Chronic kidney disease

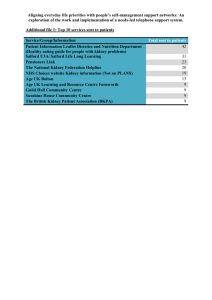

advertisement

Chronic kidney disease. Position paper 2007 Mai Rosenberg 1, Ruth Kalda 1, Vytautas Kasiulevičius 2 , Aivars Petersons 3, Margus Lember 1 1 University of Tartu, Estonia 2 University of Vilnius, Lithania 3 Stradins Medical Academy, Riga, Latvia Table of contents: Introduction Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a worldwide public health problem that is often under-diagnosed and under-treated. Definitions and classification Chronic kidney disease represents a progressive, irreversible decline in glomerular filtration rate (1). Most chronic nephropathies unfortunately lack a specific treatment and progress relentlessly to end stage renal disease. Progressive renal function loss is a common phenomenon in renal failure irrespectively of the underlying cause of the kidney disease (2). In recent years the concept of chronic kidney disease has gained more attention instead of chronic renal failure which is used to describe the more advanced stages of CKD. This is especially important for primary health care where the role of primary care providers is very important in handling the early phases of CKD to prevent or postpone chronic renal failure. In the current literature the terms CKD, renal insufficiency and renal failure are sometimes used without precisely defining these conditions. Chronic renal failure indicates to chronically (at least 3 months' duration) reduced kidney function (clearance, glomerular filtration rate [GFR]). Renal function declines normally with age, and exact level of decline at a given age that should be considered pathological is not known.The Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) statement considers GFR less than 60 mL/minute pathological at all ages. However, many elderly people have values less than this (in the USA, about 7% of white people without diabetes who are aged in their 60s and 15% of those aged in their 70s), and the extent to which low kidney function in the range of 30–60 mL/minute/1.73 m2 is pathological or progressive in all people is a subject of some controversy. Though people with end stage renal disease, by definition, have chronic failure of their kidneys (which may have resulted from an acute or a chronic process) they are generally not included in the term chronic renal failure, which in most of the literature and in this chapter refers exclusively to those with low kidney function who are not treated with renal replacement therapy. Chronic kidney disease defined by the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) statement as either the presence of abnormalities in urine or imaging that may lead to progressive disease or creatinine clearance (or glomerular filtration rate) less than 60 mL/minute/1.73 m2 . Chronic kidney disease includes chronic renal failure, but also includes predictors of chronic renal failure in people with normal kidney function (e.g. proteinuria), and end stage renal disease. The National Kidney Foundation - Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF-K/DOQI) workgroup has defined CKD as the following (10) which have been accepted internationally with some clarifications (7,11): The presence of markers of kidney damage for 3 months, as defined by structural or functional abnormalities of the kidney with or without decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR), that can lead to decreased GFR, manifest by either pathological abnormalities or other markers of kidney damage, including abnormalities in the composition of blood or urine, or abnormalities in imaging tests OR The presence of GFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for 3 months, with or without other signs of kidney damage as described above. Based upon representative samples of the United States population (12), the studies have estimated the prevalence of CKD in the general population through measurement of markers of kidney damage, such as elevated serum creatinine concentration, decreased predicted GFR, and presence of albuminuria. The term “albuminuria” should be substituted for terms “microalbuminuria” and “macroalbuminuria”. Increased urinary albumin excretion of albumin is the earliest manifestation of CKD due to diabetes, other glomerular diseases and hypertensive nephrosclerosis. Albuminuria may also accompany tubulointerstitial diaseases, polycysistic kidney disease, and kidney disease in transplant recipients (11). According to the KD:IGO position statement (11) the use of the term “disease” in CKD is consistent with: 1) the need for action to improve outcomes through prevention, detection, evaluation and treatment; 2) providing a message for public, physician and patient education programs; 3) common usage; and 4) its use in other conditions defined by findings and laboratory tests, such as hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia (11). Classification of CKD. CKD classified according to the severity, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis (11). Suffix “T” is used for all transplant recipients, at any level of GFR and, “D” for dialysis, for CKD stage 5 patients treated with dialysis. Clinical evaluation for CKD should include elucidation of the cause of disease. However, cause of the disease cannot be ascertained in all cases. Table Stage Description GFR (mL/min Related terms per 1.73 m2) Kidney damage ≥ 90 with normal or ↑ GFR Kidney damage 60-89 with mild ↓ GFR Moderate ↓ 30-59 GFR 1 2 3 4 Severe ↓ GFR 15-29 5 Kidney failure < 15 Albuminuria Proteinuria Hematuria Albuminuria Proteinuria Hematuria Chronic renal insufficiency Early renal insufficiency Chronic renal insufficiency Late renal insufficiency Pre-ESRD Renal failure Uremia End-stage renal disease “T” if kidney transplant recipient “D” if dialysis (HD, PD) References 1. Anderson, Brenner 2. Ots M, Pechter U, Tamm A: Characteristics of progressive renal disease. Clin Chim Acta 2000;2971-2:29-41. 3. Moeller S, Gioberge S, Brown G: ESRD patients in 2001: global overview of patients, treatment modalities and development trends. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002;1712:2071-2076. 4. Jager KJ, van Dijk PC. Has the rise in the incidence of renal replacement therapy in developed countries come to an end? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2007;22:678-680 5. U.S. Renal Data System, USRDS 2006 Annual Data Report: Atlas of EndStage Renal Disease in the United States, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD, 2006. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 47(Suppl 1):S1. 6. Locatelli F, D'Amico M, Cernevskis H, Dainys B, Miglinas M, Luman M, Ots M, Ritz E: The epidemiology of end-stage renal disease in the Baltic countries: an evolving picture. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2001;167:1338-1342. 7. Gregorio T Obrador, Brian JG Pereira. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease and screening recommendations. UpToDate 2007; 15 8. http://www.musili.fi/fin/munuaistautirekisteri/ 9. K. Kõlvald,…. Renal replacement therapy trends in Estonia. Transplant Int 2007: 10. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 2002; 39:S1.), 11. Levey, AS, Eckardt, KU, Tsukamoto, Y, et al. Definition and classification of chronic kidney disease: A position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int 2005; 67:2089. 