On the Trail of Dr Hocken, Book Collector

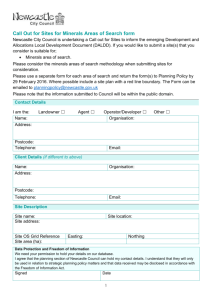

advertisement

On the Trail of Dr Hocken, Book Collector Donald Kerr 2010 Fellow July 2010 1 Contents Title 1 Contents 2 Introduction 3 Prime Objective of Research Trip 4 Research Itinerary 4 The Trail Begins… 5 Cambridge-Stamford-Lincoln-Grimsby-Woodhouse Grove School-Newcastle-Edinburgh-Dublin-Bristol-Oxford-London The Trail Documented 19 Omissions 20 Research Caveat 21 Prime Benefits of Research 22 By-products of Research 25 Conclusion 28 Acknowledgements 29 Appendix I: Pictures 30 References 34 2 Introduction Dr Hocken is one of the Trinity of New Zealand’s early book collectors, alongside Sir George Grey and Alexander H. Turnbull. The latter two have books written about their collecting activities (Kerr; McCormick). Hocken does not. He deserves one. Dr Hocken’s contribution to New Zealand’s heritage and culture is primarily through his collecting interests: Captain James Cook and Australasian and Pacific voyages and travel; Samuel Marsden and early missionaries in New Zealand; Edward Gibbon Wakefield and the New Zealand Company; the early history and settlement of New Zealand, including Maori; and the early development of the Otago Region. He promoted his collection by producing a number of historical books, and importantly, compiling one of the first bibliographies on literature relating to New Zealand. Dr Hocken was born in Stamford, Lincolnshire, in 1836. He was schooled at Woodhouse Grove School, Apperely Bridge, Yorkshire, and later attended Newcastle-UponTyne Practical School of Science as an apothecary and surgeon’s assistant. He then attended the ‘Original’ (Ledwich) School of Medicine, Dublin, where he qualified as a surgeon. Prior to his arrival in New Zealand in February 1862, he worked as a ship’s surgeon on, in particular, Isambard K. Brunel’s SS Great Britain, which is now housed at Bristol. Hocken made two trips back to his homeland, in 1882 and 1901-04. He died in May 1910, aged 74. Dr Hocken was a member of a number of prestigious British institutions such as the Linnean Society (London), the Japan Society, and the Royal Anthropological Society. As a collector based in Dunedin, he was strongly reliant on letter writing as a means of obtaining materials for and about his collection. As a consequence, he corresponded with a number of individuals based in Great Britain including (among others) Charles Darwin, James EdgePartington, Andrew Lang, Bishop Samuel Edward Marsden, Frederick George Moore, Sir 3 Richard Nicholson, Richard Garnett, Edward A. Petherick, W. S. Silver, H. G. Robley, and Sir Frederick Young. Dr Hocken’s early family life and education was firmly based around Methodist teachings. His father, the Rev. Joshua Hocken, was an itinerant Methodist preacher who undertook circuit duties in towns such as Stamford, Grimsby, and Norwich. They were formative years for Dr Hocken. 1. Prime Objective of Research Trip To visit those locations pertinent to Dr Hocken’s life before he arrived in Dunedin in 1862, and examine primary documents (manuscripts and books) in institutions and libraries that relate to his early life and his collecting activities. Institutions range from the British Library, the Linnean Society (London), the Japan Society Library, and University of Newcastle, to Cambridge University Libraries, Mercer Court Library, Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland, Dublin, the Grimsby Public Library, and the SS Great Britain Archives, Bristol. Individuals to whom he met and corresponded are listed above. Archives of materials related to these men are extant in some of the above institutions. They required accessing. 2. Research Itinerary Dunedin to London London to Cambridge (Cambridge University Libraries) Cambridge to Stamford/Lincoln/Grimsby (birthplace; Methodist circuit; early residence) Grimsby to Leeds (accommodation base) to Apperley Bridge (Woodhouse Grove School), nr Bradford Leeds to Newcastle upon Tyne (Newcastle Libraries; Newcastle Practical School of Science) Newcastle to Edinburgh (University – Garnett & Lang materials) Edinburgh to Bristol Bristol to Dublin (‘Original’ Medical School; College of Surgeons)) Dublin to Bristol (SS Great Britain) Bristol to Oxford (Garnett & Lang materials) Oxford to London (British Library, Japan Society, Linnean Society (London), etc) London to Dunedin 4 The duration of the trip was 35 days, which included ‘down-time’ on weekends, travel time, and any unforeseen delays, e.g Bank Holidays. 3. The Trail Begins… 1. Cambridge University Library One of Hocken’s collecting strengths was materials on or about Edward Gibbon Wakefield, the New Zealand Company, and its association with the early history and settlement of New Zealand. One person whom Hocken corresponded with was Sir Frederick Young (18171913), long-time member of the Royal Colonial Institute and advocate of the permanent union of the colonies. Sir Frederick had also known Wakefield, and he was the prime mover in England advocating a memorial for Wakefield. He was a key person for Hocken in facilitating further introductions to Wakefield associates such as Mrs Amy Storr, sister of Albert Allom, and Mrs Ford, the sister of Sir William Molesworth.1 Although the Young Archive in the Royal Commonwealth Manuscript Collection revealed nothing on Hocken (no in-coming letters or name mention), the process highlights the absolute necessity for every researcher to ‘walk’ every path, even though at times it ends up a cul-de-sac with no results. Unfortunately, cul de sacs also occurred with the Archives of Richard Garnett and Andrew Lang in the Cambridge University Library Manuscripts Department. Dr Garnett, Keeper of Printed Books at the British Museum, met and corresponded with Hocken about Wakefield, and Lang was particularly interested in Dr Hocken’s own account of the Fire-walking ceremony that he had observed while visiting Fiji in April 1898. Curiosity and serendipity are those magical components of research. While waiting for my interview to gain access to the Cambridge University Library Collections, I talked to a ‘…I am one of the living witnesses to the fact that, if it had not been for Wakefield, New Zealand would have now been, instead of a Dominion of Great Britain, a appendage of France. My personal acquaintance with Wakefield commenced in the year ‘1839’ – the very year in which the foundations of the Colony were laid by him, and with all the details of which I was entirely and personally acquainted.’ An enclosure to a letter by Sir Frederick Young to Joseph Ward, 8 May 1908. MS-0451025/014. Hocken Library. 1 5 researcher next in line who was working on 18th century garden history, with special reference to diaries and journals written by Sir Joseph Banks. This enabled me to mention (and promote) the Special Collections, University of Otago’s strength in garden history (through Esmond de Beer’s collecting of John Evelyn) and Dr Hocken’s own botanical interests. 2. Stamford Hocken was born in Stamford, Lincolnshire, on 14 January 1836. Church towers and spires dominate the townscape, and with its many old buildings the town is often used as a backdrop for television series and movies, eg. Pride and Prejudice, and the Da Vinci Code. Prior to my research trip to England, it was believed that the Rev. Joshua Hocken was just passing through Stamford as part of his Methodist circuit duties when his third son (Thomas Morland) was born. This is not true, as verified by the documents in Lincolnshire Archives. The family were actually resident in Stamford, it being the Rev. Hocken’s third year of his station there. It was important to visit this wonderfully picturesque market town, and ground the family presence in historical fact (see Appendix i). 