The Effectiveness of Play as an Instructional Strategy on Procedural

The Effectiveness of Play as an Instructional Strategy on Procedural

Learning, Learner Enjoyment, and Instructional Design

Susan Codone, Ph.D.

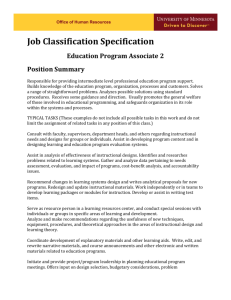

Manager, Interactive Multimedia Production

Raytheon Interactive Technologies

600 University Office Blvd, Suite 6

Pensacola, FL 32504

850-476-1750 ext 694 fax: 850-474-4807

scodone@raytheonpns.com

The Effectiveness of Play as an Instructional Strategy on Procedural Learning, Learner

Enjoyment, and Instructional Design

This paper presents findings of a 1999-2000 dissertation study into the nature of play and its appropriateness as an instructional strategy for procedural learning outcomes. The study has two research questions. First, the study sought to identify the indicators of play from student, instructor, and designer perspectives. Second, the study investigated play as an instructional strategy and questioned how play affects enjoyment and emotion. Results are presented and discussed.

The W-I-R-E Model of Play is presented as a strategy to be used by instructional designers to embed play into instruction more effectively.

2

The Effectiveness of Play as an Instructional Strategy on Procedural Learning, Learner

Enjoyment, and Instructional Design

Introduction

As a psychological construct and a method of learning activity, play has received much attention over the years, but not a great deal of focused, investigative research. For this study, play was defined as a phenomenon crossing both cognitive and behavioral lines that can be stimulated by events or environmental effects. For play to occur in an instructional environment, the following conditional characteristics should be present: surprisingness, novelty, incongruence, randomness, suspension of reality, and variety (Levy, 1996).

In children, play has been studied to determine its composition -- its characteristics and components, along with its meaning for childhood development. Yet there is a research void that becomes larger as we approach adulthood. In adults, play has been studied as recreation and leisure, but not as a serious method of learning. There is a critical lack of research into the impact of play upon learning, especially in adults.

An emerging critical issue is the cognitive and affective impact of play in adult learning, specifically within interactive multimedia instruction and other forms of electronic and virtual training (Rieber, 1998). Distinct from gaming, as in video or computer games, which are ruledriven and goal-oriented, the inclusion of play within interactive multimedia can be open, voluntary, pleasurable, and non-goal oriented. Technology-based play can also be elaborative and promote deeper processing by serving as an exploratory and investigative device. As the world moves to be more dependent upon the Internet for information and learning purposes and as adults allocate more leisure time to their computers, the importance of studying technologybased play becomes increasingly critical.

3

Instructional research recommends strategies for technology-based learning that do not typically include prescriptions for play. In fact, instructional strategies that are particularly effective with adult learners continue to evolve both in definition and application. Gagne,

Briggs, & Wager (1992), Jonassen (1996), and Merrill (1996) have written volumes of scholarly works specifying hierarchies of instructional strategies and tactics to be used with differing types of content but none include specifications regarding play. Berlyne (1968) describes the perplexing and arduous task of attempting to compile a list of the most salient characteristics of play and states that a characterization of playful behavior is not easy.

Given these research gaps, this study was undertaken to explore the impact of play on adult learning and the possibilities of play as a viable instructional design strategy. The hypothesis was that if play characteristics are present, then the instructional environment would effectively stimulate play in the learners and influence the learning of the desired outcome through play. The ultimate goal of the study was to begin to understand the indicators of play from student, instructor, and designer perspectives and to apply those indicators to instructional design specifications for interactive multimedia learning.

Two research questions framed this study. First, what are the indicators of play, and how do indicators differ between student, instructor, and practitioner perspectives? Second, the study asked how play can be used as a viable instructional strategy to accomplish the outcome of procedural learning.

Perspectives and Theoretical Framework

Educational and psychological literature is rich with expository and rhetorical descriptions of play, but weak regarding measurable studies of the effectiveness of play in learning. A

4

review of the literature uncovered a rich repository of data regarding play as childhood and adult activity but was incomplete concerning play relating to learning.

Defining Characteristics of Play

Play is a psychological construct that subsumes a variety of human behaviors and thus has received a great deal of attention in the last 30 years. Emerging from a perspective that originally emphasized social adaptation as an effect of play in Montessori's writings in the early

19th century and as an expression of primary needs in Freud's writing in the early twentieth century, play has become connected to many other psychological constructs, such as language formation, symbolism, abstraction of intellectual prototypes, acquisition of tool use, social skill development, perspective or role taking, and the development of creativity (Sutton-Smith, 1979;

Christie & Johnsen, 1983).

As an abstract concept, play is sufficiently rich and ambiguous to effectively link to these constructs and many more; however, a consensual, operational definition of play continues to elude researchers in the fields of psychology, anthropology, education, and sociology (Lentz,

1982, Levy, 1978). Lentz summarizes this dilemma neatly by saying, "We seem to intuitively know what play is, but we still have difficulty defining exactly what factors are involved in the play process" (p. 68). F.A. Beach was one of the earliest to study play behavior in the animal kingdom and make play generalizations to humans. Regarding the lack of understanding of play,

Beach stated:

On the other hand stands our undeniable ignorance as to the essential nature of play, its causes and its results. The richness of observational evidence is in sharp contrast to the poverty of scientific knowledge . . . . The majority of interpretations purporting to define

5

or explain play are speculative in nature, deductively derived, and completely untested.

(Beach, 1945, p. 523, 527)

In 1971, Herron and Sutton-Smith stated that the study of child’s play has attracted the attention of researchers from many fields, including anthropology, biology, child development, education, psychology, psychiatry, recreation, and sociology. Yet despite the magnitude of concentration on play, it has never been an organized focus of scientific attention or sustained research. Levy (1978), in his recommendation to employ the scientific method to the study of play, describes the research of play behavior up to the 1970’s as being meager and devoid of traditional scientific approaches such as those used in the physical sciences.

Despite difficulties of definition, many researchers have managed to summarize the common characteristics that are present in most definitions of play and form the core of an emerging theoretical stance on the role of play in graduated levels of development. Johann

Huizinga (1951) defined play as a “ . . . free activity standing quite consciously outside ‘ordinary’ life as being ‘not serious,’ but at the same time absorbing the player intensely and utterly.”

