The ancient Greeks had plays with songs, and Roman comedies

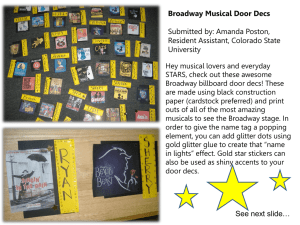

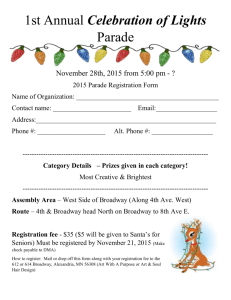

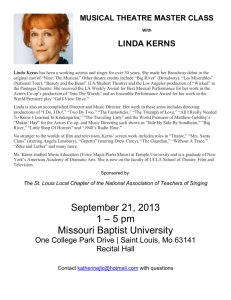

advertisement