MINISTÈRE DES AFFAIRES ÉTRANGÈRES ET EUROPEENNES A

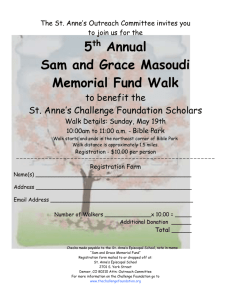

advertisement

MINISTÈRE DES AFFAIRES ÉTRANGÈRES ET EUROPEENNES N° 8 – April 2010 Anne Dejean-Assémat, distinguished French scientist A biologist specialising in the mechanisms that cause cancer in humans, Anne Dejean-Assémat has just been awarded the L'Oréal-Unesco prize for women in science, worth $100,000, in recognition of many years of research. Anne Dejean-Assémat likes to run in the Paris parks in all weathers, like a true fighter. And it’s not by chance that the characteristics of the marathon runner – a regular stride and perseverance in the face of an unrewarding nature and the weariness of all that effort – are cultivated by the tall blonde scientist. These are the qualities that have earned Anne Dejean-Assémat the prestigious L'Oréal-Unesco prize for women in science. Each year, five female researchers from across the world are awarded the prize, not only for the exceptional importance of their work but also Anne Dejean-Assémat © photo Micheline Pelletier for the L'Oréal Corporate Foundation because, according to the 18 members of the judging panel led by Günter Blobel, who won the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1999, they act as role models for girls who want to take up a scientific career. Fighting cancer Anne Dejean-Assémat has a doctorate in science and since 2003 has led the Cellular Organisation and Oncogenesis unit at the Institut Pasteur and the Molecular and Cellular Biology of Tumours unit at Inserm - the French National Institute for Health and Medical Research. Every morning, when she puts on her white coat, she gets ready to understand the mechanisms by which cancer works in order to develop better ways of treating it. The disease starts with healthy cells which are transformed and then become cancerous. The reasons for their transformation are still not properly understood and this is the mystery that Anne Dejean-Assémat is trying to unravel. It means spending hours at a time bent over a laboratory microscope, exploring the infinitely small world of the human cell. Almost all of a cell's genetic content is in its nucleus. This contains the proteins that serve as “receptors" for small molecules such as vitamins or hormones. Anne Dejean-Assémat discovered that one of these receptors, for retinoic acid, was structurally different in the cancerous cells of patients with leukaemia. At last, an explanation of how a mutation in this receptor could lead to leukaemia in patients. This discovery represents a huge step forward in the possible therapeutic effect of retinoic acid in this type of leukaemia. But how many hours of work did it take to achieve this result? “This job is mostly about failure,” she points out. “You can’t afford to have too great a sense of self-importance and you need DIRECTION DE LA COMMUNICATION ET DU PORTE-PAROLAT SOUS DIRECTION DE LA COMMUNICATION MINISTÈRE DES AFFAIRES ÉTRANGÈRES ET EUROPEENNES to be made of pretty stern stuff. You only get the result you hoped for from an experiment about once every two years.” Remarkable progress in therapies Such dry spells do not deter the researcher when she is heading in such a positive direction. She points out that the same receptor also alters in some cancers of the liver and she has shown that hepatitis B may be the cause of the mutation. This is a significant step forward, because it proves a direct link between a viral infection and a healthy cell turning into a cancerous one. Yet more recently, the researcher proved that arsenic, a substance used in the treatment of certain leukaemias, also has the ability to alter a mutated retinoic acid receptor. The use of arsenic to counter the mutation therefore becomes an interesting avenue to explore. Her current work is focusing on the SUMO protein, discovered in the 1990s, which can also alter the structure of the mutated retinoic acid receptor. The question is now to understand how changes in the activity of the protein can cause abnormal cell division and cancer. Balancing research and private life A member of the French Academy of Sciences since 2004, Anne Dejean-Assémat is well aware that she is able to carry out her painstaking work thanks, in part, to the understanding of those around her. Her husband, first of all, an indefatigable supporter, and her three children, two girls and a boy, now in their late teens. Even at home, “you don’t leave your projects behind when you shut the laboratory door,” she insists. “I think about my work all the time.” It may be a complex formula, but balancing family life and the work of a top-level scientist is not impossible. Although these days it is her family that keeps things going on the home front and provides a haven where she can unwind, it was her parents, an engineer and a mathematics teacher, along with a biology teacher at her secondary school, who inspired and motivated her to take up a career in science. “I was fascinated by the plant and animal kingdoms,” she says. “It seemed to me that spending my life trying to understand them would be a joy. It’s still a privilege rather than a duty for me to go to the laboratory every morning.” Another element that sparked off her chosen career was her parents’ militantism. Her father, a passionate ecologist, and her feminist mother taught her to challenge and question received ideas relentlessly. This has proved a real advantage in her daily work. Gender equality on the move Clearly fulfilled by her career, she now encourages girls to take up a career in science without hesitation: “If you love this job, forget your reservations and grasp the opportunities!” she cries. The biologist understands the fear girls may have of not being able to achieve a balance between an intense professional life and their private life, but she adds, “attitudes need to change. We need to encourage and reassure girls from a very young age. We need to have faith in women.” Anne Dejean-Assémat remembers her early days at scientific conferences, often the only woman in a room full of men, so she is delighted that gender equality is becoming the order of the day even in the scientific community. The proof? The women who received the Nobel prizes for biology and medicine in 2009. Two of them had also previously been awarded the L’Oreal-Unesco Foundation prize. Pascale Bernard DIRECTION DE LA COMMUNICATION ET DU PORTE-PAROLAT SOUS DIRECTION DE LA COMMUNICATION