Kelly 1 Meaghan A. Kelly ENGL 801 Dr. Mary Jo Reiff 5 November

advertisement

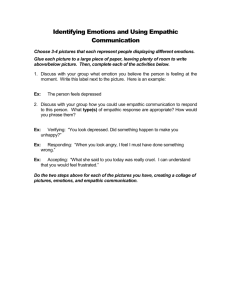

Kelly 1 Meaghan A. Kelly ENGL 801 Dr. Mary Jo Reiff 5 November 2012 Anxiety & Affect: Solidifying Empathic Pedagogy in the Academic Sphere Until recently, the academic and professional community has been averse and resistant to discussing emotion and its role within the academy and the classroom.While many extremely reputable and highly esteemed critics and pedagogical theorists have rejected the topic of empathy and its place in the discourse, it is no longer plausible to avoid the topic. In an era where school and the educational system has been forever changed by violent acts and a campaign against passionate emotions in light of that violence, the topics of affect, fear, and anxiety have been re-introduced to the pedagogical discourse. Affect and emotion have an unavoidable effect on both instructor and student in today’s composition classroom, and it was my motivation to find a way to use these negative notions productively to improve college students’ writing. I found my answer in Empathic Pedagogy, a teaching technique employed most prominently by Jeffrey Berman which focuses on the therapeutic qualities of using selfdisclosure in the composition classroom and how those qualities allow for more critical inquiry and thinking. Empathic Pedagogy allows the instructor and students to disclose highly emotional aspects of their lives, learn from one another, and continue in that understanding to move into a more critical line of inquiry and thinking. While the transfer of Empathic Pedagogy is a deeper understanding of what motivates one’s thoughts and beliefs, and therefore a higher ability to question, read, and write critically, the emphasis on emotions and self-disclosure has received much criticism. Major players in the field of Composition Studies, such as James Berlin and David Bartholomae, have denounced this Kelly 2 practice as “marginalizing...individuals who would resist a dehumanizing society, rendering them ineffective through their isolation” (Berlin Qtd. in Risky Writing 24). Berlin has taken Empathic Pedagogy, or rather its surface appearance, and opposed it against Critical Pedagogy, essentially pitting them against one another. This insufficient understanding of the theory paints a picture of the Empathic instructor isolating his or her students in their own little worlds, creating a self-centered and closed-off means of thinking. This view not only invalidates the recognition of emotion and its role in the classroom, it also demonizes instructors who employ the technique as doing a disservice to their students. Through a more thorough reading of Berman’s tactics, the truth is revealed that creating a classroom of empathy actually builds a community of higher understanding- because the students understand their own emotions better, they can then empathize with the emotions of their peers and begin a well-rounded line of inquiry based upon that understanding. Berman asserts that his pedagogy does the opposite of what Berlin has accused it of doing, and affirms its place within the academic discourse and pedagogical community. Berman relies heavily on the benefit of Empathic Pedagogy for the student, but the element of instructor fear and anxiety within the composition classroom also bolsters the pedagogy’s validity. As instructors, it is our responsibility to create an atmosphere that is most conducive to learning and progress. T.R. Johnson, in his article “School Sucks”, discusses the current environment that students encounter in composition studies: “One might turn to our discourse bout students’ ‘resistance’ to our pedagogies... ‘resistance’ is hardly the word for what it is not, after all, a pattern of repression but an explosion of rage”(624). Since the disturbing events at Columbine High School and the sequential acts of violence around the nation, the educational system has inextricably linked emotion with violence. This war on emotion Kelly 3 manifests itself in the categorization of any type of passion as potentially harmful. Whether a student shows an overwhelming notion of excitement or anger regarding their studies, it is automatically categorized as alarming, or possibly as an outburst. We tell our students to calm down, or what I have caught myself saying, to “take it down a notch”. By forcing them to repress these emotions it has caused them to harbor a resentment toward their studies, which can be seen as the root of the across-the-board ambivalence many instructors have recognized in their students. From time to time, this presents itself in frustration-driven rage, and Johnson explores the culture of anger, disappointment, and even violence that has taken over the educational system. Since it has been instructors who helped to create this environment, it is now the instructors’ responsibility to begin remedying it. While the benefit to students is clear, many instructors who consider this pedagogy are unaware of the growth that they will experience as instructors, since teachers using Empathic Pedagogy “‘have more positive self-concepts than low-level teachers’, ‘are more self-disclosing to their students’, ‘respond more to students’ feelings’, ‘give more praise’, ‘are more responsive to students’ ideas’, and ‘lecture less often’” (Rogers Qtd. in Empathic Teaching 100). Empathic Teaching is a cyclic pedagogical theory, as the actions of the instructor help to benefit student connection and writing, and the progress of student connection and improved writing then benefits the instructor- not only as a teacher, but also as a person. With such high stakes, Empathic Pedagogy is both attractive and risky to implement. Teachers