3. Lincoln a. Lincolnshire Archives Lincolnshire Archives contains most of the Methodist Archives for the county of Lincoln. Extant Methodist Circuit Account Records helped establish the Hocken family’s whereabouts in Stamford and Grimsby and revealed the minutiae that helped the family run their household. The three books gave Quarterage costs for the parents and children, the cost of washing and servants, toll gate and letter fees, the cost of candles, coal and class books, and medicines; verified the circuit schedules that the Rev. Joshua Hocken undertook; and gave Methodist member numbers in the area. Although a small detail, one book (Meth 6 B/Stamford/13/1) gave the cost of Mrs Hocken’s confinement when young Hocken was born: the princely sum of £2. Hocken’s father was obviously highly regarded in Grimsby. He was ‘unanimously invited’ to stay on in this third year and be superintendent of the circuit. In addition, the Archives had baptism entries from the Public Record Office on microfilm, Church of England records of Stamford Churches on microfiche, and index cards to the Stamford Mercury, the newspaper of the day. Because Hocken was baptized on 25 February 1837, well over a year after his birth, it was suggested that he may have been baptized in an Anglican Church service prior to the Methodist one. Unfortunately, patient trawling revealed no entries to a prior baptism. Wednesday was genealogy day and the Archives were full of researchers. By necessity I had booked ahead for a reader table, proving again that planning one’s research schedule is vital. b. Lincoln Public Library Before the Archives opened, I visited the Lincoln Public Library. They had a copy of the Rev. Joshua Hocken’s Brief History of Wesleyan Methodism (1839), his first book and unacknowledged in any previous work on Dr Hocken. It is an extremely scarce work and I was able to get a copy, which included the engraved frontispiece titled ‘Grimsby Wesleyan Methodistic Tree’. The Library also had copies of George Lester’s Grimsby Methodism (1743-1889) and the Wesleys in Lincolnshire (1890), a work not available in New Zealand. Importantly, Lester acknowledged a ‘large indebtedness’ to Rev Joshua Hocken’s pamphlet and gave details on whom Hocken shared circuit duties with, as well as details on circuit life. One brief example contextualises the arduous work Hocken’s father faced, albeit dated a little earlier. It ‘was then six hundred miles round, and required twelve weeks travelling. Sometimes a mob followed me with volleys of oaths and curses for a mile together…’.2 Robert Costerdine, stationed in Lincolnshire in 1764, described his first circuit. Cited in George Lester’s Grimsby Methodism (1743-1889) and the Wesleys in Lincolnshire (London: Wesleyan-Methodist Book-Room, 1890), p.55. 2 7 4. Grimsby, Lincolnshire Before arriving in Grimsby, I managed to pass through nearby Laceby and take photographs of the Laceby Methodist Chapel. The foundation stone of this particular chapel was laid by the Rev. Joshua Hocken on 21 February 1837, and the text his sermon was based on was, rather appropriately, Matthew XVI. 18: ‘And I say also unto thee, That thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church: and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.’3 Joshua was present when the Chapel was finally opened on 15 June 1837. Using the Grimsby Public Library microfilm of the Stamford Mercury I trawled through issues dated around Hocken’s birth; an opportunity to contextualise that event with other local and national happenings. The Skelton Bills and Poster Collection on microfilm also proved an invaluable resource. From the hundreds of ephemeral single sheet posters and notices I was able to source Sermons, Love Feasts, and Quarterly Fund Collections led by the Rev Joshua Hocken, and the schedules he faced on circuits over the years 1836 to 1839. Again, both formats were particularly good at grounding the Rev Hocken’s activities as well as confirming where the family resided. A brief example will suffice. From May to July 1837, Joshua walked from Grimsby to Caistor, Cleethorpes, Waltham, Limber, Keelby, and Laceby, while between May and October 1838, he faced a more extensive circuit walking from Grimsby to Caistor, Cleethorpes, Laceby, Humberstone, Thoresby, Holton, Waltham, Hatcliffe, Scartho, Ashby, Keelby, and Limber. It is unlikely that Hocken’s father was present at his first Christmas Day celebration because Joshua had to be at Limber for a 10 o’clock sermon (a walk of 10 miles west from Grimsby), back to Laceby (4 miles from Grimsby) for a 2 o’clock sacrament service’s schedule, and then north to Stallingborough (six miles from Grimsby) for another sacrament service at 6 o’clock. Indeed, even on the day of young Hocken’s baptism, Joshua was scheduled to be at Keelby at 9.30 am, and then to Caistor for 2 and 6 o’clock services. If 3 The Holy Bible, Oxford Edition, p. 621. 8 present at all, he would have had to be on the road very early, and incredibly organized. All these activities (and more) were verified by the posters and notices and helped contextualize the early life, religious background and education of Thomas Morland Hocken. A small cache of books was also accessed through the Grimsby Public Library Local History section. These included William Leary’s Ministers and circuits in the Primitive Methodist (1990) and Forward with the Past: the Grimsby Circuit (1996), to Rod Ambler’s Ranters, Revivalists & Reformers (1989). As secondary sources that helped contextualize a Methodist minister’s life (and his family) they were invaluable. Identification of the location of the Wesleyan Chapel (where Hocken was baptized) on New Street was made possible through old photographs; a boot scraper representing the last tangible remains of the building. 5. Woodhouse Grove School, Yorkshire By 1844, Joshua and his wife Anne had moved to Norwich. The family was three less. Thomas Morland and his two older brothers, James and Joshua, were attending Woodhouse Grove, a boarding school for the sons of Methodist preachers at Apperley Bridge (four miles across the fields and open moorland from Bradford; eight miles from Leeds) and which had been established as a balance to Kingswood School, an enterprise established in the south by John Wesley. In 1833, the school Chapel was built, and the opening featured the Rev. Jabez Bunting, a founding Trustee and mentor to the Rev. Joshua Hocken.4 Young Hocken was at the ‘Grove’ from 1844 to 1850. I was toured around the school by Hugh Knowles, the school historian, who informed me on what parts of the school existed when Hocken was there: the tower, the school Chapel, portions of buildings, examples of old boarding rooms, and the River Aire (where Hocken swam; see Appendix ii). There was also 4 One famous master, albeit for a short period, was the Rev. Patrick Brontë, who met there his future wife Maria Branwell Fennell, the mother of the Brontë sisters. On making a decision on taking Holy Orders, Brontë resigned. His daughter Emily captured the opening of the Chapel for all times in her Wuthering Heights (1847). There she portrays the pandemonium of the event and the pompous Jabes Branderham (Jabez Bunting) and his ‘Seventy Times Seven’ text. Cited in Emily Brontë, Wuthering Heights (New York: Nelson Doubleday, [1975]), pp. 18-21. See John Lock and Canon W. T. Dixon, A Man of Sorrow. The Life and Times of the Rev. Patrick Brontë 1777-1861 (London: Nelson, 1965). 