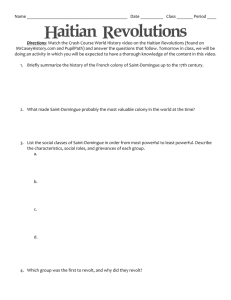

Haitian Revolution Timeline

advertisement

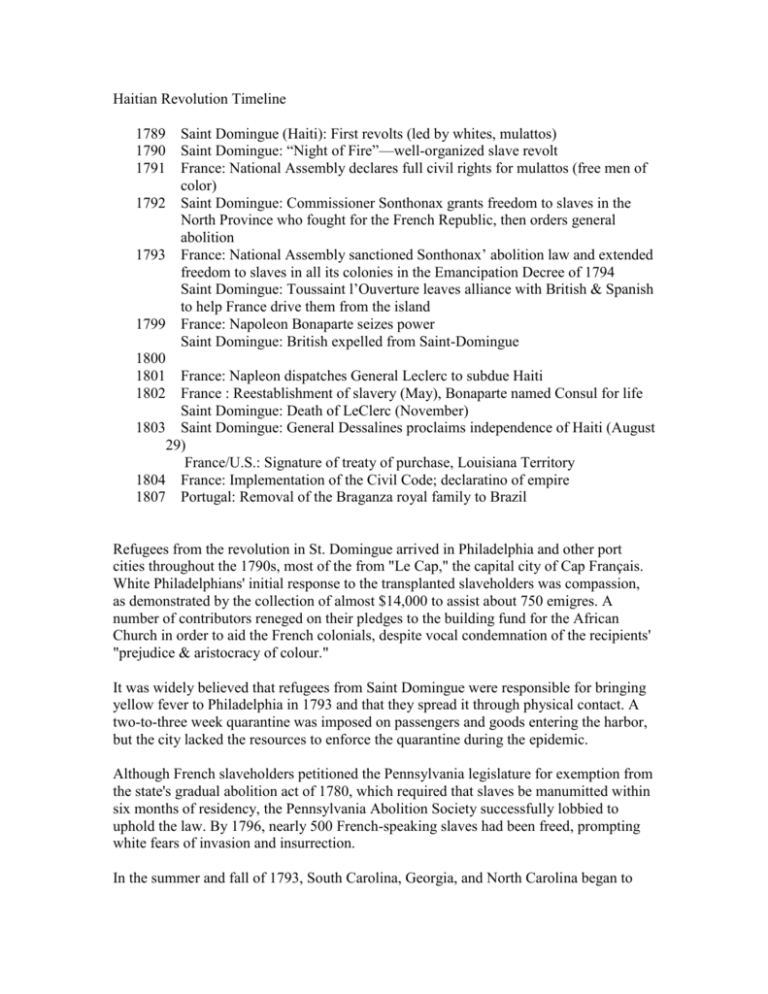

Haitian Revolution Timeline 1789 1790 1791 1792 1793 1799 Saint Domingue (Haiti): First revolts (led by whites, mulattos) Saint Domingue: “Night of Fire”—well-organized slave revolt France: National Assembly declares full civil rights for mulattos (free men of color) Saint Domingue: Commissioner Sonthonax grants freedom to slaves in the North Province who fought for the French Republic, then orders general abolition France: National Assembly sanctioned Sonthonax’ abolition law and extended freedom to slaves in all its colonies in the Emancipation Decree of 1794 Saint Domingue: Toussaint l’Ouverture leaves alliance with British & Spanish to help France drive them from the island France: Napoleon Bonaparte seizes power Saint Domingue: British expelled from Saint-Domingue 1800 1801 1802 France: Napleon dispatches General Leclerc to subdue Haiti France : Reestablishment of slavery (May), Bonaparte named Consul for life Saint Domingue: Death of LeClerc (November) 1803 Saint Domingue: General Dessalines proclaims independence of Haiti (August 29) France/U.S.: Signature of treaty of purchase, Louisiana Territory 1804 France: Implementation of the Civil Code; declaratino of empire 1807 Portugal: Removal of the Braganza royal family to Brazil Refugees from the revolution in St. Domingue arrived in Philadelphia and other port cities throughout the 1790s, most of the from "Le Cap," the capital city of Cap Français. White Philadelphians' initial response to the transplanted slaveholders was compassion, as demonstrated by the collection of almost $14,000 to assist about 750 emigres. A number of contributors reneged on their pledges to the building fund for the African Church in order to aid the French colonials, despite vocal condemnation of the recipients' "prejudice & aristocracy of colour." It was widely believed that refugees from Saint Domingue were responsible for bringing yellow fever to Philadelphia in 1793 and that they spread it through physical contact. A two-to-three week quarantine was imposed on passengers and goods entering the harbor, but the city lacked the resources to enforce the quarantine during the epidemic. Although French slaveholders petitioned the Pennsylvania legislature for exemption from the state's gradual abolition act of 1780, which required that slaves be manumitted within six months of residency, the Pennsylvania Abolition Society successfully lobbied to uphold the law. By 1796, nearly 500 French-speaking slaves had been freed, prompting white fears of invasion and insurrection. In the summer and fall of 1793, South Carolina, Georgia, and North Carolina began to pass laws that prohibited the entry of free blacks from the West Indies and called for the deportation of slaves who had previously immigrated. Five years later, Pennsylvania Governor Thomas Mifflin issued a similar prohibition, and also contemplated barring the landing of "French negroes" in surrounding states and the entry of French slaveholders into Pennsylvania. Whites feared the slaves the refugee planters brought with them. They viewed all the Caribbean slaves as potential rebels and were terrified by the vision of destruction they might inspire among North American slaves. In 1800 that vision almost became a reality, as Gabriel's intended insurrection was discovered and exposed, and white fears increased.