12. Baigent C, Burbury K, Wheeler D: Premature cardiovascular disease in chronic renal failure. Lancet 2000;3569224:147-152. 13. Coresh, J, Astor, BC, Greene, T, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and decreased kidney function in the adult US population: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination survey. Am J Kidney Dis 2003; 41:1. 14. Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Sarnak MJ: Clinical epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis 1998;325 Suppl 3:S112119. 15. Pereira, BJG. Optimization of pre-ESRD care: The key to improved dialysis outcomes. Kidney Int 2000; 57:351. 16. Orth SR, Ritz E: The renal risks of smoking: an update. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2002;115:483-488. 17. Ritz E, Orth SR: Nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1999;34115:1127-1133. 18. Shlipak MG, Simon JA, Grady D, Lin F, Wenger NK, Furberg CD: Renal insufficiency and cardiovascular events in postmenopausal women with coronary heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;383:705-711. 19. Amann K, Tornig J, Kugel B, Gross ML, Tyralla K, El-Shakmak A, Szabo A, Ritz E: Hyperphosphatemia aggravates cardiac fibrosis and microvascular disease in experimental uremia. Kidney Int 2003;634:1296-1301. 20. Eknoyan G, Levey AS, Levin NW, Keane WF: The national epidemic of chronic kidney disease. What we know and what we can do. Postgrad Med 2001;1103:23-29: quiz 28 21. Meyer KB, Levey AS: Controlling the epidemic of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease: report from the National Kidney Foundation Task Force on cardiovascular disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 1998;912 Suppl:S31-42. 22. Holley, JL, Nespor, SL. Nephrologist-directed primary health care in chronic dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 1993; 21:628 23. Schwartz, JS, Lewis, CE, Clancy, C, et al. Internists' practice in health promotion and disease prevention: A survey. Ann Intern Med 1991; 114:46. 24. Zimmerman, DL, Selick, A, Singh, R, Mendelssohn, DC. Attitudes of Canadian nephrologists, family physicians and patients with kidney failure toward primary care delivery for chronic dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003; 18:305.) 25. Jean L Holley. The nephrologist as primary care physician in patients with end-stage renal disease. UpToDate 2007; 15 26. Inglismaal tehtud töö NDT, 2007 www.clinicalevidence.org Epidemiology and causes of CKD Very few of the causes of chronic renal failure are completely curable. It is often not necessary to do extensive tests to find a cause, however, for determining the stage and specific characteristics of the underlying disese follow-up of patients and thorough diagnostic work-up is needed. The three major groups of diseases leading to chronic kidney failure are diabetes, hypertension and renal diseases (mostly glomerulonephritides, tubulointerstitial nephritides and hereditary nephropathies, in particular autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease ADPKD). In different countries the proportions of these diseases as a cause of renal failure are different. However, in the western world the share of diabetes is steadily increasing. Out of the advanced or end-stage renal failure (Siegenthaler) in the UK diabetic nephropathy constitues 19%, hypertension 15%, chronic glomerulonephrits 10%, chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis 6%, ADPKD 6%. In the US diabetic nephropathy is the cause of chronic renal failuer even in 45%, hypertension in 27%, chronic glomerulonephritis in 11% of cases while chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis only in 3% and ADPKD in 2%. In Japan chronic glomerulonephritis is the main reason (47%), diabetic nephropathy 30%, hypertension 10%, chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis 2% and ADPKD in 2% of cases. Diabetes is one of the commonest causes of kidney failure in many countries (3,4,5). However, in Baltic countries diabetes epidemic has not been yet seen and patients with chronic glomerulonephritis usually form the main contingent of the end-stage renal disease (ESRD) population (6). In many countries there is a rising incidence and prevalence of kidney failure (3,4,5,6). Although the exact reasons for the growth of the ESRD patients are unknown, it is postulated that changes in the demographics of the population, differences in disease burden among racial groups and underrecognition of earlier stages of CKD and of risk factors for CKD, may partially explain this growth (7). However, recent trends show that the rate of increase of new cases of both diabetic and all-cause ESRD has progressively flattened in many countries (4,8) but this tendency is not universal and not seen in other populations (9). However, it is currently impossible to predict the long-term trend in the incidence rates of RRT in Europe. Therefore, secondary prevention should be organized as effective as possible at the population level. The prevalence and incidence of kidney failure treated by dialysis and transplantation in the United States have increased from 1988 to 2004. Whether there have been changes in the prevalence of earlier stages of chronic kidney disease (CKD) during this period is uncertain. The prevalence of CKD in the United States in 1999-2004 is higher than it was in 1988-1994. This increase is partly explained by the increasing prevalence of diabetes and hypertension and raises concerns about future increased incidence of kidney failure and other complications of CKD. / Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Levey AS. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:2038-47/ The prevalence of CKD in the US adult population was 11% (19.2 million). By stage, an estimated 5.9 million individuals (3.3%) had stage 1 (persistent albuminuria with a normal GFR), 5.3 million (3.0%) had stage 2 (persistent albuminuria with a GFR of 60 to 89 mL/min/1.73 m(2)), 7.6 million (4.3%) had stage 3 (GFR, 30 to 59 mL/min/1.73 m(2)), 400,000 individuals (0.2%) had stage 4 (GFR, 15 to 29 mL/min/1.73 m(2)), and 300,000 individuals (0.2%) had stage 5, or kidney failure. Aside from hypertension and diabetes, age is a key predictor of CKD, and 11% of individuals older than 65 years without hypertension or diabetes had stage 3 or worse CKD. / Coresh J, Astor BC, Greene T, Eknoyan G, Levey AS. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and decreased kidney function in the adult US population: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:1-12./ References: Siegenthaler W. Differential diagnosis in internal medicine. Thieme. Stuttgart New York 2007 1. Anderson, Brenner 2. Ots M, Pechter U, Tamm A: Characteristics of progressive renal disease. Clin Chim Acta 2000;2971-2:29-41. 3. Moeller S, Gioberge S, Brown G: ESRD patients in 2001: global overview of patients, treatment modalities and development trends. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002;1712:2071-2076. 4. Jager KJ, van Dijk PC. Has the rise in the incidence of renal replacement therapy in developed countries come to an end? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2007;22:678-680 5. U.S. Renal Data System, USRDS 2006 Annual Data Report: Atlas of EndStage Renal Disease in the United States, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD, 2006. