Professional Paper - Institute for the Built Environment

advertisement

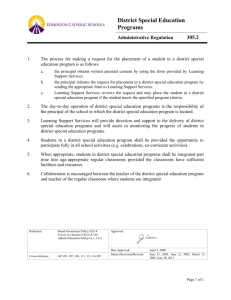

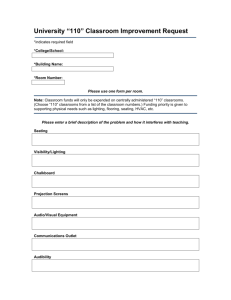

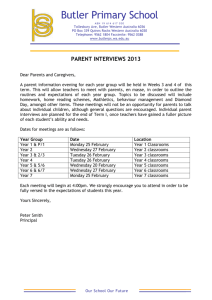

Professional Paper AN ASSESSMENT OF GREEN DESIGN IN AN EXISTING HIGHER EDUCATION CLASSROOM: A CASE STUDY Submitted by Annie Lilyblade Department of Construction Management In partial fulfillment of the requirements For Degree of Master of Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Fall 2005 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 Review of Literature 5 The Case Study at a Higher Education Institution: A Remodel of an Existing Classroom 5 Purpose 14 Glossary of Terms 14 Methodology 15 Findings 19 Discussion and Conclusion 29 References 34 Appendices LEED for Commercial Interiors Guidelines and Credits The Talloires Declaration The Guggenheim LEED Checklist 36 2 Abstract The purpose of this case study was to assess the quality of a classroom remodel in a higher education institution. Both the teaching and learning environments as well as the level of green design integration were assessed. The methodology for this qualitative study involved five steps of data collection including an existing pre-design survey, interviewing five members of the initial design team, interviewing two faculty members, a post-design survey, and an assessment of the level of sustainability utilizing the LEED – CI (Commercial Interiors) rating system. The data collected were to assess both the perceptions of the design team and the end users. Overall, results from the data collected demonstrated end-users satisfaction as well as that the classrooms meet the criteria of a sustainable classroom. The case study proved to be a concerted effort by an integrated team. The project results now teach others how to provide sustainable sites, increase water efficiency, improve overall energy performance, and how to use of sustainable materials and resources. Furthermore, these findings show how to decrease construction waste, create a healthy indoor environment, and how to create an optimal teaching and learning environment. 3 Introduction The built environment, through design, construction, and operation practices, generates a highly significant impact on the earth and its resources. Aspects of buildings that affect the natural environment include overuse of energy, air pollution, and generation of waste resulting in expansion of landfills. Beginning in the mid-1980s, several design professionals associated a building’s indoor environment with a building’s design and construction. Early observations, including issues such as sick building syndrome related to poor indoor air quality, overuse of electric light, and poor daylighting, raised public awareness and opened the door for future sustainable design values. Advocates of healthy indoor environments indicated that buildings could improve human performance, pay back a client’s investment, and provide an overall healthy environment (Coleman 2002). The healthy building movement evolved into what is known today as sustainable design. Sustainable or ‘green’ design implements a comprehensive “systems” mode of thinking when designing built environments which, if followed, preserves our resources, raises environmental sensitivity, promotes higher resource efficiency, and allows for cultural and community responsiveness (USGBC, 2003). This concept affects many aspects of society such as agriculture, transportation, manufacturing, and construction. Green building practices, those that reduce impacts the built environment has on nature, contribute to sustainability within design and construction practices. 4 Today, many higher education institutions have begun to implement sustainable design practices on campus. Several institutions have signed the Talloires Declaration, an official statement made by university administrators to commit to sustainability in higher education, and to incorporate sustainability and environmental literacy in teaching, research, operations, and environmental outreach. The Talloires document has been signed by over 300 university presidents and chancellors from more than 40 countries (ULSF, 2005). Using sustainable design principles, this paper will assess the remodel of a classroom located on a higher education campus, whose administration has signed the Talloires Declaration. Review of Literature With the movement towards sustainable design, the USGBC (United States Green Building Council) developed the LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) guidelines which offered a rating system to quantify a building’s level of sustainability. LEED was created to define ‘green building’ by establishing a common standard of measurement; to promote integrated, whole-building practices; to encourage and recognize environmental leadership in the building industry; to raise consumer awareness of green building benefits; and, to transform the building market (LEED, 2000). The rating system is organized into five categories including sustainable sites, water efficiency, energy and atmosphere, environmental quality, and materials and resources. Using the LEED rating system, model classrooms can be developed as instruments for educational institutions to expose and educate the campus communities about sustainability and green building. 5 One method to educate the campus community about sustainable design is to incorporate green building principles into teaching and learning environments. We have assumed, wrongly I think, that learning takes place in buildings, but that none occurs as a result of how they are designed or by whom, how they are constructed and from what materials, how they fit their location, and how well they operate . . . buildings have their own hidden curriculum that teaches as effectively as any course taught in them (Orr, Earth in Mind, p ll3). David Orr, professor of Environmental Studies at Oberlin College, emphasizes that universities are here to teach, and the teaching and learning process should be supported by our buildings’ architecture and settings in which classes are taught. A number of universities, along with primary and secondary schools, have heeded Orr’s call by designing and constructing buildings that teach. It’s tough to dispute the overwhelming benefits that come from using schools as instruments of learning…countless studies have been conducted linking the architectural characteristics of schools to attitudes, behaviors and achievements…studies released by Cornell University showed direct connections between educational architecture and high performing students (Cunningham, 2002). When designing a classroom it is essential that the environment enhances and promotes learning, provides comfort for all users, promotes a healthy environment, accommodates the needs of all occupants so every student has an opportunity to learn, provides for health, safety, and the security for all users, and makes effective use of all available resources (Niemeyer, 2003, Smarter, 2003, Babey, 1991). In an effort to enhance levels of design in a college classroom, a framework has been developed by education researchers. Three different research efforts since 1991 have identified seven design principles that should be addressed during schematic design and design development 6 phases of a classroom design process. The seven principles identified are to empower faculty, emphasize flexibility, and to encourage student interaction, simplicity, connectivity, reduced cost, and attention to classroom details (Niemeyer, 2003, Smart, 2003, Babey, 1991). The design process for educational environments can be developed using aspects of environmental psychology, such as the study of relationships between individuals and their physical environment (Gifford, 1997). There are four assumptions about educational environments related to a psychological foundation. First, the