Ethics and evolution overview- some arguments, Hume quote

advertisement

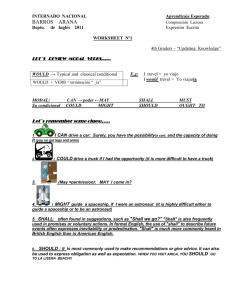

Notes on 2233 - Evolution and Ethics There are three main arguments that I want to spend some time on today. Two of them, as we will see, are seriously flawed or misconceived. But the third poses a classic, and extremely challenging philosophical puzzle. 1. The Argument From Animals. P1: Ethical constraints do not apply to animals. P2: If we evolved in a continuous way from animals, then if ethical constraints do not apply to animals, neither do they apply to us. P3: But we did evolve in a continuous way from animals. ___________________________________________ C: Ethical constraints do not apply to us. 2. The Argument from Natural Selection. P1: Evolution selects only the fittest to survive and reproduce. P3: It is futile and wrongheaded to resist natural law. P4: If evolution selects only the fittest to survive and reproduce, then to help the weak and unfit is to resist natural law. __________________________________________ C: It is futile and wrongheaded to help the weak and unfit. (This, like the first, takes many forms. A variation on it is to use it to justify ruthless and brutal competition with others as, again, simply a matter of the laws of nature.) 3. Norms and Nature. P1: There is no way to validly derive "ought" from "is." (This is a claim of Hume's; see the selection below for further remarks on this problem.) P2: Our status as natural beings who have evolved from other natural beings implies that we can be completely described (all the facts about us can be stated) using only sentences whose main verb is "is" or some other form of the copula. P3: If there is no way to validly derive "ought" from "is," and we can be completely described using only sentences whose main verb is "is" or some other form of the copula, then there is no way to derive any ethical claims about us (claims which must involve some form of "ought") from the facts about us. _______________________________________________________ C: There is no way to validly derive any ethical claims about us (claims which must involve some form of "ought") from the facts about us. On Evolutionary Ethics: 1. The key mistake- Widespread notion that evolution is a good thing (at least to evolutionists) and so we ought to encourage it / not stand in its way. (A related mistake: evolution is neither good nor bad, but it’s a law of nature, so again, we shouldn’t stand in its way (this time because it’s futile). This hard-nosed, let ‘em die approach fit nicely with Smith and especially Malthus and Ricardo’s approach to economics; suddenly charity (state or private) was viewed as immoral because it interfered with economic and (now) biological processes that were ultimately irresistible. It only prolonged/expanded the pain - increasing the supply of poor labour, gobbling up the national product. This is one reason that the Irish potato famine was so severe; policy makers felt they could not intervene in this “natural” economic process- note that this occurred before Darwin published On the Origin of Species. 2. A response: If our values are independent of evolution (and, from a certain point of view, the HIV virus is just as evolved (elegant, etc.) as we are; this doesn’t prevent us from regarding it as an evil, or from regarding efforts to destroy it as morally correct) then we are free to say what we value and act in its defense. This is neither wrong (evolution does not set the standards) nor futile (smallpox is gone). 3. But independence brings us to the last of our 3 arguments: the problem of descriptive naturalism vs. norms. Normative commitments involve an evaluation of things (people, actions, states of affairs) as good or bad. But the vocabulary of natural science simply doesn’t include evaluative terms like these—natural science is about description, not evaluation. What is the relation (if any) between the description of the world that science gives us, and our ideas about what we should do & how things should be? Hume on the IS/OUGHT gap: I cannot forbear adding to these reasonings an observation, which may, perhaps, be found of some importance. In every system of morality, which I have hitherto met with, I have always remark’d, that the author proceeds for some time in the ordinary way of reasoning, and establishes the being of a God, or makes observations concerning human affairs; when of a sudden I am surpriz’d to find, that instead of the usual copulations of propositions, is, and is not, I meet with no proposition that is not connected with an ought, or an ought not. This change is imperceptible; but it is, however, of the last consequence. For as this ought, or ought not, expresses some new relation or affirmation, ‘tis necessary that it shoul’d be observ’d and explain’d’ and at the same time that a reason should be given, for what seems altogether inconceivable, how this new relation can be a deduction from others, which are entirely different from it. But as authors do not commonly use this precaution, I shall presume to recommend it to the readers; and am persuaded, that this small attention wou’d subvert all the vulgar systems of morality, and let us see, that the distinction of vice and virtue is not founded merely on the relations of objects, nor is perceived by reason. A Treatise of Human Nature, (L.A. Selby-Bigge, ed.) 469-70.