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 47(Suppl 1):S1. 6. Locatelli F, D'Amico M, Cernevskis H, Dainys B, Miglinas M, Luman M, Ots M, Ritz E: The epidemiology of end-stage renal disease in the Baltic countries: an evolving picture. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2001;167:1338-1342. 7. Gregorio T Obrador, Brian JG Pereira. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease and screening recommendations. UpToDate 2007; 15 8. http://www.musili.fi/fin/munuaistautirekisteri/ 9. K. Kõlvald,…. Renal replacement therapy trends in Estonia. Transplant Int 2007: 10. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 2002; 39:S1.), 11. Levey, AS, Eckardt, KU, Tsukamoto, Y, et al. Definition and classification of chronic kidney disease: A position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int 2005; 67:2089. 12. Baigent C, Burbury K, Wheeler D: Premature cardiovascular disease in chronic renal failure. Lancet 2000;3569224:147-152. 13. Coresh, J, Astor, BC, Greene, T, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and decreased kidney function in the adult US population: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination survey. Am J Kidney Dis 2003; 41:1. 14. Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Sarnak MJ: Clinical epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis 1998;325 Suppl 3:S112119. 15. Pereira, BJG. Optimization of pre-ESRD care: The key to improved dialysis outcomes. Kidney Int 2000; 57:351. 16. Orth SR, Ritz E: The renal risks of smoking: an update. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2002;115:483-488. 17. Ritz E, Orth SR: Nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1999;34115:1127-1133. 18. Shlipak MG, Simon JA, Grady D, Lin F, Wenger NK, Furberg CD: Renal insufficiency and cardiovascular events in postmenopausal women with coronary heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;383:705-711. 19. Amann K, Tornig J, Kugel B, Gross ML, Tyralla K, El-Shakmak A, Szabo A, Ritz E: Hyperphosphatemia aggravates cardiac fibrosis and microvascular disease in experimental uremia. Kidney Int 2003;634:1296-1301. 20. Eknoyan G, Levey AS, Levin NW, Keane WF: The national epidemic of chronic kidney disease. What we know and what we can do. Postgrad Med 2001;1103:23-29: quiz 28 21. Meyer KB, Levey AS: Controlling the epidemic of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease: report from the National Kidney Foundation Task Force on cardiovascular disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 1998;912 Suppl:S31-42. 22. Holley, JL, Nespor, SL. Nephrologist-directed primary health care in chronic dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 1993; 21:628 23. Schwartz, JS, Lewis, CE, Clancy, C, et al. Internists' practice in health promotion and disease prevention: A survey. Ann Intern Med 1991; 114:46. 24. Zimmerman, DL, Selick, A, Singh, R, Mendelssohn, DC. Attitudes of Canadian nephrologists, family physicians and patients with kidney failure toward primary care delivery for chronic dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003; 18:305.) 25. Jean L Holley. The nephrologist as primary care physician in patients with end-stage renal disease. UpToDate 2007; 15 26. Inglismaal tehtud töö NDT, 2007 27. Screening Early treatment of chronic kidney disease and its complications may delay or prevent the development of end-stage renal disease, therefore detection of chronic kidney disease is believed to be a priority for primary care. (Snyder S, Pendergraph B 2005) There are reports suggesting that chronic kidney disease often is not detected, even when patients have access to primary care. (National Kidney Foundation. 2003; McClellan WM et al 2003) Which patients to screen? There is overwhelming consensus that screening for chronic renal disease should include high-risk groups. These include patients who have a family history of the disese, patients who have diabetes, hypertension, recurrent urinary tract infections, urinary obstruction or a systemic illness that affects the kidneys (National Kidney Foundation. 2002). Screening for asymptomatic persons beyond the above-mentioned patient groups has not found justification. The only exception are pregnant women: screening for bacteriuria is justified and its effect proven as the treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria has been found to be effective in benefit of newborns /US Task Force..../ How to screen? The most widely used methods for screening for kidney disease are an analysis of a random urine sample for albuminuria and a serum creatinine measurement to calculate an estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR). It is recommendable to use both of these methods as significant kidney disease can present with diminished GFR or proteinuria, or both. (Garg AX et al 2002) GFR is an indication of functioning kidney mass, the stages of chronic renal failure are based on an estimated GFR: Stage 1 GFR (ml per min per 1.73 m²) >89 Stage 2 60-89 Stage 3 30-59 Stage 4 15-29 Stage 5 <15 or dialysis Significant kidney dysfunction may be present despite a normal serum creatinine level. An estimated GFR based on serum creatinine level correlates better with direct measures of the GFR and detects more cases of chronic kidney disease than does the serum creatinine level alone. Clinically useful GFR estimates are calculated from the measured serum creatinine level after ajustments for age, sex and race. (Levey AS et al 1999; Cockcroft DW, Gault MH 1976) The two most commonly used formulas for GFR estimation are the MDRD (Modification of Diet in Renal Sisease) study equation and the CockcroftGault equation. Validation studies in middle-aged patients with chronic kidney disease showed MDRD study equation to be more accurate. (Levey AS et al 1999). However, the MDRD study equation was found to systematically underestimate the GFR in patients without chronic kidney disease.( Rule AD et al 2004) FORMULAS: Abbreviated MDRD study equation12† GFR (mL per minute per 1.73 m2) = 186 X (SCr)-1.154 X (age)-0.203 X (0.742, if female) X (1.210, if black) Cockcroft-Gault equation13 (140 - age) X weight CCr (mL per minute) = 72 X SCr X (0.85, if female) GFR = glomerular filtration rate; MDRD = Modification of Diet in Renal Disease; S Cr = serum creatinine concentration; CCr = creatinine clearance. *-For each equation, SCr is in milligrams per deciliter, age is in years, and weight is in kilograms. †-In validation studies,14-17 the MDRD study equation performed as well as versions with more variables; however, a recent study18 found that the equation underestimated the GFR in patients who did not have chronic kidney disease. C (mL per minute) =(140 - age) X weight X (0.85, if female) Cr 0,81 X SCr S Cr Micromol/L In most situations and as long as kidney function is stable, a calculated GFR can replace measurement of a 24-hour urine collection for creatinine clearance. Determination of creatinine clearance using 24-hour urine collection is still required in pregnant women, patients with extremes of age and weight, patients with malnutrition, patients with skeletal muscle diseases, paraplegia or quadripülegia, patients with a vegetarian diet and rapidly