physical environment of a classroom can either contribute to the success of students, or inhibit their learning. These physical aspects include direct factors, such as crowding or noise levels. Secondly, the effects of physical environments on learning are often affected by other social, psychological, and instructional variables. Third, a learning environment should match teaching objectives and styles, student learning styles, and the social setting. The fourth principle acknowledges that learning is optimized when physical environments are treated in the same focused way that curricular material and teacher presentations are created (Graetz, Goliber, 2002). Since the late 1990s, school districts and campus committees have begun to embrace the principles of sustainable design. Green design and construction processes contribute to several potential benefits for a classroom environment. The list of benefits includes improved indoor air quality, reduced energy cost for heating and cooling, and conservation of resources through the use of recycled or reused materials, coupled with construction waste recycling. A building’s green design classroom can provide the tools to educate students about sustainability in addition to reducing its environmental impact. 7 A related trend in sustainable school design involves the creation of high performance school buildings. High performance designs share many similarities of sustainable design. There are three main goals involved in the creation of a high performance school. The first seeks to provide a healthy and productive environment for students and teachers. This goal is addressed by providing high levels of acoustic, thermal, and visual comfort, large amounts of natural daylight, good indoor air quality, and a safe and secure environment. The second goal seeks to create a design that is cost effective to operate and maintain. Energy analysis tools that optimize energy performance and life cycle cost methods should be used to reduce the total cost of operations. A building commissioning process that evaluates that the building is designed, constructed, and operated as intended, helps to ensure the potential of a healthy, productive interior environment. The third goal is to focus on sustainability by integrating energy conservation, and ideally, renewable energy strategies. To satisfy this goal, high performing mechanical and lighting systems, environmentally-responsive site planning, sustainable materials and products, and water-efficient design ideas are incorporated. Creating a design that encompasses all of these recommendations requires an integrated and whole systems approach, to the design process. By addressing each of the three goals, a building can be optimized to achieve long-term value and performance. A high performing, sustainable school facility enhances teaching and learning, reduces operating costs, protects the environment and is an asset to the entire community (High Performance Schools, 1999). 8 College and university campuses around the country are beginning to incorporate environmental principles into course curriculum and facility operations. Several universities have signed the Tallories Declaration, publicly acknowledging that they are promoting a sustainable future. In 2001, former Colorado State University president Al Yates, signed the Tallories Declaration. This new initiative is designed to extend beyond the creation of new programs to develop "greening" of campuses. These initiatives often include "environmental audits" that examine the environmental impacts of university operations in solid waste, water, energy, and transportation. “Colleges and universities wield incredible power – and yet, at least in terms of the environment, most have not wielded well. Our institutions of higher learning provide the knowledge that will guide our future architects, engineers, policy makers, community activists, industrialists, mothers, fathers, potential teachers, all. Nonetheless, with only a few noteworthy exceptions, most colleges and universities fail to educate their students in the environmental ramifications of their fields of study. We will persist in designing buildings that are energyinefficient, products that pollute, and systems that throw off waste, we will go on doing all these things and more, as long as our educators fail to teach their students that it does not have to be this way. There is a better and less expensive way. Ultimately, design is an expression of intent. What is needed is thought and planning about function, aesthetics, conservation, efficiency; in other words, intent.” Teresa Heinz – delivered to the Campus Earth Summit At Brown University, the ‘Brown Is Green’ program uses student research, administrative structure, and on-going education, to reduce the environmental impacts of specific operations, including water and electrical consumption and solid waste management. The Center for Regenerative Studies at California State Polytechnic University, uses solar energy and natural sewage treatment to support housing, classroom, and research facilities for 90 students, faculty, and staff. At Georgia Institute of Technology, the Center for Sustainable Technology introduces 9 ecological principles to the design of new and existing buildings. South Carolina's three research universities–Clemson University, the University of South Carolina , and the Medical University of South Carolina – have created a collaborative sustainability initiative that involves representatives from state agencies and other participants (Greening, 2004). The Campus Earth Summit Initiatives for Higher Education, a project of the Heinz Family Foundation, was designed to help develop and recommend a technique for developing a Blueprint for a Green Campus. Ten recommendations came out of the Campus Earth Summit. 1.) Integrate environmental knowledge into all relevant disciplines, 2.) Improve undergraduate environmental studies course offerings, 3.) Provide opportunities for students to study campus and local environmental issues, 4.) Conduct a campus environmental audit, 5.) Institute an environmentally responsible purchasing policy, 6.) Reduce campus waste, 7.) Maximize campus energy efficiency, 8.) Make environmental sustainability a top priority in campus land-use, transportation, and building planning, 9.) Establish a student environmental center, and 10.) Support students who seek environmental responsibility. Each of these recommendations can be evaluated when applying them to a campus classroom (Blueprint, 1995). The Case Study at a Higher Education Institution: A Remodel of An Existing Classroom Picture 1: Prior to remodel Picture 2: After remodel Picture 3: After remodel 10 Located along the front range of the Rocky Mountains and identified as a Carnegie 1 research institution, Colorado State University forms the setting for a case study analysis of a classroom remodel. The Green Classrooms of Guggenheim Hall pioneered initial efforts to the campus declaration to provide a sustainable campus. Guggenheim Hall, one of the first buildings built on campus, was constructed in 1926. Students in the Facilities Planning and Management graduate level course were given a rare opportunity to incorporate design ideas through charrettes and research for the first ‘green’ classrooms on the CSU campus. The goal was to create a positive teaching and learning atmosphere while reducing the impact that traditional construction has on the environment. In the first phase of the design, students and other campus members participated in a design charrette - an intensive, integrated, group workshop, to outline common project goals. To compile a list of design features that needed attention, the graduate class administered a survey to students who used the existing classrooms. From this list, the graduate students began researching materials and techniques to be used in developing a sustainable classroom design. The students then formally presented the research to CSU Facilities Management, the Campus Classroom Review Board, and the Construction Management faculty and administration. After final approval by the University administrators, the project was handed over to the faculty and elected students to decide which features, based on feasibility and cost, from the research proposals were best for the renovations. Two class participants, who were LEED accredited professionals, coordinated the project through completion. 