Brenda Lee - ibenglish2011

advertisement

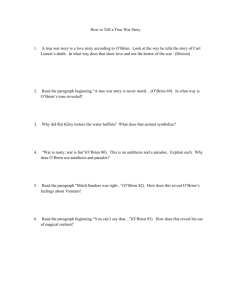

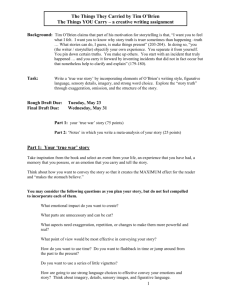

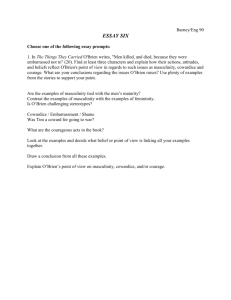

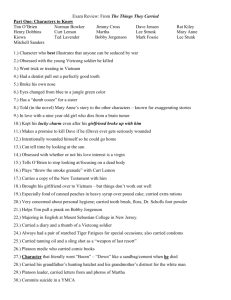

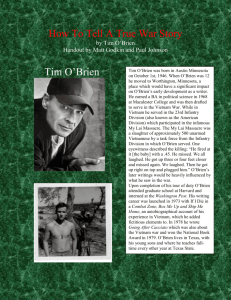

Brenda Lee IB HL English The Things They Carried Commentary: How to Tell a True War Story Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried is a work of metafiction that manages to test fiction in its very nature through the chapter, “How to Tell a True War Story.” The blurred line between reality and the imagination is explored by the given account—the reader is alienated and forced to think, does the truth matter in a war story? This chapter alternates in narration between O’Brien as a soldier and as a storyteller, examines the duplicity of whether story truth or happening truth is more vital, and explores the reactions which listeners and readers alike are to gather from these stories. O’Brien opens the chapter with three powerful words which set the tone for his debate throughout the chapter, “This is true.” (O’Brien 67). Narration of this chapter continues in first person where O’Brien narrates a story, analyzes its validity, and moves on to tell another aspect of the story, taking it apart. This syntax makes the reader feel interrupted and disoriented. You have barely had time to absorb the heartbreaking story before O’Brien switches gears, saying, “A true war story is never moral” (68). He sets qualifications for true war stories—“absolute and uncompromising allegiance to obscenity and evil” (69) and manages to clarify in his next pause in storytelling warning that “it’s difficult to separate what happened from what seemed to happen” and acknowledges people perceive things differently and thus will tell the stories differently (71). The stories are told with beautiful figurative language-personification, imagery, “war has the feel…of a great ghostly fog, thick and permanent. There is no clarity. Everything swirls,” and metaphor, in a tone where the reader is easily sucked in, only to be jarred awake with the factual and almost conversational tone of O’Brien’s analyses. To put things in context, the previous chapter, “Friends”, mentions Rat Kiley as the helpful medic for the dying friend. “Dentist” follows as a goodbye story to Curt Lemon. O’Brien includes foreshadowing and post-acknowledgement of both characters surrounding the chapter to bring them together and create an undercurrent within the chapter where the reader is forced to see how the order, though on the surface seem random, is actually predetermined. The core theme that a true war story cannot be factually believed is repeated multiple times throughout the chapter. One finds that “true” in war story does not mean the happening truth, but how well it relates to the appropriate emotional response, or story truth. The ultimate example of this is the heroic story of a man throwing himself onto a grenade to save his comrades. Whether or not anyone survives, “Absolute occurrence is irrelevant. A thing may happen and by a total lie; another thing may not happen and be truer than the truth…That’s a true story that never happened” (83-84). The author leaves the reader with mixed emotions, where they may feel cheated from the happening truth, but they also experience the emotion the storyteller wants them to feel— the story reality that “a true war story is never about war” and there is always an deeper meaning to be discovered(85).