Department of Clinical Physics & Bio-engineering

advertisement

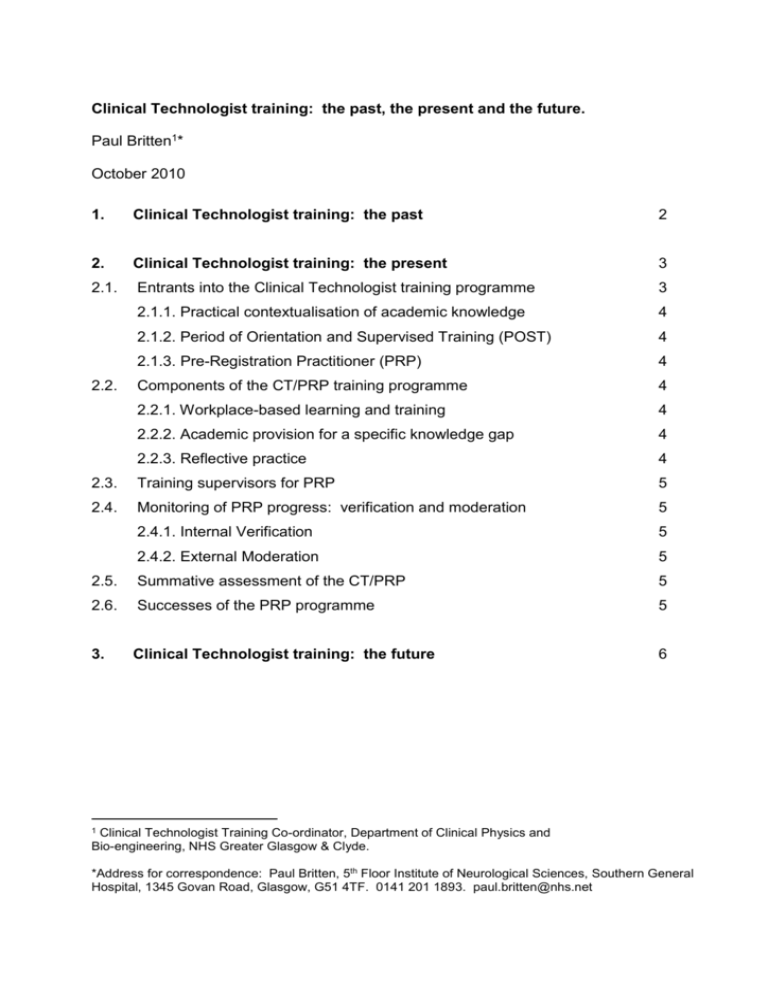

Clinical Technologist training: the past, the present and the future. Paul Britten1* October 2010 1. Clinical Technologist training: the past 2 2. Clinical Technologist training: the present 3 2.1. Entrants into the Clinical Technologist training programme 3 2.1.1. Practical contextualisation of academic knowledge 4 2.1.2. Period of Orientation and Supervised Training (POST) 4 2.1.3. Pre-Registration Practitioner (PRP) 4 Components of the CT/PRP training programme 4 2.2.1. Workplace-based learning and training 4 2.2.2. Academic provision for a specific knowledge gap 4 2.2.3. Reflective practice 4 2.3. Training supervisors for PRP 5 2.4. Monitoring of PRP progress: verification and moderation 5 2.4.1. Internal Verification 5 2.4.2. External Moderation 5 2.5. Summative assessment of the CT/PRP 5 2.6. Successes of the PRP programme 5 3. Clinical Technologist training: the future 6 2.2. 1 Clinical Technologist Training Co-ordinator, Department of Clinical Physics and Bio-engineering, NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde. *Address for correspondence: Paul Britten, 5th Floor Institute of Neurological Sciences, Southern General Hospital, 1345 Govan Road, Glasgow, G51 4TF. 0141 201 1893. paul.britten@nhs.net Clinical Technologist training: the past The Department of Clinical Physics and Bio-engineering (DCPB) has a credible track record in the provision of high quality training to produce competent Clinical Technologists in the areas of medical electronics, clinical instrumentation and equipment management. During the 1970s to the early 1990s, DCPB via the West of Scotland Health boards training consortium provided a supernumerary training programme for Student Medical Physics Technicians. Trainees followed an apprenticeship style programme for 5 years, combining workplace-based learning and day release study at a local Further Education College. Part-time study led to the award of formal academic qualifications (ONC in Applied Physics with Electronics and a HNC in Applied Physics with Instrumentation). Upon successful completion of the apprenticeship programme, trainees would be eligible to apply for substantive Medical Physics Technician posts in appropriate NHS Medical Physics departments if they so wished. The establishment of NHS trusts in from 1991 - 1998 led to the disbandment of the Student Medical Physics Technician supernumerary training programme. This was superseded by a vocational BSc Medical Physics Technology degree, which was developed and delivered by Glasgow Caledonian University from 1996 – 2001 and provided suitably qualified entrants into substantive Clinical Technology posts in the Medical Physics professions. However, due to the low numbers of entrants to the course and the demise of the Physics Department at Glasgow Caledonian University, another University partner was sought. Paisley University (now the University of the West of Scotland) developed an alternative vocational BSc (Hons) in Physics with Medical Technoloy. Unfortunately, the University of the West of Scotland course never received accreditation from Institute of Physics and Engineering in Medicine (IPEM). Accordingly, entry to the Voluntary Register for Clinical Technologists (VRCT) was difficult for individuals with this qualification and this, makes this course an unattractive route for entry into Clinical Technology. 2 1. Clinical Technologist training: the present There were two main drivers to the development and delivery of the current training programme for Clinical Technologists: the first was the formation of the VRCT (hosted by IPEM), an initiative to prepare Clinical Technologists for state registration; the second was the academic qualifications and practical experience of entrants to Clinical Technology posts in the absence of an appropriate vocational degree. The VRCT prospectus was used as the basis for the development of the Clinical Technologist training programme. The prospectus covers the scopes of practice that a trainee must demonstrate to achieve the award of the IPEM diploma for Clinical Technology; this also simultaneously allows entry onto the VRCT. 2.1. Entrants into the Clinical Technologist training programme At present, the supply of entrants into the Clinical Technology professions in Medical Physics and Bioengineering are drawn from two distinct categories; generally entrants have either: a relevant scientific or engineering degree, or relevant technical knowledge, experience and at least a technical HNC qualification or equivalent from other industries The Clinical Technologist training programme has been flexibly designed to accommodate the differences in academic knowledge versus practical experience of the entrants from the above two categories. 