Diabetes in Long-Term-Care

advertisement

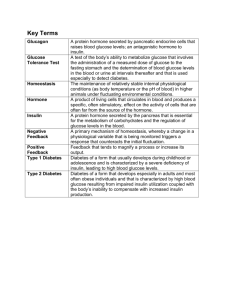

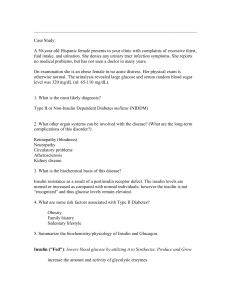

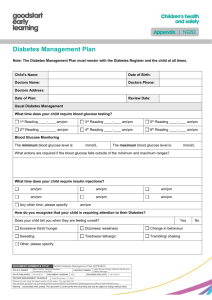

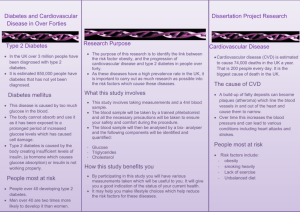

Diabetes in Long-Term-Care A summary of American Medical Directors Association (AMDA). Diabetes management in the long-term-care setting. Columbia, MD: American Medical Directors Association (AMDA); 2010. Assessment At the time of admission or during the preadmission process, the patient and his or her family members should be questioned regarding signs or symptoms of possible undiagnosed diabetes. Signs and symptoms, labs, and current or previously taken medications that are known to damage glucose metabolism or cause diabetes should be appraised. Remember that signs and symptoms of hyperglycemia may be atypical in frail, elderly individuals. Look for possible diabetes and complications as a part of the overall assessment during admission and required medical appointments, as well as at the request of the practitioner or if a sudden dramatic change occurs in the patient’s condition. If suspected, draw labs as soon as possible (either fasting or random). Correctly classify impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance as “prediabetes” (use the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes from the American Diabetes Association for criteria). Older adults in the early stages of diabetes often have normal fasting blood glucose (FBG) levels. If a patient has a normal fasting result, but has signs and symptoms of diabetes, complete a 75gram (g) oral tolerance test. All patients with impaired fasting glucose (IFG) or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) and other risks should have their FBG checked biannually. Patients on medication known to cause hyperglycemia should be considered for having FBG checked semiannually. Patient condition should be determined within one week of lab test. Base appraisal on available history, physical findings, additional medical records, and review of medications and labs. Order additional testing to confirm either diabetes or contributing disorders (eg, endocrinopathy, pancreatic disease, or adverse medication effects). Goal setting The glucose goals used for younger individuals can also often be used for the elderly. However, if there is a significant risk of adverse hypoglycemic events, use a goal as close to the general recommendation as possible. Within three weeks of admission or recognition of diabetes, team members with an active role in the care of the patient should see and assess functional, physical, and psychosocial impact of diabetes on the patient. Pertinent information must be provided so that staff and practitioners can summarize and consider appropriate interventions. Not all frail elderly individuals can attain the tight control recommended by the American Diabetes Association and the American Academy of Clinical Endocrinologists. Consider modifying blood glucose goals for: o Patients who are dependent for feeding or who have a generally poor prognosis o Patients with anorexia, gangrene, malignancy, or severe dementia o Life expectancy of less than five years If a patient is terminally ill or has a limited life expectancy, the provision of comfort and control of symptoms related to hyperglycemia is most appropriate, as long as it is properly documented why treatment is not being actively managed. Medical records and care planning At the next required medically necessary visit, and at all follow-up visits, scrutinize and document issues based on stability and disease burden, including: o Medical conditions and stability (blood glucose status and severity of complications) o The impact of diabetes on functioning and quality of life o Conditions that may be contributing to hyperglycemia o Reasons why other possible causes of diabetes are not pursued (frail, terminally ill, unwilling to undergo further intervention, etc) o Potential treatments for diabetes and other coexisting medical conditions o Reasons for recommending the use or nonuse of identified treatment options considering health status, advance directives, and personal wishes o Record when the patient was told that he or she has diabetes, was offered treatment options, and that interventions were agreed upon by the practitioner, patient, and family Practitioners and nurses develop a care plan for management of diabetes with input from other departments as appropriate. Patient goals and preferences must be included in the care plan. The patient and the family’s acceptance and participation in development of the care plan is critical. The care plan must contain: o Description of activity and physical therapy o Foot and wound care o Glucose monitoring o Meal plan o Pain management o Oral meds or insulin treatment o Short-term and long-term goals that address severity of disease, cardiovascular disease risk, and overall prognosis Handling acute problems Call practitioner immediately if: Blood glucose is 70 or less and patient is unresponsive, or consecutive readings of 70 or