Exploring staff and students` mental maps: creating narratives for

advertisement

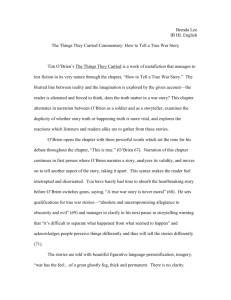

Exploring staff and students' mental maps: creating narratives for successful assessment feedback Rona O'Brien and Louise Sparshatt, Sheffield Hallam University Introduction The centrality of assessment to students' learning has been explored in detail in the literature (e.g. Gibbs and Simpson 2004/05) and within these discussions the role of feedback has been highlighted in terms of students' development (e.g. Brown 2004/05; Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick 2006). It has risen in importance on the national agenda since 2005, when the results of the first National Student Survey (NSS) were published and it was recognised that feedback was the area of greatest dissatisfaction for students across the sector. This has led to increased investigation of how assessment feedback can be used effectively (e.g. Huxham, 2007) and a number of institutions have reacted by investigating what students expect of their feedback and how they react to it (e.g. Nesbit and Burton, 2006; Poulos and Mahoney, 2007). This paper continues and develops work at Sheffield Hallam University (O'Brien and Sparshatt, 2007). The previous paper examined staff perceptions of their assessment feedback in relation to their ideas of how students perceive that same practice, as it was thought useful to understand academic ideas of practice so that engagement with feedback policies could be more effectively developed. This paper further explores the importance of these perceptions, or mental mind maps, to enable understanding of what underpins staff and students' beliefs about each other's assessment feedback practice. Staff interviews were carried out to enrich the findings of the first paper, and a survey and interviews with students sought to understand how students perceive assessment feedback and their perceptions of staff practice. The authors propose that while institutions tend to address issues of assessment feedback by taking a managerial approach, seeking to improve staff understanding of good feedback practice and managing student expectations, the solution, if there is one, is likely to be more complex as feedback practice is not altogether a rational process. Institutions may instead need to foster an ongoing dialogue between staff and students to create a shared understanding of what constitutes good assessment feedback practice and engender trust and knowledge of each other. To this end, it might be useful to compare academic and student mental maps of assessment feedback, as if academics and students are not aware of each others' expectations of assessment feedback and how they compare to their own, it may be difficult for them to engage in meaningful dialogue leading to effective changes in practice. Methodology The study began with a questionnaire of staff of differing levels of seniority and experience, asking them about their feedback practice and their perception of students’ expectations of summative (which may be formative in respect of the next piece of assessed work) assessment feedback. The questionnaire was sent to seven subject groups selected to give a range of different practices and different typical students (e.g. one subject teaches only professional mature students). The initial results were explored in O'Brien and Sparshatt 2007. Following this paper, the authors sought to enrich the results by holding a series of follow-up interviews with approximately a quarter of the staff who responded to the questionnaire, so that the results could be more grounded in the reality of staff’s assessment practice. The reality of students' feedback experience was explored by adapting the staff O'Brien and Sparshatt, 'Exploring staff and students' mental maps: creating narratives for successful assessment feedback', 1 July 2008 1 questionnaire for students, asking what they think is important in feedback, what they believe their tutors think, and their opinions of elements of feedback practice that previous studies have shown students find important. There were a number of follow-up focus groups and interviews; this aspect of the research will be developed to explore the implications of the findings further with students. Findings A comparison of the questionnaire results from staff and students on the same issues was undertaken to discover where the gaps in perception lie, and unpick the real issues that result in high or low student satisfaction with assessment feedback (see appendix). Possible reasons for these results are discussed below, informed by conversations with staff and students, using an expectations gap model to map perceptions of assessment feedback (Fig. 1, a modified form of the model used in O'Brien and Sparshatt, 2007). Each issue will sit in at least two boxes, firstly showing the outcomes of the comparison of perceptions, and secondly taking actual practice into consideration. Staff and Students agree Staff and students do not agree Perception Similarities /Conflicts 1 Students' expectations of staff's ideas of feedback practice match staff's ideas of students’ expectations 3 Students' expectations of staff's ideas of feedback practice do not match staff's ideas