9 the Coronation Clock, which he donated £5 towards the Coronation Clock Fund when he visited in 1902 (see Appendix iii). It was an invaluable experience. Morning tea was a delightful experience in the staffroom overlooking splendid green grounds. This was a far cry from food descriptions offered in the past by old Grovians (and experienced by Hocken), where the rice was ‘either boiled very dry and then anointed with a thin unguent composed of treacle and warm water, or else baked in huge black tins, in which it looked as if it had been trodden under foot of men. Breakfast consisted of a thick slice of dry bread and about half a pint of skimmed milk, occasionally sour, and sometimes slightly warmed in winter. Supper was an exact repetition of breakfast. Butter, tea and coffee we never saw.’ Occasionally plum pudding, boiled beef, and apple pie were served, and on one day, 5 November, ‘tea and parkin’ was allowed.5 Although curriculum details are extant in secondary sources, nothing pertinent to Hocken’s time as a student has been found.6 The current Headmaster sees the School Archives as important component in the history of the school, and to that end has recently hired an archivist to organise all the files. I met Julian Bolt, the archivist, and am in contact with him in the hope that documents such as school reports, examination questions and other paraphernalia surrounding Hocken’s time at the ‘Grove’ will be discovered. 6. Newcastle a. Newcastle Public Library In 1853, Hocken was apprenticed to Dr Septimus William Rayne, surgeon to the Police Force and to Trinity House of Newcastle, and tutor in operative surgery at Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Hocken lived in Newcastle for six years, and stayed with Rayne at 18 and 19 Blackett Street, 5 Joseph L. Strachan, cited in H. W. Starkey, A Short History of Woodhouse Grove School 1812-1912 (1912), p.29; See also J. T. Slugg, Woodhouse Grove School: Memorials and Reminiscences (London: Published for the Author, T. Woolmer, 1885), p. 161. 6 Joseph Strachan, cited in Slugg, p. 138. An excellent overview of ‘the Division of Time and Labour’ at Woodhouse Grove c.1829 is provided in F.C. Pritchard, The Story of Woodhouse Grove School (Bradford, England: Woodhouse Grove School, 1978), p. 73. 10 and then 61 Westgate Street. In 1854, Hocken attended a ‘course of lectures and practical tuition in medical and pre-medical sciences’ at Newcastle-upon-Tyne College of Practical Science. Using the photograph collection at the Newcastle Public Library I was able to access early images of Blackett Street, which was called at the time a ‘domestic paradise’ for doctors, and Westgate Street. Newspapers on microfilm and publications gave me additional information on Rayne, and other instructors such as Sir John Fife, who had helped found the Newcastle School of Medicine, Dr William Dawson, a lecturer on Midwifery at the Newcastle College, Dr George Robinson, and R.B. Sanderson, botany instructor. All these men were known to Hocken. Indeed, they signed testimonials on his character and skills as a medical student. And it was Sanderson who taught Hocken botany; in 1855-56 he won a silver medal award for this subject, as documented in one of the Practical School of Science leaflets I obtained (see Appendix iv).7 b. Robinson Library, University of Newcastle The Robinson Library, University of Newcastle, also held information relating to the Practical School of Science. This included: an Entry and Registration Book for the Practical School of Science (1851-1860), and a Newcastle Medical and Surgery Minute book 1851-73. Unfortunately, despite the tantalizing promises, there was no mention of Hocken. Alas, another cul-de-sac. There was, however, more success with a two-volume collection of papers amassed by Denis Embleton, surgeon at the Practical School of Science.8 Not only were there various engraved images of the school, but documentation on courses offered, lecturers of the day, and printed pamphlets evoking the spirit surrounding the formation of the School. Two were of particular interest: Sir John Fife’s An Inaugural address delivered at the opening of 7 See Denis Embleton, Papers relating to the College of Medicine. University Archives 16/2/1. Robinson Library, University of Newcastle. 8 See Denis Embleton, Papers relative to College of Medicine. University Archives 16/2/1. Robinson Library, University of Newcastle. 11 the Newcastle-Upon-Tyne College of Practical Science, October 1, 1851 (1851) and George Robinson’s treatise on the cholera outbreak in Newcastle, occurring in 1853, the first year of Hocken’s apprenticeship. Embleton’s collection was a treasure trove (see Appendix v). 7. Edinburgh Over a weekend I had the opportunity to visit Special Collections, the University of Edinburgh. Prior to giving an arranged open lecture, I managed to trawl through Andrew Lang materials in the search for in-coming Hocken letters. While an interesting collection of papers, nothing arose from this search. 8. Dublin, Ireland a. Mercer Library, Royal College of Surgeons, Ireland During the winter term of 1858-59, Hocken left Newcastle and enrolled at the Original Theatre of Anatomy and School of Medicine and Surgery in Dublin. Despite a rather controversial and complicated history, the School was recognized by most other reputable British Medical Colleges.9 In 1858, the School was at 24, 25 and 26 Peter Street, and by the end of Hocken’s studentship, it was renamed the Ledwich School of Medicine, in memory of Thomas Hawkesworth Ledwich (1823-1858), the young but well-known anatomist. Hocken passed his examinations in April 1859 and was admitted as a member of the Royal College of Surgeons (MRCS) and a Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries (L.S.A.). Through the Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland I was able to stay at accommodation close to the city. The Mercer Library, part of the Royal College, was but a stones-throw from my accommodation. Through the kind efforts of Mary O’Doherty, Librarian, I was able to access medical directories, the Minutes of the Ledwich School of E.g. Queen’s University of Ireland, King and Queens College of Physicians, London University, College of Physicians of London, College of Surgeons in Dublin, London, and Edinburgh, and the University of Glasgow. 9 12 Medicine, the Kirkpatrick Archive, and various medical registers. While the Ledwich School files covered (annoyingly) a later period, Hocken was found in the Medical Register (1860), with his address given as 61 Westgate Street, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.10 Dug out from old files were a number of ‘Original’ School posters, each advertising courses, fees, and instructors at the time Hocken attended. Kindly copied, these indeed were finds, verifying details on what was covered in courses and particular instructors, who, similar to the Newcastle contingent, supplied Hocken with testimonials on his character and skills as a medical student. The Kirkpatrick Archives did not reveal anything on Hocken. It did however offer information on Hocken’s instructors: Edward Ledwich, and Drs Mason and Wharton. b. National Library of Ireland A reader’s ticket (with photographs) was essential in order to access books and manuscripts at the National Library of Ireland. Accessing numerous books, I was able to verify courses taken, learn more about Hocken’s instructors, and gather more data on the School. Thom’s Directory verified that the following subjects (with instructors) were taught when Hocken was there: Surgery: Mr William Tagert and Dr Porter; Practice of Physic: Dr Cathcart Lees; Anatomy and Physiology: Drs Ledwich and Mason; Descriptive Anatomy: Mr T. H. Ledwich, Mr E. Ledwich, and Mr O’Doherty; Materia Medica: Dr James Wharton; Midwifery: Dr R. S. Ireland and Dr Sawyer; Chemistry: Dr M. Simpson; Forensic Medicine: Dr Robert Travers; Practical Midwifery: Mr Thomas Powell; and Botany: Dr Joseph Williams. Portions of this information were repeated on pamphlets (also obtained) advertising the School. Importantly, timetables for each subject were uncovered, and these gave an excellent idea on the regime of study faced by Hocken and his fellow students.11 Fees were noted, as well as availability of the daily dissection instruction, something that all candidates were encouraged to do. From 10 Hocken is registered thus: Mem. R. Coll. Surg England 1859; Lic Soc. Apoth. London 1859. Cited in Medical Register. 