Hatshepsut: History, Rise to Power, and Egyptian Society

advertisement

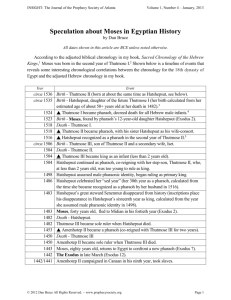

Hatshepsut Historical context: 1. ● ● ● ● ● ● ● Historical overview of early 18th Dynasty The interest in her has naturally focused on the fact that she was a woman in a man’s world, a woman who broke with tradition by establishing herself as a pharaoh. She also came to power at a time when Egypt was on the threshold of perhaps its greatest achievements in both internal and foreign affairs. The kingship were bound to the sate cult of Amun-Re In foreign affairs, Hatshepsut inherited the control of Nubia and the exploitation of its rich resources. In particular, its gold played an important role in Egypt’s economic development. Thutmose I was another important influence on her reign. She was mindful of the legacy she inherited from her predecessors, but she was also an innovator who set her own stamp on New Kingdom Egypt, especially in developing ideology of kingship and the theology of the state cult of Amun-Re Another source of inspiration came from her female forebears – Tetisheri, Ahhotep and Ahmose-Nefertari. These women had played an important role in the foundation and development of the early New Kingdom, often acting as regents in the troubled times of war. Women in Egyptian society derived their social status from the men to whom they belonged. Roles of royal women: ● ● ● Queen consort – any of the wives of the reigning king Regent – great royal wife and widow of a king, who managed the affairs of state for a new, young king until he was old enough to rule. Co-regent – ruled as a king in partnership with another pharaoh. 2. Overview of social, political, economic structures of early New Kingdom Social: ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● rigidly structured social hierarchy classes were well defined and social mobility was fairly limited but possible top of social hierarchy was the pharaoh then were the nobles and high government officials such as the vizier and army commanders the lower class included labourers, herders, fisherman and foot soldiers Nobility – royal family, viziers, high priests, king’s harem, harem officials Working classes – skilled – artists, scribes, craftsmen, sculptors, carpenters, jewellers Unskilled – farmers, labourers, fisherman, herders, slaves Political: ● main goal of the king was to provide security for the people by ensuring good relations with the gods and the maintenance of general prosperity and stability (ma'at) ● ● ● ● Royal Household – Chancellor, Chief Steward, Chamberlain State administration – vizier, overseer of the treasury, overseer of the granary, overseer of the king’s building works Imperial administration – viceroy of Nubia, Vassal kings, King’s deputies Exact rules for Egyptian succession are not known Military: ● ● involved in the consolidation of the empire - this is included by the exploits of Ahmose, Thutmose I and Thutmose III Nobility – commander in chief, chief deputies of the north and south, generals, scribe of infantry Economic: ● ● Agriculture was the main sector the expansion and consolidation of the empire also helped added to state revenues in the way of booty and imperial trade 3. Relationships of the king with Amun ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● The cult of Amun was centred at the state capital of Thebes, with its main temple in nearby Karnak All major policy decisions of state were justified and accredited to Amun Claimed divine birth and to be offspring of Amun-Re The association helped to legitimise the king's reign and provided him with significant support from the cult and its priesthood, which grew significantly in power and influence throughout the period. Ideology of kingship – divine birth, oracles, sed festival, opet festival Building program – king dedicates temples to Amun, king’s conquests provide resources for building from booty, tax and tribute Warfare and conquest – claims Amun inspires military campaigns, gives Amun credit for victories, dedicates booty from conquest to Amun Relationship with priesthood – Amun’s cult is state cult of Egypt, Great Royal Wife holds the title of God’s Wife of Amun, priesthood gains status from wealth from king’s dedications’ 4. Overview of religious beliefs and practices ● ● Religious myths and There are the gods, pharaoh beliefs were based upon a combination of polytheists, a belief in the afterlife. 2 main types of temples - cult temples or mansions of and the other being the mortuary temples of each Background and rise to prominence: 1. Family background Hatshepsut was the member of the Thutmosid line of kings of the early New Kingdom period. She was the daughter of Thutmose I and his chief Queen Ahmose. Little is known about the background of Queen Ahmose. She has the title of 'God's wife of Amun'. ● Relief of Hatshepsut as the consort of Thutmose II from the Temple of Amun at Karnak. She is wearing the vulture cap, the traditional headdress of the Great Royal Wife. Comparison of genealogy of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III: ● ● HATSHEPSUT: ○ Father – the mighty Thutmose I (who claimed to have got as far as the Euphrates River with his army) ○ Great-grandfather was Ahmose (who had liberated Egypt from Hyksos rule) ○ Directly in the royal blood line, daughter of the ‘Great Royal Wife’ THUTMOSE III: ○ Almost a commoner ○ Son of a concubine from the harem ○ His father (Thutmose II) was himself only half-royal Hatshepsut’s relation to Thutmose III – step mother, aunt and mother in law and also 20 years older. How did Hatshepsut’s family background contribute to her rise to power? Thutmose I – her father who is well respected from his military campaigns. Queen Ahmose – her mother who as the Great Royal wife. Possibly the sister of Amenhotep I – further royal blood. (She may be daughter of Ahmose and Ahmose Nefertari who drove out the Hyksos) Thutmose II – half sister to Thutmose II and wife. Queen consort then a regent to Thutmose III. Power gained from Thutmose II’s death as Thutmose III was too