of students’ expectations Staff Practice in Comparison with Student Expectations 2 Staff's actual practice does not match students' expectations 4 Staff's actual practice matches students' expectations Figure 1: Expectations Gap Model (O'Brien and Sparshatt) The ideal is that staff and students' ideas about each other's perception of feedback practice match, and actual practice matches students’ expectations, a combination of Boxes 1 and 4. However, the presence of results in these boxes is not always positive; although student dissatisfaction and staff frustration tend to arise where there is a gap between expectations and practice, there may also be situations where boxes 1 and 4 are relevant but students have learnt to survive poor feedback practice (Pitts, 2005, p. 227). Expectations on both sides are low and practice lives up to them: "each tutors’ reference style is different you get used to it, but sometimes you don’t remember to change it" (student comment). If Boxes 1 and 2 are relevant there can be considerable frustration on the part of students who do not understand why practice does not live up to their expectations and, superficially, there is no reason why it should not. "Why can’t they tell us when we will get our assignments back?" (Student comment). Such a situation may indicate serious problems with institutional systems and processes. It may also suggest that though staff and students appear to agree, staff do not think that students are correct in their perception of good practice (see discussion of the ‘mark’ below). O'Brien and Sparshatt, 'Exploring staff and students' mental maps: creating narratives for successful assessment feedback', 1 July 2008 2 If Boxes 3 and 4 are relevant, students will be reasonably satisfied with practice, but staff may be frustrated: "if feedback tells them how they can develop, students don't care as long as they have passed" (staff comment). Staff may feel demotivated and cynical. If Boxes 3 and 2 are relevant staff may be less frustrated as their practice is consistent with their perception of what students want: "students receive a feedback matrix; it is hard for them to get used to, but they accept it after a while" (staff comment), but students may be frustrated by what they feel is a lack of understanding of their needs by staff. In summary, Boxes 1 and 4 signal that there will be little staff and student frustration and dissatisfaction with feedback practice, but other combinations: 1 and 2, 3 and 4 and, 3 and 2 produce frustration and dissatisfaction on the part of staff and/or students. Some of the main findings are discussed below with reference to the model. Is the mark the main purpose of feedback? Staff strongly believed that the mark is what students are interested in, often to the exclusion of anything else, and are frustrated by this mechanistic approach to learning: "students focus on the mark: how to get a good mark" (staff comment) (Fig. 2). Students think staff realise that the mark is not useful on its own (Box 3). For students, the mark and supporting feedback are interdependent; a mark alone is insufficient, even if returned quickly, and feedback without a mark is not useful. As one student put it, 'the mark gives the context for the feedback'. In other words, students need the feedback in order to be able to understand the mark, and the mark to be able to understand the emphasis they should put on the feedback. Staff may believe students overly prioritise the mark because assignments are often handed back in the classroom where they observe the students’ immediate, and natural, interest in their mark. What staff do not see is students' interest in the more detailed feedback when they have left the classroom. This situation has caused some staff to return feedback without the mark, to ensure that students make better use of feedback without this distraction (Boxes 3 and 2). Mark is most important part of feedback 80 70 60 50 Mark is most important part of feedback 40 30 20 10 0 Staff agree Staff think students agree Students agree Students think staff agree Figure 2: Views on the importance of the mark Rather than attempting to ‘trick’ students (i.e. manage expectations) into using the feedback, it is proposed that staff should work with students' need to contextualise feedback with the mark (Smith and Gorard, 2005): hand them back together and allow O'Brien and Sparshatt, 'Exploring staff and students' mental maps: creating narratives for successful assessment feedback', 1 July 2008 3 students time to deal with the emotional impact of the mark and then take in the developmental aspects of the feedback (which discussions with students show is the natural process for engaging with the feedback), i.e. move from box 2 to 4. This seems to be particularly relevant as even staff who engage in this practice admit that students "get cross, because they don’t get their marks back until after the oral feedback" (staff comment). The purpose of feedback is to suggest improvements for future work. Staff clearly believed this, but did not believe students agreed. Discussions with staff elicited that many believe students are unable to make connections between modules, or are mechanistic in their approach to assessment: "they move on after completion – students see it in stages of hurdles" (staff comment), Staff’s unwillingness, strongly put at times, to believe that students use or want to use feedback for future learning ("they just want to get across the barrier of passing" - staff comment) may be directly linked to ideas about students’ prioritisation of marks (see above). Students appear to believe that staff think this is an important purpose of feedback, but not as wholeheartedly as staff believe it themselves (Box 3). This may reflect the type of feedback that students feel they receive; if it is concerned primarily with specific subject content (Boxes 3 and 2), students will think staff do not believe in the future applicability of feedback. Staff recognise this problem ("modules are content driven, the importance for students’ learning processes is not valued" - staff comment), but some feel that "strong leadership and more flexibility of resources at the module level is required to develop more useful feedback" (staff comment). It is important that feedback is returned as soon as possible after the assessment. Staff correctly believe that this is very important to students, as borne out by the literature (e.g. Lea and Street, 1998). However, students incorrectly believe that staff think it is unimportant to students (see Figure 3), due in a large part to actual practice (Boxes 3 and 2). It is important to return w ork as soon as possible 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 It is important to return w ork as soon as possible Staff agree Staff think students agree Students agree Students think staff agree Figure 3: Importance of speed of return of work Discussions with students showed that, in reality, students do think staff know they value the speedy return of feedback (Box 1) but actual practice does not match expectations (Box 2), and their feelings of frustration override rational thinking about staff practice. Some students recognise the problems staff face in returning feedback quickly, e.g. workloads, but their constantly disappointed expectations mean they express negative views in surveys such as the NSS because they feel staff do not care about them. This O'Brien and Sparshatt, 'Exploring staff and students' mental maps: creating narratives for successful assessment feedback', 1 July 2008 4 highlights the need to address the practical process and system issues that often affect feedback, rather than overly concentrating on developing academic staff practice. It is important that students are motivated to use the feedback. Staff believe very strongly that students should be motivated to use the feedback, but do not believe that students realise this. Just over half of student responses said they understand that they have to be motivated to get the most out of their feedback but feel that staff do not recognise this in them (Box 3). Students believe that staff do not think students need to be motivated to use the feedback. It is interesting to reflect on how this misperception could have emerged for students, as staff strongly believe in the need for student motivation and feel frustrated by a perceived lack of it. A number of hypotheses for further investigation with students emerge, such as whether staff negativity about the autonomy of students with respect to their learning is transmitted to students ("students are passive, they have to be directed" - staff comment), whether students see the handout culture as a sign that staff believe they do not need to be motivated, but the handout culture simultaneously makes students appear passive to staff, or whether it could be an effect of large cohorts and the resulting lack of a close relationship between staff and students. Despite staff's belief that students make little use of feedback, the majority of staff provide good feedback (Boxes 3 and 4): "feedback is important; I would not feel comfortable just giving back a mark" (staff comment). It is important that the feedback is detailed. Staff accurately say that students want detailed feedback, the importance of which they recognise themselves. However, students do not feel that staff see this as important (Box 3). Staff would on the whole judge that they give detailed feedback to students, though most admit that feedback is less detailed for students gaining good marks: "as there is little to say", "it save times" (staff comments). However, students appear to have a different view of what constitutes detailed feedback. For example, feedback from students has shown that they appreciate personalised feedback, rather than generic. Therefore a detailed piece of generic feedback to the whole class, or a detailed matrix given to each student may be ignored. It is possible that for students 'detailed' means personalised, while to staff it means extensive. The response to this issue is often to explain to students what feedback is, but explaining to an everchanging population of students what staff consider to be feedback may be a Canute-like attempt to turn back the tide. As students are clear about the feedback they find useful, perhaps management efforts should concentrate on finding ways to support staff with the resources and time to produce personalised feedback that students will then recognise as 'detailed.' It