(p. 13). Christie and Johnsen (1983) state that cognitive, social, and psychomotor behaviors that constitute play should have the following characteristics: (a) behavior which is intrinsically motivated, spontaneous, and self-generated; (b) behavior which is pleasurable or connected with positive affect expressed in the absence of highly anxious conditions -- play is not serious; (c) behavior that varies individually and situationally -- play is flexible; and (d) behavior that is not literal or that expresses an element of pretense and fantasy. Isenberg & Quisenberry (1988) add that play should be process-oriented, exploratory, and active. Frost (1992) agrees with Christie and Johnsen by describing play as an activity that is pleasurable, voluntary, spontaneous, devoid

6

of imposed tasks or regulations, intrinsically motivated, undertaken for process rather than expected outcomes, and that requires active participation.

Behaviorist Influences on Play

Tenets of the behaviorist movement of educational psychology restricted the value of play. Singer (1995) explains the impact of stimulus-response reductionism on psychology, particularly on play. Behaviorists contend that since children's play did not provide immediate benefits in learning that were easily observable or measurable, their energies were directed toward drill and practice exercises rather than playful, constructive effort.

Developmental Influences on Play

Singer writes that the early part of the twentieth century was characterized by the biologically based motivational systems of the type fostered by Sigmund Freud in the last 30 years of his life and that play was perceived as largely an effort by children to deal with early conflicts about psychosexual impulses. According to Singer (1995) and Cheska (1978), Freud believed that children at play re-enact situations that they wish to master in order to deal with prior tensions and conflicts. Singer described further that the independent research of Kurt Lewin, Lev

Vygotsky, and Jean Piaget was collectively responsible for refocusing the attention of researchers away from behaviorist perspectives on play to more of a cognitive orientation through the major cognitive psychological movement of the 1960s.

Play and Adult Learning

Gitlin-Weiner (1998) summarizes the work of several researchers by stating that some of the common features that adults associate with play suggest that it is pleasurable, the antithesis of work, free of extrinsic goals, and an absorbing process involving the temporary loss of awareness of one's surroundings. Gitlin-Weiner also describes adult play as non-literal, spontaneous, an

7

opportunity to bestow novel meanings onto objects, and an overt expression of wishes and hopes.

Gordon (1961) states that play in adults is not a lighthearted waste of time, but is a constructive effort constituting a serious, form-making endeavor.

Cognitive Influences on Play

The shift to a cognitivist mindset, which promotes active mental processing and systematic changes in knowledge states, also does not allow great flexibility for the affective impact of play, which is often emotionally charged and fluid. Cognitive learning emphasizes highly structured, hierarchical instruction that is linear and well defined. Constructivist instruction, with its emphasis on student-centered learning, the active construction of knowledge, subjective meaning, and learning situated in authentic, real-world environments, provides a more open and acceptable place for play in instruction.

Play and Creativity

A number of correlational studies indicate that a relationship exists between play and creativity. Alternately, creativity is defined as ideational fluency, flexibility, and originality (Wallach & Kogan, 1965), and associative fluency (Dansky & Silverman, 1973). Play and creativity have much in common. Play often involves symbolic transformations in which objects and actions are used in new and unusual ways, which is similar to the novel, imaginative combination of ideas which usually result from creative thinking (Christie & Johnsen, 1983). Gordon, in his theory of Synectics (1961), believed play to be the “activity of floating and considering associations apparently irrelevant to the problem at hand” (p. 118). In this sense, Gordon emphasized, play involves constructive illusion, conscious self-deceit, daydreams, and general associations marked by no immediate benefit.

8

Play and Problem-Solving

A number of studies exist on the role of play in the problem-solving behavior of primates

(Christie & Johnsen, 1983). Sylva, Bruner, & Genova (1976) conducted one of the first studies on play and problem solving in children. Subjects were exposed to three treatment conditions:

(a) observation of the complete solution, (b) free play with solution instruments, and (c) no treatment. The play group did as well at problem-solving than did the group exposed to the complete solution and much better than the control group, as well as exhibiting more persistence and goal-directed behavior. Smith and Dutton (1979) modified the 1976 study, varying the levels of difficulty in the problem-solving tasks and providing both observation and training to one group, freeplay in another, and no treatment in a third. Their results showed that the children in the play group solved problems better than either the observation and training group and the control group.

Play and Motivation and Exploration

Other researchers have examined the motivational characteristics of play rather than its cognitive or structural aspects (Christie & Johnsen, 1983). Wolfe, Cummins, & Myers (1998) state that explorative play must be characterized by "as-if" thinking, be internally motivating, and personally meaningful. The research of Berlyne (1960) presents a model of motivation based on arousal control, suggesting that organisms function comfortably with moderate stimulus information. When the stimulus changes to that of novelty or incongruity, the organism responds with a motivational state of curiosity (Christie & Johnsen, 1983). Exploration or investigation occurs to allow the organism to gather enough information to assimilate and comprehend the situation, reducing the arousal level. When environmental stimuli are insufficient to maintain a

9

high level of arousal, the organism seeks a diversion through exploration which, Christie &

Johnsen (1983) state, might be called play.

Bruner's contention that play minimizes the consequences of actions, allowing individuals to "try out" behaviors without risk, and Erikson's belief that play is practice for future roles in adulthood (Lentz, 1982) lends credibility to play as an explorative device. The idea of exploratory play as a means to assimilate novel experience also meets Piaget's concepts of assimilation and accommodation (Piaget, 1962). Singer (1995) posits that the playful attempt of children to explore and manipulate experiences is related to Piaget's notion of assimilation of information to established schemas. In this process of assimilation, Singer states, the child experiences joy through the repetitive linking of earlier material with novelty. In addition, Piaget's (1962) idea of equilibrium and disequilibrium is similar to Berlyne's (1960) idea of stimulus-based arousal; until the information is assimilated into the existing knowledge base, disequilibrium occurs.

Both concepts resonate with Vygotsky's zone of proximal development, in which the development of individuals is accelerated through peer interaction. Wolfe, Cummins, & Myers (1998) state that exploratory play creates cognitive scaffolding within the player, and possibly allows growth beyond current competencies in the absence of peer interactions. Merrill (1997) describes play as a way of encouraging exploration in procedural learning. He recommends that designers provide an opportunity for students to “play with” a procedure, to allow the student to explore “what happens if” by trying out a variety of actions and observing the consequences. He supports the conclusion of Wolfe, Cummins, & Myers (1998) that exploratory play can be a form of cognitive scaffolding if help is provided in the early stages of practice, with the gradual withdrawal of the help until the student is able to perform the entire task without further guidance.