less are made If two or more readings are 250 or higher, or if accompanied by new medical problems or a change in conditional or functional status, and treatment has not already been initiated or modified If blood glucose is 300 or higher during all or part of two consecutive days (unless this represents an improvement or existing orders specify how to manage hyperglycemia for this specific patient) If the patient has not eaten or drunk sufficient fluids for two or more days and abdominal pain, fever, hypotension, lethargy or confusion, or respiratory distress are noted When there is a persistent pattern of poorly controlled or deteriorating blood glucose levels, notify the practitioner within 24 hours. Hypoglycemia Every facility should have a policy and procedure addressing the treatment of hypoglycemia. The following all increase the risk of hypoglycemia-related morbidity: o Nocturnal hypoglycemia o Cognitive and communication problems o Chronic heart or liver disease o Adrenal or pituitary deficiency o Immobility o Falls When considering using the rule of 15/15 (eat 15 g of carbohydrate and wait 15 minutes) to treat hypoglycemia, keep in mind that an individual might be unconscious or comatose or may be unable to receive glucose by mouth or tube. If this is the case, you will need to consider subcutaneous, intramuscular, or intravenous repletion. If episodes of hypoglycemia are frequent, the practitioner, along with the patient and family, should consider liberalizing glycemic control and adjust treatment. Medication and insulin Use a three tiered approach to glycemic management: o Metformin with lifestyle modifications as appropriate o Insulin or additional oral medication if metformin and lifestyle modification fail to achieve adequate control (or if metformin is contraindicated) o Initiate or intensify insulin when diet, exercise, and oral medication are not adequate (or if oral medications are contraindicated) Consider insulin for patients who either have type 1 diabetes or who have an A1c of >9% with symptoms of hyperglycemia or are uncontrolled on a combination of oral antidiabetics. When adding insulin to oral antidiabetics, use basal, pre- dinner mix, or intermediate-acting. For individuals with well-controlled diabetes and consistent eating habits, use a basal bolus regimen, a twice per day mixture, or a split-mixture of intermediate and short-acting insulin. Determine the appropriate insulin regimen and type based on the patient’s individual needs including weight, level of physical activity, and comorbid conditions. Use the estimated total daily dose to determine basal and bolus doses: o Calculate the total daily dose of insulin o Divide the total daily dose in half: 50% will be basal and 50% will be bolus o Space mealtime insulin at each meal to be 1/3 total daily bolus dose Basal analogs are better than NPH, because they carry a lower risk of hypoglycemia, can be given once daily in type 2 diabetes, and result in a similar reduction in FBG. Rapid-acting insulin is better than regular insulin, because it more closely mimics natural physiologic responses, has a more rapid onset and a shorter duration action, and results in a less severe hypoglycemic response. Note that metformin is not recommended for older long-term care patients with either chronic kidney disease or congestive heart failure. If the initial medication fails to improve glycemic control, consider combination treatment with different mechanical actions. Caregivers must rotate injection sites and use caution when mixing insulins. The previous rule of mixing clear insulin (regular, lispro, insulin aspart) before “cloudy” (intermediate) no longer applies and should not be used as instruction. Sliding scale insulin Sliding scale insulin therapy is not recommended for prolonged and routine use. It leads to an increased risk of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, is a reactive approach that can lead to rapid swings in blood glucose, and is likely to continue without proper modification when used as the admission regimen. The hazards clearly exceed the convenience. Sliding scale insulin should be reevaluated within one week and changed to a fixed daily insulin dose that minimizes the use of correction dosing. In one study, 54% of residents received sliding scale insulin at the time of insulin initiation and 83% remained on the regimen through the end of the study (6.4 + 6.1 months). Diet and weight Avoid dietary restriction; the term “diabetic diet” is outdated and is not recommended for the long-term care population. If weight loss is not feasible in an obese person, achieve and maintain blood glucose as closely as possible to normal and document this in the care plan. Try to increase physical activity, using a physical therapist or activity therapist, as much as possible. References and recommended readings American Medical Directors Association (AMDA). Diabetes management in the long term care setting. Columbia, MD: American Medical Directors Association (AMDA); 2010. Contributed by Elaine Hinzey, RDN, LD/N Review date: 12/29/15