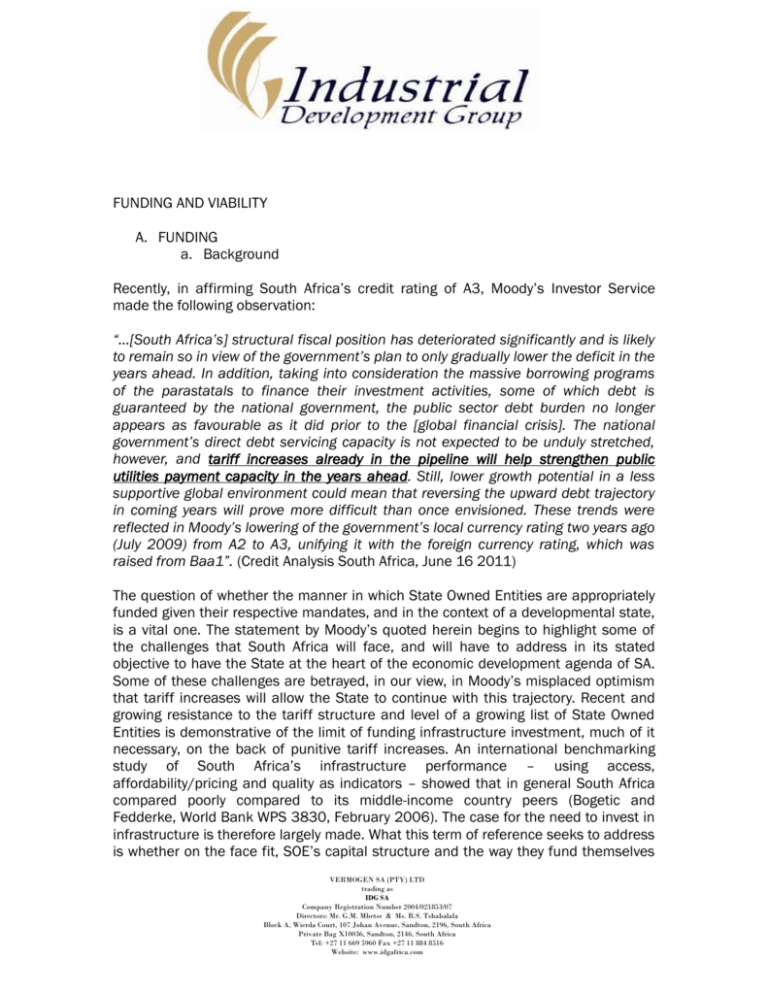

The viability and funding of SOEs

advertisement