transplant news webinar transcript

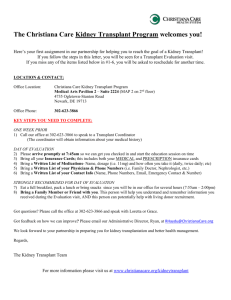

advertisement