today have an intensely difficult group of obstacles that keep them from succeeding in the academy. According to Geoffrey Sirc, the Composition Studies Community is now characterized by “a general sadness that the field has become materially impoverished, subsumed with a political simulation that has crowded out what I consider the poetic real: desire, beauty, Kelly 4 joy, drama, sadness, and loss... My lingering sense...is of a field that reads all the same books and shares the same notion of what counts as professional knowledge” (Qtd. in Micciche 443). The poor economy works with the obstinate attitude of academics who fiercely defend what they believe to be ‘worthy’ pedagogies in the professional academic community, and it becomes difficult for instructors to take any type of risk in the classroom that may leave them with a tenure denial or without a job at all. It is a battle between the inner passion for language and words that has driven us toward this profession, and the canonical and highly intellectual practices that are championed for being the epitome of academic. Therefore, it is essential to go about implementing a classroom based on self-disclosure in as thorough and careful a way as possible. Jeffrey Berman, a pioneer in implementing Empathic Pedagogy, understands this risk and explicates many of the intimidating aspects of creating a self-disclosure based classroom in his books Empathic Teaching and Risky Writing. Arguably, the most important aspect of this practical application is taking the risks head on and using them in a pedagogically productive way and avoiding any negative consequences from choosing such a strategy. In order to minimize the risks of personal writing, Berman proposes an approach to the classroom involving empathy, avoiding critique, respecting professional boundaries, grading Pass/Fail, retaining anonymity, pre-screening essays, balancing “risky” with “non-risky” assignments, utilizing conferences, and avoiding legal problems. Encouraging empathy, discouraging critique, using a Pass/Fail system, and retaining anonymity ensures the classroom is a safe space for writing, disclosure, and growth to occur. These tactics are mostly for the benefit of the student and the student’s comfortability in such an unorthodox environment, but also shield the teacher from any potential legal or bureaucratic ramifications. When everyone in the room feels safe and comfortable, the entire experience will be seen positively and will have more of a beneficial Kelly 5 effect on students’ writing. However, the section involving legal issues is clearly geared toward protecting the instructor. Any person involved in the higher education system will attest to the mountains of paperwork and Human Resources seminars that we must sign and take in order to convince our Universities that we understand and will abide to all of our legal responsibilities. I believe this aspect of our jobs is what contributes to this environment of fear and disappointment--we tread cautiously in our classrooms, avoiding any type of move that could potentially be seen as a risk. Berman begins this section with a frightening quote from Frederic Gale who writes in an article that, “writing teachers may respond to students’ writing in ways that are sensible, responsible, and ethical in their own minds and in the minds of their colleagues and still subject themselves and even their schools to civil or criminal liability” (Qtd. in Risky Writing 45). It seems as though the two areas of the law in which the writing teacher may find murky are privacy and intervention. Keeping students’ privacy in tact is essential to the selfdisclosure classroom, and as mandated reporters, instructors must fulfill that duty when they decide to intervene and report something that makes them believe their students’ welfare is at stake. This particular guidance helps to ensure the comfort of the instructor within the classroom, who can then move on to do the same for his or her students. While Berman outlines aspects that are more globally-geared, i.e. how to create an entire classroom based on the pedagogy of empathy, Rodney Simard offers a lesson-level strategy to help disarm the students and introduce them to the empathic classroom. In his article “Reducing Fear and Resistance by Attacking Myths”, Simard outlines various preconceived notions with which students enter the compostiion classroom. According to Simard, it is essential to address these myths and misconceptions immediately, especially if the instructor wants to establish the safe space that is most conducive to Empathic Pedagogy and create an environment in which Kelly 6 students’ writing will improve. This would occur on the first day of class. The instructor should separate his or her students into small workshop groups, and assign the following myths/misconceptions or set of misconceptions to each group: 1) Writing is a talent that only some people possess, and although others may attempt to learn how to do it well, they never will succeed; 2) Writing in the classroom has no real practical application in the outside world; 3) The key to good writing is learning all the rules- if you do that, you can’t go wrong; 4) There are too many styles and versions of writing that any amateur will ever be able to properly use (or will have to use, for that matter); 5) There is no room for personal or creative aspects in composition. As long as it sounds generic and run-of-the-mill, it will be right; 6) Books and teachers will give you step-by-step instructions to write: if you follow them, you’ll write well; 7) You’ll have to learn the type of writing your boss or other teacher will want you to use, so anything you learn now is useless; 8) If your elementary