3 2.1.1. Pre-Registered Practitioners (PRPs) Clinical Technologist trainees are employed in substantive Clinical Technology posts. Clinical Technologist trainees are called Pre-Registered Practitioners (PRPs) and the training programme that they follow is the PRP training programme. 2.2. Components of the PRP training programme As PRPs are employed in substantive posts, delivery of the PRP training programme is, on the whole, workplace-based, with a small proportion of formal academic knowledge being delivered at a local Further Education College. Evidence of achievement of competency of the components of the PRP training programme is through a portfolio of evidence. The portfolio also includes reflective practice. 2.2.1. Workplace-based learning and training There are 36 areas of competency, which must be achieved by the PRP during their period of training. 2.2.2. Academic provision for a specific knowledge gap Many PRPs have a knowledge gap with regard to anatomy and physiology. This is met by NES funding the creation of a course delivered by a local FEI. 2.2.3. Reflective Practice Reflective practice is a record that demonstrates that the PRP is able to undertake a process of training/learning experiences. critical evaluation by reflecting on their Through reflection the PRP will be asking: what went well, what went wrong and as a result what they might do differently next time to improve their practice. 4 2.3. Training Supervisors for PRP The training supervisor appointed to the PRP is typically a DCPB section manager, although this does not have to be the case, as any senior Clinical Technologist within the section may be appointed as a training supervisor. new and existing PRP training supervisors attend a Train the Trainer and Assessor (TtTA) day, which was developed through NES, contextualised in the Physical Sciences. 2.4. Monitoring of PRP progress: verification and moderation The PRP progress is monitored internally and externally by: 1. an Internal Verifier; who is a senior Clinical Technologist within DCPB, but works in a different section to the CT/PRP. 2. an External Moderator on behalf of the IPEM. 2.5. Summative assessment of the PRP The summative assessment of the PRP comprises two parts: 1. the PRP training portfolio and reflective practice is summatively assessed by the IPEM External Moderator. The score awarded for the PRP portfolio and reflective practice is confirmed by the Support Moderator. 2. a final practical assessment and oral examination (viva), conducted by the IPEM External Moderator and second IPEM Support Moderator. 2.6. Successes of the PRP training programme The success of the PRP programme is measured by Clinical Technologists who been awarded the IPEM Diploma in Clinical Technology and gain entry to the VRCT. Since the inception of the PRP training programme in 2005, 10 PRPs have been awarded the IPEM diploma in Clinical Technology. 5 At present, there are 21 PRPs following the PRP training programme throughout the West of Scotland. 2. Clinical Technologist training: the future The appointment of a dedicated Clinical Technologist training co-ordinator for the West of Scotland (funded by NHS Education for Scotland (NES) for two years) provides an excellent opportunity to build upon the solid foundation that currently exists for Clinical Technologist training in the West of Scotland. It is proposed that the Clinical Technologist training co-ordinator will work, collaboratively and in partnership, on the following key areas of Clinical Technologist training: rationalisation of training resources delivered by DCPB. development of a core syllabus for the PRP training programme, for which aims and learning outcomes will be linked PRP competencies required for the award of the IPEM diploma in Clinical Technology. formal accreditation of the IPEM diploma to assign academic credit e.g. SCQF credit. facilitate the rolling out the PRP training programme into other branches of Clinical Technology and extension of the programme into other NHS territorial Health Boards where required. recruitment of new PRP training supervisors and educational development of existing training supervisors (see Train the Trainer Assessor day above). other key areas to be added as and when. In taking forward some of the above developments for Clinical Technologist training, it is important to be mindful of the current Scottish2 and UK3 policy for Healthcare Science, to ensure that the education and training for this group of Healthcare Science staff is relevant, fit for purpose and sustainable. 2 The Scottish Government. Safe, Accurate and Effective: An Action Plan for Healthcare Science in NHS Scotland. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government, 2007. 3 UK Health Departments. Modernising Scientific Careers: The UK Way Forward. London: The Department of Health, 2010 6