10

A Cognitive Model of Play and Learning

The relationship of play to cognitive development and learning is embedded in different domains of thought and research. Early in the study of thought and reason, Aristotle considered imagination to be the way that images are presented to the mind, stating that “the soul never thinks without an image” (De Anima, 431a, 15-20). Much later, Paivio created his “Dual

Coding Theory” (available: www.gwu.edu/~tip/paivio.html

) in which he assumed that there are two cognitive subsystems, one specialized for the representation and processing of nonverbal events and the other for dealing with language. Paivio believed that learning is enhanced when both cognitive subsystems are engaged; that is, when the learner processes both verbal and nonverbal items. Craik and Lockhart (1972) studied memory and concluded that knowledge that gets encoded into memory depends on the depth or level of processing of the presented information as it is encoded into memory. The depth of processing, in turn, depends on the continuum of sensory to semantic processing. Jonassen (1988) studied microcomputer courseware and composed a set of assumptions about how learning occurs, including:

Learners need to attend to stimuli;

Learners need to access existing knowledge to which to relate new knowledge;

Learners need to realign the structure of existing knowledge to accommodate the new information;

Learners need to encode the restructured knowledge base into memory; and

Meaning is individualized, constructed by the learner, using existing knowledge as the foundation for interpreting information and building new knowledge.

Jonassen echoed Craik and Lockhart’s emphasis on increasing the depth of processing through the use of appropriate instructional strategies in courseware to promote the above methods for

11

learning. Among other methods for increasing processing depth include mental imagery, reflecting Paivio’s beliefs, and Wittrock’s generative hypothesis (1978), which holds that meaning is generated by activating and altering existing knowledge structures in order to intepret what is presented. Generative learning is dependent on a complex set of elaborations and transformations unique to each learner (Jonassen, 1988).

Play and Instructional Design

Seymour Papert (1996), writing about learning, notes that while there are plenty of words in our language for the art of teaching, there is no such word for the art of learning. What about methods of learning, he says? What kinds of courses are offered for those who want to become skilled learners? Papert goes on to say:

The same imbalance can be found in words for the theories behind these two arts. “Theory of Instruction” and “Instructional Design” are among many ways of designating an academic area of study and research in support of the art of teaching. There are no similar designations for academic areas in support of the art of learning.

Papert, 1996, p. 9

Instructional design is in search of a systematic means to design good, sound instruction.

Gagne, Briggs, & Wager (1992) state that instruction is a human undertaking whose purpose is to help people learn. As seminal thinkers in instructional design, they believe that instruction must be planned if it is to be effective. The purpose of designed instruction, they state, is to activate and support the learning of the individual student. How then does systematic, planned instructional design mesh with the sporadic, spontaneous, flexible nature of play?

Gagne, Briggs, and Wager (1992) list five abiding assumptions for the design of instruction. These are:

12

1.

Instructional design must be aimed at aiding the learning of the individual;

2.

Instructional design has phases that are both immediate and long-term;

3.

Systematically designed instruction can greatly affect individual human development;

4.

Instructional design should be conducted by means of a systems approach; and

5.

Designed instruction must be based on knowledge of how human beings learn.

Assumptions 1-4 indicate that instruction should be systematic and aimed directly at the individual. These assumptions indicate a rigidity of sorts within the field of design toward any type of instructional activity that is fluid and/or constructed by the learner. Assumption number five, however, provides a glimmer of access into taking the knowledge of how humans learn and folding it into the way instruction is designed. If play is one way in which humans can learn, then it stands to reason that instructional designers should study play to understand more about how it can be used as a systematic instructional strategy to aid the learning of the individual.

An aim of this study was to isolate the conditions or characteristics of play so that instructional designers can use these components to design instructional strategies that aid student learning. Currently, designers do not possess a knowledge base regarding the inclusion of play in instructional strategies. Merrill (2000, p.2) describes this problem in more generic terms:

At the heart of my argument is that students must engage in those activities (conditions of learning) that are required for them to acquire a particular kind of knowledge or skill. These activities can be directed by an instructional system (live or technology-based) or they can be engaged in by the student on their own. However (a) many instructors do not know these fundamental instructional strategies, consequently much of what passes for instruction is inadequate and does not adequately implement these fundamental learning activities; and (b) most students are unaware of these fundamental instructional (learning) strategies and hence

13

left to their own are unlikely to engage in learning activities most appropriate for acquiring a particular kind of knowledge or skill.

The analysis and identification of the characteristics and conditions of play in learning will be a solid contribution to the field of instructional design, in that it will become a new rubric for the design of play within instruction. A long-term goal is to identify the "conditions of play” to prescribe them for use by instructional designers. If so, it will mark a new era in the study and application of understanding regarding play and the ability to train designers to “design play.”

Methods, Techniques and Modes of Inquiry

Methods of Data Collection

This study used a mixed method design to assess the effectiveness of using play as an instructional strategy on a procedural learning outcome as well as measuring the impact play on participant enjoyment. The mixed-method design also was designed to probe participants to learn the indicators of play.

Data collection methods in this study included participant observation, interviewing, and quantitative analysis of an instructional intervention of a multimedia unit of instructional play into an existing course using treatment and comparison groups. Multiple data collection methods were used to target a new understanding of play and its relationship to learning and instruction. Quantitative methods were used to provide a numerical description of the value of one instructional method over another.

Settings

The primary setting was the Cryptologic Technician Administrative (CTA) "A" School onboard the Naval Technical Training Center, Corry Station, Pensacola, Florida. Within this

14

setting, students were observed, interviewed, and tested to document their perceptions of play and learning from the phenomenological, experiential, and learning perspectives.

Participants

Participants in the primary setting onboard NTTC Corry Station were demographically similar in age and prior knowledge. Participants were both male and female students, ranging in age from 18-22 years old. Other participants onboard NTTC Corry Station included Navy instructors who are responsible for teaching the Navy students in the CT “A” school. Participants in the secondary setting at the Raytheon office in Pensacola were professional instructional designers and multimedia developers, ranging in age from mid-twenties to mid-sixties. One graphic artist also participated.

Data collection was based on three major methods: Interviewing, intervention of a multimedia treatment, and observation.

Interviews

In the primary study setting onboard NTTC Corry Station, participants were interviewed to determine the following:

Past experiences with play;

Perception of the relationship between play and learning;

Indicators of play; when and why they recognize and self-report activities as playful;

How play in learning impacts their motivation for the content and learning outcomes;

How play in learning engages their emotions and interest;

If play can be experienced in isolation or if it only occurs in social groups;

How, during play, they interact with each other and with the source of play to create meaning; and

15

How play can be embedded within instruction without distracting from learning goals.

Raytheon instructional designers and multimedia developers and Navy instructors were interviewed to determine the following:

Past experiences with play;

Perception of the relationship between play and learning;

Indicators of play; when and why they recognize and self-report activities as playful;

How play in learning impacts their motivation for the content and learning outcomes;

How play in learning engages their emotions and interest;

If play can be experienced in isolation or if it only occurs in social groups;

How play can be designed into instruction;

The events or conditions of play within instruction;

How play can be matched with learning outcomes;

The relationship between play and cognitive and/or affective outcomes; and

The nature of play as a behaviorist, constructivist, or cognitive learning phenomenon.