changuing kidney function. (Snyder S, Pendergraph B 2005) Detecting and quantitation of proteinuria are essential to the diagnosis and treatment of chronic kidney disease. Albumin, the predominant protein excreted by the kidney in most types of renal diseases, can be detected by urine dipstick testing. The proteincreatinine ratio in an early-morning random urine sample correlates well with 24-hour urine protein excretion and is much easier to obtain. (National Kidney Foundation 2002). Microalbuminuria often heralds the onset of diabetic nephropathy, therefore screening for microalbuminuria is recommended for all patients at risk for kidney disese. Screening can be performed using a microalbumin-sensitive dipstick or analysis of a random morning urine sample to determine the microalbumin-creatinine ratio. Screening for the diseases that may lead to chronic kidney failure. The most important reasons of chronic renal failure are diabetes and hypertension. Therefore early detection of these diseases and appropriate treatment is a method of avoiding or postponing complications, incl. chronic kidney failure. However, population-based screening for diabetes has not been found as an effective approache for improving diabetes outcomes. Screening of hypertension by measurement of blood pressure at the office visits has found support in many guidelines. Garg AX, Kiberd BA, Clark WF, Haynes RB, Clase CM. Albuminuria and renal insufficiency prevalence guides population screening: results from the NHANES III. Kidney Int 2002; 61:2165-75 Snyder S, Pendergraph B. Detection and evaluation of chronic kidney disease. Am Fam Physician 2005;72:1723-34 Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med 1999; 130:461-70. Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 1976; 16:31-41 National Kidney Foundation. KEEP: Kidney Early Evaluation Program. Annual data report. Program introduction. Am J Kidney Dis 2003; 42(5 suppl 4): S5-15; McClellan WM, Ramirez SP, Jurkovitz C. Screening for chronic kidney disease: unresolved issues. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003; 14 (7 suppl 2):S81-7. Rule AD, Larson TS, Bergstrahl EJ, Slezak JM, Jacobsen SJ, Cosio FG. Using serum creatinine to estimate glomerular filtration rate: accuracy in good health and in chronic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med 2004; 141:929-37 National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI, clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 2002; 39 (2 suppl 1): S1-266. US Task Force…. Prevention Main part of the total medical cost budget involves the treatment of CVD. Primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular and kidney disease remain the main purpose in modern medicine as cardiovascular morality represents the main reason of death in the world. The main cause of death in patients with CKD is cardiovascular catastrophe and the risk to die is in ESRD patients even 10-20 times higher compared with general population (13,14). Despite the magnitude of the resources committed to the treatment of ESRD and the substantial improvements in the quality of dialysis therapy, these patients continue to experience significant mortality and morbidity, and a reduced quality of life. Therefore, CKD should be recognized as early as possible and all prevention interventions that may arrest the kidney disease progression should be used. Earlier stages of CKD can be detected through laboratory testing, and that therapeutic interventions implemented early in the course of CKD are effective in slowing or preventing the progression toward kidney failure and its associated complications (15). When kidney disease progresses CKD patients become hypertensive, have acquired combined hyperlipidemia and hyperhomocysteinemia, increased oxidative stress, and decreased physical activity and psychosocial stress. If patients choose to smoke, the additive risk is profound (16). Diabetes mellitus is a major risk factor for both cardiovascular disease and CKD progression (17). Moreover, CKD patients are becoming older and are often menopausal if female (18). Finally, renal patients have a dramatic tendency for vascular and cardiac calcification that is related with hyperphosphatemia and secondary hyperparathyroidism (19). Also, the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases (CVD) in patients with CRF, especially in patients on renal replacement therapy, has shown to be 10-20 times greater than in the general population (14, 20). The management of several renal and CVD risk factors as hypertension, overweight, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and others should begin early in the course of chronic renal insufficiency with reno- and vasoprotective medications (21). In addition to classical risk factors such as age, male gender, smoking, hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidemia, physical inactivity, which also exist in the general population, patients with chronic renal failure have specific risk factors. Additional specific risk factors for advanced CKD are various uraemic toxines, hyperphosphatemia, severe prolonged oxidative stress, malnutrition, and hyperuricemia and immunosupressive treatment. Psychosocial factors, such as environmental stress and responsiveness to stress should not be unmentioned. The approach to the risk factors should be guided by the principle that chronic renal disease patients belong into the highest risk group for subsequent atherosclerotic complications. References 1. Anderson, Brenner 2. Ots M, Pechter U, Tamm A: Characteristics of progressive renal disease. Clin Chim Acta 2000;2971-2:29-41. 3. Moeller S, Gioberge S, Brown G: ESRD patients in 2001: global overview of patients, treatment modalities and development trends. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002;1712:2071-2076. 4. Jager KJ, van Dijk PC. Has the rise in the incidence of renal replacement therapy in developed countries come to an end? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2007;22:678-680 5. U.S. Renal Data System, USRDS 2006 Annual Data Report: Atlas of EndStage Renal Disease in the United States, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD, 2006. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 47(Suppl 1):S1. 6. Locatelli F, D'Amico M, Cernevskis H, Dainys B, Miglinas M, Luman M, Ots M, Ritz E: The epidemiology of end-stage renal disease in the Baltic countries: an evolving picture. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2001;167:1338-1342. 7. Gregorio T Obrador, Brian JG Pereira. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease and screening recommendations. UpToDate 2007; 15 8. http://www.musili.fi/fin/munuaistautirekisteri/ 9. K. Kõlvald,…. Renal replacement therapy trends in Estonia. Transplant Int 2007: 10. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 2002; 39:S1.), 11. Levey, AS, Eckardt, KU, Tsukamoto, Y, et al. Definition and classification of chronic kidney disease: A position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int 2005; 67:2089. 12. Baigent C, Burbury K, Wheeler D: Premature cardiovascular disease in chronic renal failure. Lancet 2000;3569224:147-152. 13. Coresh, J, Astor, BC, Greene, T, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and decreased kidney function in the adult US population: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination survey. Am J Kidney Dis 2003; 41:1. 14. Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Sarnak MJ: Clinical epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis 1998;325 Suppl 3:S112119. 15. Pereira, BJG. Optimization of pre-ESRD care: The key to improved dialysis outcomes. Kidney Int 2000; 57:351. 16. Orth SR, Ritz E: The renal risks of smoking: an update. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2002;115:483-488. 17. Ritz E, Orth SR: Nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1999;34115:1127-1133. 18. Shlipak MG, Simon JA, Grady D, Lin F, Wenger NK, Furberg CD: Renal insufficiency and cardiovascular events in postmenopausal women with coronary heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;383:705-711. 19. Amann K, Tornig J, Kugel B, Gross ML, Tyralla K, El-Shakmak A, Szabo A, Ritz E: Hyperphosphatemia aggravates cardiac fibrosis and microvascular disease in experimental uremia. Kidney Int 2003;634:1296-1301. 20. Eknoyan G, Levey AS, Levin NW, Keane WF: The national epidemic of chronic kidney disease. What we know and what we can do. Postgrad Med 2001;1103:23-29: quiz 28 21. Meyer KB, Levey AS: Controlling the epidemic of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease: report from the National Kidney Foundation Task Force on cardiovascular disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 1998;912 Suppl:S31-42. 22. Holley, JL, Nespor, SL. Nephrologist-directed primary health care in chronic dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 1993; 21:628 23. Schwartz, JS, Lewis, CE, Clancy, C, et al. Internists' practice in health promotion and disease prevention: A survey. Ann Intern Med 1991; 114:46. 24. Zimmerman, DL, Selick, A, Singh, R, Mendelssohn, DC. Attitudes of Canadian nephrologists, family physicians and patients with kidney failure toward primary care delivery for chronic dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003; 18:305.) 25. Jean L Holley. The nephrologist as primary care physician in patients with end-stage renal disease. UpToDate 2007; 15 26. Inglismaal tehtud töö NDT, 2007 Predialysis Renal replacement therapy- role of primary care , internists and nephrologists Availability of renal replacement therapy (RRT) forces the nephrologist to consider its application in every patient in whom it might be indicated. As kidney disease progresses patients cannot get help from family physician because of predialysis activities and preparations to RRT. Patients can feel even that the nephrologist is the only doctor who should manage all medical problems. Ideally, RRT is planned early and each patient and clinical setting judged individually. Usually, specific predialysis program takes several months and during this time CKD patients often visit dialysis center. There are many clinical problems in patients with CKD during predialysis and RRT period that can be associated with CKD but not always. Therefore, nephrologists often provide primary care or nonrenal related medical care to predialysis or to patients undergoing chronic haemodialysis because patient visits the center often. The nephrologist is the first who makes diagnose for instance of acute illness. Evidence shows that many patients do not have even family physician and patients often feel also that the nephrologist should manage their acute illness. On the other hand, comparison of HD and CAPD patients PD patients less depended upon their nephrologists (22). A paucity of objective data exists concerning the nephrologist's role as a primary care provider. Several studies suggest that the volume and type of practice provided by the nephrologist for patients with ESRD may be similar to that of the primary care practitioner (23,24,25). The problem is that if CKD patient numbers increases then in many places may be lack of nephrologists who have time and also experience to manage all medical problems in their RRT patients. It is probably true that patient outcome may be influenced by the expertise of the physician but no studies have been focused on the topic to compare outcome data of CKD populations managed only with specialist and both with specialist together with internist References 1. Anderson, Brenner 2. Ots M, Pechter U, Tamm A: Characteristics of progressive renal disease. Clin Chim Acta 2000;2971-2:29-41. 3. Moeller S, Gioberge S, Brown G: ESRD patients in 2001: global overview of patients, treatment modalities and development trends. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002;1712:2071-2076. 4. Jager KJ, van Dijk PC. Has the rise in the incidence of renal replacement therapy in developed countries come to an end? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2007;22:678-680 5. U.S. Renal Data System, USRDS 2006 Annual Data Report: Atlas of EndStage Renal Disease in the United States, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD, 2006. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 47(Suppl 1):S1. 6. Locatelli F, D'Amico M, Cernevskis H, Dainys B, Miglinas M, Luman M, Ots M, Ritz E: The epidemiology of end-stage renal disease in the Baltic countries: an evolving picture. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2001;167:13381342. 7. Gregorio T Obrador, Brian JG Pereira. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease and screening recommendations. UpToDate 2007; 15 8. http://www.musili.fi/fin/munuaistautirekisteri/ 9. K. Kõlvald,…. Renal replacement therapy trends in Estonia. Transplant Int 2007: 10. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 2002; 39:S1.), 11. Levey, AS, Eckardt, KU, Tsukamoto, Y, et al. Definition and classification of chronic kidney disease: A position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int 2005; 67:2089. 12. Baigent C, Burbury K, Wheeler D: Premature cardiovascular disease in chronic renal failure. Lancet 2000;3569224:147-152. 13. Coresh, J, Astor, BC, Greene, T, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and decreased kidney function in the adult US population: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination survey. Am J Kidney Dis 2003; 41:1. 14. Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Sarnak MJ: Clinical epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis 1998;325 Suppl 3:S112-119. 15. Pereira, BJG. Optimization of pre-ESRD care: The key to improved dialysis outcomes. Kidney Int 2000; 57:351. 16. Orth SR, Ritz E: The renal risks of smoking: an update. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2002;115:483-488. 17. Ritz E, Orth SR: Nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1999;34115:1127-1133. 18. Shlipak MG, Simon JA, Grady D, Lin F, Wenger NK, Furberg CD: Renal insufficiency and cardiovascular events in postmenopausal women with coronary heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;383:705-711. 19. Amann K, Tornig J, Kugel B, Gross ML, Tyralla K, El-Shakmak A, Szabo A, Ritz E: Hyperphosphatemia aggravates cardiac fibrosis and microvascular disease in experimental uremia. Kidney Int 2003;634:12961301. 20. Eknoyan G, Levey AS, Levin NW, Keane WF: The national epidemic of chronic kidney disease. What we know and what we can do. Postgrad Med 2001;1103:23-29: quiz 28 21. Meyer KB, Levey AS: Controlling the epidemic of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease: report from the National Kidney Foundation Task Force on cardiovascular disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 1998;912 Suppl:S3142. 