young. She already had experienced from her queen consort role. 2. Claim to throne and succession Hatshepsut as queen and regent ● ● ● ● She proclaimed herself king during year 2 to year 7 of Thutmose III’s reign She later adopted a horus name, or royal name of the king She was already using her throne name, Maat-ka-re, by year 7. A pottery seal, found in the tomb of Senenmut’s mother dated to regnal year 7, refers to Maat-ka-re. On the walls of the temple at Semna in Nubia, constructed in the 2nd year of Thutmose III, there is not a trace of Hatshepsut’s regnancy in the original sculptures. What are the dates of her accession? ● ● Several pottery jars or amphorae were found dated to ‘year 7’, one which bore the seal of the ‘God’s wife Hatshepsut’ and 2 which are stamped with the seal of ‘The Good Goddess Maatkare’ by year 7 of her regency she was acknowledged to be a king of Egypt Although she may have believed, even in childhood, that she deserved to wear the double crown in her own right there is no evidence that while her husband was alive she was anything other than a conventional queen consort. There are at least 3 pieces of evidence to support this statement: 1. 2. There was nothing unusual in her titles – King’s Daughter, King’s Sister, God’s Wife of Amun and King’s Great Wife. She ordered the construction of a tomb, suitable for a queen, hidden away in a valley several kilometers from the Valley of the Kings 3. She is shown on a stela standing ‘in approved wifely fashion’ behind her mother, and her husband Thutmose II who is facing Re. However, there is one interesting feature of this stela. It was inscribed during the reign of Thutmose II and yet Ahmose, is referred to as King’s Mother. Ahmose was the mother of Hatshepsut, not Thutmose II. This evidence has contributed to the theory that perhaps Hatshepsut saw herself quite early on as having a legitimate claim to the throne. Despite her apparent low profile during her regency with Thutmose III, the evidence points to the fact that from the beginning she was well and truly in full control of the government. Ineni’s inscription gives a contemporary comment on Hatshepsut’s control of the state: ‘…the Divine Consort, Hatshepsut, settled the affairs of the Two Lands by reason of her plans…’ Egyptian Co-Regencies Conventional Hatshepsut and Thutmose III Reigning pharaoh takes an uncrowned junior partner to ensure the succession and train the future pharaoh. Thutmose III, young reigning pharaoh, does not take a partner but his senior Hatshepsut makes herself crowned co-regent. Reigning pharaoh takes seniority in co-regency Hatshepsut as new pharaoh takes seniority in the co-regency over the reigning pharaoh. Juliette Bentley of Sydney University views that Hatshepsut intended to make herself pharaoh all along and establish a matriarchy. In evidence she refers to Hatshepsut holding her Sed festival 30 years after her father’s death. Cai Callender believes there was certainty a shared sovereignty, with Hatshepsut as senior regent and may have been double coronation. With the evidence of Thutmose III’s active role long before Hatshepsut’s death, seems to contradict Bentley’s view. How do you know about Hatshepsut? ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ Hatshepsut’s obelisk at Karnak ■ Horus name ■ ‘t’ feminine ■ ‘she made’ ■ ‘her monuments’ ‘Then his majesty [Thutmose I] said to them: ‘This daughter of mine Khnumetamun Hatshepsut – may she live! – I have appointed as my successor upon my throne…’ from the Coronation Scene at Deir el Bahri (the narrative of her legitimacy) A relief of Hatshepsut as a king kneeling before Amun Colossal statue of Hatshepsut (full appearance of a male) The god Amun-Re with queen Ahmose at the conception of Hatshepsut Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple at Deir el Bahri – ■ Includes expedition to Punt scenes ■ Hatshepsut’s conception, birth and coronation scenes ■ She encouraged worship of various gods Limestone bust of Hatshepsut as Osiris – a portrait from her mortuary temple at Deir el Bahari. She is depicted as ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ the male god Osiris, with whom all kings are identified with after death. The co-regency: ‘Identical Thutmosids: Hatshepsut Leading Thutmose III ‘Lord of the two lands’ These two are ruling side by side. Scenes from the expedition to Punt (Deir el Bahari) Hatshepsut as a man (Red Chapel, Karnak ‘I have raised up what was dismembered, even from the first time when the Asiatics were in Avaris of the north land…’ from Hatshepsut’s inscription at Speos Artemidos An inscription from a block of her Red Chapel at Karnak temple which refers to the proclaimation of an oracle predicting Hatshepsut’s accession. It is dated to year 2 of an unnamed king’s reign. One amphora is inscribed with the date ‘Year 7’ and the name of Hatshepsut with her ‘God’s wife of Amun’ title and no pharaonic title. Two more amphorae had sealing stamped with Maat-kare but were undated. Statuary and reliefs show her in a shendyt kilt, the nemes headdress with its uraeus and khat head cloth and false beard The Coronation Inscription: ● ● ● ● ● ● ● Gives details of the revelation of young Hatshepsut’s royal status The inscription consists of a number of sections in which Hatshepsut emphasizes her political right to the throne because Thutmose I chose her. Thutmose I presents her to the court and nominates her as his co-regent and intended successor ‘…This is my daughter KhnemetAmen Hatshepsut, living. I put her in my place.’ – complete fiction as there is no evidence to show that Thutmose I ever regarded Hatshepsut as his formal successor. Inscribed on outside wall of the Red Chapel at Karnak hints that the political situation may have already undergone a profound change. Details of Hatshepsut’s coronation at Karnak are included in a 3rd person narrative carved on several blocks which must have originally formed part of a wall of the Red Chapel. It is undated. Ignores the rule of Thutmose II ‘When she was still in the womb of her mother, all lands and countries were in her possession.’ Reliability: ● ● ● A number of scholars have said that it is propaganda to justify her accession ● Rejection of authenticity as it is taken word for word from the account of the coronation of Amenemhet III of the Middle Kingdom. ● Hatshepsut’s 2 brothers – Amenmose and Wadjmose – did not become king so they may have died before Thutmose I – he had no male heir. The monarchical system of the New Kingdom appears matrilineal: the ruler had to be the son of a first queen, a lesser queen, or husband of a daughter of a first queen. Her reign as king could have been seen as a legitimate element in the dynastic process of ensuring a stable and smooth succession to the throne of a ruler from within the Thutmosid royal family. This would also help to explain Thutmose III's apparent acceptance of his junior position within the coregency for as long as he did. -Divine Birth and coronation reliefs ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● To further substantiate her claim to the throne, Hatshepsut employed propaganda. Claims to Divine Birth had become important for Egyptian rulers from the Fifth Dynasty onward and had helped establish their legitimacy to the throne. The reliefs at Deir el-Bahri depict the process of divine conception and birth The ‘divine birth’ scenes are shown in a series of reliefs on the middle colonnade at Deir el Bahri Relief one of the Divine Birth – ‘My soul is hers, my bounty is heres, my crown is hers, that she may rule the Two Lands.’ Hatshepsut's mother Queen Ahmose is shown being courted and impregnated by Amun in the form of Thutmose I; Amun goes on to prophesy her coming to a council of gods. After her birth, Amun legitimised her future reign by nominating her as king and saying, 'I will give her all the lands, all the countries.' Hatshepsut had a fictitious coronation ceremony also depicted on the colonnade at Deir el-Bahri The Divine Birth and Coronation inscriptions clearly demonstrated the importance Hatshepsut attached to her royal bloodline, especially Thutmose I. Hatshesput ordered that the tale of her own divine conception and birth be told in a sequence of images and escriptive passages carved on the north side of the middle portico fronting her mortuary temple. The doctrine of theogamy – the physical union of a queen with a god At Deir el Bahri temple, the story of Hatshepsut’s conception starts in heaven. Shown as a legitimate pharaoh – the naked infant is shown as a boy. How did she become Pharaoh? ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● By year 7 of Thutmose III’s reign, Hatshepsut had abandoned the title of ‘God’s Wife’ There is an inscription referring to her with full regal titles which dates from this year, and accompanying depictions of her in full male garb as pharaoh, while her daughter, Nefrure, now bears the title of God’s wife Earlier depictions dating from year 3 showing Hatshepsut as a woman, with a woman’s hairstyle, but wearing the double crown hairstyle, but wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt, which only the Pharaoh was entitled to wear. Hatshepsut holding her Sed Festival 30 years after her father’s death, as if her husband Thutmose II had never existed. She is more royal – daughter of the Great Royal Wife and Thutmose I. She had to win over the support – such as the High Priest of Amun, the Vizier and commanders of the army. Claimed it was the will of her father. Gradual evolution, a carefully controlled political manoeuvre Jubilee or sed-festival ● ● ● Recorded on the walls of both Karnak and Deir el Bahri temple Announced her jubilee during year 15 – 30 years after the death of her father. On walls of Deir el Bahri temple we see Hatshepsut and Thutmose I offering milk and water. 3. Political and religious roles of king and queen in early 17th and 18th dynasties Political: ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● many New Kingdom kings emphasised their military role Ahmose I drove out the foreign Hyksos and conquered Lower Egypt Power would eventually be delegated to groups of advisors and administrators Queen's had no official role in politics unless acting as coregent There were no feminine words for a reigning monarch. So in most of her inscriptions, Hatshepsut is referred to in both masculine and feminine forms – Her Majesty, King Maat-ka-re. She arranged for her daughter Neferure, to marry Thutmose III to give him legitimacy. Hatshepsut saw her vital task and achievement as the rebuilding and stabilising of Egypt after the explusion of the Hyksos Major difference between Hatshepsut and other reigning queens is that she adopted the role of pharaoh claiming godship and sovereignty over Upper and Lower Egypt. Religion: ● ● ● ● they associated themselves very closely with the Cult of Amun King is seen as the link between the gods and his people Son of Amun-Re Queens appear to have played a supportive role in religion 4. Marriage to Thutmose II Hatshepsut married her half brother Thutmose II who succeeded his father as king in 1512 BC (ESTIMATED). Thutmose II was not as active as his father in empire building, but there does appear to have been military expeditions to Nubia and Palestine during his reign. ● ● ● Thutmose II and Hatshepsut had a daughter – Neferure A stela from this time shows her with Thutmose II and mother Queen Ahmose, standing in front of a statue of Amun-Re On the death of Thutmose I, the throne passed to his son by a lesser wife, Mutnofret. This was Thutmose II, who was apparently younger than Hatshepsut and of less ‘royal’ lineage. He married his half sister Hatshepsut, thereby securing his right to the throne. The famous story of the vandalisation of her inscriptions and monuments, often blamed on Thutmose III does not hold up under close examination. The attack took place 30 years after her death (maybe Akhenaten). The vandalism does not coincide with evidence of Thutmose III’s attitude in Ineni’s tomb inscription. Career: 1. Titles and changes to her royal image over time ● ● ● ● ● ● ● In the first 2 years of her regency Hatshepsut appears