Multimedia Treatment Intervention

The play intervention consisted of a course of interactive multimedia instruction titled

“Standard Naval Letter.” The purpose of this course is to teach Navy, Marine, Army, and Air

Force students the procedural steps to write a Standard Naval Letter according to guidelines published in the Naval Correspondence Manual. Two versions of the course were created.

Version A contained the existing course along with an additional module of instructional play, and version B contained the existing course along with an additional module of practice questions without play characteristics. The hypothesis examined was that the treatment group receiving the play module would score significantly higher on content and skill posttests than the

16

comparison groups, and that the treatment group receiving the play module would express higher enjoyment ratings than those receiving the module without play characteristics.

Version A, which contained the play module given to the treatment group, was accessible from the main menu or from a linear path through the courseware, and was sequenced so that it is at the end of the instruction, but before the lesson test. Students were required to complete the module. Although required participation violates a commonly defined characteristic of play – that of voluntary or spontaneous action, it was necessary for testing purposes. The module was based on a metaphoric spoof of the David Letterman show and contained a menu with three branches: the Top Ten Ways to Mess Up a Standard Naval Letter, Stupid Letter Tricks, and

Celebrity Visit. In the Top Ten Ways to Mess Up a Standard Naval Letter, the most common letter-writing and formatting mistakes (as identified by the CTA instructors) were portrayed textually and graphically as non-examples, with additional instruction showing students the correct way to format the letter. Stupid Letter Tricks contained a silly series of five ways to use

Standard Naval Letters in non-traditional ways. The Celebrity Visit contained an audio interview between David Letter-Man and the Navy Chief of the CTA School regarding common mistakes made when writing Standard Naval Letters.

The inclusion of play was based upon Levy’s characteristics of playful behavior. Novelty, incongruity, and surprisingness, as described by Levy (1978), were embedded to stimulate the feeling of playfulness in the participants.

Coding Procedures

Interview data were recorded and later transcribed into a Microsoft Word rich text file

(.rtf) for incorporation into QSR NVivo. An analysis of major themes arising from the interview data produced 23 codes, or categories of data, that could be used to identify indicators and

17

perceptions of play. The interview data were analyzed for common patterns or descriptions used frequently by the participants to identify the indicators or elements as well as the ways play can be used in learning. Using the automated coding feature, segments of interview data were then selected and assigned a code (or codes). At times, multiple codes were assigned to a single passage of interview data. For example, one instructor defined play as “enjoyable social activity”; this statement was coded in three ways: as enjoyment, activity, and social-dependent.

Quantitative Data

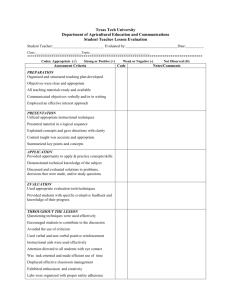

The quantitative analysis utilized a randomized posttest-only control group design with random assignment into both the treatment and control groups. The primary dependent or response variable to be measured consisted of the scores on three different summative measurements. These three dependent variables were as follows:

a content knowledge test score, taken from the test embedded into the multimedia course,

a skill performance measure, taken from the job sheets completed by the students in the follow-on lab.

a summated rating scale measuring enjoyment

The explanatory or independent variable was the additional play module attached to the existing

Standard Naval Letter multimedia course.

Instrumentation

The content knowledge test was an end-of-course test embedded in the Standard Naval

Letter course. Students completed it after finishing all lesson modules, including the Letter-Man play module or the additional practice module, depending on the version they were given. This test contained twelve questions that were comprehensive over the entire course. The question format breakdown was as follows:

18

Five true-false questions

Six multiple choice questions

One interactive question (student must click on the incorrect letter component)

The courseware automatically calculated and reported a percentage score based on the number correct.

The skill performance measure was referred to as a “job sheet” by the Navy instructors, and provided a scenario in which a problem can only be solved by writing a Standard Naval

Letter. The students were given the basic information, including whom is writing the letter, who it should be sent to, and other personnel involved. The student was required to read and comprehend the scenario and then construct a Standard Naval Letter with proper formatting. The Navy instructors scored the letter and calculated a numerical score based on number of letter components that were properly formatted. Ten points were subtracted for every error in formatting or spelling.

The enjoyment scale was based on questions designed by Mihaly Csikszentmihayli (1990) to measure flow. It is a summated rating scale that consists of 7 questions. This instrument was analyzed to determine if enjoyment ratings were higher for either group. The validity of the questions was established in previous research by Mihaly Csikszentmihayli, who used them to measure “flow,” which is a form of enjoyment in which a person becomes engaged in a task so much that time passes without notice (Csikszentmihayli, 1979). The questions on the scale were summed and averaged to report group results for each participant. Group means were obtained for each question and for the total scale.

19

Experimental Design and Data Analysis

The posttest only control group design was used to determine if the independent variable

(the multimedia play treatment) produced significant differences in the treatment group when compared to the comparison group. Random assignment into groups equated the groups on extraneous variables. A pretest was not used because of the possible sensitizing effect, in which students respond to the posttest due to learning from the pretest rather than the treatment, which can decrease the external validity of the experiment. In addition, the letter-writing content was novel to these students, thus greatly diminishing the value of a pretest.

A one-way analysis of variance was used to compare the mean scores of the treatment and comparison groups to see if the difference was statistically significant. In other words, this study sought to determine if the two groups were different after taking two different versions of the Standard Naval Letter course. An alpha level of 0.05 or lower was the selected level of significance necessary for the results to be considered significantly different.

Results of the Study

The first research question posed in this study described a need to identify the indicators of play from three different perspectives: What are the indicators of play?

1.

What are the indicators of play from a learner's perspective--how do they experience play?

2.

What are the indicators of play from an instructor’s perspective?

3.

What are the indicators of play from an instructional designer’s perspective--how do they describe the design of play?

The attempt to identify a common set of indicators was made because it was important to the study of play and any future application of play as an instructional strategy. Common indicators could form the basis of a play taxonomy, or a categorization of the kinds and levels of

20

play and how play can be designed to meet certain instructional outcomes in a controlled instructional setting.

Prior to these interviews, a review of the literature was conducted. Sixteen researchbased indicators of play were identified through the literature review. Sixteen additional indicators were identified through interviews that were not found in the literature. Cross-over did occur between some indicators found both in the literature in and interview data. Table 1.0 lists the combined indicators and notes whether they were obtained from the literature review or the interview data (gleaned from student, instructor, and designer interviews.) Indicators can best be understood as descriptors by which the presence of play was implied.