11 Each element of the design was evaluated for functionality, sustainability, aesthetics, and cost. Ideas and materials were evaluated by the various stakeholders. In addition, the students used the LEED – CI (Commercial Interiors) rating system as an evaluation tool to determine the sustainability of each classroom suggestion. The ideal products were durable, contained recycled content, were low in VOCs (volatile organic compounds), energy efficient, and were natural and / or locally manufactured products. The project coordinators then created ‘sole source’ descriptions for the products to enable the Purchasing and Facilities Management departments to procure sustainable products. The Green Classrooms of Guggenheim Hall have several sustainable features. The existing fluorescent fixtures were taken down, cleaned, touched up with new paint, and were retrofitted with energy-saving ballasts and bulbs. Re-orientation of lighting contributed to a significant decrease in the amount of fixtures in each room. Dimmable, energy efficient track lighting and ceiling fans were also installed. The new classrooms now have far less fixtures, while providing greater functional flexibility. To monitor the amount of energy being used in classroom #227 of Guggenheim Hall, a voltameter was installed. A solar assisted exhaust fan located in a chimney vent provides a small amount of additional ventilation from a natural source. The classrooms were painted with low VOC paint, contributing to healthy air quality both during and after the construction process. The students chose a light yellow-white shade which is shown to increase comfort and clarity for the eyes, while increasing the effect of daylight in the classrooms. Translucent rolling shades were installed to allow for exterior views while minimizing sunlight infiltration, heat gain and glare. 12 The wood trim around the windows and doors was reused and faux painted to mimic historic wood tones. Soundboards were installed to increase acoustical performance while serving as announcement and display boards for students. The substrate of the soundboards consisted of recycled fiberglass and the fabric contained 100% recycled polyester fibers, derived from plastic bottles. The carpet installed in the classrooms also contained 100% recycled content backing and 75% recycled fibers. All existing carpet was reclaimed and shipped to the Interface Flooring Company, a company which routinely re-manufactures reclaimed carpet into new carpet backing. The construction waste throughout the process was sorted and recycled. Diagram 1: First Floor Plan Diagram 2: Second Floor Plan CSU Facilities Management coordinated the demolition and the construction phases of the classroom remodel. The project scope included three medium-sized lecture classrooms, and the men’s and women’s restrooms. The classrooms were re-opened for classes in August, 2002. The largest of the three classrooms accommodates 70 students, while the other two each hold 30. Framed displays illustrate the design process and materials and methods for the classroom design to enable all faculty, students, and visitors to learn from these documented experiences. 13 The Guggenheim Green Classroom project was also presented with the unique opportunity to participate in the pilot program for LEED – CI. The Guggenheim classrooms were one of the first efforts towards CSU becoming a leader in environmental education and research. Not only are the classrooms designed to be a showcase for sustainable design on the campus of CSU, numerous opportunities to communicate the green tenant finish process has also occurred. The remodel of the Guggenheim classrooms proved to be a great opportunity for students and the department to become involved in the design and construction process. The collaboration process allowed students to look at the elements of teaching and learning classroom, listen to new ideas, be exposed to the phases of a university construction project, and above all, to learn to apply the concepts of sustainable building in an existing setting. The Green Classrooms at Guggenheim Hall have been recognized on and off-campus for the innovative process and results. Purpose The purpose of this case study was to assess the quality of a classroom remodel in a higher education institution. Both the teaching and learning environments as well as the level of green design integration were assessed. Glossary of Terms All of the following terms are from LEED, which has compiled the most accurate and up-to-date definitions on the current technologies. 14 Green design – a process to design the built environment while considering environmental responsiveness, resource efficiency, and cultural and community sensitivity. Whole Systems Thinking – a process that includes all members of the design team including building owners, architects, engineers, manufacturers, contactors, maintenance staff, and building occupants. Volatile Organic Compound – (VOC) any carbon compounds that participate in atmospheric photochemical reactions. Thermal Comfort – a condition of mind experienced by building occupants expressing satisfaction with the thermal environment. Daylighting – the controlled admission of natural light into a space through glazing with the intent of reducing or eliminating electric lighting. By using solar light, daylighting creates a stimulating and productive environment for building occupants. Reuse – a strategy to return a material to active use in the same or a related capacity. Reduce – a strategy to use less of a material or to use it more efficiently. Recycle – a strategy to process material to extend the usable life of the material. (LEED, 2000) Methodology The methodology for this qualitative study involves the data collection (five steps), the identification of the participants in this study, the data analysis, and the identification of limitations. It is important to note that the data collection took place over a series of several semesters over the course of three years. The data collection consisted of two phases (pre- and post-design) and five steps: 15 Pre-Design – Step 1 The first step of the data collection process consisted of an assessment of a pre-design survey to evaluate the perceptions of the students (the end users), regarding the largest of the three Guggenheim classrooms, prior to the classroom remodel. This survey was administered prior to the researcher’s involvement in the project. The survey assessed the students’ perceptions of the temperature of the room, noise levels, room layout, acoustical characteristics, furniture and equipment, audio visual equipment, lighting, aesthetics, daylighting, and personal space. The survey was developed by graduate students enrolled in the MC 572 Facilities Planning and Management course. Its goal was to define the characteristics of a teaching and learning environment. The participants in this study were undergraduate construction management and interior design majors enrolled in a course which met in the Guggenheim classrooms. The surveys were analyzed using rudimentary statistical analysis that determined percentages and total numbers. The researcher was given full access to this data to fully report the findings of this existing study. Post-Design – Step 2 The second step of the data collection process consisted of