to have performed the role expected of her as Queen Dowager Depicted on public monuments in subordinate roles to her stepson Thutmose III She was in command - 'Hatshepsut settled the affairs of the two lands by reason for her plans' – Ineni She was careful to never appear subordinate to Thutmose III It is possible that Thutmose III did not regard his own right to the throne as automatic. His need to cite an oracle of Amun is support of kingship is certainly unusual. Since Thutmose III was between 3 and 6 years old, the Great Royal Wife, Hatshepsut, became regent for him and his wife. It is perfectly possible that the vast majority of the population, illiterate, uneducated and politically unaware, were indeed confused over the gender of their new ruler. There is absolutely no evidence to suggest that she suddenly came out as a transsexual, a transvestite or a lesbian. Image of Hatshepsut ● ● ● ● ● ● Red Granite Statue as a royal woman – ○ Wearing the nemes headdress of the king – however her figure and face are those of a woman Painted limestone sphinx ○ One of a pair which stood either side of the first flight of steps at Deir el Bahri with the inscription ‘Maat-kare, beloved of Amun, given life, forever.’ ○ She wears a false beard, royal nemes and a uraeus (broken off) ○ The sphinx was the traditional symbol for NKE warrior pharaoh ○ Feminine appearance Painted limestone bust ○ Portrait as Osiris found at Deir el Bahri (pharaohs are shown as Osiris after death) Red Granite Sphinx ○ Typical warrior pharaoh ○ Less feminine and wears royal headdress, uraeus and false beard Kneeling statue ○ Formal, shows Hatshepsut in full regalia, kneeling and offering 2 vases ○ Identical to a later statue of Thutmose III – apart from the name carved Colossal statue as a male monarch ○ Full male dress, with the pleated skirt of a pharaoh and a male body ○ Red granite ○ Formal stance Stages of her royal image Stage Features One ● In the first two years of her regency, Hatshepsut appears to have performed the role expected of her as Queen Dowager ● She retained her titles as Thutmose II’s wife and was depicted on public monuments in subordinate roles to her stepson Thutmose III Two Three ● It appears that she was well and truly in command of the machinery of government ● Evidence supporting this is found in the tomb of Ineni: ‘Hatshepsut settled the affairs of the two lands by reason of her plans.’ ● After two year, Hatshepsut’s titles and royal image began to change and reflect those of a male ruler ● She retained her female characteristics and was depicted in art with soft facial features and feminine physical attributes ● The final stage saw Hatshepsut assume male characteristics with the full regalia of a king ● She wore the shendyt (kilt), false beard, made offerings to the gods and was often depicted as the god Osiris who wore the regalia of an Egyptian king ● Her titles also underwent change over time, eventually becoming those of a king ● As queen, she was known as ‘king’s daughter’, ‘king’s sister’, ‘king’s great wife’ and ‘god’s wife of Amun’ ● As regent she retained her original titles but the change was signified by the new title – ‘Mistress of the Two Lands’ ● By the time she had evolved into a king, her titles had changed dramatically ● She now acquired full pharaonic titles and male regalia ● Her ‘great names’ included ‘Horus, Mighty of Kas’, her throne name ‘Maatka-re’, and her personal name ‘KnemetAmun-Hatshepsut’ ● Other titles included ‘Two ladies Flourishing of Years’, ‘Horus of Gold’: ‘Divine of Diadus’, ’King of Upper and Lower Egypt’, ‘Lord of the Two Lands’ , ‘Daughter of Re’ ● By year 7, her image and titles reflected her power and status ● There must have been no doubt that Hatshepsut now ruled as senior pharaoh in the co-regency 2.Foreign policy - military campaigns and trading expedition to Punt The Great Speos Artemidos Inscription What does Hatshepsut claim in this inscription? ● rebuilt the temple of the Lady of Cusae to protect her city ● ● ● ● made Pakhet’s temple worthy ‘I have raised up what was dismembered.’ Banished those who disrespect the gods (Hyksos) ‘My command stands firm like the mountains.\ What achievements does she emphasise? ● ● ● Her army has become possessed of riches since she arose as king Sculpted the image of the Lady of Cusae in gold She made Pakhet’s temple worthy Why would she make these claims? ● ● ● To show that she is a rightful pharaoh Emphasis her power Strong and successful Military campaigns 1) How have interpretations of Hatshepsut’s military campaigns changed over time? Provide quotes. ● ● ● ● Fragmentary evidence points to several campaigns. In the Speos Artemidos inscription she emphasizes her military role by referring to upgrading the army and by portraying herself as the traditional warrior pharaoh. Few today would claim, as John Wilson did in 1951, ‘she records no military campaigns or conquests’ or as Sir Alan Gardiner did in 1961, that her reign ‘had been barren of any military enterprise except an unimportant raid into Nubia.’ Current scholarship based on an assessment of a wider range of evidence recognizes that Hatshepsut pursued the traditional military policy of a ‘warrior pharaoh’ and conducted campaigns in Nubia and to a lesser extent in Syria-Palestine. The view proposed by Wilson when comparing the reigns of Thutmose III and Hatshepsut that ‘her pride was in the internal development of Egypt and in commercial enterprise’. 2) Suggest reasons why scholars of the 1950s and 1960s were dismissive of Hatshepsut’s military activities. (Tyldesley pg 137141) ● ● ● ● ● ● ‘Hers was a rule dominated by an architect, and the Hapusenebs, Neshis and Djehuty’s in her following were priests and administrators rather than soldiers.’ ‘triumphs of peace, not war’ Many feminist theorists and historians who view extreme violence and aggression as a purely male phenomenon Evidence is now growing to suggest that Hatshepsut’s military prowess has been seriously underestimated due to the selective nature of the archaeological evidence which has been compounded by preconceived notions of feminine pacifism. Egyptologists have assumed that Hatshepsut did not fight As so many of Hatshepsut’s texts were defaced, amended or erased after her death, it is entirely possible that her war record is incomplete. Location Deir el-Bahri mortuary temple at Djeser-Djesenu Details During the 19th century Naville had uncovered enough Evidence Provides us with evidence for defensive military references to battles to convince him that she embarked on a series of campaigns against her vassals. activity during her reign. Blocks originally sited on the eastern colonnade show the Nubian god Dedwen leading a series of captive towns towards Hatshepsut. Evidence of military campaigns in Nubia. Elsewhere in the temple she is portrayed as a sphinx, a human headed lion crushing the traditional enemies of Egypt. There is also written but badly damaged, a description of a Nubian campaign. ‘…as was done by her victorious father, the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Aakheperkare [Thutmose I] who seized all lands… a slaughter was made among them…’ Unofficial graffito from Sehel by Ti Confirms there was some fighting in the south. ‘I saw him [i.e. Hatshepsut] overthrowing the Nubian nomads…’ Tomb of Senenmut Evidence for at least one Nubian campaign ‘I seized…’ and further onwards ‘the land of Nubia’ Stela of Djehuty Stela by nobleman Djehuty says she hew Hatshepsut on battlefield collecting booty. ‘I saw the collection of booty by this mighty ruler from the vile Kush, who are deemed cowards, the female sovereign, given life, prosperity and health forever.’ Broken blocks at Karnak References to Nubian campaigns. ‘[Hatshepsut] who makes excellent laws and divine plans, who comes forth from the god, who commands what happens… [the Asiatic] being in fear and the land of Nubian submission.’ Deir el-Bahri mortuary temple “ “ “ 4) What conclusions can be drawn about Hatshepsut’s military activities? Pg 144 Tyldesley Hatshepsut’s military policy is perhaps best described as on of unobtrusive control; active defence rather than deliberate offence. She was certainly prepared to fight to maintain the borders of her country. Her military record is in fact stronger than that of Thutmose II. The fact that Hatshepsut did not need to fight may actually be taken as an indication of strength rather than weakness. The expedition to Punt: Significance of Hatshepsut’s expedition to Punt Political: ● ● ● ● Shown as a traditional pharaoh Highlights the prosperity and good government of the reign Promotes Hatshepsut as a successful pharaoh Ensures continued support of Amun priesthood Economic: ● ● Hatshepsut responds to demand for valuable exotic goods e.g. ebony, ivory, gold, cinnamon and other aromatic woods, animal skins and eye cosmetics Use of these goods as materials for temples, tombs, furniture and furnishing etc. Stimulated the economy Religious: ● ● ● An oracle of Amun is credited with initiating the expedition Myrrh trees planted in a garden at Deir el-Bahri dedicated to Amun Exotic goods from Punt dedicated to Amun, e.g. panther skins for priestly robes, baboons as symbols of Thoth Trade: ● ● On the façade of Speos Artemidos, Hatshepsut alludes to her trading activities The autobiographical inscription in the tomb of Thutiy points to the raw materials brought to Egypt from the south and northeast – gold, silver, copper, ebony and cedar Expedition to Punt…: ● ● ● ● Recorded as year 9 She had this expedition recorded in detail near the Birth and coronation reliefs on the walls of her mortuary temple Incense (kyphi) was burned in great quantities in cult temples Egyptians needed a continuing supply of exotic products for example: ○ Incense resins ○ Ebony ○ Live animals and animal skins ○ Ivory ○ Metals e.g. gold According to the reliefs in Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple: The expedition was organized and led by Nehsi, and accompanied by a small military contingent. ● ● ● ● ● Nehsi and his escort of soldiers carrying olive branches, ostrich fans, ceremonial axes to show peaceful intentions to Punt The people of Punt led monkeys and panthers and piled up loose myrrh resin Leaders of Punt are presented with bread, wine, fruit and meat Loading of the ships – ‘marvels of Punt’ Translations by Naville and Breasted: ○ Good woods ○ Myrrh resin ○ Ebony and ivory ○ ○ ○ ○ Green gold of Emu Cinnamon wood, khesyt wood, resin, eye cosmetic Apes, monkeys, dogs, skins of south panthers Natives and children Expedition to Punt features: ● ● ● ● Punt was a land of mysteries Punt was a major source of incense The expedition was originated from oracle to Hatshepsut from Amun Dedicated to Amun 3. Building programs: Deir el-Bahri, Karnak, Beni Hassan and tombs Hatshepsut's building program Research assignment Hatshepsut's top priority seemed to be her building program as she repeatedly refers to it. She built from the delt to Kush and outlined her policy in the text inscribed on the facade of a small rock-cut temple near Beni Hassan, which the Greeks referred to as Speos Artemidos. Her building policy appears to have involved: ● ● ● Repairing temples, chapels and sanctuaries neglected during the domination of the Hyksos, such as the temple of Hathor at Cusae, a temple for Min and the temple of Thoth at Hermopolis. Constructing new ones such as her mortuary temple at Deir elBahri; the Red Chapel, obelisks and pylon at Karnak; the barque sanctuary at Luxor and the cliff temple dedicated to the lion goddess, Pakhet at Beni Hassan Completing work begun by Thutmose II What do the following extracts reveal about the motivating factor behind her building policy? 'She made them as a monument for her father, Amun, Lord of Thebes, presider over Karnak...' 