Table 1.0 Indicators of Play Derived from the Literature Review and Interview Data

Indicators derived from Literature

Review

Self-generated

Intrinsic Motivation

Pleasurable

Sense of Humor/Fun

Joy, Enjoyment

Exuberance

Empowerment

* Negotiation

* Creative Risk-Taking

* Non-literal what-ifs

* Exploratory

Spontaneous

Absorption

Non-work

Constructive Illusion-Individual

Constructive Illusion-Group

* Indicators from the literature review that were not confirmed by interview data

Indicators derived from Interviews

Stimulating

Focused Attention

Silliness

Relaxed

Lack of boredom

Lack of anger/stress

Competitive

Helps knowledge acquisition

Timelessness

Location-dependent

Socially-dependent

Performance

Balance

Time on task/focus

Play instruments

Expense

Fidelity/simulation

21

Interestingly, six coded indicators occurred frequently across all interview groups and the literature review. These indicators are noted below with the frequency of occurrence:

Sense of humor/fun (N=27)

Helps knowledge acquisition (N=27)

Socially-dependent (N=27)

Timelessness/flow (N=26)

Joy/enjoyment (N=17)

Lack of anger/stress (N=16)

Quantitative Results

As described in Chapter 2, previous research suggested that play can be an effective tool for increasing procedural learning as well as learner enjoyment (Frost, 1992; Christie & Johnsen,

1983; Lieberman, 1977). This study used a mixed-method design to evaluate whether play, as an instructional strategy, was more effective in helping participants in a treatment group acquire and retain procedural information and increase enjoyment than those in a comparison group. Research question two asked whether play impacts enjoyment for learning. Two subsequent hypotheses were proposed. Hypothesis one stated that play, used as an instructional strategy, would aid participants in a treatment group to score higher on post-instruction tests than participants in a comparison group who received instruction that did not include play. Hypothesis two stated that the participants in the treatment group would report greater enjoyment of the instruction than those in the comparison group.

Hypothesis One

The study of the effects of play on student performance was undertaken to investigate hypothesis one, that play would aid participants in a treatment group to score higher on post-

22

instruction tests than participants in a comparison group who received instruction that did not include play. Results of the effects of play on post-CBT measurements did not support this hypothesis.

As an instructional strategy, play only showed a significant effect on the performance of the participants on one of the 3 dependent variables (i.e. the CBT Test). In all cases, the mean score of the comparison group was higher than the mean score of the treatment group, resulting in an effect in an opposite direction from what was expected. This was a surprising finding.

As already mentioned, hypothesis one was not supported by the results of the study. Oneway analysis of variance was used to determine if the observed difference between the two group means was statistically significant. The two different dependent variables used were the CBT

Test and the Letter-Writing Test. Table 2.0 contains these results.

Table 2.0 Results of the CBT and Letter-Writing Tests

CBT Test

Letter-Writing Test

Play Mean

72.9

-42.59

Non-Play Mean

81.3

-35.71 p-value

.008

.569

Examining the CBT Test, the Non-Play Comparison Group scored higher than the Play

Treatment Group (Non-Play Comparison Group, m=81.2571; Play Treatment Group, m=72.9355). The p-value was below the selected alpha level of .05 (p=.008), so the differences between the two groups was statistically significant. The mean scores are notable because the comparison group obtained a higher mean score than the treatment group.

Examining the Letter-Writing Test, the Non-Play Comparison group scored higher than the

Play Treatment Group (Non-Play Comparison Group, m=-35.7143; Play Treatment Group, m=-

42.5862). The p-value was higher than .05 (p=.569), so the differences were not found to be

23

statistically significant. Despite the lack of statistical significance, it is again notable that the comparison group obtained a higher mean score than the treatment group.

Hypothesis Two

The second hypothesis, which proposed that the treatment group would score significantly higher on enjoyment of the instructional unit than the comparison group, was also not supported by the results of the study. Statistical tests did not yield statistical significance at the alpha =.05 level, but further tests with more participants are recommended to determine if the play intervention did not have any significant effect on enjoyment scores.

The internal reliability of the questions on the Enjoyment Scale was established by using

Crobach’s alpha coefficient. The summated rating scale had an alpha coefficient of .7983, which indicates a fairly high degree of reliability for the scale. Students responded to the enjoyment items with a Likert scale rating response.

All seven Enjoyment Scale questions were summed and averaged, and an independent samples t-test was used to compare these averages. Again, the Non-Play Comparison Group scored higher than the Play Treatment group (Non-Play Comparison Group, m=81.9118, Play

Treatment Group, m=77.0323). The p-value was greater than .05 (p=.106), so the difference was not found to be significant. The questions in the scale were as follows:

1.

I found myself challenged to optimal levels.

2.

My attention was completely absorbed in this activity.

3.

This module had clear goals.

4.

This module had clear and consistent feedback and helped me to know if I was meeting the right goals.

5.

During the module, I felt free from worry or other distractions.

24

6.

I felt completely in control of my learning.

7.

Time passed without my notice.

In addition to the averages of the question answers, an independent samples T-test was used for each of the seven Enjoyment Scale questions to determine if significant differences existed between the two groups in the study on the individual questions. Table 3.0 contains the mean scores and p-values for each item by group, along with an identification of the item content.

Table 3.0 Group Means of Enjoyment Scale Items

Enjoyment

Scale Item

Treatment

Group

Mean

3.4194 Item 1 challenge

Item 2 attention

Item 3 clear goals

Item 4 clear feedback

Item 5 free from worry

Item 6 control

Item 7 lack of time awareness

3.7097

4.2258

4.0645

3.7742

3.9355

3.8387

Comparison

Group Mean

3.1471

3.8235

4.5588

4.3824

4.2647

4.5882

4.1471

Composite

Mean Scores

3.8534 4.1303

Mean Difference (Treatment minus Comparison)

.2723

-.1138

-.3333

-.3179

-.4905

-.6527

-.3084

-.3555 p-value

.346

.893

.555

.644

.471

.518

.637

25

Contribution to Instructional Design

The study of the effects of play on student performance was undertaken to investigate hypothesis one, that play would aid participants in a treatment group to score higher on postinstruction tests than participants in a comparison group who received instruction that did not include play. In addition, the study was undertaken to address hypothesis two, that the participants in the treatment group would report greater enjoyment of the instruction those in the comparison group. As stated earlier, results of the effects of play on post-CBT measurements did not support either hypothesis. However, one enjoyment scale item did reflect a higher mean score for the treatment group than the comparison group – that of challenge.

