File

Title: Questioning Strategies - Using Thick and Thin Questions for Comprehension

Objective

The students will be able use Thick and Thin Questioning in order to comprehend information provided in the text and on a map of the Ancient River Valley Civilizations.

Standards

PA Standards Aligned System – Reading Comprehension

R8.A.2.3.1: Make inferences and/or draw conclusions based on information from text.

PA Common Core Standards – Reading in History and Social Studies

8.5 Reading Informational Text: Students read, understand, and respond to informational text – with emphasis on comprehension, making connections among ideas and between texts with focus on textual evidence o CC.8.5.6-8.G. Integrate visual information (e.g., in charts, graphs, photographs, videos, or maps) with other information in print and digital texts.

Anticipatory Set

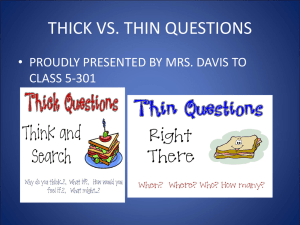

Class, looking at the map in front of you, what continent is this map showing? Accept an answer from the class – (Asia). Great, now, what is the title or theme of this map?

Accept answers from the class – (Early Civilizations). Good! Now, more specifically, how many early civilizations are featured on this map? Call on a student to answer

(Four). Excellent, now how did you know the answers to all of my questions? Accept a few answers from the class. Students should arrive at the conclusion that they know the answers because they are right in front of them on the map – clearly spelled out. Those

were some good ideas. The answers to the questions I asked you were right in front of you. They were facts that you could easily gather by looking at the map or at the text.

So, for example, when I asked you how many early civilizations this map featured, you could see in the key that there were four civilizations labeled. These types of questions are known as thin questions. Thin questions are questions that are factual and the answered by looking in the text. Now, knowing that these are called thin questions, what might the opposite types of questions be called? Accept a few answers from the class, and then clarify. Great! An antonym for thin would be thick! The other type of question is called a thick question. Let me give you an example of a thick question and see if you can figure out how to answer it. “Looking at the map, why do you think these four civilizations formed in their specific locations?”

Allow students adequate processing and response time. Accept a few answers from the class. Great! You’ve noticed that these civilizations formed along rivers. How did you come to this conclusion? Did it say it in the text? (No) Please explain your thought process. Answers may vary. Thought processes should be along the lines of: the students could see a river running through each of the civilizations; the civilizations names include the word “River” which is located in the key; students used prior knowledge from class discussions to make a connection with the idea that all civilizations need a water source, etc.

Great! Does anyone know what this skill is called? Using the information given, context clues, pictures, and background knowledge to read a conclusion? It’s making an inference!

You need to make inferences and use higher order thinking in order to answer thick questions.

Procedure

Introduction

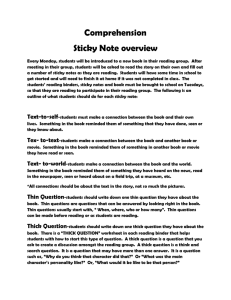

Today we are going to use thick and thin questioning to help us comprehend informational texts. We are going to practice creating our own thick and thin questions, using the information provided to us in the text. Creating your own questions will not only give you practice with thick and thin questions, but it will also help you to understand how the information is connected. Pass out the Thick and Thin Questioning

Handout for students as a graphic organizer outlining the differences between the two and providing sentence starter examples. Many of the questions you see day to day are what we call thin questions. They test your basic knowledge and memorization of the facts.

Thick questions will challenge you to explore various levels of comprehension, and will call for you to make connections and inferences. Take a look over this handout so that you are able to know the difference!

Modeling

Now that we know what thick and thin questions are and how they will help us understand what we read; I'll model how you should use this strategy. I'm going to use a previous section of the text, England – Stonehenge, which we have already read to model this strategy. I'm going to read you a passage from the text; please follow along with me.

"Construction on Stonehenge began around 3100 B.C.E., when the British Isles were in the Bronze Age. Archaeologists assume that the stone circles have religious significance. Most archaeologists agree that the placement of the stones reflects solar and lunar movements. Given that Stonehenge is on a plain 20 miles from the hills where they were quarried, it must have taken considerable effort and skill to drag and then lift the stones into place.

At one time it was widely believed that Stonehenge was a Druid temple.

Stonehenge remains the site of Druid rituals by small groups of followers of the ancient Celtic religion. The Altar Stone was so named because the Druids performed animal and human sacrifices. Formerly open to visitors who could

wander among the stones, Stonehenge is now fenced off to protect the national treasure.”

Now, I’m going to look in this passage and create two thin questions based on factual evidence, and one thick question that would cause the reader in infer.

Let’s start with the thin questions:

1.

