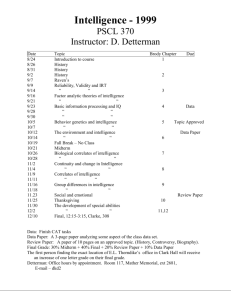

Exercises: J. Geffen

advertisement

Testing the Science of Intelligence By: Geoffrey Cowley From: Newsweek, October 24, 1994 Exercises: J. Geffen 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 1. If you’ve followed the news for the past 20 years, you’ve no doubt heard the case against intelligence testing. IQ tests are biased, the argument goes, for they favor privileged whites over blacks and the poor. They’re unreliable, because someone who scores badly one year may do better the next. And they’re ultimately worthless, for they don’t predict what a person will actually achieve in life. Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray defy that wisdom in “The Bell Curve”, and they’re drawing a predictable response. The New York Times Magazine asks whether they’ve “gone too far” by positing race- and class-based differences in IQ. A Harper’s editor, writing in The New Republic, places Herrnstein and Murray within an “eccentric and impassioned sect,” whose view of IQ and inequality is out of touch with “mainstream scientific thinking.” A columnist for New York Magazine notes that “the phrenologists thought they were onto something, too.” 2. The rush of hot words is hardly surprising, in light of the book’s grim findings and its baldly elitist policy prescriptions. But as the shouting begins, it’s worth noting that the science behind “The Bell Curve” is overwhelmingly mainstream. As psychologist Mark Snyderman and political scientist Stanley Rothman discovered in a 1984 survey, social scientists have already reached a broad consensus on most points in the so-called IQ debate. They may disagree about the extent to which racial differences are genetically based, and they may argue about the prospects for narrowing them. But most agree that IQ tests measure something real and substantially heritable. And the evidence is overwhelming that IQ affects what people accomplish in school and the workplace. In short, cognitive inequality is not a political preference. It’s a simple fact of life. Problem solving: 3. Mental testing has a checkered past. The tests of the 19th century were notoriously goofy, concerned more with the shapes of people’s skulls than with anything happening inside. But by the turn of the 20th century, psychologists had started measuring people’s aptitudes for reasoning and problem solving, and in 1904 the British psychologist Charles Spearman made a critical discovery. He found that people who did well on one mental test did well on others, regardless of their content. He reasoned that different tests must draw on the same global capacity, and dubbed that capacity g, for general intelligence. 4. Some psychologists have since rejected the concept of g, saying it undervalues special talents and overemphasizes logical thinking. Harvard’s Howard Gardner, for example, parses intelligence into seven different realms, ranging from “logicalmathematical” to “bodily-kinesthetic.” But most of the 661 scholars in the Snyderman Testing the Science of Intelligence / 2 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 survey endorsed a simple g-based model of mental ability. No one claims that g is the only thing that matters in life, or even in mental testing. Dozens of tests are now published every year. Some (like the SAT) focus on acquired knowledge, others on skills for particular jobs. But straight IQ tests, such as the Wechsler Intelligence Survey, all draw heavily on g. 5. The Wechsler, in its adult version, includes 11 subtests and takes about an hour and a half. After recalling strings of numbers, assembling puzzles, arranging cartoon panels and wrestling with various abstractions, the test taker gets a score ranking his overall standing among other people his age. The average score is set at 100, and everyone is rated accordingly. Expressed in this currency, IQs for a whole population can be arrayed on a single graph. Roughly two thirds of all Americans fall between 85 and 115, in the fat midsection of the bell-shaped curve, and 95 percent score between 70 and 130. 6. IQ scores wouldn’t mean much if they changed dramatically from year to year, but they’re surprisingly stable over a lifetime. IQ at 4 is a good predictor of IQ at 18 (the link is nearly as strong as the one between childhood and adult height), and fluctuations are usually negligible after the age of 8. For reasons no one fully understands, average ability can shift slightly as generations pass. Throughout the developed world, raw IQ scores have risen by about 3 points every decade since the early part of the century, meaning that a performance that drew a score of 100 in the 1930s would rate only 85 today. Unfortunately, no one has discovered a regimen for raising g at will. Genetic factors: 7. Fixed or not, mental ability is obviously a biological phenomenon. Researchers have recently found that differences in IQ correspond to physiological differences, such as the rate of glucose metabolism in the brain. And there’s no question that heredity is a significant source of individual differences in IQ. Fully 94 percent of the experts surveyed by Snyderman and Rothman agreed with that claim. “The heritability of IQ differences isn’t a matter of opinion,” says University of Virginia psychologist Sandra Scarr. “It’s a question of fact that’s been pretty well resolved.” 