The quantitative findings did not at all support the initial hypothesis, given that the comparison group – the one not receiving instruction with play – performed better on every measure than the treatment group. Based on subsequent findings from the interview data, the conclusion is that the initial design of the instructional strategies using play in the treatment group module was flawed and did not adequately capture play into its instructional sequences. The play module was designed as a metaphoric spoof of the David Letterman show. Levy’s (1978) characteristics of play were used as a basis for design, and included novelty, surprisingness, and incongruity. These characteristics were represented by the module’s reliance on surprising graphics and audio, and by the complete incongruity between the lesson’s very dry presentation of Standard Naval Letter procedural formatting rules and the sudden change to the fun and entertaining David Letter-Man module. On paper, my design followed the characteristics of play as documented in the literature.

Later analysis of interview data revealed that the key indicators of play, at least as described by students, instructors, and instructional design practitioners, are not at all novelty,

26

incongruity, and surprisingness, but instead are focused attention, a sense of timelessness, balance, social dependence, joy/enjoyment, lack of anger and stress, and a sense of humor and fun. The description of the module by the students as “fun” and “entertainment” is the lone descriptor matching later interview data.

It appears that the design of the instructional strategies used in the Letterman module was fatally flawed in relation to the attempt to stimulate play or playfulness among the participants.

Later interview data revealed specific indicators, elements, ways to use play, and expected results of play that could have been used to design instruction that better stimulated the occurrence of play and created an instructional environment in which the subsequent effects of play could be measured. If the design of the module had come after the qualitative portion of the study, the design would have been based on more reliable data and the subsequent measurements might have resulted in different results. In fact, the indicators revealed by this study can easily be incorporated into the context analysis and needs assessment phases of design.

Table 4.0 W-I-R-E Indicators of Play

Way to Use Play

(W)

Indicator of

Play

(I)

Result of Using

Play

(R)

Element of Play

(E)

Edu-tainment

Constructive-

Illusion, Individual

Constructive-

Illusion, Group

Play Instruments

Self-Generated

Intrinsic Motivation

Stimulating

Focused Attention

Empowerment

Pleasurable Helps Knowledge

Acquisition

Fidelity/Simulation Sense of Humor

Imitation

Timelessness /

/ Fun Flow

Joy/Enjoyment Performance

Exuberance Time on task /

Relaxed

Lack of Boredom

Lack of anger/stress

Location-Dependent

Socially-Dependent

Balance

Silliness

Entertainment

Competitive focus

Expense

27

Non-literal what ifs

Spontaneous

Non-work /

Goal-free

Upon further analysis, these indicators identified by the study can be partitioned further into concepts more applicable for the creation of an instructional strategy involving play. The indicators themselves naturally fall into categories more usable for strategy-building, such as internal indicators, environmental elements, ways to use play, and the results of using play. For example, an internal indicator of play is intrinsic motivation; rather than being an instructional outcome or effect, evidence that players are intrinsically motivated is an identifier that play is occurring. Also, the concept of play as being dependent upon location or social engagement by others may also indicate play, but is more appropriately described as an environmental element necessary for play to occur. Additionally, constructive illusion may indicate the presence of play, but is more specifically defined as a way to use play in a daydreaming, imaginative sense.

Finally, the concept of play as a means to promote knowledge acquisition says more about knowledge acquisition as a potential result of using play rather than a leading indicator of the occurrence of play. Thus, while the indicators do indeed indicate the presence of play, each can be further defined into more useful concepts for application in instructional settings.

These categorizations can be summarized into an acronym titled W-I-R-E: W = ways to use play, I = indicator of play, R = results of using play, E = elements necessary for play to occur. For example, the W-I-R-E categories provide a concise shell in which the indicators (“I”) of play can be identified, the environmental elements (“E”) necessary for the stimulation of play can be embedded, and the prescriptions or ways to use play (“W”) can be specified. Additionally, this beginning model can also attempt to predict the possible results ("R" ) of using play.

28

After more specific testing under multiple learning outcomes and instructional contexts to prove its effectiveness, the W-I-

R-E model can be used in a more prescriptive manner by instructional designers. Table 4.0

Figure 1 T The W-I-R-E Model of Play contains the list of W-I-R-E indicators.

For example, as a metaphor, this model can be used by instructional designers as a way to

“WIRE” their instruction with play, embedding elements into the environment that will stimulate the indicators of play, while at the same time providing designers with specific tactics (ways) to deliver instruction through play. In this way, the components of play are interwoven throughout every aspect of instruction. Then, expected results can be predicted through this prescriptive approach.

In conclusion, the use of play within instruction is a viable practice for instructional designers. Much research needs to be done regarding play as an overlooked component of instructional design and learning. Further study on the impact of play on learning is recommended, especially in the relationships of play and instructional strategies, conditions of learning, and interactive multimedia instruction. Additionally, research exploring environments in which play occurs, as related to instruction, would be a welcome contribution to the field of instructional design.

29

References

Agar, M.H. (1980). The professional stranger. An informal introduction to ethnography. New

York: Academic Press.

Barell, J. (1980). Playgrounds of our minds. New York, NY: Teacher's College Press.

Beach, F.A. (1945). Current concepts of play in animals. American Naturalist, 79, 523-541.

Berlyne, D.E. ( 1968). Laughter, humor, and play. In G. Lindzey and E. Aronson (Eds.)

Handbook of social psychology. New York: Addison-Wesley.

Bodrova, El, & Leong, D.J. (1998). Adult influences on play. In D.P. Fromberg & D. Bergen

(Eds.), Play from Birth to Twelve and Beyond: Context, Perspectives, and Meanings. New

York: Garland Publishing.

Bogdan, R.C., and Biklen, S.K. (1998). Qualitative research in education: an introduction to theory and methods. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Bowman, J. R. (1978). The organization of spontaneous adult play. In M. A. Salter (Ed.), Play:

Anthropological Perspectives (pp. 239-250). West Point, NY: Leisure Press.

Briggs, L.J, & Wager, W.R. (1981). Handbook of procedures for the design of instruction.

Educational Technology Publications, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Bruce, T. (1993) The role of play in children's lives. Childhood Education, Summer, pp. 237-

238.

Bruner, J. (1966). Toward a theory of instruction. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press.

Burns, S.M., and Brainerd, C.J. (1979). Effects of constructive and dramatic play on perspective taking in very young children. Developmental Psychology, 15, 512-521.

Cheska, A.T. (1978). The study of play from five anthropological perspectives. In M. A. Salter

(Ed.), Play: Anthropological Perspectives (pp. 17-35). West Point, NY: Leisure Press.

Cheska, A.T. (Ed.). (1979). Play as context. West Point, NY: Leisure Press.

Christie, J.F., and Wardle, F. (1992) How much time is needed for play? Young Children,

March, pp. 28-31.