22. Holley, JL, Nespor, SL. Nephrologist-directed primary health care in chronic dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 1993; 21:628 23. Schwartz, JS, Lewis, CE, Clancy, C, et al. Internists' practice in health promotion and disease prevention: A survey. Ann Intern Med 1991; 114:46. 24. Zimmerman, DL, Selick, A, Singh, R, Mendelssohn, DC. Attitudes of Canadian nephrologists, family physicians and patients with kidney failure toward primary care delivery for chronic dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003; 18:305.) 25. Jean L Holley. The nephrologist as primary care physician in patients with end-stage renal disease. UpToDate 2007; 15 26. Inglismaal tehtud töö NDT, 2007 Concomitant major health problems in CKD patients (infections, nutrition, anaemia) Infection The more common pathogenic viral infections in chronic kidney disease (CKD) are cytomegalovirus, HIV-1, hepatitis C virus and parvovirus B19. Infectious diseases are the second most common cause of death in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients. (1,2) Among a representative sample of the US population, hepatitis C is independently associated with albuminuria among adults over the age of 40; however, it does not seem to be significantly associated with a low eGFR in this populationbased cross-sectional analysis. (3) Hepatitis C also is a complicating factor among patients with end-stage renal disease and renal transplants. The source of HCV infection in these patients can be nosocomial. Screening and careful attention to infection control precautions are mandatory for dialysis units to prevent the spread of hepatitis C (12). Infection with parvovirus B19 causes several clinical syndromes (fifth disease, transient aplastic crisis, pure red cell aplasia, and hydrops fetalis) and may contribute to other illnesses. (4) Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients can develop different types of chronic kidney disease (CKD). The most common histological finding of renal biopsy is HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN). HIVAN is now the third most common cause of end stage renal failure (ESRF) (after diabetes mellitus and hypertension) in African-Americans aged 20–64 years. With the improved survival after the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in HIV-infected patients, there are increasing reports of development of CKD and ESRF in this population. (5) All patients at the time of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) diagnosis should be assessed for existing kidney disease with a screening urine analysis for proteinuria and a calculated estimate of renal function. Additional evaluations (including quantification of proteinuria, renal ultrasound, and potentially renal biopsy) and referral to a nephrologist are recommended for patients with proteinuria of grade >1+ by dipstick analysis or glomerular filtration rate (GFR) <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (6) Regardless of age and the presence of other comorbid illnesses, it is recommended that patients with chronic kidney disease receive regular vaccination. Hepatitis B is one of the most serious infectious diseases in the world. The virus can be transmitted among high-risk groups including CKD patients. HBV vaccination in patients with kidney disease remains highly recommendable. Hepatitis A virus vaccination among the general population has been used for decades. HAV vaccination in ESRD patients is well tolerated and immunogenic. Varicella may be severe and fatal infection in immunocompromised ESRD children. Varicella vaccination is safe and effective in ESRD patients and is thus recommended in these patients. Influenza is a common infection among CKD patients. Several studies showed that influenza vaccination was safe and effective in patients with CKD despite an impaired antibody response. In conclusion, influenza vaccination is highly recommended among ESRD patients. ESRD patients should thus receive Haemophilus influenza type B vaccine at the same doses as for healthy subjects. All children should be treated with measles, mumps and rubella vaccines (MMR), including dialysis patients. Diphtheria and tetanus infections can be prevented by using vaccines in ESRD patients. Pneumococcal vaccination is thus recommended in CKD patients with standard doses of 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine, but revaccination should be performed within 3–5 years. Live vaccines (yellow fever, polio, varicella and MMR vaccines) are generally avoided because they present a theoretical risk of vaccine-induced infection. (7) Infection after transplantation Infections remain the second most common cause of death in kidney transplant recipients. The risk for infection in these patients is determined primarily by the intensity of exposure to potential pathogens and the net state of immunosuppression. (8) Overall, the most prevalent opportunistic infections are viral, and CMV is the primary virus involved. CMV is the most common viral infection in the transplant population. CMV causes 2 major types of problems: direct effects, such as CMV syndrome and tissue invasive disease; and indirect effects, such as acute and chronic rejection, super-infections, cardiac complications, diabetes, and lymphoma. CMV infection and disease have been reported to be independent risk factors for acute renal allograft rejection. (9) Drugs that prevent CMV, either valacyclovir (10) or ganciclovir (11) or both, decrease the incidence of acute rejection. However, a host of community-acquired and opportunistic bacterial, viral, and fungal infections may occur at different rates depending on the period after transplantation. To reduce the burden of infection-related morbidity and mortality, patient vaccination status should be reviewed at the first clinic visit, and a vaccination strategy should be developed, keeping in mind that live vaccines are not given after transplantation and that patients, close contacts, and family members should receive injectable influenza vaccine yearly (inhaled influenza vaccine should not be given to transplant recipients or family members). Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine should be administered before transplantation and repeated every 3 to 5 yr after initial vaccination. Vaccination series should be restarted approximately 6 mo after transplantation, and efficacy should be documented by serologic assays when available. Finally, adult travelers after kidney transplantation need appropriate counseling and vaccinations before their tri). (8) References: 1. LeslieA.Bruggeman // Viral Subversion Mechanisms in Chronic Kidney Disease Pathogenesis // Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol., Jul 2007; 2: S13 - S19. 2. Foley RN. // Infections in patients with chronic kidney disease // Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2007 Sep;21(3):659-72. 3. Judith I. Tsui, Eric Vittinghoff, Michael G. Shlipak, and Ann M. O’Hare // Relationship between Hepatitis C and Chronic Kidney Disease: Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey // J. Am. Soc. Nephrol., Apr 2006; 17: 1168 - 1174. 