'I have done this with a loving heart for my father Amun...' Deir el-Bahri Djeser-djeseru (Holy of Holies) 1. What are the main architectural features of the mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri - including innovations and decorations? The mortuary temple of Hatshepsut was undoubtedly influenced by the style of the earlier temple at Deir el-Bahri, but Hatshepsut's construction surpassed anything which had been built before both in its architecture and its beautiful carved reliefs. The temple of Hatshepsut was built on three terraced levels, with a causeway leading down to her Valley Temple (now lost) which would have been connected to the River Nile by a canal. Gardens with trees were planted in front of the lower courtyard. The Red Chapel is part of these outstanding buildings: original in concept, it is unique in creation since it is probably the first 'prefabricated' in stone in the history of the world. The Red Chapel is constructed with the hlep of blocks of red quartzite and of grey diorite. 2. How do they differ from traditional New Kingdom temples like those at Luxor and Karnak? The Red Chapel was entirely preassembled on the ground. It is interesting to note that this process of assembly wouldn't be resumed subsequently in Egypt. 4. How does the decorative program at Deir el-Bahri support Hatshepsut's religious innovations? Hatshepsut showed her devotion to Amun and thanked him for having expressly appointed her, and one could say dubbed her, as legitimate Pharaoh in front of all the people. The Speos Artemidos Temple at Beni Hasan 5. What was the reason for the construction of this temple? They are dedicated to Pakhet. One of the temples bears a long dedicatory text of Hatshepsut with her famous denunciation of the Hyksos. 6. Where was it built? Why was this location unusual? It is located about 2 km south of the Middle Kingdom tombs at Beni Hasan, and about 28 km south of Al Minya. Hatshepsut’s building program: ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● She outlined her building policy in the text inscribed on the façade of a small rock-cut temple built at Beni Hassan (speos Artemidos) Her building policy appears to have involved: ○ Repairing temples, chapels and sanctuaries destroyed during the Hyksos e.g. Temple of Hathor at Cusae ○ Constructing new monuments such as her mortuary temple at Deir el Bahri, the Red Chapel Her architects – generally believed that Senenmut She initiated building projects as far as Cusae and Nubia There are clues as to which officials were responsible to her building programs found on statues, graffiti at excavation sites, reliefs and autobiographical texts in tombs Identified – Senenmut, Thutiy, Ineni On the façade of Speos Artemidos, she claimed to have ‘restored that which was in ruins’ Cult worship re-established New temples would serve as perhaps the greatest offering that a king could make to the gods Large stone building possessed the useful feature of allowing the monarch to exploit this billboard Her Tombs: 9. Why were two tombs built? Hatshepsut had begun construction of a tomb when she was the Great Royal Wife of Thutmose II, but the scale of this was not suitable when she became "king", so a second tomb was built. This was KV20, which was possibly the first tomb to be constructed in the Valley of the Kings. 10. What was found in the second tomb? At some point it was decided to inter her father, Thutmose I from his original tomb in KV38 into a new chamber below her own. Her original red-quartzite sarcophagus was altered to accommodate her father instead, and a new one was made for her. It is likely that when she died (no later than the twenty-second year of her reign) she was interred in this tomb along with her father. 11. What was innovative about the construction of the second tomb? Her original red-quartzite sarcophagus was altered to accommodate her father instead, and a new one was made for her. Construction of new monuments - Djeser-djeseru (Holy of Holies) ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ● ● ● Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple The magnificence of the site is captured in the words of archaeologist Naville in 1894 Created a garden for her divine father Amun-Re Painting of her accomplishments – divine birth and coronation, the expedition to Punt The purpose was also to: ■ Show dedication to Amun ■ Dedicate worship to other deities – Hathor, Anubis Evidence of the foundation of the temple ● The temple was inspired by Mentuhotep II, but she introduced a completely different type of rock-cut temple – carved from living rock ● Hypostyle hall ● Colossal statues of Osiris ● Central sanctuary to Amun Building at Karnak Hatshepsut initiated a renewed emphasis on building at AmunRe’s temple at Karnak. Throughout her reign, she embellished Amun’s temple at Karnak by: ○ Repairing the Middle Kingdom temple ○ Adding a pylon (eighth ○ The Red Chapel ○ Erecting 4 obelisks Obelisks: ● ● ● ● two of the original four still exist and one is still standing. The inscriptions on them announce that they were made of red granite with the pyramidions of fine gold. According to Alison Roberts, Hatshepsut claims that she made Karnak the sacred akhet Evidence suggests that Senenemut was responsible for the first pair The height and weight of the surviving obelisks reveal the manpower and skill that would have been required Propaganda: Inscriptions focus on her right to the throne, the glorification of Amun and her relationship with Thutmose I. The Red Chapel: ● ● ● Built a barque chapel at the Karnak temple Dedicated to Amun-Re Hatshepsut, not Senenmut, takes full credit for the transportation of the obelisks (shown at the Red Chapel) The Temple at Karnak ● The temple at Karnak was the major temple to the god Amun-Re ● ● Hatshepsut, in keeping with established tradition, extended it, adding four obelisks to Amen, various chambers, the ‘Red Chapel’ and the Eighth pylon. Completion of structures begun by Thutmose II The Temple of Karnak 8. What did Hatshepsut build to embellish the Temple of Karnak? (mention the Red Chapel, Hatshepsut's Suite, Pylon 8 and the Processional Way) The Red Chapel was initially destined to replaced a building dating from Amenhotep I, the Alabaster Chapel. The erection of the Red Chapel comes within the framework of a vast political program of the Pharaoh-queen, essentially centred on her concern ofr