1860 (London, 1860), p. 163. 11 Medical Directory and General Medical Register for Ireland 1859 (London: John Churchill, [1859]), p.245 13 the testimonials written by instructors, Hocken was a diligent student in these courses. Lambert Hepenstal Ormsby’s Medical History of the Meath Hospital and County Dublin Infirmary (1892) was particular important in that it not only highlighted those gentlemen who worked at Meath (Wharton, Stoke, Lees, Ledwich), but also verified Hocken as a ‘Former Pupil of the Meath Hospital’ between 1858 and 1859. He was listed under ‘T. Morland Hocken’; his preferred nomenclature.12 From my research, I found out that Hocken’s first day of study was 1 November 1858. It was gratifying to find an overview of the lecture given to him (and other first day students) in the 2 November issue of Freeman’s Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser, 1858. This morale booster – delivered by Dr Mason because Ledwich had just died – reveals the attitude, spirit and approach towards medicine inculcated at the School, with one notable dictum: ‘the spirit of doing unto others as others should be done unto them.’ It was something that Hocken no doubt was keenly aware of. While I was uncovering material pertinent to Hocken, his early life, education, and book interests, I was conscious of obtaining a wide range of interesting illustrations for the eventual publication of my book on him. Among other candidates, it was pleasing to sight and secure engraved images of the original School on Peter Street.13 Given that it was a whirlwind research trip of only two days, I achieved much in Dublin. 9. Bristol (SS Great Britain Archive) The above-mentioned testimonials from his instructors at Newcastle and Dublin were used by Hocken to obtain a position as ship’s surgeon on two ships: the White Star, which was part of the White Star Shipping Line, and the famed SS Great Britain, which is now placed at Bristol 12 Lambert Hepenstal Ormsby, Medical History of the Meath Hospital and County Dublin Infirmary. 2nd ed. (Dublin: Fannin & Co, 1892), p. 288. 13 Medical Students Guide Containing the Latest Regulations of all the Licensing Medical Corporations of Great Britain and Ireland… (Dublin: Fannin and Co, [1855]), p.160 for image of ‘Original’ School at Peter Street. 14 docks as a tourist attraction. The SS Great Britain was the world’s first ocean-going propeller-driven iron ship and was an engineering triumph of Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-59), creator of the Clifton Suspension Bridge, and the Great Western, an oak built paddle steamer.14 Hocken was fortunate to travel on three voyages on the SS Great Britain: Liverpool to Melbourne 17 February to 1 May 1861; Melbourne to Liverpool 30 May to 3 August 1861; and Liverpool to Melbourne 20 October to 24 December 1861. For each voyage, shipboard newspapers were created, which Hocken frequently contributed to. In fact, two of three titles at the SS Great Britain Archives were once his, given to the Archives some years ago by his only daughter Gladys. These items are signed and annotated by Hocken, and importantly represent the first printed items he actually collected (see Appendix vi). Thus his salvaging began in 1861, as did his writing. From annotations on the content page of The Great Britain Magazine and Weekly Screw there are revealed his contributions: ‘health reports’ (an expected obligation to boost morale), ‘Sea-sickness’, ‘The World We Inhabit’ (a serial contribution), ‘Eyes’, ‘A Story of Un-True Love’, and (presciently) an article on the Maori and Maori mythology. His article on ‘Sea-sickness’ was a leader to a more detailed article in The Lancet, October 1861, which was another find in Dublin. The article represents Hocken’s first appearance in print. Beata Bradford, Archivist, was kind enough to supply photocopies of these extremely scarce newspapers: The Great Britain Magazine and Weekly Screw; The Great Britain Gazette; and The Cabinet. In addition, she extracted from containers (current refurbishment of the Archives meant that everything was in containers, including, temporarily, one visiting researcher) four manuscript accounts of trips taken on the SS Great Britain. One – by Dr Samuel Archer – helped contextualise Hocken’s ship’s surgeon experience, while three others 14 See Adrian Ball, Is Yours an SS Great Britain family? (Emsworth, Hampshire Mason, 1988). 15 were directly related to the trips Hocken made.15 One I knew about: Rachel Henning’s letters concerning Hocken’s first voyage.16 The other two were unknown: John Worthing Pritchard’s brief transcription of the 20th Voyage, 30 May to 3 August 1861, and Charles Albert Chomley’s ‘Full True and Particular Account of the Voyage of the Good Steam Ship Great Britain from Melbourne to Liverpool…30 May - 3 August 1861. The latter was particularly good, describing life on board, confirming passenger deaths, icebergs seen, and shipboard activities such as Hocken playing ‘Vincent’ in a shipboard play, his nom de plume of Professor Swyzel in the Great Britain Gazette, and his dining table companions including Captain Lyttleton, Captain Pasley, Mr Malpas, Mr Wildash, Gray, the head Captain, and Chomley (see Appendix vii, viii, and ix). 10. Oxford There was very little research time allocated for Oxford. After the necessary but lengthy interview for access to the Bodleian collections, and explanations of their whereabouts (massive refurbishment is occurring), Dr Garnett and Andrew Lang materials were viewed. Unfortunately, there was no mention of Hocken in these papers. 11. London a. British Library The British Library houses manuscript materials relating to Andrew Lang, Augustus Petherick (bookseller), Dr Garnett, and Sir Frederick Young. The last three corresponded with Dr Hocken. While nothing of value arose out of reading these files, the biggest find was when trawling through the Day Books of Bernard Quaritch, the reputable antiquarian book dealer in London. These volumes contain names of individuals who purchased books. In the ‘Asia, Diary of Samuel Archer MRCS. Voyage 13 Liverpool – Melbourne – Liverpool 16.2.57 – 24.8.57. SS Great Britain Archive, Bristol. 16 The Letters of Rachel Henning. Edited by David Adams (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1966). 