4. Meryl Waldman and Jeffrey B. Kopp // Parvovirus B19 and the Kidney // Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol., Jul 2007; 2: S47 - S56. 5. Chi Yuen Cheung, Kim Ming Wong, Man Po Lee, Yan Lun Liu, Heidi Kwok, Rita Chung, Ka Foon Chau, Chung Ki Li, and Chun Sang Li // Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in Chinese HIV-infected patients // Nephrol. Dial. Transplant., Nov 2007; 22: 3186 - 3190. 6. Gupta SK, Eustace JA, Winston JA, Boydstun II, Ahuja TS, Rodriguez RA, Tashima KT, Roland M, Franceschini N, Palella FJ, Lennox JL, Klotman PE, Nachman SA, Hall SD, Szczech LA. Guidelines for the management of chronic kidney disease in HIV-infected patients: recommendations of the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2005 Jun 1;40(11):1559-85. 7. Nicolas Janus, Launay-Vincent Vacher, Svetlana Karie, Elena Ledneva, and Gilbert Deray // Vaccination and Chronic Kidney Disease// Nephrol. Dial. Transplant., Dec 2007; 10.1093/ndt/gfm851. 8. Arjang Djamali, Millie Samaniego, Brenda Muth, Rebecca Muehrer, R. Michael Hofmann, John Pirsch, Andrew Howard, Georges Mourad, and Bryan N. Becker // Medical Care of Kidney Transplant Recipients after the First Posttransplant Year // Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol., Jul 2006; 1: 623 - 640. 9. Sageda S, Nordal KP, Hartmann A, et al. The impact of cytomegalovirus infection and disease on rejection episodes in renal allograft recipients. Am J Transplant. 2002;2:850-856. 10. Lowance D, Neumayer HH, Legendre CM, et al. Valacyclovir for the prevention of cytomegalovirus disease after renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:14621470. 11. Ricart MJ, Malaise J, Moreno A, Crespo M, Fernandez-Cruz L. Cytomegalovirus: occurrence, severity, and effect on graft survival in simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20(suppl 2):ii25-ii32, ii62. 12. CM Meyers, LB Seeff, CO Stehman-Breen // Hepatitis C and renal disease: an update. // Am J Kidney Dis. 2003 Oct;42(4):631-57 Nutrition Dietary recommendation is important in management of CKD and the maintenance of broader health in CKD patients. Malnutrition is a frequent finding in ESRF, affecting 30-40% of patients. About 10% of patients on maintenance dialysis show signs of severe malnutrition. (1). Family physicians will be mostly efficient at the stage of malnutrition prevention, by implementing an early, interactive dietary and nutritional care programs in close collaboration with specialized dietitians. Extensive European (2,3) and US (4,11) guidelines on the assessment of nutrition in renal patients are available. All patients with stage 4-5 CKD should undergo regular nutritional screening. Nutritional assessment should include a minimum of a record of body weight prior to onset of ill health (well weight), current body weight and ideal body weight; body mass index (weight/height2); subjective global assessment, based on either a 3- or 7-point scale. Other measures of nutritional state are: serum creatinine, serum lipids, serum albumin and handgrip strength. If a patient has GFR < 30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, then his/her nutritional status should be monitored by measuring body weight and serum albumin every three months. (9) There is no single ‘gold standard’ measure of nutritional state. Therefore a panel of measurements should be used, reflecting the various aspects of protein-calorie nutrition. The dietary recommendations are different in all countries, but all guidelines agree that the energy intake in CKD patients is 35 kcal/kg/day and 30 kcal/kg/day may be sufficient in those over the age of 60. Sodium, total fat, cholesterol, carbohydrate, protein, phosphorus, potassium are restricted for CKD patients (1 table). Table 1. Macronutrient Composition and Mineral Content of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Diet Recommended by JNC 7, with Modification for Stages 3–4 of CKD (11) Nutrient Stage 1 – 2 of CKD Stage 3 – 4 of CKD Sodium (g/d)* < 2,4 < 2,4 Total fat (% of calories) < 30 < 30 Saturated fat (% of calories) < 10 < 10 Cholesterol (mg/d) < 200 < 200 Carbohydrate (% of calories)** 50 – 60 50 – 60 Protein (g/kg/d, % of calories) 1,4 (18) 0,6 – 0,8 (10) Phosphorus (g/d) 1,7 0,8 – 1,0 Potassium (g/d) >4 2-4 *Not recommended for patients with “salt-wasting” **Adjust so total calories from protein, fat and carbohydrate is 100 % The effects of dietary protein restriction are controversial. A meta-analysis in 1996 concluded that this intervention reduces proteinuria and slows the rate of the progression by reducing the rate of decline of GFR.(5) A later meta-analysis concluded that effects were less in RCTs than in non-RCT studies, that the effect was relatively greater in patients with diabetes, and that the magnitude of the effect was relatively weak. A Cochrane review, last updated in 1997 and not confined to RCTs, concluded that reducing protein intake does appear to slow progression of nephropathy in type 1 diabetes, but identified several unanswered questions: the level of protein restriction that should be used, whether compliance could be expected in routine care, and whether improvement in intermediate outcomes (eg creatinine clearance) would translate into improved clinical outcomes.(6) Since those reports an RCT confined to patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy has reported negative effects,(7) but an RCT in type 1 patients suggested a reduction in mortality.(8) Accordingly, the K/DOQI guidelines have recommended that CKD patients (GFR < 25 ml/min) receive a diet providing 0.6 g/kg of desirable body weight (DBW) per day of proteins (11), while others suggest that the protein content of the diet should not be lower than 0.75 g/kg/day, and should not exceed 0.8–1.0 g/kg/day (12– 16). Diets with <0.55 g/kg/day of proteins are strongly discouraged, for the risk of protein malnutrition (17). Some studies advocate that the reduction in protein intake below 0.8 g/kg/day in patients with advanced renal failure should be considered a criterion for starting dialysis therapy (16). Data of the last good quality study suggest that the 0.55 g/day diet guarantees a better metabolic control, as mirrored by the less frequent use of drugs, and it is not associated with a risk of malnutrition. (17) 1. D Fouque and F Guebre-Egziabher // An update on nutrition in chronic kidney disease. // Int Urol Nephrol, January 1, 2007; 39(1): 239-46. 2. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Care of Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease // UK Renal Association Clinical Practice Gudelines 4th Edition 2007 //www.renal.org/guidelines 3. Denis Fouque, Marianne Vennegoor, Piet Ter Wee // EBPG Guideline on Nutrition // Nephrol. Dial. Transplant., May 2007; 22: ii45 - ii87. 4. American Dietetic Association. Chronic kidney disease (non-dialysis) medical nutrition therapy protocol. Chicago (IL): American Dietetic Association; 2002 May. 5. Pedrini MT, Levey AS, Lau J, Chalmers TC, Wang PH. The effect of dietary protein restriction on the progression of diabetic and nondiabetic renal diseases: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 1996;124: 627–32. 6. Waugh NR, Robertson AM. Protein restriction for diabetic renal disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD002181. 