is important that an appropriate amount of praise is contained in the feedback. Both staff and students believe it is important but neither believes that the other feels it is important (Box 3). Discussions with staff elicited a view of students that was onedimensional and mechanistic: "students do not have a need for learning, it is just business" (staff comment). A student who was truly focussed in this manner would therefore not care about praise. Students do not believe staff feel it is important to include praise, though staff do provide praise (Boxes 3 and 4). Does this reflect the feedback they receive, or could it be that they find the praise difficult to extract because the feedback is not clear? As Lizzio and Wilson (2008, p.264) point out 'Students can recognize and discount token or formulaic positive O'Brien and Sparshatt, 'Exploring staff and students' mental maps: creating narratives for successful assessment feedback', 1 July 2008 5 comments'. Most staff believe, and state they put into practice, that negative and positive points should be balanced, but could the effect be to mask the positive because of the disproportionate emotional impact of the negative points? This will be discussed further with students. An appropriate amount of praise should be included 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 An appropriate amount of praise should be included Staff agree Staff think students agree Students agree Students think staff agree Figure 4: An appropriate amount of praise should be included in the feedback There were also interesting differences between staff and student views of each others' perspectives concerning use of feedback for revision and opportunities for discussion with staff. Both of these areas require further investigation with students to determine their understanding of the issues. Conclusions The importance of feedback to students' learning has been demonstrated by the literature, and was confirmed by staff and students during this research, but the research highlights major gaps in staff and students perceptions of each other. It was striking that when the results of the two questionnaires were compared, students often assumed that issues were unimportant for staff that staff considered very important, because staff did not deliver feedback to students in a way they value. These gaps lead to frustration and dissatisfaction for staff and students, and contribute greatly to the negative picture they often have of each other. A number of practical issues emerged from students' feedback that have a disproportionate impact on students' ability to make effective use of feedback, e.g. illegible handwriting, poor timeliness, inconsistency of approach, (e.g. referencing). These issues are familiar, but it is proposed that the emphasis of an institution's feedback improvement work should firstly focus on these issues rather than informing staff about good practice, especially in the light of previous research (O'Brien and Sparshatt 2007) which showed staff were generally clear about the attributes of good practice. If such issues are not addressed, attempts to improve the quality of feedback are meaningless as the ‘noise’ in the system distorts the students’ view of the quality of the feedback. For staff, the practical issues are processes that they recognise but do not prioritise, or for which systems do not allow prioritisation. The academic task of providing detailed feedback to improve students' learning will take precedence over, for instance, quick return of work, and informing students of feedback deadlines is ‘nice’ but not essential. However, students who have to work to stated deadlines may feel aggrieved that staff do not, in their opinion, play fair: "Feel often 'fobbed off' as to why feedback is not given promptly…Just a lack of common courtesy really!" (Student comment). Students may feel this reflects their low status in staff’s perception. O'Brien and Sparshatt, 'Exploring staff and students' mental maps: creating narratives for successful assessment feedback', 1 July 2008 6 A number of staff questionnaires noted that it is hard to generalise about students as they are individuals. However, in-depth conversations with staff showed that most staff do tend to generalise about their students as excessively mark-oriented and passive, which is reinforced when, for instance, students do not come to see them to discuss their work. This perception perhaps indicates a lack of understanding of the power relationship between staff and students. It could also mean that students find feedback difficult to engage with either due to the methods used, "I don’t read a lot and pay more attention to oral feedback" (student comment), or because they feel embarrassed by failure. Staff may underestimate the impact of staff actions on students' confidence and motivation. For example, the inconsistency of practice in return of feedback has a cumulative effect on students, increasing the pressure they are under and reducing their trust in staff and the institution. Students, too, can generalise about staff, but generally have a good understanding of the pressures staff are under and that the majority are trying to do a good job: "I understand that tutors have to give feedback on