five personal interviews conducted by the researcher. Participants were the initial design team members of the classroom remodel. Questions used in the interviews centered on determining the lessons learned from the design and construction process used in the remodel. The questions assessed the design team’s perceptions of the success of the design process to implement sustainable principles in an existing classroom. The questions also addressed utilized technologies in a remodel, the construction materials and 16 methods, the purchasing procedures, the change process, and then the teams overall satisfaction with the results. Participants in this study were selected because they had participated on the design team. Members of the design team included faculty, facilities management, project management, the engineering field, and one of the graduate students, who agreed to participate in this study. Data collected in step 2 were transcribed and coded for themes that emerged. Post-Design – Step 3 The third step of the data collection process consisted of two personal interviews conducted by the researcher. The participants were the faculty members who had taught both in the ‘old’ classrooms, and who were currently teaching in the remodeled classrooms. Similar to the initial pre-design survey, the interview assessed the quality of the learning environment including the temperature of the room, noise levels, room layout, acoustical characteristics, furniture and equipment, audio visual equipment, lighting, aesthetics, daylighting, and personal space. Participants in this study were selected because they were faculty members who taught in both the ‘old’ and remodeled classrooms and who agreed to participate in this study. As was done is step 2, the data collected in step 3 was transcribed and coded for themes that emerged concerning the perceptions of the professionals involved in the remodel project. 17 Post-Design – Step 4 The fourth step of the data collection process was a post-design survey administered to undergraduate students with construction management and interior design majors to evaluate student perceptions of the Guggenheim classrooms. This survey was identical to the survey instrument administered in step 1, prior to the classroom design. The participants for the post survey were students in MC 151 Construction Materials and Methods and MC 363 Plan Reading for Estimating who were invited to complete the survey. These surveys were administered and collected in the courses and included both construction management and interior design students enrolled in the fall 2005 semester. These are the same courses that were surveyed prior to the classroom remodel to increase the post-design survey’s validity and reliability. The surveys were analyzed using the same method as step one, rudimentary statistical analysis that determined percentages and total numbers. Post-Design – Step 5 The final step of the data collection process was to assess the level of green design achieved in a remodeled classroom using the LEED – CI rating system as an assessment tool. This assessment was conducted by the researcher as part of a team that included three other LEED accredited professionals, and resulted in a completed LEED – CI document listing the design strategies and materials used in the new learning environment. Steps 1 through 4 were sequential and the analysis of step 5 was a lengthy, detailed process and occurred simultaneous to the interviews and the post-design survey. All five steps of the data 18 collection, including surveys and interviews, were distributed after approval from the human subjects committee. The limitations of this case study relate to issues such as 1.) perceptions versus reality and 2.) the fact that a case study can not be generalized to a larger population. Consistent with most research, it is beyond the control of the researcher to assess the authenticity or accuracy of a participant’s thoughts and reflections. Findings The first step of data collection consisted of a pre-design survey to evaluate the student perceptions of the largest of the three Guggenheim classrooms prior to the classroom remodel. In the fall of 2001, the students were administered a survey by graduate students in the MC 572 Facilities Planning and Management course to determine which aspects of the classrooms could be improved. The results provided guidelines to the graduate students who began initial design research for the classroom remodel. Data from the initial pre-design survey were as follows: Table 1: Percentage of responses to the survey in Step 1 QUESTION 1. The temperature of my classrooms are comfortable and do not distract from my learning. 2. Noise from outside the classroom does not interfere with hearing the instructor 3. I prefer classrooms with a lot of color in the décor. 4. I prefer classrooms with neutral colors in the décor. 5. I am able to hear my instructors clearly most of the time. Strongly Agree/ Agree 32% No Opinion 0% Disagree/ Strongly Disagree 58% 66% 0% 34% 31% 50% 19% 40% 78% 47% 4% 13% 18% 19 QUESTION 6. The desks/tables are appropriate for the function and setting of each room 7. The classroom furniture is comfortable and does not distract from my learning. 8. Audio and video presentations are clear. 9. The lighting in my classrooms enhance note taking and viewing of overheads, videos, and films. 10. Structural elements or equipment do not block my line of sight to the instructor or screen. 11. The desk or table tops are clean and the floor is clear of trash. 12. The aesthetics of the classrooms positively affect my desire to go to class. 13. I believe natural light in classrooms improve (or would improve) my motivation to learn and go to class. 14. I associate the onset of headaches or other physical ailments with being in this room for a substantial amount of time. 15. I have enough personal space around me to facilitate taking notes and listening to lectures without distractions. 16. It is convenient for me to recycle and/or throw away my trash while in the classrooms. Strongly Agree/ Agree 25% No Opinion 15% Disagree/ Strongly Disagree 60% 20% 20% 60% 29% 38% 19% 26% 52% 36% 65% 11% 24% 62% 0% 28% 19% 41% 40% 68% 27% 5% 19% 40% 41% 34% 8% 58% 12% 33% 55% With the results from this initial survey, the results would be utilized in the design of the classroom remodel. Again, the overall goal was to create a positive teaching and learning atmosphere while reducing the impact that traditional construction often has on the environment. The graduate students assessed from the surveys that the temperature in the classroom, the classroom furniture, and the audio/visual presentations were all areas that the majority of the students using the classroom felt needed to be improved upon. It was also assessed that other areas of concern involved outside noise and the lighting in the classrooms. Students felt that the classroom décor and aesthetics were not significantly as important to their learning environment. From this information, the design team began to strategize a plan for the classroom remodel. 