoughts on the matter and to plan ahead for activities and strategies for triggering reflection in your apprenticeship students. 8 Your personal notes on this primer ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ Your plan of action as to how you will promote reflective thinking in your students ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ 9 ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ 10 APPENDIX A: ‘Johns’ questions’ (designed for ‘conversations’ with the self)18 TOPICS AND PROMPTS DESCRIPTION OF EXPERIENCE Describe the ‘here and now’ experience. What essential factors contributed to this experience? What are the significant background factors to this experience? What are the key processes (for reflection) in this experience? REFLECTION What was I trying to achieve? Why did I intervene as I did? What were the consequences of my action for: myself? The patient/family? For the people I work with? How did I feel about this experience when it was happening? How did the patient feel about it? How do I know how the patient felt about it? INFLUENCING FACTORS What internal factors influenced my decision making? What external factors influenced my decision making? What sources of knowledge did/should have influenced my decision making? ALTERNATIVE ACTIONS What other choice did I have? What would be the consequences of these choices? LEARNING How do I now feel about this experience? How have I made sense of this experience in the light of past experiences and future practice? How has this experience changed my ways of knowing: empirics? aesthetics? ethics? personal? 11 APPENDIX B: Trigger activities or questions CORE CLERKSHIPS MED 1 REFLECTIVE WRITING: ACTIVITIES Ask your students to write a memo to themselves where they speak of fears or hopes at this important transition point in their lives. Recommend that they place this ‘personal memo’ in a sealed envelope. Inform them that you may invite them to share it at the farewell PA meeting in 4th year (i.e. just before graduation). *Recommended A reflection on the cadaver dissection: What was it like when you first ‘met’ your cadaver? Did you have perceive any hints as to who that person was before death?... What they did in life? ….How they lived? These trigger questions can lead to a group discussion and/or diary entries. *Recommended Ask, “Have you ever …” type of questions. Example: “Have you ever seen a morbidly obese patient and thought s/he was lazy?” or “Have you ever heard someone who is a smoker complain about a cough; How did it make you feel?” These aim to acknowledge and confront prejudices about race, gender, religion, culture, substance use, sexual orientation, elderly, disabled, other professions, etc. Request a written response to the question, “How is professionalism different for a medical student as opposed to a practicing doctor?” Ask your students to write about a healing moment that was experienced or observed or to describe a situation where an opportunity to provide one was missed. Follow this with a group discussion. *Recommended Ask your students to describe a situation where they were able to demonstrate empathy or where they felt blocked from demonstrating empathy. Follow this with a group discussion. *Recommended Invite your students to share any of the following: cards or gifts given by families; reading an obituary about a patient in whose care they were involved; a song or poem they were compelled to compose recently; their reactions at a recent movie or with a novel where issues related to sickness arose. Ask your students to reflect on how a particular clinical encounter influenced their career decision-making process: “What aspect of it turned you ‘on’ or ‘off’ that discipline?” Invite a student to discuss reactions to a clerkship evaluation which they considered unjustified (either too critical or too laudatory). Note: Please do this in a one-on-one situation with a student rather than in a PA group meeting. Ask students to consider how their experiences have contributed to the ongoing development of their identity as a physician. You may ask them whether or not these experiences have helped promote or demote this emerging identity. 12 AT ANY TIME REFLECTIVE WRITING: ACTIVITIES Ask your students to describe a situation where they felt ridiculed or diminished. Follow with a group discussion. *Recommended Ask your students to describe a situation where they became frustrated or lost their temper or composure. Follow with a discussion; it could be in a group setting or one-on-one. *Recommended Invite students to share moments from medical school that ‘surprised’ them. This could include both positive and negative examples. Instruct students to reflect upon the following questions when keeping in mind their example: What were the circumstances of this situation? What ultimately happened? How was the situation addressed? What was learned about (a) the problem and (b) yourself? What would you do differently in the future? *Recommended In order to highlight positive experiences which occur during medical school, ask students to write about a ‘victory’ they have had in clinical contexts. *Recommended Ask students to describe a patient encounter in the following manner: (a) Before the encounter, what was your goal for meeting the patient? (b) Were you motivated for the encounter? Please describe. (c) What key information did you take away from the encounter? How did you learn this? (d) What type of external feedback did you receive, and from who? What type of internal feedback did you provide for yourself? (e) What could you have done differently to maximize your learning and performance? *Recommended Ask students to reflect on the relationships that form during their medical education: Have these relationships been positive or negative? Describe one of each, and explain how they made you feel and impacted on your work. Note: As with most of these triggers, discretion is required. It is often wise, particularly in group settings, to avoid naming individuals, whether fellow students, academic or non-academic staff. Ask your students to describe an unexpected reaction (e.g., fainting in the operating room, disgust). Follow with a group discussion. Ask students to respond to the question: What features of my personality do I want to be more evident to the patients for whom I will have responsibilities? Ask for a reflection on a positive or negative role model. Explore the interpersonal skills and/or levels of mindfulness that were demonstrated. Invite students to update their autobiographical letter. Just prior to graduation, it may useful to ask them to specifically address how they intend to contribute to social justice in their career. Explore any critical incident that may have occurred (e.g. having made a mistake, faced an ethical dilemma). Such incidents are particularly ripe for the exploration of values, motives and beliefs. Ask students to describe an event illustrating positive and/or negative rolemodeling of one or more of the following professional attributes: altruism, commitment, self-regulation, honesty or integrity. 