IWQGES Progress report 1

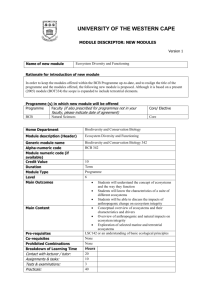

advertisement