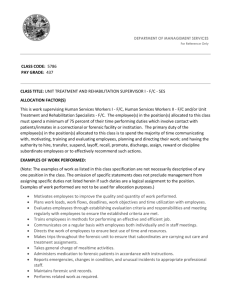

“Psychological Issues in Legal Contexts”

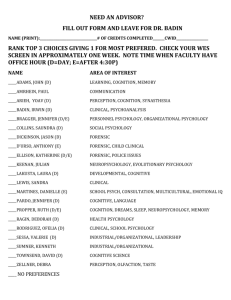

advertisement

“Psychological Issues in Legal Contexts” Proposal for Summer Elective Course Professor: Alissa Sherry, Ph.D.; Assistant Professor; Licensed Psychologist Proposed format of course: Workshop/seminar format meeting 5 Fridays first summer session from 8am to 5pm (with a 1 hour lunch break and two 15 minute breaks during the day). Course Goals: Expose professionals from multiple disciplines to the various psychological roles and influences in the courtroom. It is hoped that the multidisciplinary makeup of the class will contribute to this as students from a variety of programs are welcome to enroll such as counseling, school, clinical, and developmental psychology, social work, and the law school. Become familiar with case law as it relates to expert testimony, particularly as expert testimony applies to mental health professionals. Become familiar with ethical practices of forensic psychology. Exposure to psychological testing and assessment procedures used and considered “best practice” in various forensic contexts. A survey of mental health professional roles in the forensic context from civil to criminal issues. Proposed schedule: Day 1: Morning Introduction to case law allowing mental health professional testimony and outlining “expert” testimony Federal and State Rules of Evidence History and Systems perspective of mental health professionals involvement in legal proceedings: How did we get here and how do we stay here? Day 1: Afternoon Legal System Fundamentals o What types of courts hear what cases (Administrative law courts, District courts, courts of appeals, state supreme court, federal, etc) In what capacity do psychologists testify in the various courts o Criminal Cases: trial competence, Miranda rights waiver, transfers of juveniles to adult court, Mens rea issues as defenses (NGRI, etc), sentencing, probation and parole, capital cases, children as sworn v. unsworn witnesses, jury selection o Civil cases: malpractice (standard of care, proximate cause, damages and need for future treatment), personal injury, civil rights, competency (probate actions, contract actions, defamation actions), child custody Day 2: Morning The mental health professional as a forensic examiner o Clarification of role o Financial arrangements o Ethical issues—consent, competence, scope of practice o Data collection o Collateral interviews o Writing reports Day 2: Afternoon The mental health professional as an expert witness o Depositions o Mediation o Opposing counsel o Your demeanor o Preparing for testimony Day 3: Morning Psychological assessment as a part of the forensic evaluation o Standardized versus Unstandardized interview procedures o Objective assessment procedures (MMPI; MCMI; WAIS; WISC, etc) Day 3: Afternoon Psychological assessment as a part of the forensic evaluation o Use of projective assessment in forensic settings: limitations and advantages o Controversy over the use of the Rorschach Ink Blots o Kinetic Drawings, TAT o Conveying testing information to your audience: Judge, Jury, and Attorneys (report writing and verbal communication) Day 4: Morning The mental health expert in civil cases o Competency (guardianship; testamentary capacity; consent to research or treatment) o Family issues (child abuse and neglect; divorce, visitation, and custody; juvenile delinquency) o Personal injury and workmen’s compensation o Antidiscrimination and entitlement laws Day 4: Afternoon The mental health expert in criminal cases o Competency (to stand trial; to consent to search or seizure; to confess; to plead guilty; to waive right to counsel; to refuse insanity defense; to testify; to be sentenced and executed) o Mental state at time of offense (Not Guilty for Reason of Insanity (NGRI); exculpatory and mitigating circumstances o Sentencing o Jury Selection Day 5: Morning Starting a forensic practice o Marketing o Scope of practice o Fee agreements o Office policies Day 5: Afternoon Discussion panel o The current plan is to spend the afternoon with a panel of people who represent several areas of forensic process for a question and answer period of discussion with students: judges, attorneys, forensic psychologists, treatment practitioners who have been called to testify, etc. Evaluation procedures: Students will have two evaluative assignments. They are as follows: Assignment #1: There will be assigned readings each week. Students will be required to choose one reading per week to write a two-page reaction paper to this reading. These assignments are due weekly. Assignment #2: Students will have the option of choosing an area of forensic psychology in which they would like to specialize and write a 10 page paper on this area of psychology. This assignment is due at the end of the course. Representative Articles collected thus far (more to be added): Heilbrun, K., Warren, J., & Picarello, K. (in press). The use of third party information in forensic assessment. In I.B. Weiner and A. M. Goldstein (Eds.) Comprehensive Handbook of Psychology. American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (1997). Practice parameters for the forensic evaluation of children and adolescents who may have been physically or sexually abused. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 423-442. American Psychological Association, Committee on Professional Practice and Standards. (1999). Guidelines for psychological evaluations in child protection matters. American Psychologist, 54, 586-593. Association of Family and Conciliation Courts. (1994). Model standards of practice for child custody evaluation. Family and Conciliation Courts Review, 32, 504-513. Committee on Ethical Guidelines for Forensic Psychologists (1991). Specialty guidelines for forensic psychologists. Law and Human Behavior, 15, ?. Brodzinsky, D. M. (1993). On the use and misuse of psychological testing in child custody evaluations. Professional Psychology, 24, 213-219. Greenberg, S. A. & Shuman, D. W. (1997). Irreconcilable conflict between therapeutic and forensic roles. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 28, 1. Hess, A. K. (1998). Accepting forensic case referrals: Ethical and professional considerations. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 29, 109-114. Kirkland, K. & Kirkland, K. L. (2001). Frequency of child custody evaluation complaints and related disciplinary action: A survey of the association of state and provincial psychology boards. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 32, 171-174. Sales, B. D. & Simon, L. (1993). Special issue: The ethics of expert witnessing. Ethics & Behavior, 3. Shuman, D. W. Greenberg, S. Heilbrun, K., & Foote, W. E. (1998). An immodest proposal: Should treating mental health professionals be barred from testifying about their patients? Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 16, 509-523. Moskowitz, J. L., Lewis, R. J., Ito, M. S., & Ehrmentraut, J. (1999). MMPI-2 profiles of NGRI and civil patients. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 55, 659-668. Pope, J. & Meyer, R. (1999). An attributional analysis of jurors’ judgments in a criminal case: A preliminary investigation. Social Behavior and Personality, 27, 563-574. De la Fuente, L., De la Fuente, E. I., Garcia, J. (2003). Effects of pretrial juror bias, strength of evidence and deliberation process on juror decisions: New validity evidence of the juror bias scale scores. Psychology, Crime, & Law, 197-209. Weinborn, M., Orr, T., Woods, S. P., Conover, E., & Feix, J. (2003). A validation of Test of Memory Malingering in a forensic psychiatric setting. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 25, 979-990. DeClue, G. (2003). Toward a two-stage model for assessing adjudicative competence. The Journal of Psychiatry & Law, 31, 305-317.