15 16 Africa, Australia 1899’ ledger (MS. Add. 64221) there was written ‘Dr Hocken’, with Moray Place scored out and ‘The Octagon’ replacing it. In the margin were notes: ‘‘F.A.’ and ‘New Zealand’ and ‘Old Colonial Newspapers’. Significantly, other New Zealand customers were listed, and their presence offers a window into the world of 19th century book collecting in New Zealand. Other Dunedin collectors (and their institutions) included: ‘Geo Austin (in England) & no good’; ‘Botanic gardens: Wm Blaxland Benham (Zoology)’; ‘Rev A.R. Fitchett (Girls High School crossed out)’; ‘Otago Institute Prof Parker (dead)’; ‘A. Hamilton J Rathay 17 Bond Street’; ‘Joseph Wood Supreme Court Library’; ‘Geo M. Thomson, The Rectory’; and ‘A. Wilson Girls High School’. Sir George Grey’s name is recorded with the word ‘dead’ written above and then ‘in England’. Robert McNab is listed under Invercargill, along with Dr Young and the Southland Institute. Alexander Turnbull is listed under Wellington along with Elsdon Best, John Ward, and the Wellington Museum (Sir James Hector). In a volume dated 1882, I came across a record of Hocken buying his copy of Angas’s New Zealanders Illustrated, and then further on, a list of 12 items purchased. This find was particularly significant in that it proved that Hocken also obtained books from more traditional and established book sources. b. Linnean Society, Burlington House, Piccadilly, London Dr Hocken became a member of the Linnean Society (London) in 1882. In the Society’s correspondence files I discovered one letter written by Hocken that was mis-attributed, and one by Hocken’s second wife, Elizabeth Mary. In addition, the Librarian (Lynda Brooks) let me trawl through Minutes Books of the Society, in which was discovered a 1902 announcement (whether rightly or not) by Hocken that visiting members of the Linnean Society could travel through New Zealand ‘at special rates to visit the celebrated scenery 17 [which] will be afforded by the New Zealand Government.’17 The letter verified his desire for completeness of the Linnean Society Transactions; the announcement showed that when possible he was an active member of the Society. The most tangible evidence of this is his exlibris bookplate, which has either a hand-written or printed ‘F.L.S’ on it. c. The Japan Society When in London in 1902, Hocken joined the Japan Society as a corresponding member. While his nominators are known for membership to the Linnean Society and the Royal Anthropological Society, there are no records of such for the Japan Society. The Minutes of the Council of the Japan Society are certainly available, but for some unknown reason specific details of his particular nominators are not registered, whereas (annoyingly) others are. However, the records did reveal who was present at the 11 June 1902 General Meeting, and Arthur Diósy, Chairman at the time, must have been involved in signing off Hocken’s membership. Visitor autograph books were also kept, but surprisingly, for one who liked to sign his name to books, Hocken’s name is not present. He is however listed in the ‘Japan Society London Address book 1904-05’: ‘Hocken, Thomas Morland; M. D. F.L.S. Dunedin, New Zealand; Elected 1902. (Corr.)’.18 d. Royal Anthropological Institute, 50 Fitzroy St London Because of Hocken’s interest in ethnology and anthropology, especially relating to Māori in New Zealand, he joined the Royal Anthropological Society (London). His nominators were James Edge-Partington, and Henry Balfour, Curator, Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford University. Subsequently uncovered in the Records and Minutes of the Society, Hocken (listed fulsomely as Dr T. M. Hocken Esq., M.R.C.S, F.R.G.S, F.L.S.) was nominated as an ordinary member 17 General Minute Book No.12 1898-1906 Linnean Society. London. Here the use of M.D. is incorrect. Hocken was not an M.D. This is a title which is usually given to a University trained doctor. 18 18 (along with eight others) on 27 October 1903 and then elected on 10 November 1903.19 Hocken’s friend Augustus Hamilton was a corresponding member; other members with whom he corresponded included Professor E. H. Giglioli, Professor Baldwin Spencer, Professor Tsuboi (whom he met in Japan), and Andrew Lang. Edge-Partington, author of An Album of the Weapons, Tools, Ornaments, Articles of Dress of the Natives of the Pacific Islands (1890), gave Hocken formal thanks for supplying photographs of particular pieces in his Series III of the above publication. Edge-Partington’s ‘Geographical Register of Objects from the Pacific’ was also perused in the RAI Collection. Hocken met Edge-Partington in London a number of times, and a copy of Edge-Partington’s own Random Rot (1883) was presented to Hocken with the note: ‘in remembrance of his too short visit to Little Wymondley, 23 November 1903.’20 Also discovered was a letter written by Elizabeth Hocken in 1912, concerning payment for the journal Man and notification that future accounts be sent to W. H. Trimble, the first Hocken Librarian. Chance remarks can often be rewarding. On talking to Sarah Walpole, archivist, about Hocken’s position as ship’s surgeon on the SS Great Britain, she revealed that the American artist George Catlin had proposed in 1851 that the ship be made into a floating Ark of Mankind. My disbelief was dismissed when she showed me (and copied) RAI correspondence verifying this fact. 4. The Trail Documented… When and where possible, I took photographs: Stamford (Hocken’s birthplace); Woodhouse Grove School; and his residences at Blackett Street (now a clothes shop) and Westgate Street (now a store called Pinnochio), Newcastle. In 1902, Hocken stayed at 7 Leazes Terrace, a fashionable part of town.21 He was adverse to sporting activities, and did not collect books on 19 Council Minutes 1900-1902 of the Royal Anthropological Institute A 10: 3. London. James Edge-Partington to Hocken, 12 November [1903]. MS-0451-016/008. Copy of Random Rot. Hocken Library. 21 The Terrace was designed and built in 1830 and was considered a well-to-do fashionable residential area. It is now used as a self-catering postgraduate student accommodation by Newcastle University. 20 19 that subject because (as he believed) such activities wasted time. Ironically, Leazes Terrace fronts on to St James’s Park Stadium, home ground of Newcastle United Football Club since 1892 and used for that purpose since 1880. One wonders what Hocken thought as he looked out on the park and watched early 20th century soccer fans training (see Appendix x). Peter Street, Dublin, was a brief walk from the Mercer Library. It was photographed, even though the Adelaide Hotel now stands where the School once was. Dr Hocken was a small man, and by way of compensating, he would offer his hand to the tallest lady on the SS Great Britain and walk her around the promenade deck. The SS Great Britain Trust continue to refurbish the ship. This has included a mock-up of the Doctor’s quarters, galleys, and reconstruction of the large dining room. Numerous photographs were taken of this famous ship, including the deck. In all his correspondence in London during 1902-04, Hocken gives his residence at 40 Kildare Terrace, Westbourne Grove; this fine terraced house still stands and was photographed (See Appendix xi). His residence at 28 Euston Square (in 1882) is now the frontage of Euston Station, and photographs were taken of the entrance to the Linnean Society (London) in fashionable Burlington Square; it is unchanged from his visits there (see Appendix xii). 