also in Word - Australian Human Rights Commission

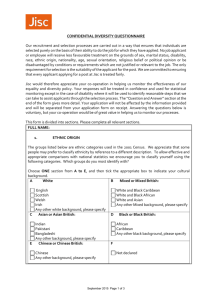

advertisement