What is the significance of the placement of the stones?

What would make this a thin question? Accept answers from students. (The answer is plainly laid out in the text. You can see the information right in front of you). Great! These are all reasons that I know this would be a thin question.

What would our answer to this question be? Archaeologists assume that the stone circles have religious significance, and most agree that the placement of the stones reflects solar and lunar movements.

Excellent! Let’s make one more.

2.

What are the theories about who built Stonehenge and why?

Now, how do we know this question is a thin question? Accept answers from students. Answers will vary but will resemble those from the previous question.

Good, let’s answer this question, too.

It was at one time widely believed that

Stonehenge was built by the Druids. The Druids worshiped the sun, and because most archaeologists believe that the placement of the stones reflects solar and lunar movements, many have assumed that the Druids must have been responsible for building Stonehenge.

Okay, now that you’ve seen me create two thin questions, I’m going to show you how to create a thick question. Let’s look over the text again. It says here “that

Stonehenge is on a plain 20 miles from the hills where they were quarried, it must have taken considerable effort and skill to drag and then lift the stones into place.” Now, so if I asked a question that said something like:

3.

How do you think the stones were transported to the site and raised to an upright position?

Would you be able to answer this? Let’s try.

Answers to the thick question will vary, but most students will probably suggest that the stones were dragged to the site, using huge numbers of animals or men. Some students may suggest that the stones were floated down rivers on rafts to the site. It may be suggested that men used a man-powered mechanical contraption such as a rope and pulley to bring the stones to an upright position.

Those were some great answers.

How did you come to those conclusions? Did it spell it out for you in the text? No. You made inferences! You used the information from the text, you used the pictures of Stonehenge, and you used your background knowledge to come to these conclusions! This is an example of a thick question.

Guided Practice

Now I’m going to read another section of the text about the development of

The

Lascaux Cave Paintings in France . Again, please make sure you are following along.

"The Cave of Lascaux was re-discovered in 1940 by four teenagers and their dog in southwestern France, about 17,000 years after its interior was decorated by

Paleolithic artists. When mapped, the caves look like interconnected tunnels.

The animal images range from horses, bison, ibex, aurochs (an extinct type of ox), stags, mammoths, reindeer, bears, felines, rhinoceros, birds, and fish. The images are notable for their technical mastery, but unfortunately their significance is not known.”

Now what kind of thin questions would you make from that passage? Have the students raise their hands and give suggestions. Good, you all made some great thin questions. Some thin questions I would ask from that passage are:

1.

How was the Lascaux Cave re-discovered?

2.

What types of animals are depicted in the drawings?

3.

What is the layout of the cave?

These are great thin questions to ask because they are easily identified in the text.

You can point to your answer to prove that it is correct. Can you do that to answer these questions? Give it a try. Allow students to search through the text and point out where the answers to these questions can be found.

Now we are going to create a thick question together. I will read the passage again, and then you can tell me some thick questions that could be made from it. Once again, follow along! Read the passage over again slowly so that students can make the connections and inferences necessary to create a thick level question.

Okay, let’s see what you can come up with! Allow students to give suggestions of thick questions and ask them to explain their thought process behind creating each question. Allow other students the opportunity to answer one another’s example thick

questions. Great! Those were wonderful examples of thick questions that would cause us to infer, make connections, and use our background knowledge referring to the passage.

The thick question that I would make is:

1.

Why do you think this art work was created?

Can anyone give an answer to that? Allow students to answer the question. Ask them to explain their thought process and how they came to their conclusions. Great job!

All of your answers required you to use higher order thinking to come to your conclusions! That is what makes this question a thick question.

Independent Practice

Now that I’ve modeled thick and thin questioning strategies for you, and you’ve had some practice with it; you are going to work independently and make your own thick and thin questions using the next section of the text on Early Civilizations.

This section consists of three paragraphs. You will need to create two thin questions and one thick question per paragraph. Look for factual information that you can make into thin questions; underline these facts. When you come across something that you think is an inference, highlight it for when you go to make your thick questions. When you have completed your questions – nine in all – you will exchange them with the person next you.

You will answer one another’s questions and then check your work with the text. Use your handout from earlier for examples and sentence starters, and I will be around to help you.

1.5 Differentiation:

This questioning strategy supports students reading development because it helps them understand that when reading informational texts you need to use the clues in the text to come to a conclusion. When students are creating their own questions, they are focusing on these clues and making inferences at the same time. For English Language learners, the text is available on tape for them to listen to at their own pace. This way, students are not focusing on decoding the language of the texts, but more so on the content and information needed for comprehension. Chunking of the assignment by paragraph or modifying the number of required questions can also be useful for students who are struggling with the concept. Gifted students would be encouraged to work with one another, allowing them to create more difficult questions, and provide lengthier answers. If students continue to struggle, I suggest going back and modeling the strategy with a different text, preferably one that they are familiar with. The chosen texts are curriculum-based texts, outlining content information on Early Civilizations; however this strategy can be done on any informational text.