5. Omissions a. Methodist Archive, John Rylands University of Manchester A regret on this trip was not getting to the Methodist Archives at John Rylands. A Bank Holiday caused one disruption and travel schedules meant that Saturday was the only day I had available to visit this library. Unfortunately, Saturday meant skeleton staff and manuscript materials and rare books could not be called up unless specifically ordered the day before. A vague idea of their huge ‘Methodist Archive’ was far too general and not specific enough. 20 However, comforted by the fact that the material I had obtained at Lincolnshire Archives and Grimsby was far more than I required on the Rev. Joshua Hocken, the Methodist Church and their circuits, and Hocken’s early life, I made a percentage call. Indeed, the realities are that one cannot do it all. Another allied regret was that I did not meet Dr Peter Nockles at Rylands. He and I have corresponded over Methodist and other Victorian matters and it would have been great to put a face to a name. I also failed to re-kindle a friendship with Rylands manuscript curator John Hodgson, whom I had met before. Although not pertinent to Hocken, but allied to my professional work, I also missed the chance to see the largest collection of printed Caxton’s in any English institution. As mentioned, one cannot do it all. b. Grimsby and Newcastle While I certainly got to Grimsby and Newcastle, sickness and broken library shifts meant that I failed to meet Jennie Mooney (Grimsby Public Library) and Derek Tree (Newcastle Public Library). Prior to my arrival, both had been incredibly helpful via email. It would have been good to thank them in person. 6. Research Caveat No.1: It is vital that contact be made with institutions prior to arrival, and where possible arrangements for materials to be used set in place. Letters of introduction and proof of identity (passports, and in some cases spare photographs) are also necessary to facilitate access. Failure to do so can often impede progress. No.2: Even though prior warning is given on what is requested, the research process can be incredibly frustrating. There are unfamiliar processes to come to terms with, the where to go if collections and their placement are unknown, the fixed retrieval times (solved by planning), 21 and occasionally, the unavailability of staff. In fact, not finding anything after hours of searching can jaundice even the best researcher. At one institution, I had to reschedule my research because the Archivist was away sick. Only she could access the desired materials. Patience and flexibility are key attributes. No. 3: There is a real danger of trying to do too much. As a visiting researcher, one is often in a certain place for a limited amount of time and then only once. This inevitably places pressure on what can be achieved and when. A frantic rush can result, especially if travel is involved: tubes, trains, etc. If patience and flexibility are vital attributes, so is planning wisely and being realistic on what can be achieved. No.4: I found it necessary to have coins always available (for lockers), additional passport photographs, and additional reading material for the long wait (interviews, waiting for items to be retrieved). There were often occasions when it was necessary to pay for the privilege of using a collection. While grumbling (quietly) was perhaps justified, failure to comply meant no access. 7. Prime Benefits of Research Following the ‘Hocken Trail’ in England and Ireland not only confirmed details known about Dr Hocken, but also enabled the discovery of information that fleshes out aspects of his early life, education, contemporaries, and his book collecting. Essentially, the trip allowed revealed discoveries, confirmations, and contextualization. Although mentioned in the narrative above, they are briefly: 22 Discoveries Family accounts through Methodist Archives Grounding the Hocken family in particular places and times The Rev. Hocken’s roster for Methodist circuits in Stamford and Grimsby Obtaining a copy of the Rev. Hocken’s first book Photographs of Hocken’s residences in Newcastle Images of the Practical School of Science, Newcastle Images of the ‘Original’ School of Medicine, Dublin Address to Hocken on first day attendance as a student of surgery, Dublin Study regime faced by Hocken as a student of surgery, Dublin First printed items collected - Hocken’s own copies of shipboard newspapers First appearance in print – The Lancet, October 1861 Two contemporary accounts of voyages on the SS Great Britain Hocken as a buyer of books from Quaritch, antiquarian booksellers, London Hocken’s input into Linnean Society (London) Confirmations Hocken’s baptism records The Rev. Joshua Hocken’s Methodist circuits Information on lecturers and courses at Practical School of Science, Newcastle Information on lecturers and courses at Original School of Medicine, Dublin Hocken as a Meath Hospital student, Dublin Hocken as a ship’s surgeon on SS Great Britain Hocken’s input as contributor to shipboard newspapers As a member of the Japan Society, London 23 As a member of the Royal Anthropological Institute Contextualization Hocken’s birthplace - Stamford Methodist circuit histories, Methodism, family life – Stamford, Lincoln, Grimsby Hocken’s school – Woodhouse Grove Hocken’s time in Newcastle Hocken’s time in Dublin Hocken’s residences in Newcastle, and London Life on board SS Great Britain The findings from the trip will be woven into my book on Dr Hocken as a book collector, a bio-bibliographic publication of some 22 chapters. Hopefully when published, it will not only remind individuals of the wealth of material he collected, but it will add to the store of knowledge about collectors in New Zealand. It is hoped that articles will also appear in journals such as the Bulletin of the Bibliographical Society of Australia and New Zealand, the Turnbull Library Record, and the Book Collector (UK) that will further disseminate Hocken’s activities as a collector. Research and scholarship has always been strongly reliant on collectors and collecting. It is hoped that the work will add to the store of knowledge about collectors in New Zealand and induce others to undertake similar projects on them. There is a wealth of them that need similar attention, e.g. Robert McNab; A. H. Reed; Henry Shaw, H. Fildes, William Downie Stewart. It will also increase an awareness and understanding of the development of New Zealand’s heritage and culture. 24 8. By-products of Research a. ‘Flying the Flag’ In the recent past I have delivered a number of talks on Dr Hocken that have not only helped consolidate a specific aspect of my work on Dr Hocken, but by delivery raised an awareness of Dr Hocken’s contribution to scholarship. Before I left, I offered my services to libraries and institutions in the UK and initially there were five who were interested in such an event: Friends of King’s College, Cambridge, Woodhouse Grove School, the Japan Society, Trinity College, Dublin, and the National Library of Ireland, Dublin. In reality, I gave two. Through the kind efforts of Dr Joseph Marshall, Rare Books Librarian, University of Edinburgh, I gave an open lecture on ‘The Deep South Revealed: Treasures from Special Collections, University of Otago, Dunedin’. It was a well attended and a fruitful session, and offered the opportunity to re-meet Print Culture colleagues: Dr Bill Bell (University of Edinburgh), Dr David Finklestein (Queen’s University), and visiting University of Otago lecturer Dr Noel Waite. Through the kind efforts of Heidi Potter, Librarian at the Japan Society, I gave an open lecture at Quaker House, Euston Road, on ‘Dr Hocken and his Japanese Experience, 1901-04’. It was