ecognition. Hatshepsut proceeds with the progressive occupation of the main sites of Karnak. Hatshepsut's suite - rooms surrounding the Karnak bark chapel. ● Speos Artemidos ● She endowed 2 temples dedicated to Pakhet (known as Speos Artemidos ● Here carved high above the pillars is where Hatshepsut makes the bold pronouncement of the policy of her reign; a policy of renewal and restoration ● She claims credit for ridding the land of the Hyksos and restoring the monuments ● Organised and supervised by Senenmut 4. Religious policy: devotion to Amun and promotion of other cults 5. Relationship with Amun priesthood. Officials nobles (Senenmut) Hatshepsut’s officials ● ● The backbone of her administration lay in the priesthood of Amun One of these was Hapuseneb, high priest of Amun, who was at one time in charge of the construction of the temple at Deir el Bahri Senenmut ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● Tutor of Neferure Was he Hatshepsut’s lover? – graffiti He first took office under Thutmose II Appears that he had financial management skills Contributed to the building of the temple at Deir el Bahri, as well as supervising the cutting and transport for 2 of her Karnak obelisks. Because of Senenmut’s undoubted eminence and the privileges he enjoyed some popular writers have claimed a sexual relationship between him and Hatshepsut. This was fuelled by vulgar graffito He left a vast number of statues of himself and built a large tomb In year 16 Hatshepsut’s workers were excavating a tomb for him. He was not her architect, but he would be enabled to employ the best architects His wealth increased – known from his mother Hatnofer’s tomb and his own. He appears to have been on intimate terms with the royal family – from inscriptions ● ● ● ● ● ● ● He disappeared from records about Year 16 of Hatshepsut’s reign He was a commoner Meyer maintains that he had no children and was a bachelor from: ○ He is shown only with his parent on the funerary stelae in his tombs (2) ○ He is shown alone in the scenes from the Book of the Dead in his 2nd tomb We know little of his early career, although a tomb inscription implies that he spent time in the army He appears among her officials before the death of Thutmose II The evidence for his status can be found in the inscriptions on; ○ A black diorite statue dedicated to Mut ○ Walls and funerary stelae of his tombs ○ The rocks at Aswan ○ Name stones from his tombs Great honors’ Hatshepsut gave him: ○ 80 titles ○ Erect statues ○ Engrave his name in her mortuary temple Other officials: Official Details Ineni Had served under Thutmose I. His tomb biography records favours awarded to him by Hatshepsut. In his tomb he wrote he was favoured by Hatshepsut. Ahmose Pennekhbet He was the nurse of Neferure in her early infancy from his tomb biography) Hapuseneb Was in charge of the Karnak and Deir el Bahri monuments and Hatshepsut’s tomb Thutiy Hatshepsut’s ebony shrine, metalwork on the obelisks and gold brought back from Punt. 6. Relationship with Thutmose III: co-regency and defacement of monuments ● ● ● They shared monuments and stelae, but her image and name were always in front of his. Punt reliefs on walls of Hatshepsut’s temple at Deir el Bahri – he is behind the queen. In a relief on a building inscription in western Thebes, Hatshepsut and Thutmose III are shown worshipping Amun-Re together. Once again, he is standing behind her and there is no mention of him in the inscription. ● ● ● Both Hatshepsut and Thutmose III are mentioned on a statue of the nobleman, Enebni and in the tomb of Thutiy. Later in Hatshepsut’s reign, Thutmose III appears to have taken a more prominent role in public affairs. On a stela found in Wadi Maghera in the Sinai the two kings are shown standing side by side offering to Hathor and Sopdu. By downgrading the exploits of Hatshepsut, he was bolstering the importance of his own. The fate of Hatshepsut: ● ● ● ● Although her mummy has never been found, there is no evidence to suggest that her death was anything but normal. Despite the lack of evidence, some writers, however, wish to make her end more dramatic Wilson and Steindorff and Seele believe that her life came to an abrupt and unnatural end probably during a coup by Thutmose III. Mertz suggests that as Hatshepsut grew older, some of her supporters may have felt that it was time to show their loyalty to Thutmose III. At the present time there is no evidence to suggest that she was either murdered or deposed by her co-ruler. Damage to monuments: ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● Hatshepsut’s names, titles and images were erased from the walls of the temples and replaced with those of her father, Thutmose I, Thutmose II and Thutmose III. Her name was absent from all later lists of kings. Dozens of her statues were smashed and dumped in a pit at Deir el-Bahri Her giant obelisks in the Temple of Karnak were enclosed behind a wall In many of Hatshepsut’s reliefs, the figure of Amun has been obliterated. This was obviously not done on the orders of Thutmose III since he continued to glorify Amun and surpassed Hatshepsut in his dedications to this god of empire. A king called Akhenaten introduced the worship of a form of the sun god called Aten. He may have ordered the mutilation of the images of Amun. It is believed that Ramesses II also ordered alterations to the inscriptions on Hatshepsut’s monuments. At Djeser-Djeseru her statues and sphinxes were torn down, smashed and flung into rubbish pits. The removal of a name and image of a dead person, occasionally called a damnation memoriae, served a dual purpose. It allowed the rewriting of history; it was also a direct assault. Naville had done recent analysis (1906) of the Chapelle Rouge – the defacement of Hatshepsut’s monuments occurred late in his reign – possibly not before Year 42. Why would Thutmose III wait 20 years before venting his hatred on his co-ruler? The obelisks adapted (like the Chapelle Rouge)to fit in with Thutmose III’s building plans? Hatshepsut’s reign might possibly be interpreted by future generations as a grave offence against maat. Wounded male pride may also have played a part in his decision to act ● ● ● Thutmose III had always to consider the possibility that the first successful female king might establish a dangerous precedent. One dynastic queen regent – Queen Sobeknofru existed, but her reign was a failure, suggesting that a woman was incapable of holding the throne in her own right. It is only the image of Hatshepsut as king which have been defaced. Evaluation: 1. 