Christie, J.F., and Johnsen, E.P. (1983). The role of play in social intellectual development

Review of Educational Research, 53, 93-115

Creswell, J.W. (1994). Research design: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Csikszentmihayli, M. (1979). The concept of flow. In B. Sutton-Smith (Ed.), Play and Lear- ning (pp. 257-274). New York, NY: Gardner Press.

Csikszentmihayli, M. (1979). Overview: Play or flow? In B. Sutton-Smith (Ed.), Play and

Learning (pp. 275-294). New York, NY: Gardner Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: the psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper

& Row.

Craik, F.I.M., Lockhart, R.S. (1972). Levels of processing: a framework for memory research.

Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11, 671-684.

Dansky, J.L. (1980). Make-believe: a mediator of the relationship between play and associative fluency. Child Development, 51, 576-579

Denzin, N.K. (1989). The research act: a theoretical introduction to sociological methods.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Denzin, N.K., and Lincoln, Y.S. (Eds.). (1998). The landscape of qualitative research. Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Dinwiddie, S.A. (1993) Playing in the gutters: enhancing children's cognitive and social play.

30

Young Children, September, pp. 70-73.

Duffy, T.M., & Cunningham, D.J. (1996). Implications for the design and delivery of instruction. In Jonassen, D.H. (Eds.) Handbook of research for educational communications and technology. p. 170-198.

Ellis, M.J. (1973). Why people play. Englewood Cliffs: NJ. Prentice-Hall.

Fein, G.G., & Wiltz, N.W. (1998). Play as children see it. In D.P. Fromberg & D. Bergen

(Eds.), Play from birth to twelve and beyond: context, perspectives, and meanings. New

York: Garland Publishing.

Flake-Hobson, C., Skeen, P., and Robinson, B.E. (1982). Learning to read through play.

Dimensions, July., pp. 103-105.

Fromberg, D.P., & Bergen, D. (Eds.). (1998). Play from birth to twelve and beyond: context, perspectives, and meanings. NY: Garland Publishing.

Gagne, R.M, Briggs, L.J., & Wager, W.W. (1992). Principles of instructional design. Orlando:

Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Garvey, C. (1977). Play. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Golumb, C., & Cornelius, C. (1977). Symbolic play and its cognitive significance.

Developmental Psychology, 13, 246-252.

Gooler, D., & Stegman, C. (1994). A scenario of education in cyber city. Paper Presented to the

Japan-United States Teacher Education Consortium (JUSTEC) meeting, Hiroshima, Japan.

Gordon, W.J.J. (1961). Synectics: the development of creative capacity. New York: Harper.

Gredler, M. (1996). Educational games and simulations: a technology in search of a paradigm.

In Jonassen, D.H. (Ed.) Handbook of research for educational communications and technology, p. 521-540.

Guilmette, A. M., and Duthie, J.H. (1979). Play: a multiparadoxical phenomenon. In A. T.

Cheska (Ed.), Play as Context (pp. 36-41). West Point, NY: Leisure Press.

Guilmette, A.M., & Duthie, J.H. (1982). Playing to grow and growing to play. In Loy, J.W.

(Ed.), The Paradoxes of Play. New York: Leisure Press.

Gulick, L. H. (1972). Philosophy of play. New York: C. Scribner’s Son’s.

Harris, J. C. (1979). Beyond Huizinga: relationships between play and culture. In A. T. Cheska

(Ed.), Play as Context (pp. 26-35). West Point, NY: Leisure Press.

Herron, R.E., & Sutton-Smith, B. (1971). Child’s play. New York: Wiley.

Honebein, P.C. (1996). Seven goals for the design of constructivist learning environments. In

Wilson, B.G. (Ed.). Constructivist learning environments: case studies in instructional design. p. 11-18.

Huizinga, J. (1955) Homo-ludens: a study of the play element in culture. Boston: Beacon

Press.

Isenberg, J. (1998). Play among education professionals. In D.P. Fromberg & D. Bergen (Eds.),

Play from Birth to Twelve and Beyond: Context, Perspectives, and Meanings. New York:

Garland Publishing.

Isenberg, J, and Quisenberry, N.L. (1988) Play: a necessity for all children.

Childhood Education February, pp 138-145.

Johnson, J.E., & Ershler, J. (1982). Sex differences in preschool play as a function of classroom program. In Loy, J.W. (Ed.), The Paradoxes of Play. New York: Leisure Press.

Johnson, R.B. (1997). Examining the validity structure of qualitative research. Education, 118

(2), 282-292.

Johnson, R.B. & Christensen, L.B. (2000). Educational research: Quantitative and qualitative

31

approaches. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Jonassen, D. H. (1988). Instructional designs for microcomputer courseware. Hillsdale, NJ:

Erlbaum.

Jonassen, D.H. (Ed.). (1996). Handbook of research for educational communications and technology. NY: Macmillan.

Jones, E. (1990). Playing is my job. Thrust for Educational Leadership, pp. 10-13.

Jones, Marshall G. (1997). Learning to play; playing to learn: lessons learned from computer games. [WWW document] URL http://intro.base.org/docs/mjgames/.

Kafai, Y. (1995). Minds in play: computer game design as a context for children’s learning.

Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kafai, Y., & Resnick, M. (Eds.). (1996). Designing, thinking, and learning in a digital world.

New Jersey: Erlbaum

Kerr, J.H., and Apter, M.J. (eds) (1991). Adult play: a reversal theory approach. Berwyn, PA:

Swets & Zeitlinger.

LeCompte, M.D. & Preissle, J. (1993). Ethnography and qualitative design in educational research. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Lentz, K. (1982) Mastery through play. Dimensions, April, pp. 68-71.

Lepper, M.R. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and instruction: conflicting views on the role of motivational processes in computer-based education. Educational Psychologist, 20 (4), 217-

230.

Leshin, C.B., Pollock, J., Reigeluth, C.M. (1992). ID strategies and tactics. Englewood Cliffs,

NJ: Ed Tech Publications.

Levy, J. (1978). Play behavior. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Lieberman, J.N. (1977) Playfulness: in relationship to imagination and creativity. New York,

NY: Academic Press.

Linn, R.L, & Erickson, R. (1990). Quantitative methods, qualitative methods. Research in

Teaching and Learning, Volume 2. Macmillan Publishing, New York.

Loy, J.W. (Ed.). (1982). The paradoxes of play. NY: Leisure Press.

Manning, M.L, and Boals, B.M. In defense of play. Contemporary Education, 58 (4), Summer

1987, pp. 206-209.

Merriam, S.B. (1993) An update on adult learning theory. New Directions for Continuing

Education, (57), Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

Merrill, M.D. (1997). Instructional strategies that teach. CBT Solutions, November/December,

1-11.

Merrill, M.D. (1998). Knowledge analysis for effective instruction. CBT Solutions,

March/April, 1-11.