well attended; some 45 people. Knowing how difficult it is to schedule such events, I was very pleased with what was achieved. It certainly raised the profile of the University of Otago and Dr Hocken, and the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust, whom I gave formal thanks in each delivery. b. Institutional Access and Liaison One tangible benefit of writing a biography on a book collector was entrée to behind the scenes of various libraries and institutions. I was extremely fortunate to meet librarians, curators, and archivists who not only took the time to show off their treasures, but they were extremely interested in my research on Dr Hocken. Dr Christopher de Hamel, who started his 25 own career as a world-wide expert on medieval manuscripts through a relationship with A. H. Reed at the Dunedin Public Library, is now the Parker Librarian at Corpus Christi, Cambridge. Not only did de Hamel introduce me to the rituals of Evensong and High Table at Corpus Christi (where I sat next to a Professor of Hebrew, and Professor Chris Andrews, whose book on MI5 (The Defence of the Realm) has just been published), but the following day he revealed some of the treasures of Archbishop Parker’s Library. They included a letter written by Anne Boleyn, a manuscript owned by Thomas A’Beckett, and manuscript documents detailing the last rites and deaths of Bishops Latimer and Ridley, and Archbishop Cramner. De Hamel also had a manuscripts exhibition on that depicted the first pictorial illustrations of an elephant. Professor David McKitterick, Wren Librarian, Trinity College Library, Cambridge also highlighted some parts of the Trinity collection. This included a rather amusing anecdote about the rejected statue of Lord Byron, the ‘rude’ stained-glass window art covered by the prudish Victorians, A.A. Milne’s manuscript of Winnie the Pooh, medieval manuscripts, manuscript poems by Lord Tennyson, and works by Ludwig Wittgenstein. Special Collections, University of Otago, has a number of typescript ‘Blue Books’ by Wittgenstein and McKitterick was intrigued by these. This has facilitated further contact. The University of Otago has a strong connection with the University of Durham. On the way to Newcastle, I was fortunate to visit the Cathedral and University of Durham Library, Palace Green, Durham. Special Collections Librarian Jane Hogan and Alastair Fraser, rare book cataloguer, showed me the treasures of the library, which included the Cosin Library, the Bamburgh Library, the Routh Library (the result of 90 years of collecting), and their large Sudanese Archive. Notable items seen included an early edition of Ptolemy, Jenson’s Pliny, two medieval manuscripts, and a number of Shakespeare quartos. 26 Dr Marshall, Special Collections, University of Edinburgh, also show-cased a number of ‘Treasures’ from his collection, which included a 10th century English manuscript (the oldest one in Scotland), Arabic and Middle Eastern manuscripts, and the Scottish Philosopher David Hume’s library. During the viewing, there was discussion on problems (and solutions) common to Special Collections world-wide: reader numbers, digitisation, latest purchases, and the effect on morale through a new library (Special Collections, University of Edinburgh, has just been refurbished). The National Library of Scotland was also visited, and their interactive, permanent exhibition of the John Murray Archive was enormously interesting. Dr Annette Hagen, rare books curator, was excellent in that I heard another angle on the ‘State of the Nation’ in the rare books world in Scotland. A break from research was a visit to Trinity College Library, Dublin, where I met Robin Adams (University Librarian), and Charles Benson (Head of Rare Books). Not only was collegiality fostered – talking about exhibitions, the ‘State of the Nation’ of rare books in New Zealand, cataloguing rare books, etc – but it afforded time to see the Book of Kells. As a librarian working with medieval manuscripts and rare printed books, this was a real treat. The famed Marsh’s Library was also visited. Now under the Keepership of Muriel McCarthy, it remains as it was when first established in 1701. We talked about exhibitions, books, promotional activities, and catalogues, with the double treat of her latest exhibition based around Lewis Carroll’s Jabberwock. While at the British Library, I had meetings with John Goldfinch, Incunabulist, and Nicholas Martland, Australia and New Zealand Books Curator. I also managed to see their fine Maps Exhibition, and permanent Treasures display. I also managed to see Mark Richards, Chairman of the Lewis Carroll Society, London, because of the University of Otago’s Otakou Press publication of The Hunting of the Snark (2006), and Nicolas Barker, editor of The Book Collector. He has asked for an article on Hocken for this publication. 27 9. Conclusion The opportunity to travel to the United Kingdom and undertake the research on Dr Hocken was extremely useful on various fronts. The discoveries and the confirmations speak for themselves. I am already re-writing chapters and the finds and confirmations have already had an impact on the narrative. In some instances, there is so much more now that can be said, for example, the Methodist circuit life that the Hocken family were involved in. I am also able to write more definitely about the realities of Hocken’s past life before he arrived in New Zealand in 1862, some of which has not been acknowledged at all in any previous work. While some of these findings can be judged as minutiae, they nevertheless add to the store of information surrounding him. Such details are important. The contextualization process was also illuminating. While not producing anything tangible, the fact that I was able to see Hocken’s birthplace and his old school, for example, aids the process of writing. I can now write confidently about those places and hopefully portray a true and firmer picture of his early life. I acknowledge that not to see them would be a real gap, and special thanks is given to the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust for providing the opportunity to make it real and reduce that deficit. One delightful aspect to the trip was collegiality and liaison with other library and institutional professionals. Throughout the research process I found the librarians, curators, and archivists extremely welcoming and importantly to the research process, helpful. Indeed, it was gratifying to experience the interest expressed by British library colleagues in my research topic, the wider area of libraries in New Zealand, and further still, New Zealand as a country and destination. The names below acknowledged convey something of the individuals met, their institutions, and towns and cities visited and enjoyed. Overall, the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust gave me a rich and valuable experience. It is one that I would encourage others to apply for, and one that I would heartily repeat. 