20 The second step in the data collection process consisted of five interviews of the initial design team members. The goal of this phase of the research was to determine the challenges and lessons learned about the design process of the classroom remodel. The questions assessed the design team’s perceptions of the success of the design process to implement sustainable principles in an existing classroom. The questions also addressed utilized technologies in a remodel, the construction materials and methods, the purchasing procedures, the change process, and then the teams overall satisfaction with the results. A major challenge of the project related to the level of student involvement. The students had four weeks in class to start the design process and research sustainable options. According to design team members, it was a challenge to coordinate all the information in a short amount of time. Two students were selected to continue with the coordination of the project. There was some loss of control during the construction process for the design team once CSU Facilities Management became the project manager because the project manager often had to make quick decisions in the field. Another challenge to the project was tracking and documenting the actions and decisions made throughout the project. Compared to other classrooms on campus, the design team noted that the University system doesn’t easily allow the freedom to purchase alternative products. The team found it difficult to procure materials from companies with which the University did not currently have a contract. Additionally, State rules call for the minimum of three competitive bids on all purchased items and, due to specific criteria used to select products, there were often less than three companies selling the desired sustainable materials and products. The team determined that it was easier to 21 include the purchasing agents up front in the design process, work closely with them, and make them aware of the design intent. The design team attributed the success of the design to setting goals early, which made the decision-making process easier and avoided conflicts within the team. By setting goals, the team came to a consensus on the best materials and resources to use. Having the Talloires Declaration signed aided in convincing people of the rationale for change and to look at alternative materials and systems. Another reason for the success of these classrooms was the support from the Construction Management department. Facilities Management found that the Construction Management department and its students take pride in the classrooms and have taken care of the classrooms. Overall, the design team was very satisfied with the results of the classroom remodel. For the Facilities Management design team member, the classroom remodel went beyond his expectations. He found that most University classrooms across the campus have been designed to look alike for ease of maintenance. The Guggenheim classrooms have helped to break down the barriers to creating case-specific classroom design. The team has also received positive feedback because of the low amount of energy use, increased natural light and ventilation, improved acoustics, and the connection to the exterior. The third step of the data collection process consisted of two personal interviews from faculty members who had taught both in the ‘old’ classrooms, and who were currently teaching in the remodeled classrooms. Faculty members were interviewed to assess how the classrooms 22 functioned as a teaching environment. The major concerns from the initial surveys included temperature, outside noise, desks and tables, audio visual equipment, lighting, aesthetics, and personal space. According to the faculty, the temperature of the classrooms has been improved. The use of solar shades, the installation of the ceiling fans, and the increased ability to open the windows have drastically improved the thermal comfort in the classrooms. However, the faculty and students felt that it is still too hot on some summer and fall days. The noise levels were also drastically improved. The old classrooms had problems with reflection and reverberation, and the faculty members agreed that they sometimes couldn’t clearly hear themselves speak. Whispering students were often a distraction in the old classrooms, as the sound would echo throughout the classroom. Due to the reorientation of the room and the installation of fabric covered soundboards, the acoustical environment has been significantly improved for both the presenter and the students. The re-orientation of the room also helped the faculty members to connect more with the students. It allowed for more visual contact with the students. There is an area in one of the classrooms towards the north end where students still have some difficulty seeing the projection screen. The faculty felt that the equipment in the classrooms has significantly improved. The former classrooms did not have any permanent equipment; and projectors and television screens had to be rolled into the classrooms. New built-in technology in the front console and the ceilingmounted projector screen has vastly improved the use of technology. Problems occurred with the first ceiling-mounted projector due to the amount of daylight coming into the space. This projector was replaced with one that had more brightness capability to counteract the daylight. 23 Depending on the amount of light coming into the classrooms, and the time of the year, it stillmay be hard to see all of the details on the screen. Despite the conflicts with the projectors, however, the new daylighting conditions are a vast improvement over the old classrooms. The previous classrooms had mini blinds that were almost always closed, which cut the quantity of natural light and prevented a connection to the outside. With the new solar shades, views to the exterior and the connection to the central campus were re-established. The faculty remarked that they would like to have solar shades with slightly less transparency and have the ability to darken the room more in the winter months. Overall, the faculty agrees that the new lighting layouts and flexibility for different light levels are a great improvement. The faculty joke that the classrooms went from orange to green, as the classrooms transformed from a 70s inspired classroom to one that meets the functional needs of current faculty and students, while re-establishing the historic aesthetics appropriate for a 1920s building. The faculty members all agree that the students designing the classroom were mindful of integrating features of an old building with elements of a modern classroom. By adding antique replica ceiling fans and using the original chalkboards rather than the ubiquitous dry erase, the design intent met the functional as well as qualitative needs of the users. One faculty member believes that a prominent aesthetic feature of the classrooms is the faux-finished wood trim around the doors and windows. He also values the effort to restore the original design intent of the building. The fourth step of data collection consisted of a post-design survey to evaluate the student perceptions of the largest of the three Guggenheim classrooms after the completion of the remodel. This survey was identical to the survey used in step one. This survey was administered 24 to students from the Construction Management and Interior Design departments who were currently enrolled in the Fall, 2005 semester. Data from the initial pre-design survey were as follows: Table 2: Percentage of responses to the survey in Step 4 QUESTION 1. The temperature of my classrooms are comfortable and do not distract from my learning. 2. Noise from outside the classroom does not interfere with hearing the instructor 3. I prefer classrooms with a lot of color in the décor. 4. I prefer classrooms with neutral colors in the décor. 5. I am able to hear my instructors clearly most of the time. 6. The desks/tables are appropriate for the function and setting of each room 7. The classroom furniture is comfortable and does not distract from my learning. 8. Audio and video presentations are clear. 9. The lighting in my classrooms enhance note taking and viewing of overheads, videos, and films. 10. Structural elements or equipment do not block my line of sight to the instructor or screen. 11. The desk or table tops are clean and the floor is clear of trash. 12. The aesthetics of the classrooms positively affect my desire to go to class. 13. I believe natural light in classrooms improve (or would improve) my motivation to learn and go to class. 