several pieces of work as there are lots of students taking the course and presume this is why our feedback takes a while" (student comment). These are just some outcomes of the research and a number of elements need further investigation and analysis. However, it is generally acknowledged that the sector has struggled to implement good assessment feedback for the majority of students; this paper proposes that this may be partly due to an over-concentration on the promotion of what appears, to staff, to be inappropriate student-led practice without an informed discussion between staff and students as to what is good practice for both parties, not just students. Staff who feel powerless when presented with a context in which the student is a customer and the customer is always right, may become defensive. They will suggest that students do not appreciate ‘what is good for them', that they need to be educated about good feedback practice and their expectations managed and/or challenged. Students, on the other hand, may be frustrated by ineffective systems and/or staff’s inability, as they see it, to understand their needs and see that they want their expectations met, not managed. A way forward may lie in taking a less managerial view of how to create successful feedback, to develop an ongoing narrative between staff and students where each party discovers each other's values, views and practice, and a dialogue is created in which the nature of feedback and what makes it 'good' can be usefully explored. Rona O'Brien (r.m.obrien@shu.ac.uk) Louise Sparshatt (l.sparshatt@shu.ac.uk) Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the staff of the Hallam Union, in particular Jen Hart and Nicky Harris, for facilitating the questionnaire for students. References Brown, S. (2004-05) 'Assessment for Learning', Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, Issue 1, 81-89 O'Brien and Sparshatt, 'Exploring staff and students' mental maps: creating narratives for successful assessment feedback', 1 July 2008 7 Gibbs, G. and Simpson, C. (2004-05) 'Conditions under which Assessment Supports Students' Learning', Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, Issue 1, 3-31 Huxham, M. (2007) 'Fast and Effective Feedback: are model answers the answer?' Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 32:6, 601-611 Lea, M R and Street, B V (1998) 'Student writing in Higher Education: An Academic Literacies Approach', Studies in Higher Education 23:2, 157-172 Lizzio, A. and Wilson, K. (2008) 'Feedback on assessment: students' perceptions of quality and effectiveness', Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33:3, 263-275 Nesbit, P. and Burton, S. (2006) 'Student Justice Perceptions following assignment feedback', Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 31:6, 655-670 Nicol, D. J. & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006), 'Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice', Studies in Higher Education, 31:2, 199-218 O'Brien, R. and Sparshatt, L. (2007) 'Mind the gap! Staff perceptions of student perceptions of assessment feedback', Higher Education Academy 2007 Annual Conference papers, D7, http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/events/conference/papers Orsmond, P., Merry, S. & Reiling, K. (2005) Biology students' utilization of tutors' formative feedback: a qualitative interview study', Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 30:4, 369-386 Pitts, S. E. (2005), 'Testing, testing...: How do students use written feedback?', Active Learning in Higher Education, 6:3, 218-229 Poulos, A. and Mahoney, M. (2007) 'Effectiveness of Feedback: the Students' Perspective', Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33:2, 143-154 Smith, E. and Gorard, S. (2005) '"They don't give us our marks": the role of formative feedback in student progress', Assessment in Education, 12:1, 21-38 O'Brien and Sparshatt, 'Exploring staff and students' mental maps: creating narratives for successful assessment feedback', 1 July 2008 8 Appendix: Differences between staff and students perceptions of assessment feedback – Results STATEMENT Staff Agree Students Students believe agree Staff agree 20.9% 25.6% Staff believe students agree 70% The main purpose of feedback is to deliver a mark to the student. 27% Primarily, the purpose of feedback is to suggest changes/improvements to increase students' learning to aid the next piece of assessment in any module. 85% 51.2% 69.8% 30% 60% 9.3% 58% 82% 91% 30.2% 51.2% 16% 77% 20.9% 62.8% 57% It is important that an appropriate amount of praise is contained in the feedback, as well as just issues and corrections. 77% 12% 40% 24% It is important that the feedback is useful for revision purposes. 30% 14% 40% 32% It is important that students have an opportunity to discuss the feedback with staff 55% 12% 35% 39% It is important that feedback is returned as soon as possible after the assessment. It is important that students are selfmotivated to make the most of the feedback provided. It is important that the feedback is detailed (suggest changes and improvements and points out errors). O'Brien and Sparshatt, 'Exploring staff and students' mental maps: creating narratives for successful assessment feedback', 1 July 2008 9