2. 3. 4. impact and influence on her time assessment of her life and reign legacy ancient and modern images and interpretations Hatshepsut’s impact and influence on her time ● In order to evaluate Hatshepsut’s influence on her time, we must consider her achievements in relation to the criteria of traditional pharaonic policy, as well as to new initiatives. Traditional New Kingdom pharaohs engaged in the following: ○ Promotion of Amun-Re ○ Self promotion ○ Waging successful military campaigns ○ Maintaining Egypt’s prosperity ○ Building programs ○ Ensuring the succession Activity Hatshepsut became regent for the young king (Thutmose III), managing the affairs of Egypt for him until he was old enough. Her divine birth Traditional Yes, this was carried out by Tetisheri for Ahmose when his father Seqenenre Tao II died. Her coronation as king Yes, for rightful rulers to the throne. She was female. Military activity Yes, a ruling pharaoh was expected to carry out military activity in Innovative Yes. Of special importance is the role played by Amun in Hatshepsut’s conception. Significance An inscription from the tomb of Ineni, records her role as regent. Shows that she started out as a traditional regent. She was keen to stress her religious claim as both the spiritual and physical daughter of the god. She emphasises her political right to the throne because of her father Thutmose I chose her as heir. She did not exactly extend the borders, she carried out more of a defence role. Depiction as a ‘warrior pharaoh’ order to defend and extend the borders. Yes, a pharaoh was seen to be strong. Yes, she is a woman. Warriors were seen to be male. This is seen to be part of a pharaohs reign – to be depicted as a warrior pharaoh. Assessment of Hatshepsut’s life and reign 1. A strong and capable ruler who consolidated the 18th dynasty of the Thutmosids and reinforced the legitimacy of the line through its alleged relationship to the god Amun 2. She was largely responsible for the elevation of the god Amun to supreme status 3. Though it was unusual for a female to reign as Pharaoh, and as co-regent with her stepson, it was no unprecedented in Egyptian history 4. She maintained her father’s conquests by further military action, but does not seem to have embarked on any additional conquests to further extend Egypt’s boundary, whereas her co-regent and successor Thutmose III did. 5. Her policies appear to have been more motivated by a plan to maintain security, and were therefore basically defensive, whereas his were blatantly aggressive. 6. The so-called ‘Feud of the Thutmosids’ has little real evidence to support it, apart from the destruction of her monuments, and even this may be work of a later pharaoh 7. The foundation of a strong, prosperous and united Egypt which she helped to create enabled Thutmose III to embark on his risky campaign of conquest. Hatshepsut’s legacy ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● Legacy – something left to or handed down to someone, a consequence of some action or event. Glorified and dedicated extensively to Amun Extensive building program – Recalled former glory. Instilled confidence. Provided employment. Contributed to the prestige of the Amun priesthood, priests of Amun wielded great power as wealth of the temple increased. Trading expeditions – provided raw materials, increased wealth, widened contacts Military campaigns – secured borders, controlled nubia, equipped army Created a stable, prosperous and secure Egypt Allowed Thutmose to campaign beyond Egypt for 17 years Growth of an empire – increased wealth and power of Egypt Later pharaohs, lead from her Divine Birth cycle of reliefs and inscriptions and incorporated similar themes in their own temples. Introduction of oracles, the development of personal piety and the public pageantry of festivals ● Her innovations in architectural design (e.g. the hypostyle hall) became standard features in later New Kingdom temples. Questioning historians: JA Wilson – ‘She records no military campaigns or conquest; he became the great conqueror and organiser of empire. Her pride was in the internal development of Egypt and in commercial enterprise; his pride was in the external expansion of Egypt and in military enterprise. A Gardiner – ‘…her ambition was by no means dormant, and not many years had passed before she had taken the momentous step of herself assuming the Double Crown.’ G. Steindorff and KC Seele – ‘It must have been very much against his will that the energetic young Thutmose III watched from the side lines the high-handed rule of the ‘pharaoh’ Hatshepsut and the chancellorship of the upstart Senmut…’ Modern images and interpretations of Hatshepsut Modern representations of Hatshepsut reflect a wide range of changing perspectives from the early days of Egyptology to the present. The historiographical debate has tended to focus on her gender and the extent to which she was a legitimate and/or effective ruler. Interpretations include: ● A wicked step-mother usurping the throne from the rightful heir ● An ambitious power-seeker ● A loyal and dutiful daughter ● An intelligent and competent ruler ● A dynastic visionary, grooming her own daughter for the succession Redford ‘Hatshepsut showed herself to be an imaginative planner possessed of rather original taste…’ Tyldesley ‘…shows Hatshepsut to have been an unexceptional and indeed almost boringly conformist wife and mother paying due honour…’ Dorman ‘Both Ineni’s biography and Senenmut’s graffito indicate that Hatshepsut was the effective ruler of Egypt from the death of her husband…’