14. I associate the onset of headaches or other physical ailments with being in this room for a substantial amount of time. 15. I have enough personal space around me to facilitate taking notes and listening to lectures without distractions. 16. It is convenient for me to recycle and/or throw away my trash while in the classrooms. Strongly Agree/ Agree 55% No Opinion 8% Disagree/ Strongly Disagree 37% 75% 8% 17% 23% 59% 18% 30% 94% 65% 0% 5% 6% 84% 5% 11% 85% 5% 10% 84% 77% 8% 11% 8% 12% 94% 4% 2% 93% 1% 6% 41% 49% 10% 61% 31% 8% 11% 38% 51% 81% 9% 10% 80% 14% 6% 25 With the results from the post survey, the evaluations indicate that the improvements have had a positive affect for the occupants of the spaces. The survey indicates a significant improvement in the acoustics, classroom furniture, light levels, and personal space, which were all major concerns from the initial pre-design survey. The majority of the students still felt that the aesthetics of the classroom were not important to their learning environment. The fifth step of the data collection process was the assessment of the design of the remodeled classrooms with respect to the LEED-CI rating system requirements. The Green Classrooms of Guggenheim Hall were completed in August, 2002 and, prior to the completion of this research, had served the Department of Construction Management for two full school years. Currently, results are being processed to submit the classrooms for LEED Silver certification under the pilot program for LEED for Commercial Interiors. The following information is outlined based on the LEED rating system to include sustainable sites, water efficiency, energy and atmosphere, materials and resources, and indoor environmental quality. Sustainable Sites: The Guggenheim Building is part of the Colorado State University campus, and will continue to house the Department of Construction Management. Because of its central location on campus and proximity to downtown Fort Collins, Guggenheim Hall has access to the majority of the bus lines that run through the city. Bus drop-off stations are located both outside of Guggenheim Hall and on the center of campus. The campus is also working to make improvements to allow for better bicycle access and other alternative modes of transportation. In addition, this campus also charges for onsite parking and has reduced parking fees for carpool parking. These measures encourage the use of alternative transportation methods. 26 Water Efficiency: In an effort to accomplish lower water use in the building, the restrooms used for the classrooms went through retrofits to increase the water efficiency. In both the Men’s and Women’s restrooms, the water closets were replaced with low-flow systems using under 1.1 gallons per flush. The Men’s restroom was also equipped with two waterless urinals. The lavatories in both restrooms were replaced with low-flow fixtures. Overall, these modifications have a daily volume savings of over 2889 gallons and an annual volume decrease of 728,028 gallons a year. The plumbing retrofits have resulted in water use reduction of over 33% when compared to the original fixtures. Energy and Atmosphere: The lighting fixtures were modified to increase the energy efficiency of the classrooms. The classrooms were evaluated by a professional lighting designer who found that the classrooms had twice the amount of light fixtures and lighting capacity needed for the space. The existing lighting fixtures were cleaned, replaced with more efficient lamps, and rotated in the space to meet ambient lighting needs. The savings of power consumption due to the lighting retrofit was reduced by 52.13% from the original lighting design. The classrooms were equipped with programmable timers that turn the lighting off when the classrooms are not in use. The restrooms were equipped with occupancy sensors that turned the lighting fixtures on when the restrooms are in use. The audio visual equipment used in the classrooms are all EnergyStar rated and permanently installed and calibrated to each classroom. The connected equipment has a lighting load of less than .72 watts per square foot, which is significantly less than most rooms can achieve. 27 Material and Resources: The materials and resources being used for the remodel were carefully evaluated to meet the sustainable goals. The University encourages waste recycling. Guggenheim Hall has recycling drop-off boxes for paper, cardboard, glass, plastics, and metals. Each classroom also has a box for newspapers and co-mingled recycling. The classrooms also maintained the majority of the non-shell components of the building. The ceilings, floors, interior partition walls, and doors within the interior walls were reused. Over 71% of the building components were reused. The remodel also employed strategies to reduce construction waste. The project diverted 85% of the construction waste by recycling or reusing the materials. All of the excess light fixtures, ceiling panels, and 158 chairs were sent to the CSU surplus center where they were sold at auction for reuse. The cardboard from all of the new furniture pieces was recycled as well as the old carpet. Mini blinds used in the space were used in other classrooms around campus. Paint buckets were reused by the Facilities Management department. The classrooms also reused the light fixtures, projector screens, and blackboards, all of which added up to a reused material value of 11.45% of the total construction materials cost. The fabric, carpet, and wallboards contain both post-consumer and post-industrial recycled content. Over 10% of the construction material cost contains recycled content. Indoor Environmental Quality: The new carpets installed in the project were all tested by the Carpet and Rug Institute, and have been labeled with the Green Label tag noting that the carpet contains a low VOC number. Another modification to the classrooms was the use of daylighting. The old classrooms had mini blinds on the windows that were almost always pulled closed. The previous audio visual equipment in the classrooms required the room to be almost completely 28 dark. The audio visual equipment was replaced with new devices that allowed for daylighting opportunities. The mini blinds were replaced with solar shades with a transparency level that allows for a constant connection to the exterior. Discussion and Conclusion The purpose of this case study was to assess the quality of an existing classroom remodel in a higher education institution. The five steps of data collection were utilized to assess the end users perceptions of the Guggenheim classroom remodel. To assess the students perceptions of the remodeled classrooms, evaluation of the two surveys, pre and post-design, were compared. The perceptions of the faculty verified the enhancements to the classrooms that the students had noted. The results from the pre-design survey of students and faculty using the Guggenheim classrooms offered insight into the need to provide a functional and healthy teaching and learning environment. From the survey it was determined that some areas of the classrooms needed to be addressed to improve the learning environment for the students. Temperature, outside noise, the classroom furniture, the audio visual equipment, the lighting, the aesthetics, personal space, and the ability to recycle, were all areas where students had concerns with the existing classrooms. Equipped with this information each element of design proposed for the classroom remodel was evaluated based on aesthetics, sustainability, cost, functionality, and availability. For these elements to meet sustainability requirements, the products were evaluated by a class of construction management graduate students, based on recycled content or if the product was 29 recyclable, durable, natural, contained a low amount of VOC, was energy efficient, and/or regionally manufactured. The results between the pre- and post-classroom