Closure:

Have the students raise their hands when they are finished. I will go around the room and check the student’s questions and partnered answers. What did you find most difficult about making thin questions? Thick questions? Accept a few answers.

What did you find easiest about making thin questions? Thick questions? Accept a few answers. What did you learn about making questions as a way to understand the text? Accept a few answers. How did making up your own questions help you understand the text better?

Accept a few answers . I hope this helped everyone

understand Early Civilizations. I encourage you to use this questioning strategy with every informational text that you read. Today we learned that making up our own questions, thick and thin to be exact, helps us understand the text better. We will be using thick and thin questioning several times throughout the year when we are reading important information. Next week we will be making thick and thin questions on the section about Archeological Digs.

1.1

Assessment

Formative: I will assess the students through observation. I will observe whether or not the students are able to create questions and provide answers during the guided practice.

Summative: During the independent practice, I will check students’ work to monitor their progress during the questioning process. I will use the follow up questions to see what the students found easiest and hardest when creating thick and thin questioning in terms of comprehension.

Materials

Textbook – Cicero World History A – Early Civilizations to the Mid-1800s

Passages from Chapter 1: England – Stonehenge, The Lascaux Cave

Paintings, Early Civilizations

Early Civilizations Map

Worksheet – Thick and Thin Questioning Handout

Writing Utensils

Passages from Cicero World History A – Early Civilizations to

the Mid-1800s:

England – Stonehenge

"Construction on Stonehenge began around 3100 B.C.E., when the British Isles were in the Bronze Age. Archaeologists assume that the stone circles have religious significance. Most archaeologists agree that the placement of the stones reflects solar and lunar movements. Given that Stonehenge is on a plain 20 miles from the hills where they were quarried, it must have taken considerable effort and skill to drag and then lift the stones into place.

At one time it was widely believed that Stonehenge was a Druid temple.

Stonehenge remains the site of Druid rituals by small groups of followers of the ancient Celtic religion. The Altar Stone was so named because the Druids performed animal and human sacrifices. Formerly open to visitors who could wander among the stones, Stonehenge is now fenced off to protect the national treasure.”

The Lascaux Cave Paintings

"The Cave of Lascaux was re-discovered in 1940 by four teenagers and their dog in southwestern France, about 17,000 years after its interior was decorated by

Paleolithic artists. When mapped, the caves look like interconnected tunnels.

The animal images range from horses, bison, ibex, aurochs (an extinct type of ox), stags, mammoths, reindeer, bears, felines, rhinoceros, birds, and fish. The images are notable for their technical mastery, but unfortunately their significance is not known.”

Early Civilizations

“The map shows the location of four original civilizations. Later civilizations that developed in other parts of Asia, Africa, and Europe were influenced by the four original civilizations through trade or conquest. Civilization refers to a relatively high level of cultural and technological development. Specifically it refers to the stage of cultural development at which writing and the keeping of written records is attained.

All four of the original civilizations developed in river valleys. Climatic changes at the end of the last ice age altered the land in prehistoric times. At about the same time, some bands of humans were becoming Neolithic people who domesticated animals and planted crops. As the climate became drier, Neolithic people moved into river valleys where they learned to irrigate the land to nourish their crops. Setting up irrigation systems required settled communities, rules, and a government. Writing developed as a way to keep records of crops and of land boundaries, which might get erased during floods.

The earliest civilizations were in Egypt (along the Nile River) and in

Mesopotamia (between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers). Neolithic people were living in settlements along the rivers long before 4000 B.C.E. In Mesopotamia,

Sumerian city-states grew in size and sophistication. By 3400 B.C.E. cuneiform writing, which involved impressing symbols into tablets of wet clay with a stylus and baking the clay to preserve them, was in use. About the same time hieroglyphics were being used in Egypt. Hieroglyphics were inscribed on a form of paper made from papyrus plants. Writing evolved in China before 2000 B.C.E. during the Shang culture, which developed along the Huang He (Yellow) River.

All three forms of writing used symbols for objects and ideas. The concept of using symbols for sounds developed later. Less is known about the civilization in the Indus River Valley of India. Centered in the cities of Harappa and Mohenjo-

Daro around 2500 B.C.E., it lasted less than a thousand years. The Indus Valley civilization did, however, have contact with Mesopotamian civilizations.”

Cicero – World History A – Early Civilizations to the Mid-1800s:

Map of Early Civilizations