8. The evidence is compelling, but understanding it requires a grasp of correlations. By computing a value known as the correlation coefficient, a scientist can measure the degree of association between any two phenomena that are plausibly linked. The correlation between unrelated variables is 0, while phenomena that vary in perfect lock step have a correlation of 1. A correlation of .4 would tell you that 40 percent of the variation in one thing is matched by variation in another, while 60 percent of it is not. Within families, the pattern among test scores is striking. Studies find no IQ correlation among grown adoptive siblings. But the typical correlations are roughly .35 for half siblings (who share a quarter of their genes), .47 for full siblings (who share half of their genes) and .86 for identical twins (who share all their genes). Testing the Science of Intelligence / 3 Rethinking the Mind 80 85 90 95 100 105 110 115 1575: Spanish physician Juan Huarte defines intelligence as the ability to learn, exercise judgment and be imaginative. 1839: American physician Samuel George Morton champions “craniometry” – the measurement of skull and brain size to determine the intelligence of different races. 1859: Charles Darwin publishes “Origin of Species,” arguing in part that intelligence is heritable. 1904: British psychologist Charles Spearman discovers that people who do well on one type of intelligence test do well on others – a trait he calls g, for general intelligence. 1905: French psychologist Alfred Binet develops the first intelligence test involving analogies, patterns and reasoning skills. 1912: German psychologist W. Stern proposes the “intelligence quotient” – mental age divided by chronological age. 1912: Henry H. Goddard, inventor of the word “moron”, administers intelligence tests to immigrants at Ellis Island. 1917: The US Army begins administering IQ tests to large groups of recruits. 1938: Developmental psychologist Jean Piaget asserts that intelligence arises from both environmental and biological factors. 1966: Nobel-Prize-winning physicist William Shockley advocates sterilization for people with low IQs and supports a sperm bank for geniuses. 1969: Educational psychologist Arthur Jensen writes that programs like Head Start fail because many of the participants have fixed, low IQs. 1971: American psychologist Richard Herrnstein asserts that social and economic standing are tied to heritable differences in IQ. The US Supreme Court outlaws the use of IQ tests as a hiring tool in most cases. 1981: American biologist Stephen Jay Gould writes “The Mismeasure of Man,” blasting past and present intelligence testing as unscientific. 1990: The Minnesota Twin Study finds evidence of a strong genetic component in many psychological traits, including IQ. 9. So how much of the variation in IQ is linked to genetic factors and how much to environmental ones? The best way to get a direct estimate is to look at people who share all their genes but grow up in separate settings. Four years ago, in the best single study to date, researchers led by University of Minnesota psychologist Thomas Bouchard published data on 100 sets of middle-aged twins who had been raised apart. Testing the Science of Intelligence / 4 120 125 130 135 140 145 150 155 These twins exhibited IQ correlations of .7, suggesting that genetic factors account for fully 70 percent of the variation in IQ. 10. Obviously, that figure leaves ample room for other influences. No one denies that the difference between a punishing environment and an adequate one can be substantial. When children raised in the Tennessee mountains emerged from premodern living conditions in the 1930s, their average IQ rose by 10 points. But it doesn’t follow that the nongenetic influences on IQ are just sitting there waiting to be tapped. Scarr, the University of Virginia psychologist, has found that adoptees placed with educated city dwellers score no better on IQ tests than kids placed with farm couples with eighth-grade educations. As long as the environment is adequate,” she says, “the differences don’t seem to have much effect.” 