Merrill, M.D. (2000). Instructional strategies and learning styles: which takes precedence? In

Reiser, R., and Dempsey, J.V. (Eds.) (In Press). Trends and issues in instructional technology. NY: Prentice Hall.

Miller, S.N. (1973). The playful, the crazy, and the nature of pretense. American

Anthropological Association Meetings, New Orleans, LA.

Monighan-Nourot, P. , Scales, B., Van Hoorn, J and Almy, M.( 1987) Looking at children's play: a bridge between theory and practice. New York, NY: Teacher's College Press.

Morris, S.R. (1998). No learning by coercion: paidia and paideia in Platonic philosophy. In D.P.

Fromberg & D. Bergen (Eds.), Play from Birth to Twelve and Beyond: Context, Perspectives, and Meanings. New York: Garland Publishing.

32

Moyles, J (1994). Excellence of play. Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Neuman, S.B., Roskos, K.. (1990) Play, print, and purpose: enriching play environments for literacy development. The Reading Teacher, 44, (3), pp. 214-221.

Papert, S Kafai, Y. (1996). A word for learning. In Constructionism in Practice: Designing,

Thinking, and Learning in a Digital World, (eds) Yasmin Kafai, Mitchel Resnick. Mahwah,

NJ: Erlbaum.

Papert, S. (1993). The children's machine: rethinking school in the age of the computer. New

York: Basic Books.

Papert, S. and Harel, I. (1994). Self-regulation of learning and performance: issues and educational applications. In Papert & Harel (Eds.)., Constructionism: research reports and essays 1985-1990. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing.

Papert, S. & Harel, I. (Eds.). (1994). Constructionism: research reports and essays 1985-1990.

Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing.

Papert, S. (1996). A word for learning. In Kafai & Resnick (Eds.). Designing, thinking, and learning in a digital world. New Jersey: Erlbaum.

Patton, M.M., and Mercer, J. (1996) Hey, where's the toys? Play and literacy in first grade.

Childhood Education, Fall. pp. 10-16.

Patton, M.Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Newbury Park: Sage

Publications.

Paivio (1997). Dual coding theory [WWW document]. URL http://www.gwu.edu/~tip/paivio.html

Pellegrini, A., and Galda, L (1982). Effects of thematic-fantasy play training on the development of children's story comprehension. American Educational Research Journal, 19, (3).

Pellegrini, A.D. (Ed.). (1995). Future of play theory: a multidisciplinary inquiry into the contributions of Brian Sutton-Smith. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Perlmutter, J.C., and Burrell, L.(1995) Learning through "play" as well as "work" in the primary grades. Young Children, July pp. 14-21

Piaget, J. (1951). Play, dreams, and imitation in childhood. New York: Norton.

Post, D.L. (1978). Piaget’s theory of play: a review of the critical literature. In M. A. Salter

(Ed.), Play: Anthropological Perspectives (pp. 36-41). West Point, NY: Leisure Press.

Provenzo, E.F. (1998). Electronically mediated playscapes. In D.P. Fromberg & D. Bergen

(Eds.), Play from Birth to Twelve and Beyond: Context, Perspectives, and Meanings. New

York: Garland Publishing.

Reigeluth, C.M.. (1983). ID theories and models: an overview of their current status. Hillsdale,

NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Rieber, L.P., Smith, L & Noah, D. (1988). The value of serious play. Educational Technology,

Nov/Dec 98 pp 29-37.

Rieber, L. (1996). Seriously considering play: designing interactive learning environments based on the blending of microworlds, simulations, and games. Educational Technology Research and Development, 44, (2) pp. 43-58.

Reiser, R., & Dempsey, J.V. (Eds.). (2000). Trends and issues in instructional technology. NY:

Prentice Hall.

Rubin, K.H., Maioni, T.L., and Hornung, M. (1976). Freeplay behaviors in middle and lower class preschoolers: Parten and Piaget revisited. Child Development, 47, 414-419.

Rubin, K.H., Watson, K.S., and Jambor, T.W. (1978). Freeplay behavior in preschool and kindergarten children. Child Development, 49, 534-536

33

Rubin, K.H., Fein, G. and Vandenburg, B. (1983). Play. in Handbook of child psychology: socialization, personality, and social development, 4, pp. 693-774

Saracho, O.N. (1986). Play and young children's learning. Today's Kindergarten.

Sawyers, J.K., & Horm-Wingerd, D.M. (1993). Creative problem solving. . In Aronson, J.

(Eds.). Therapeutic Powers of Play, Northvale, NJ, pp. 81-105.

Schwandt, T.A. (1998). Constructivist, interpretivist approaches to human inquiry. In Denzin,

N.K., & Lincoln, Y.S. (Eds.). Landscape of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA, pp.

221-259.

Schwartzman, H.B. (1982). Play and metaphor. In Loy, J.W. (Ed.), The Paradoxes of Play.

New York: Leisure Press.

Seefeldt, C. (1985). Tomorrow's kindergarten: pleasure or pressure? Principal, May, pp10-15.

Singer, J.L.(1973) The child's world of make-believe: experimental studies of make-believe play.

New York, NY: Academic Press.

Stone, S.J. (1995/96). Integrating play into the curriculum. Childhood Education, Winter 95/96. pp. 104-107.

Stone, S.J.(1995) Wanted: advocates for play in the primary grades. Young Children, September, pp. 45-54.

Strother, D.B. editor (1992 Dec) Practical Applications of Research, Newsletter 5(2), pp. 1-4.

Phi Delta Kappan Center on Evaluation, Development, and Research. Bloomingon, Indiana.

Sutton-Smith, B. (1979). Play and learning. New York, NY: Gardner Press.

Tabachnick, B.G., & Fidell, L.S. (1996). Using multivariate statistics. New York, NY:

HarperCollins.

VanderVen, K. (1998). Play, proteus, and paradox: education for a chaotic and supersymmetric world. In D.P. Fromberg & D. Bergen (Eds.)., Play from birth to twelve and beyond: context, perspectives, and meanings. New York: Garland Publishing.

Van Patten, J., Chao, C. & Reigeluth, C.M . (1986). A review of strategies for sequencing and synthesizing instruction. Review of Educational Research, 56, 437-471.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1990). Imagination and creativity in childhood. Soviet Psychology, 28, p. 4-96.

Wilson, B.G. (Ed.). (1996). Constructivist learning environments: case studies in instructional design. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

Wolfe, C.R., Cummins, R.H., & Myers, C.A. (1998). Dabbling, discovery, and dragonflies: scientific inquiry and exploratory representational play. In D.P. Fromberg & D. Bergen

(Eds.), Play from birth to twelve and beyond: context, perspectives, and meanings. New

York: Garland Publishing.

34