7. Pijls LT, de Vries H, van Eijk JT, Donker AJ. Protein restriction, glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized trial. Eur J Clin Nutr 2002;56:1200–7. 8. Hansen HP, Tauber-Lassen E, Jensen BR, Parving HH. Effect of dietary protein restriction on prognosis in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 2002;62:220–8. 9. W. Kline Bolton // Renal Physicians Association Clinical Practice Guideline: Appropriate Patient Preparation For Renal Replacement Therapy: Guideline Number 3 // J Am Soc Nephrology, 14: 1406–1410, 2003 10. Chronic Kidney Disease 2006: A Guide to Select NKF-KDOQI Gudelines and Recommendation www.kidney.org/professionals/kls/pdf/Pharmacist_CPG.pdf 11. National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for nutrition in chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis (2000) 35:S56–S57. 12. CARI. Caring for Australian with Kidney Impairment. In: Chronic Kidney Disease. Nutrition and Growth in Kidney Disease Guidelines. http://www.cari.org.au/ckd_nutrition_list_updating.php. 13. Prichard S. Clinical Practice Guidelines of the Canadian Society of Nephrology for the treatment of patients with chronic renal failure: a reexamination. Contrib Nephrol (2003) 140:163–169. 14. Cianciaruso B, Barsotti G, Oldrizzi L, Gentile MG, Del Vecchio L. Italian Society of Nephrology. Conservative therapy Guidelines for chronic renal failure. G Ital Nefrol (2003) 20(Suppl 24):48–60. 15. The UK CKD Guidelines (2005) on the Renal Association website: http://www.renal.org/CKDguide/ckd.html. 16. Churchill DN, Blake PG, Jindal KK, Toffelmire EB, Goldstein MB. Guidelines for Treating Patients with CRF. Chapter 1: Clinical Practice Guidelines for Initiation of Dalysis. J Am Soc Nephrol (1999) 10:S287–S321. 17. Bruno Cianciaruso, Andrea Pota, Antonio Pisani, Serena Torraca, Roberta Annecchini, Patrizia Lombardi, Alfredo Capuano, Paola Nazzaro, Vincenzo Bellizzi, and Massimo Sabbatini // Metabolic effects of two low protein diets in chronic kidney disease stage 4–5—a randomized controlled trial // Nephrol. Dial. Transplant., doi:10.1093/ndt/gfm576 Anaemia Anemia is an early and common complication of chronic kidney disease. (1) The prevalence of anemia varies with the degree of renal impairment in predialysis patients with CKD, but once end-stage kidney failure occurs, all patients are eventually affected. In the NHANES III (the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) study (2), only 1% of participants with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) > 60 ml/min were found to suffer from anaemia [as defined in this study as a haemoglobin (Hb) concentration <12 g/dl in men or <11 g/dl in women]. However, in a cohort of patients with CKD, 25% of patients with a GFR >50 ml/min had Hb <12 g/dl (2). CKD patient categories with diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, diseases e.g. vasculitis, lupus erythematosus, advanced age, kidney transplantation are at high risk for anaemia development and should receive a greater level of attention. (3) According representative meta-analysis compared with Hb values of >130 g/L or more in the CKD population with cardiovascular disease, Hb values of <120 g/L were associated with lower all-cause mortality. Hb values of 100 g/L or less reduced the risk of hypertension, but increased the risk of seizures. From the available trial evidence, in CKD patients with cardiovascular disease, the benefits associated with higher Hb targets (reduced seizures) are outweighed by the harms (increased risk of hypertension and death). (4) Because anaemia is an early complication of CKD, patients with a GFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 should have their Hb level checked, and if found to be low then their anaemia should be further investigated and treated, as recommended by international guidelines (European Best Practice Guidelines (EBPG) or K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines) (5,7). Family physician role in assessment of anaemia should involve laboratory measurement of the following parameters: haemoglobin (Hb) concentration (to assess the degree of anaemia), mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and mean corpuscular Hb (MCH) (to assess the type of anaemia), absolute reticulocyte count (to assess erythropoietic activity), plasma/serum ferritin concentration (to assess iron stores), plasma/serum C-reactive protein (CRP) (to assess inflammation), assessment of occult gastrointestinal blood loss (to assess possibility of gastrointestinal bleeding). This is the basic patient evaluation and family physician usually can treat of most causes of anaemia. Fuller investigations can be done by specialist (hematologist or nephrologists). The Hb levels at which therapy with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) should be initiated, as well as its target Hb level, remain controversial (6). The EBPG recommend Hb values >11 g/dl (5), while the K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines and clinical practice recommendations suggest Hb levels between 11 and 13 g/dl (7). The use of a target hemoglobin level of 13.5 g per deciliter (as compared with 11.3 g per deciliter) was associated with increased risk and no incremental improvement in the quality of life.(8) Recent trials recommend a target Hb level between 11 and 12 g/dl in CKD patients. (8,9) 1. Kazmi WH, Kausz AT, Khan S, et al. Anemia: An Early Complication of Chronic Renal Insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis (2001) 38:803–812. 2. Hsu CY, McCulloch CE, Curhan GC. Epidemiology of anemia associated with chronic renal insufficiency among adults in the United States: results from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. J Am Soc Nephrol (2002) 13:504–510. 3. W. H. Hörl, Y. Vanrenterghem, P. Aljama, P. Brunet, R. Brunkhorst, L. Gesualdo, I. Macdougall, C. Wanner, and B. Wikström // OPTA: Optimal treatment of anaemia in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) // Nephrol. Dial. Transplant., June 2007; 22: iii20 - iii26 4. G. F.M. Strippoli, J. C. Craig, C. Manno, and F. P. Schena Hemoglobin Targets for the Anemia of Chronic Kidney Disease: A Metaanalysis of Randomized, Controlled Trials // J. Am. Soc. Nephrol., December 1, 2004; 15(12): 3154 - 3165. 5. Locatelli F, Aljama P, Barany P, et al. Revised European best practice guidelines for the management of anaemia in patients with chronic renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant (2004) 19(Suppl 2):ii1–47. 6. Remuzzi G, Ingelfinger JR. Correction of anaemia – payoffs and problems. N Engl J Med (2006) 355:2141–2146. 7. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines and clinical practice recommendations for anemia in chronic kidney disease in adults: Am J Kidney Dis. (2006) 47([Suppl 3]):S11–S145. 8. Singh AK, Szczech L, Tang KL, et al. Correction of anemia with epoetin alfa in chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med (2006) 16:2085–2098. 9. Drueke TB, Locatelli F, Clyne N, et al. Normalization of hemoglobin level in patients with chronic kidney disease and anemia. N Engl J Med (2006) 16:2071–2084. Education and guidelines Quality of care in CKD Shared care, referrals Recommendations, issues for policy makers Topics for discussion Best practice examples References Appendices