remodel surveys show the success of the classroom remodel. The temperature of the classroom was improved to the point where students no longer note temperature as a distraction to their learning. However, temperature is still one area that needs to be addressed to increase the comfort of the occupants. The students also felt that noise is now less of a distraction. Although improved, external noise was still a concern for a percentage of students. Guggenheim Hall is located next to train tracks and a busy street which students agree can contribute to acoustical distractions. When students were asked about their ability to hear the instructors, the responses improved significantly. The improved acoustics can be attributed to classroom orientation and installation of the soundboards. With both surveys, many students had no opinion about the aesthetics or design of the classroom. As expressed in the survey, another major improvement was the classroom furniture. Overall, the surveys showed an overwhelming positive support for the classroom design and remodel. It is evident students are proud of the classroom and are taking care of it. They contribute to keeping it clean and clear of trash. Another major concern expressed in the initial survey of the classrooms was the lack of personal space. After the remodel, students felt that they have more personal space, enjoy the larger tablet arm desks, and appreciate the comfort of upholstery and padding on the seating. The classroom occupancy of the largest room was reduced from 80 students to 70 students, which increased the amount of personal space. Some faculty members would prefer to see these numbers drop to 30 closer to 65 student seats. The faculty also has a large amount of personal space in the front of the classrooms to allow for lectures and presentations. The students agreed that the new desks and tables were more appropriate for the classroom setting, that the furniture no longer distracts from their learning, and that they now have more personal space. Students who responded to the first survey stated that they had less personal space in the old classrooms. The presenter’s moveable cart replaced with a large teaching table that better fits the room. Overall, both students and faculty have more personal space than the old classrooms, which helped lead to the positive survey and interview responses. In analyzing the data, it is clear that the current audio visual presentations are superior to the old classrooms. The students in the old classrooms were split when deciding if the lighting was appropriate for note taking and viewing. The majority of the students in the new classroom found that the light was appropriate for the tasks they were completing. With the reorientation of one of the classrooms, the main entrance to the classroom was rotated from being at the front of the classroom to being on the side. This new orientation reduced the amount of distraction when a student would enter late or leave early. The analysis using the LEED Rating system verifies that the design and construction processes were comprehensive and confirms that the project classroom remodel can be correctly referred to as a green classroom. The assessment of the remodeled classrooms against the LEED – CI rating system clearly verified that the strategies used by the design team were aligned with green design goals and principles. 31 As universities decide to remodel existing classrooms, there are several key factors that will aid in the success of the classroom design. It is imperative to get student support and input when designing the classrooms. The students who are the occupants of the space are in a position to offer appropriate suggestions for improving and remodeling the classrooms. As can be observed from the Guggenheim case study, student involvement in a classroom remodel offers excellent opportunities for a service and learning project. Also, by involving the faculty who use the classrooms, additional ideas and support can be provided. One of the most important factors when completing a classroom remodel is to have well-defined goals early on in the design process to act as a framework for the decision making process. The Guggenheim team found that creating such a framework resulted in making appropriate, sustainable selections when designing the classrooms. When going through the design process, it is also imperative to get all members of the team and representatives from the various stakeholders involved up front to examine the issues, set common goals and explore opportunities for the project. The sustainable classroom remodel for Colorado State University was a criteria first step in the pursuit of an environmentally-conscious university setting and as a tenet of the Tallories Declaration. The Green Classrooms of Guggenheim Hall were intended to be a showcase for sustainable principles and a place to teach the students, faculty, and community members about the benefits of green design. The Guggenheim project was successful in improving the teaching and learning environment. In the process, thanks to a concerted effort by an integrated team, the project results now teach others how to provide sustainable sites, increase water efficiency, 32 improve overall energy performance, use sustainable materials and resources, decrease construction waste, create a healthy indoor environment, and how to create an optimal teaching and learning environment. With an understanding of the specific issues experienced with the Guggenheim Hall classroom remodel, the lessons learned can be carried on to other classroom designs and remodels across the country. 33 References Babey, E. (March 26, 1991). The Classroom: Physical Environments that Enhance Teaching and Learning, U.S. California. Blueprint for a Green Campus, The Campus Earth Summit Initiatives for Higher education, Extracted from envirocitizen website, Blueprint for a Green Campus pp 1-2). www.envirocitizen.org Coleman, Cindy (2002). Interior Design, Handbook of Professional Practice. New York: McGraw Hill Cunningham, Cody (2002, Aug. 1). Buildings That Teach. American School and University. www.asumag.com/ar/University_buildings_teach Graetz, K. A. and Goliber, M.J., Designing Collaborative Learning Places: Psychological Foundations and New Frontiers, The Importance of Physical Space in Creating Supportive Learning Environments, New Directions for Teaching and Learning, Winter, 2002, 92. Greening the Campus: Sustainability and Higher Education, http://www.islandpress.org/ecocompass/general/detail.html, retrieved June 20, 2004. High Performance School Buildings, Resource and Strategy Guide, Sustainable Buildings Industry Council, 1999. Niemeyer, D. (2003). Hard Facts on Smart Classroom Design: Ideas, Guidelines, and Layouts. The Scarecorw Press, Inc. Lanham, Maryland. Orr, David. (1994). Earth in Mind: On Education, Environment, and the Human Prospect. Washington, D.C.: Island Press. Smarter College Classrooms: http://www.classrooms.com, retrieved September 22, 2003. 34 U.S. Green Building Council http://www.usgbc.org, Oct 10, 2003 U.S. Green Building Council. (2001). Leadership in energy and environmental design (LEED) Online. http://www.usgbc.org ULSF, What is the Talloires Declaration? Association of University Leaders for a Sustainable Future www.ulsf.org/programs_talloires.html 35 Appendices LEED for Commecial Interiors Guidelines and Credits The following information is the entire scorecard for the LEED for Commercial Interiors. Not all of these credits applied to the green classrooms in Guggenheim Hall. Sustainable Sites 7 points possible Credit 1 Site Selection 1-3 Credit 2 Development Density 1 Credit 4.1 Alternative Transportation, Public Transportation Access 1 Credit 4.2 Alternative Transportation 1 Credit 4.4 Alternative Transportation, Parking Availability 1 Water Efficiency 2 points possible Credit 3.1 Water Use Reduction 20% reduction 1 Credit 3.2 Water Use Reduction 30% reduction 1 Energy and Atmosphere 14 points possible PreReq 1 Fundamental Building Systems Commissioning req. PreReq. 