28 10. Acknowledgements In the search for relevant materials on Dr Hocken, I have been helped by many people from numerous institutions. It is a pleasure to acknowledge them here. Thanks to John Cardwell, Librarian of the Royal Commonwealth Manuscript Collection, Dr Christopher de Hamel, Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, Prof. David McKitterick, Wren Librarian, Trinity College, Cambridge, Carol Tasker and James Stevenson, Lincolnshire Archives, Jennie Mooney, Grimsby Public Library, Hugh Knowles and Julian Bolt, Woodhouse Grove School, Yorkshire, Jane Hogan and Alastair Fraser, Special Collections, University of Durham, Derek Tree, Newcastle Public Library, Dr Melanie Wood, Special Collections, University of Newcastle, Dr Joseph Marshall, Special Collections, University of Edinburgh, Dr Annette Hagen, National Library of Scotland, Mary O’Doherty, Mercer Library, Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland, Robin Adams and Charles Benson, Trinity College, Dublin, Brid O’Sullivan, National Library of Ireland, Muriel McCarthy, Marsh’s Library, Dublin, Beata Bradford, Archivist, SS Great Britain Archives, Bristol, Colin Harris, Bodleian Library, Oxford, John Goldfinch and Nicholas Martland, British Library, Sarah Walpole, Royal Anthropological Institute, London, Lynda Brooks, Linnean Society (London), Heidi Potter, Japan Society, London, and Nicolas Barker. Sincere thanks to the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust for granting financial assistance that enabled me to undertake the research trip. And finally, special thanks to the Management team of the University of Otago Library for their on-going support and contributions towards this project. 29 11. Appendix I: Pictures i. Stamford, with the River Welland running through it. ii. The Railway Bridge and the River Aire, running along the boundary of Woodhouse Grove School, Yorkshire 30 iii. iv. The Coronation Clock, Woodhouse Grove School, Yorkshire Hocken’s award in Botany v. Proposed Rules of the College of Practical Science in in Denis Embleton’s Papers at the University of Newcastle 31 SS Great Britain, Bristol vi. vi. The Great Britain Magazine and Weekly Screw vii. Deck of the SS Great Britain viii. ix. Discharge certificate, similar to what Hocken would have received in December 1861 Bill of fare, August 1861 32 x. 7 Leazes Street, Newcastle, Hocken’s residence in 1902 xi. 40 Kildare Terrace, Bayswater, Westminster, Hocken’s residence while in London in 1902-04. xii. Linnean Society, Burlington Square, London 33 12. References Manuscript Collections: Great Britain Bristol SS Great Britain Archive: Diary of Samuel Archer MRCS. Voyage 13 Liverpool – Melbourne – Liverpool 16.2.57 – 24.8.57. Charles Albert Chomley, ‘Full True and Particular Account of the Voyage of the Good Steam Ship Great Britain from Melbourne to Liverpool…30 May - 3 August 1861’. John Worthing Pritchard, ‘Transcription of the 20th Voyage, 30 May to 3 August 1861’. SS Great Britain newspapers: The Great Britain Magazine and Weekly Screw; The Great Britain Gazette; and The Cabinet. Cambridge University Library, Manuscript Department: Richard Garnett, Letters to Lord Acton, 1877-1901. Ref Add MSS 6443, 8119. Andrew Lang, c.1906-11: letters to Sir Sydney Roberts Reference MS Add.9784; Letters and enclosure to W Robertson Smith. Reference Add 7449/D381-90. Royal Commonwealth Collection: Sir Frederick Young RCMS 54; RCMS 278/45. Dublin Mercer Court Library: Archive Collection Minute Book for Ledwich Medical School The Kirkpatrick Archives National Library of Ireland: Freeman’s Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser Rare Books Collection Edinburgh University Library, Special Collections Division: Andrew Lang: circa 35 letters. George Dempster of Dunnichen Reference E2001.30 and c1912: letters (10) to Charles Sarolea. Reference Sar coll 23. Grimsby Public Library – Local History Section: Local History books The Skelton Bills and Poster Collection on microfilm Stamford Mercury on microfilm Lincoln Lincolnshire Archives: Meth B/Stamford/13/1; Circuit Steward’s account book 1805-1836 (Meth B/Grimsby/13/1; MethB/Grimsby/13/2: Quarterly Meeting Grimsby Accounts 1838-1872 Public Record Office on microfilm Church of England records of Stamford Churches on microfiche Index cards to the Stamford Mercury 34 Lincoln Public Library Joshua Hocken, Brief History of Wesleyan Methodism (1839). London British Library - Manuscripts Richard Garnett Collection: c1889-1897: letters to W.A. Copinger. Reference Add MSS 62551 Letters to John Lane. Reference Add MS 71496; 1886-1903: letters (11) to TJ Wise. Reference Ashley MSS Andrew Lang: 1886-1905: corresp with William Archer. Reference Add MS 45293 ff1-20 Bernard Quaritch Collection: MS Add. 64, 132-64, 217; 64,221 Sir Frederick Young 1904-05: letters to WH Griffin. Reference Add MS 45564 Linnean Society (London) Correspondence General Minute Book No.12 1898-1906. Royal Anthropological Institute Council Minutes 1900-1902 of the Royal Anthropological Institute A 10: 3. General Correspondence file A18 : A18/*554 E.W. Martindell, assistant secretary, to W. Trimble, 17 Jan. 1912, with letter to RAI attached from Elizabeth Mary Hocken, 7 January 1912. James Edge-Partington, ‘Geographical register of objects from the Pacific.’ MSS 205, 339 Japan Society Minutes of Society Newcastle Public Library Photograph Collection Newspaper Collection University, Robinson Library Denis Embleton, Papers relative to College of Medicine. University Archive, Ref: 16/2/1 Newcastle Medical and Surgery Minute book 1851-73 Practical School of Science: Entry and Registration Book 1851/2-1860 Oxford Bodleian Library Richard Garnett Collection: 1875-1903: letters to Edith Clarke. Reference MS Eng lett c 582; 1895-1902: letters (11) to Sidney Lee. Reference MS Eng misc d 177; Andrew Lang - letters (11) to Sidney Lee. Reference MS Eng misc d 178; c1889-1911: letters to Gilbert Murray. Bodleian Library, Oxford. NB: Most of the above names were sourced by reading through Hocken’s in-coming correspondence at the Hocken Library, his papers, and a physical examination of all his books, manuscripts and art collection. 35 Printed Sources Ball, Adrian, Is Yours An SS Great Britain Family? Emsworth: Hampshire Mason, 1988. Davies, Rupert E., Methodism. Petersborough: Epworth Press, 1985. Hocken, A.G., Dr Hocken of Dunedin: A Life. Easting Riding, North Otago: The Author, 2008. Holy Bible, Oxford Edition, 2000. Letters of Rachel Henning. Edited by David Adams. Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1966. Lester, George, Grimsby Methodism (1743-1889) and the Wesleys in Lincolnshire. London: Wesleyan-Methodist Book-Room, 1890. Lock, John Lock and Canon W. T. Dixon, A Man of Sorrow. The Life and Times of the Rev. Patrick Brontë 1777-1861. London: Nelson, 1965. Kerr, Donald, Amassing Treasures for All Times: Sir George Grey, Colonial Bookman and Collector. New Castle, Del.: Oak Knoll Press ; Dunedin, N.Z. : Otago University Press, 2006 McCormick, Eric, The Fascinating Folly: Dr. Hocken and His Fellow Collectors. Dunedin: University of Otago Press, 1961. ____, Alexander Turnbull: His Life, His Circle, His Collections. Wellington: Alexander Turnbull Library, 1974. Medical Directory and General Medical Register for Ireland 1859. London: John Churchill, [1859]. Medical Register. 1860 (London, 1860). Medical Students Guide Containing the Latest Regulations of all the Licensing Medical Corporations of Great Britain and Ireland. Dublin: Fannin and Co, [1855]. Lambert Hepenstal Ormsby, Medical History of the Meath Hospital and County Dublin Infirmary. 2nd ed. Dublin: Fannin & Co, 1892. F.C. Pritchard, The Story of Woodhouse Grove School. Bradford, England: Woodhouse Grove School, 1978. J. T. Slugg, Woodhouse Grove School: Memorials and Reminiscences. London: Published for the Author, T. Woolmer, 1885. H. W. Starkey, A Short History of Woodhouse Grove School 1812-1912. Bradford: W. N. Sharpe, 1912. Woodhouse Grove School. Reminiscences, 1812-83. Bradford: Printed and published for the Centenary Celebration Committee, 1912. 36