11. Worldly success: IQ aside, qualities like motivation and diligence obviously help determine what a person achieves. People with low IQs sometimes accomplish great things – Muhammad Ali made the big time with an IQ of 78 – but rare exceptions don’t invalidate a rule. The fact is, mental ability corresponds strongly to almost any measure of worldly success. Studies dating back to the 1940s have consistently found that kids with higher IQs complete more years of school than those with lower IQs – even when they grow up in the same households. The same pattern emerges from studies of income and occupational status. 12. Can IQ be used to predict bad things as well as good ones? Until now, researchers haven’t focused much on the role of mental ability in social problems, such as poverty and crime, but “The Bell Curve” offers compelling new data on that front. Most of it comes from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY), a study that has tracked the lives of 12,000 young people since 1979, when they were 14 to 22 years old. The NLSY records everything from earnings to arrests among people whose IQs and backgrounds have been thoroughly documented. The NLSY participants come from various racial and ethnic groups. But to keep the number of variables to a minimum, Herrnstein and Murray looked first at how IQ affects the social experience of whites. Their analysis suggests that although growing up poor is a disadvantage in life, growing up with low mental ability is a far greater one. 13. Consider the patterns for poverty, illegitimacy and incarceration. Poverty, in the NLSY sample, is eight times more common among whites from poor backgrounds than among those who grew up in privilege – yet it’s 15 times more common at the low end of the IQ spectrum. Illegitimacy is twice as common among the poorest whites as among the most prosperous, but it’s eight times as common among the dullest (IQ under 75) as it is among the brightest (IQ over 125). And males in the bottom half of the IQ distribution are nearly 10 times as likely as those in the top half to find themselves in jail. 14. Race gap: If the analysis stopped there, the findings probably wouldn’t excite much controversy. But Herrnstein and Murray pursue the same line of analysis into the painful realm of racial differences. Much of what they report is not new. It’s well Testing the Science of Intelligence / 5 160 165 170 175 180 185 190 195 established, if not well known, that average IQ scores differ markedly among racial groups. Blacks, like whites, span the whole spectrum of ability. But whereas whites average 102 points on the Wechsler test, blacks average 87. That gap has changed little in recent decades, despite the overall rise in both groups’ performances, and it is not simply an artifact of culturally biased tests. That issue was largely resolved 14 years ago by Berkeley psychologist Arthur Jensen. Jensen is still notorious for an article he wrote in 1969, arguing that the disappointing results of programs like Head Start were due partly to racial differences in IQ. His lectures were disrupted for years afterward, and his name became publicly synonymous with racism. But Jensen’s scientific output continued to shape the field. In a massive 1980 review titled “Bias in Mental Testing,” he showed that the questions on IQ tests provide equally reliable readings of blacks’ and whites’ abilities. He also showed that scores had the same predictive power for people of both races. In 1982, a panel assembled by the National Academy of Sciences reviewed the evidence and reached the same conclusion. 15. If the tests aren’t to blame, why does the gap persist? Social scientists still differ sharply on that question. Poverty is not an adequate explanation, for the black-white IQ gap is as wide among the prosperous as it is among the poor. Some scholars, like University of Michigan psychologist Richard Nisbett, argue that the disparity could simply reflect differences in the ways children are socialized. Writing in The New Republic this week, Nisbett cites a North Carolina study that found working-class more intent than blacks on preparing their children to read. In light of such social differences, he concludes, any talk of a genetic basis for the IQ gap is “utterly unfounded.” Jensen, by contrast, suspects a large genetic component. The gap between black and white performance is not restricted to literacy measures, he says. It’s evident even on such culturally neutral (but highly g-loaded) tasks as repeating number sequences backward or reacting quickly to a flashing light. 16. Jensen’s view, as it happens, is more mainstream than Nisbett’s. Roughly two thirds of those responding to the Snyderman survey identified themselves as liberals. Yet 53 percent agreed that the black-white gap involves genetic as well as environmental factors. Only 17 percent favored strictly environmental explanations. 