2 Minimum Energy Performance req. PreReq. 3 CFC Reduction in HVAC&R Equipment req. Credit 1.1 Optimize Energy Performance, Lighting Power 1-3 Credit 1.2 Optimize Energy Performance, Lighting Controls 1-2 Credit 1.3 Optimize Energy Performance, HVAC 1-2 Credit 1.4 Optimize Energy Performance, Equipment & Appliances 1-3 Credit 3 Additional Commissioning 1 Credit 5.1 Measurement and Verification, Sub-Metering 1 Credit 5.2 Measurement and Verification, Energy Costs Paid 1 Credit 6 Green Power 1 Materials and Resources 14 points possible PreReq 1 Storage & Collection of Recyclables req. Credit 1.1 Building Reuse, Long Term Lease 1 Credit 1.2 Building Reuse, Maintain 50% of Non-Shell Systems 1 Credit 1.3 Building Reuse, Maintain 75% of Non-Shell 1 Credit 2.1 Construction Waste Management, Divert 50% 1 Credit 2.2 Construction Waste Management, Divert 75% 1 Credit 3.1 Resource Reuse, Reuse 5% 1 Credit 3.2 Resource Reuse, Reuse 10% 1 Credit 3.3 Resource Reuse, Reuse 30% 1 Credit 4.1 Recycled Content, Use 5% Post-Consumer/10% total 1 Credit 4.2 Recycled Content, Use 10% Post-Consumer/20% total 1 Credit 5.1 Regional Materials, Use 20% manufactured regionally 1 Credit 5.2 Regional Materials, Use 10% extracted regionally 1 Credit 6 Rapidly Renewable Materials 1 Credit 7 Certified Wood 1 Indoor Environmental Quality 15 points possible PreReq 1 Minimum IAQ Performance req. 36 PreReq 2 Environmental Tobacco Smoke (ETS) Control req. Credit 1 Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Monitoring 1 Credit 2 Ventilation Efficiency 1 Credit 3.1 Construction IAQ Management Plan, During Construction 1 Credit 3.2 Construction IAQ Management Plan, Before Occupancy 1 Credit 4.1 Low-Emitting Materials, Adhesives and Sealants 1 Credit 4.2 Low-Emitting Materials, Paints 1 Credit 4.3 Low-Emitting Materials, Carpet 1 Credit 4.4 Low-Emitting Materials, Composite Wood 1 Credit 4.5 Low-Emitting Materials, Furniture and Furnishings 1 Credit 5 Indoor Chemical and Pollutant Source Control 1 Credit 6 Controllability of Systems 1 Credit 7.1 Thermal Comfort 1 Credit 7.2 Thermal Comfort, Permanent Monitoring Systems 1 Credit 8.1 Daylight and Views, Daylight 75% of Spaces Credit 8.2 Daylight and Views, Views for 90% of Spaces 1 Innovation and Accredited Professional 5 Additional Points Credit 1.1 LEED CI Innovation Credits 1 Credit 1.2 LEED CI Innovation Credits 1 Credit 1.3 LEED CI Innovation Credits 1 Credit 1.4 LEED CI Innovation Credits 1 Credit 2 LEED Accredited LEED Professional 1 57 Total Points Available LEED Certified for Commercial Interiors 21 to 26 credits LEED Certified Silver for Commercial Interiors 27 to 31 credits LEED Certified Gold for Commercial Interiors 32 to 41 credits LEED Certified Platinum for Commercial Interiors 42 of more credits 37 The Talloires Declaration The Talloires Declaration: University Presidents for a Sustainable Future We, the presidents, rectors, and vice chancellors of universities from all regions of the world are deeply concerned about the unprecedented scale and speed of environmental pollution and degradation, and the depletion of natural resources. Local, regional, and global air pollution; accumulation and distribution of toxic wastes; destruction and depletion of forests, soil, and water; depletion of the ozone layer and emission of "green house" gases threaten the survival of humans and thousands of other living species, the integrity of the earth and its biodiversity, the security of nations, and the heritage of future generations. These environmental changes are caused by inequitable and unsustainable production and consumption patterns that aggravate poverty in many regions of the world. We believe that urgent actions are needed to address these fundamental problems and reverse the trends. Stabilization of human population, adoption of environmentally sound industrial and agricultural technologies, reforestation, and ecological restoration are crucial elements in creating an equitable and sustainable future for all humankind in harmony with nature. Universities have a major role in the education, research, policy formation, and information exchange necessary to make these goals possible. The university heads must provide the leadership and support to mobilize internal and external resources so that their institutions respond to this urgent challenge. We, therefore, agree to take the following actions: 1. Use every opportunity to raise public, government, industry, foundation, and university awareness by publicly addressing the urgent need to move toward an environmentally sustainable future. 2. Encourage all universities to engage in education, research, policy formation, and information exchange on population, environment, and development to move toward a sustainable future. 3. Establish programs to produce expertise in environmental management, sustainable economic development, population, and related fields to ensure that all university graduates are environmentally literate and responsible citizens. 4. Create programs to develop the capability of university faculty to teach environmental literacy to all undergraduate, graduate, and professional school students. 5. Set an example of environmental responsibility by establishing programs of resource conservation, recycling, and waste reduction at the universities. 6. Encourage the involvement of government (at all levels), foundations, and industry in supporting university research, education, policy formation, and information exchange in environmentally sustainable development. Expand work with nongovernmental organizations to assist in finding solutions to environmental problems. 38 7. Convene school deans and environmental practitioners to develop research, policy, information exchange programs, and curricula for an environmentally sustainable future. 8. Establish partnerships with primary and secondary schools to help develop the capability of their faculty to teach about population, environment, and sustainable development issues. 9. Work with the UN Conference on Environmental and Development, the UN Environment Programme, and other national and international organizations to promote a worldwide university effort toward a sustainable future. 10. Establish a steering committee and a secretariat to continue this momentum and inform and support each other's efforts in carrying out this declaration. [Jean Mayer, President and Conference convener Tufts University, U.S.A. | L. Avo Banjo, Vice Chancellor University of Ibadan, Nigeria | Robert W. Charlton, Vice Chancellor and Principal University of Witwatersrand, Union of South Africa | Michele Gendreau-Massaloux, Rector l'Academie de Paris, France | Augusto Frederico Muller, President Fundacao Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso, Brazil | Calvin H. Pimpton, President and Emeritus American University of Beirut, Lebanon | T. Navaneeth Rao, Vice Chancellor Osmania University, India | Stewart Saunders, Vice Chancellor and Principal University of Cape Town, Union of South Africa | David Ward, Vice Chancellor Canipinas, U.S.A. | Pablo Arce, Vice Chancellor Universidad Autonoma de Centro America, Costa Rica | Boonrod Binson, Chancellor Chuialongkorn University, Thailand | Constance W. Curris President University of Northern Iowa, U.S.A. | Adamu, Nayaya Mohammed Vice Chancellor Ahmadu Bello University, Nigeria | Mario Ojeda Gomez President Colegio de Mexico, Mexico | Wesley Posvar, President University of Pittsburgh, U.S.A. | Pavel D. Sarkisow, Rector D. I. Mendeleev Institute of Chemical Technology U.S.S.R. | Akilagpa Sawyerr, Vice Chancellor University of Ghana, Ghana | Carlos Vogt, President Universidade Estadual de Brazil | Xide Xie, President Emeritus Fudan University, People's Republic of China] 39