13 APPENDIX C: Attributes of the healer and professional roles ATTRIBUTES AND DEFINITIONS Professional and Healer Professional Self-regulation: the privilege of setting standards; being accountable for one’s actions and conduct in medical practice and for the conduct of one’s colleagues. Responsibility to society: the obligation to use one’s expertise for, and to be accountable to, society for those actions, both personal and of the profession, which relate to the public good. Responsibility to the profession: the commitment to maintain the integrity of the moral and collegial nature of the profession and to be accountable for one’s conduct Team work: the ability to recognize and respect the expertise of others and work with them in the patient’s best interest. Competence: to master and keep current the knowledge and skills relevant to medical practice. Commitment: to be obligated or emotionally impelled to act in the best interest of the patient. Confidentiality: to not divulge patient information without just cause. Autonomy: the physician’s freedom to make independent decisions in the best interest of patients and for the good of society. Altruism: the unselfish regard for, or devotion to, the welfare of others. Trustworthiness: worthy of trust, reliable. Integrity and honesty: firm adherence to a code of moral values; incorruptibility. Caring and compassion: a sympathetic consciousness of another’s distress together with a desire to alleviate it. Healer Insight: the ability to recognize and understand one’s actions, motivations and emotions. Openness: the willingness to hear, accept, and deal with the views of others without reserve or pretense. Respect for the healing function: the ability to recognize, elicit, and foster the power to heal inherent in each patient. Respect for patient dignity and autonomy: the commitment to respect and ensure subjective well-being and sense of worth in the patient and recognize the patient’s personal freedom of choice and right to participate fully in his or her own care. Presence: to be fully present for a patient without distraction and to fully support and accompany the patient throughout care. 14 APPENDIX D: List of options for structured reading exercises BOOKS AND BOOK CHAPTERS Barnard C, Towers A, Boston P, Lambrinidou Y. Crossing over: Narratives of palliative care. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. Davidoff F. Who has seen a blood sugar? (Reflections on medical education). Philadelphia: American College of Physicians; 1996. Gawande A. Complications (A surgeon’s notes on an imperfect science). New York: Picador; 2003. Jauhar S. Intern (A doctor’s initiation). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2009. Klass, P. A not entirely benign procedure (Four years as a medical student). New York: Plume; 1987. Klass P. Treatment kind and fair: Letters to a young doctor. New York: Basic Books; 2008. Konner M. Becoming a doctor (A journey of initiation in medical school). New York: Penguin; 1988. Lam V. Bloodletting & miraculous cures. Toronto: Anchor Canada; 2006. Lowenstein J, Markel H, Stern AM. The midnight meal and other essays about doctors, patients and medicine. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 2005. McCarthy C. Learning how the heart beats (The making of a pediatrician). New York: Viking; 1997. Rothman EL, Rothman E. White coat (Becoming a doctor at Harvard Medical School). New York: Harper; 2000. Selzer R. The doctor stories. New York: Picador; 1998. See also reference #18 for another list as well as the Physicianship website: http://www.medicine.mcgill.ca/physicianship/Oslerfellowship_Resources.htm 15 Bibliography 1. Boud D, Keogh R, Walker D. Reflection: turning experience into learning. Kogan Page London, 1985 (eds). 2. Dewy J. How we think. New York: Prometheus Books. 1991. 3. Benbassat J, Baumal R. Enhancing self-awareness in medical students: an overview of teaching approaches. Acad Med 2005;80:156-161. 4. Donald Schön. The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books. 1983. 5. Mann K, Gordon J, MacLeod A. Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review. Adv in Health Sci Educ .2007 (published online Nov 23, 2007). 6. Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet 2001; 358:483-488 7. Rogers R. Reflection in higher education: a concept analysis. Innovative Higher Education. 2001;26:37-57. 8. Kenny N, Mann K, MacLeod H. Role modeling in physicians’ professional formation: reconsidering an essential but untapped educational strategy. Acad Med 2003;78:12031210. 9. Shapiro J et al. Words and wards: a model of reflective writing and its uses in medical education. J Med Humanities 2006;27:231-244. 10. Brady DW. What’s important to you? The use of narratives to promote self-reflection and to understand the experiences of medical residents. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:220-223. 11. Driessen EW, et al. Conditions for successful reflective use of portfolios in undergraduate medical education. Med Ed. 2005;39:1230-1235. 12. Boud, D. and Walker, D. Promoting reflection in professional courses: the challenge of context. In R. Harrison, F. Reeve, A. Hanson and J. Clarke. 2002 (eds.) Supporting Lifelong Learning. Vol. 1. Perspectives on learning. London UK: Routledge Farmer. (pp. 91-110). 13. Driessen EW, et al. Portfolios in medical education: why they meet with mixed success? A systematic review. Med Ed 2007;41:1224-1233. 14. Kalet AL. et al. Promoting professionalism through an online professional development portfolio: successes, joys and frustrations. Acad Med 2007; 82:1065-1072. 15. Pullman D, Bethune C, Duke P. Narrative means to humanistic ends. Teach Learn Med 2001;17:279-284. 16. Epstein R. Mindful Practice. JAMA 1999;282:833-839. 17. Charon R. Narrative Medicine: A model for empathy, reflection, profession and trust. JAMA 2001;286:1897-1902. 18. Baernstein A, Fryer-Edwards K. Promoting reflection on professionalism: A comparison trial of educational interventions for medical students. Acad Med 2003;78:742-747. 19. Weisberg M, Duffin J. Evoking the moral imagination: using stories to teach ethics and professionalism to nursing, medical and law students. J Med Human 1995:16:247-263 20. In: Pee B, et al. Appraising and assessing reflection in students’ writing on a structured worksheet. Med Ed. 2002;36:575-585. 21. Charon R. Narrative Medicine: Honoring the stories of illness. (Chapter 8: The parallel chart). Oxford University Press. 2006. 16