17. Herrnstein and Murray say they’re less concerned with the causes of the IQ gap than they are with its arguable consequences. Are Black America’s social problems strictly the legacy of racism, they wonder, or do they also reflect differences in mental ability? To answer that question, Herrnstein and Murray chart out the overall blackwhite disparities in areas like education, income and crime. Then they perform the same exercise using only blacks and whites of equal IQ. Overall, blacks in the NLSY are less than half as likely as whites to have college degrees by the age of 29. Yet among blacks and whites with IQs of 114, there is no disparity at all. The results aren’t always so striking, but matching blacks and whites for IQ wipes out half or more of the disparities in poverty, welfare dependency and arrest rates. Testing the Science of Intelligence / 6 200 205 210 215 220 225 230 18. Social scientists traffic in correlations, and these are strong ones. Correlations are of course different from causes; low IQ does not cause crime or illegitimacy. While Herrnstein and Murray clearly understand that vital distinction, it’s easily lost in their torrent of numbers. There is no longer any question, however, that IQ tests measure something hugely important in life. It’s also clear that whatever mental ability is made of – dense neural circuitry, highly charged synapses or sheer brain mass – we didn’t all get equal shares. TEST YOURSELF Sample student test questions 1. Acorn is to seed as oak is to – A. shade B. forest C. branch D. elm E. tree 2. What comes next in this series? A A B 1 B B C 2 C C D 3 D? A. F B. 3 C. 4 D. D D. E 3. Choose the word that best completes this sentence: The little boy cried _________ he cut his knee. A. although B. because C. unless D. before E. until 4. The numbers in the box go together in a certain way. Choose the number that goes where you see the question mark. ___________________________ 8 9 10 7 8 9 6 7 ? ___________________________ A. 5 B. 6 C. 8 D. 10 E. 13 Testing the Science of Intelligence / 7 Answer in your own words. 1. 2. 3. Answer the following question in English. On what score – paragraph 1 – have IQ tests been condemned for the past twenty years? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the following question in English. What, according to the information provided in paragraph 1, is the essence of Herrnstein’s and Murray’s thesis? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the following question in English. What, according to paragraph 1, is mainstream science inclined to assume on the issue of IQ testing? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Complete the sentence below. 4. On the issue of IQ, the differences between the social scientists referred to in paragraph 2 on the one hand and Herrnstein and Murray are merely ______________ 5. Answer the following question in English. What rather uncontroversial finding – paragraph 3 – is supposed to have been made at the beginning of the 20th century? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ 6. Answer the following question in English. What percentage of the American population score below 85 and above 115? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ 7. Answer the following question in English. On what point – paragraph 7 – are most researchers inclined to agree? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Testing the Science of Intelligence / 8 Answer the question below in Hebrew. 8. In what sense is the information provided in paragraphs 9-10 discouraging from the educational point of view? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the question below in Hebrew. 9. Describe some of the disheartening findings – paragraphs 12-13 – provided by Herrnstein and Murray in their book The Bell Curve. Answer: _____________________________________________________________ 10. 11. Answer the following question in English. What made The Bell Curve – paragraph 14 – particularly controversial? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the following question in English. In what way – paragraphs 14-15 – could tests be discriminatory? (The answer could be inferred.) Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the question below in Hebrew. 12. How would Nisbett’s claims – paragraph 15 – refute Jensen’s theory? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ 13. Answer the following question in English. What, according to paragraph 16, is the prevailing view on the issue of IQ differences between Blacks and Whites? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Testing the Science of Intelligence / 9 14. Explain in Hebrew the difference between causes on the one hand and correlations – paragraph 18 – on the other hand? Answer: _____________________________________________________________