Fact-Sheet-Action-5_IV-to-Oral-Therapy

advertisement

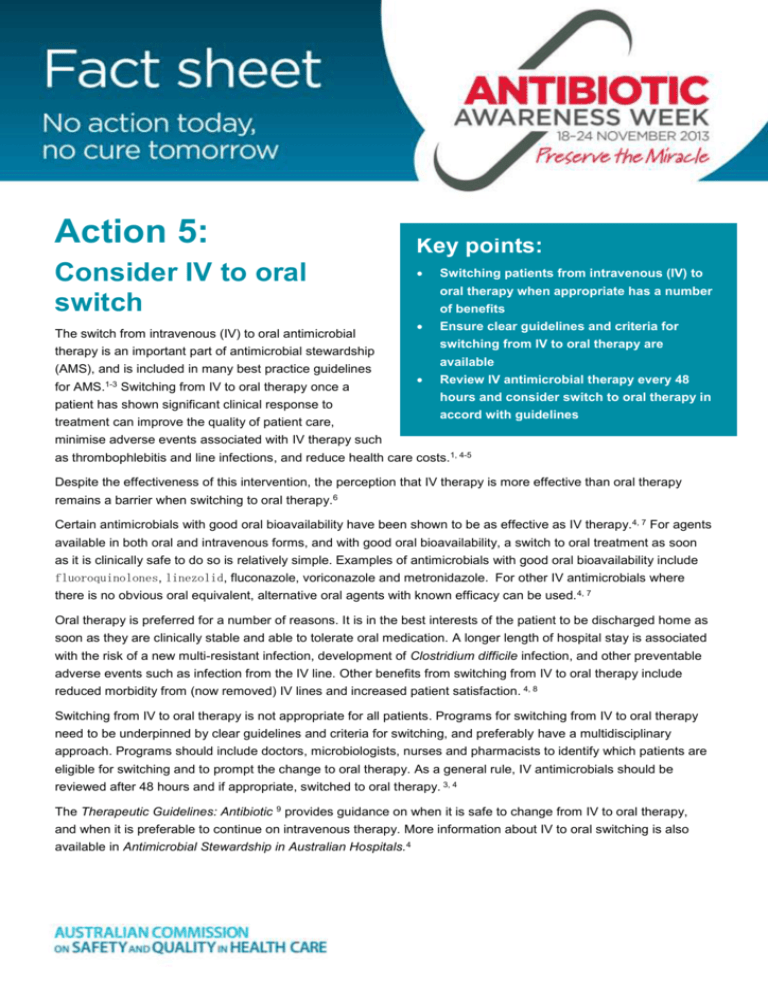

Action 5: Consider IV to oral switch The switch from intravenous (IV) to oral antimicrobial Key points: oral therapy when appropriate has a number of benefits for AMS.1-3 Switching from IV to oral therapy once a patient has shown significant clinical response to treatment can improve the quality of patient care, Ensure clear guidelines and criteria for switching from IV to oral therapy are therapy is an important part of antimicrobial stewardship (AMS), and is included in many best practice guidelines Switching patients from intravenous (IV) to available Review IV antimicrobial therapy every 48 hours and consider switch to oral therapy in accord with guidelines minimise adverse events associated with IV therapy such as thrombophlebitis and line infections, and reduce health care costs.1, 4-5 Despite the effectiveness of this intervention, the perception that IV therapy is more effective than oral therapy remains a barrier when switching to oral therapy.6 Certain antimicrobials with good oral bioavailability have been shown to be as effective as IV therapy. 4, 7 For agents available in both oral and intravenous forms, and with good oral bioavailability, a switch to oral treatment as soon as it is clinically safe to do so is relatively simple. Examples of antimicrobials with good oral bioavailability include fluoroquinolones, linezolid, fluconazole, voriconazole and metronidazole. For other IV antimicrobials where there is no obvious oral equivalent, alternative oral agents with known efficacy can be used. 4, 7 Oral therapy is preferred for a number of reasons. It is in the best interests of the patient to be discharged home as soon as they are clinically stable and able to tolerate oral medication. A longer length of hospital stay is associated with the risk of a new multi-resistant infection, development of Clostridium difficile infection, and other preventable adverse events such as infection from the IV line. Other benefits from switching from IV to oral therapy include reduced morbidity from (now removed) IV lines and increased patient satisfaction. 4, 8 Switching from IV to oral therapy is not appropriate for all patients. Programs for switching from IV to oral therapy need to be underpinned by clear guidelines and criteria for switching, and preferably have a multidisciplinary approach. Programs should include doctors, microbiologists, nurses and pharmacists to identify which patients are eligible for switching and to prompt the change to oral therapy. As a general rule, IV antimicrobials should be reviewed after 48 hours and if appropriate, switched to oral therapy. 3, 4 The Therapeutic Guidelines: Antibiotic 9 provides guidance on when it is safe to change from IV to oral therapy, and when it is preferable to continue on intravenous therapy. More information about IV to oral switching is also available in Antimicrobial Stewardship in Australian Hospitals.4 References and further reading 1. Dellit T, Owens R, McGowan J, Gerding D, Weinstein R, Burke J, Huskins W, Paterson D, Fishman N, Carpenter C, Brennan P, Billeter M, Hooten T. Infectious Diseases Society of America (ISDA) and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2007;44(2):159-177 2. Gould IM. Minimum antimicrobial stewardship measures. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2001;7(Suppl 6):22-26 3. National Health Service. Antimicrobial prescribing: a summary of best practice. Saving Lives: Reducing Infection, Delivering Clean and Safe Health Care. London: UK Department of Health, 2009. 4. Duguid M, Cruickshank M (editors). Antimicrobial Stewardship in Australian Hospitals. Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2011. 5. Drew R, White R, MacDougall C, Hermsen E, Owens R, Jr, Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Insights from the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists on antimicrobial stewardship guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society of Epidemiology of America. Pharmacotherapy 2009; 29(5):593-607 6. Schouten JA, Hulscher M, Natsch S, Kullber B, van der Meer J, Grol R. Barriers to optimal antibiotic use for community-acquired pneumonia at hospitals: a qualitative study. Qual Saf Health Care 2007;16:143-149 7. Owens R. Antimicrobial stewardship: concepts and strategies in the 21st century. Diagnositic Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 2008;61:110-128 8. Ramirez JA, Vargas S, Ritter GW, Brier ME, Wright A, Smith S, Newman D, Burke J, Mushtaq M, Huang A. Early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics and hospital discharge. Arch Intern Med 1999:159:24492454 9. Antibiotic Expert Group. Therapeutic Guidelines: Antibiotic. Version 14. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd; 2010 This document is intended for use by health professionals. It has been created from information contained in Antimicrobial Stewardship in Australian Hospitals 2011 and reviewed by clinical experts. Reasonable care has been taken to ensure this information is accurate at the date of creation. This fact sheet is intended to be used in it original version. It can be downloaded from the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care web page www.safetyandquality.gov.au/aaw2013 “No action today, no cure tomorrow” is adopted from the WHO World Health Day 2011. 2