or high school writing background is weak, the writing required in college or a job environment will be too much for you to handle. Since this is a workshop setting, as long as students are talking about their assigned myths in any capacity, they are fulfilling the assignment. It’s possible to guide them with discussion questions, such as: Is this something you believe? What experiences do you have that either affirm or reject this notion? How has this notion affected your learning experiences? When reading this statement, how do you feel? Make sure that each group member puts in their opinion, even if it’s neutral. It’s essential to establish from the beginning that every student will be expected to contribute, and encourage an opinionated, experience-based contribution. Addressing these fears, anxieties, and disappointments in the system outright will create an atmosphere where it is not only acceptable to feel these emotions, but encouraged to address and explore them in an individual and unique fashion. Kelly 7 Because of the intensive introspective work that is required of the students and the person-centered pedagogical approach, the self-disclosure classroom is not for the light of heart. However, if one is to take on Empathic Pedagogy and apply it to one’s own classroom, the resources and research done on the topic create a solid foundation upon which an instructor can stand, particularly those of Jeffrey Berman, an instructor and author with 30 years of experience conducting a self-disclosure classroom. With Berman’s theoretical and experiential knowledge, the empathic teacher can put Simard’s in-class activity to work in laying the groundwork for a safe and open space in which real learning and growth can occur. Works Cited Berman, Jeffrey. Empathic Teaching: Education for Life. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 2004. Print .--. "Empathy, Trauma, and Forgiveness: Classroom Implications." Empathic Teaching: Education for Life. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 2004. 95-137. Print. --. "Introduction: Making a Difference in Students’ Lives." Empathic Teaching: Education for Life. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 2004. 1-35. Print. Kelly 8 Berman, Jeffrey. "Risky Writing: Theoretical and Practical Implications." Risky Writing: SelfDisclosure and Self-Transformation in the Classroom. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 2001. 21-71. Print. Johnson, T. R. "School Sucks." College Composition and Communication June 52.4 (2001): 620-50. JSTOR. Web. 22 Oct. 2012. Micciche, Laura R. "More Than a Feeling: Disappointment and WPA Work." College English March 64.4 (2002): 432-58. JSTOR. Web. 29 Oct. 2012. Simard, Rodney. "Reducing Fear and Resistance by Attacking the Myths." College Teaching Summer 33.3 (1985): 101-07. JSTOR. Web. 22 Oct. 2012. Meaghan A. Kelly ENGL 801 Dr. Mary Jo Reiff 5 November 2012 Annotated Bibliography Allen, Michael. "Writing Away from Fear: Mina Shaughnessy and the Uses of Authority." College English April 41.8 (1980): 857-67. JSTOR. Web. 20 Oct. 2012. Annotation: This article begins by shedding light on a recent review of Mina Shaughnessy’s Errors & Expectations, and the harshness of that review. Shaughnessy’s book, which is sitting on my bookshelf as we speak, was a keystone piece of research when it came to the composition classroom. Allen decides to to take on the negative review, and give his opinion regarding the theory and execution of that theory that the book puts out in to the discourse. Allen believes that Shaughnessy’s instinct to put emotion first in the writing process above all else is one that merits defense, as the emotional realities of students are what must be addressed first in the writing classroom. Allen positions the two authors, Shaughnessy and her critic, against one another, and Kelly 9 describes how Shaughnessy’s student-centered approach and experiential evidence work as the more plausible and effective classroom implementation technique. While this source is valuable in that it emphasizes the validity of the canonical piece of work, it tends to be repetitive. I think this source would be useful to consult at the beginning of the process of considering Empathic Teaching as an option, but essentially all of the elements are referenced in more up to date and relevant works to the point where they are easily understood. Berman, Jeffrey. Empathic Teaching: Education for Life. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 2004. Print. --. "Empathy, Trauma, and Forgiveness: Classroom Implications." Empathic Teaching: Education for Life. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 2004. 95-137. Print. Annotation: In this chapter of Berman’s book on Empathic Pedagogy, the author takes the reader step by step through the obstacles and successes that come along with employing this teaching technique. He first positions the practical application within the psychoanalytic discourse, and draws upon previous psychoanalytic pedagogy to create a foundation for the application. Berman takes the time to address resistance to the empathy that is central to his classroom strategy, and concludes the section by solidifying its validity within the academic sphere. Since the self-disclosure classroom revolves around the identification and acceptance of personal trauma, the author offers keystone information to understanding and utilizing this trauma, and gives plenty of resources so the reader is able to develop a fully rounded understanding of the technique. From repression to PTSD, Berman is careful to give a wide scope of possibilities in the Kelly 10 classroom. The chapter is then ended with a section on forgiveness, which is the binding principal and goal regarding the trauma that will be addressed through the various writing exercises. I believe this source is very useful to my research and my colleagues’ understanding of the issue, particularly because it offers essential details to build the bigger picture of Empathic Pedagogy, and does not assume that the reader has any prior experience in the field. --. "Introduction: Making a Difference in Students’ Lives." Empathic Teaching: Education for Life. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 2004. 1-35. Print. Annotation: Berman’s introduction to his book Empathic Teaching introduces central concepts to the reader that must be kept in mind throughout the process of Empathic Pedagogy. He starts with anecdotes about students who wrote to him or approached him after taking his self-disclosure based courses and who saw him as an influential person in their lives. This allows him to move toward what one must expect after adopting this pedagogy. The most obvious is that the teacher becomes a type of attachment figure, and the aforementioned students’ words came out of a place that recognized that aspect of the teaching. Becoming a teacher that exudes a type of warmth is what Empathic Pedagogy promotes, and Berman covers many aspects of what comes with being a warm teacher. This introductory chapter is particularly useful in that it explicates foundational concepts for the pedagogy and later, the application. It portrays the teaching technique in a truthful light, covering the obstacles and successes that help the reader create a fully rounded view. This will be helpful for myself and my colleagues because it offers many of the Kelly 11 introductory concepts that need to be established before one dives into the dense theoretical and then intensely pragmatic discussion of Empathic Pedagogy. Berman, Jeffrey. "Risky Writing: Theoretical and Practical Implications." Risky Writing: SelfDisclosure and Self-Transformation in the Classroom. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 2001. 21-71. Print. Annotation: Jeffrey Berman, in his chapter involving “Theoretical and Practical Implications” covers the criticisms of his stance regarding empathic pedagogy and his involvement of “risky writing” (therapeutic writing based in self-disclosure), particularly Bartholomae’s vehement rejection of the practice. Berman posits his theory snugly in the academic discourse and even concedes that some of Bartholomae’s dangers are present, but they can be avoided by making specific pedagogical choices in the classroom. Berman asserts that his theory is academic and does not substitute feeling for thinking-the two are not mutually exclusive, and they occur together in the classroom with risky writing. Berman covers the theoretical and moves toward the practical by covering every aspect that surrounds the fear in incorporating self-disclosure in the classroom. From making responsible and sound legal choices to grading policy, Berman thoroughly tackles the gritty decision-making that has to be done with such a deviant pedagogy. This chapter will further our understanding of empathic teaching in that it makes the theory a reality, and also defends the theoretical position the pedagogy takes within the larger discourse community. By offering multiple criticisms of the technique and countering them with experiential knowledge, Berman not only tells us how this would work in the academic sphere, but shows us as well. Kelly 12 Chandler, Sally. "Fear, Teaching Composition, and Students' Discursive Choices: Re-Thinking Connections Between Emotions and College Student Writing."Composition Studies Fall 35.2 (2007): 53-70. Academic Search Complete. Web. 26 Oct. 2012. Annotation: Similarly to Simard, Chandler opens by addressing a pattern in the composition classroom: cliches. Chandler believes that students resort to what they believe to be reliable stand-by conventions due to the anxiety and fear that comes with writing studies and composition courses. Ideally, instructors wouldn’t have their students touch a cliche with a ten-foot-pole, but they continue to encounter them in their student work. In order to parse out the environment of anxiety, Chandler starts with reflective essays written by writing center tutors regarding their very first tutoring appointments. While each tutor became anxious and full of self-doubt before the appointment, they began to accept their emotions and understand them better once they interacted with their first tutees, and realized that they were both feeling the same anxiousness in the situation. Through empathy for another, the tutors were able to better understand and overcome the negative emotions they were experiencing. Writing about this experience through self-disclosure aided in avoiding the sweeping generalizations (and safety) that cliches provide for a novice writer. However, most writers in the beginning composition classroom have yet to self-actualize and self-identify as novice writers- they perpetually see themselves as amateurs. This step, according to Chandler, is essential to success in the college setting. The fear and self-doubt that pervades the classroom is crippling to some students’ progress, and Chandler moves on to practical applications to start using it in a productive way. The author is very careful to differentiate herself from those who Kelly 13 apply Empathic Teaching in a self-disclosure classroom to that of the trauma in their students’ lives. She recognizes the similarity, but is sure to highlight that her application of Empathic Teaching is operating at a level of emotion, but not a level of trauma. Downs, Douglas, and Elizabeth Wardle. "Teaching about Writing, Righting Misconceptions: (Re)envisioning "First-Year Composition" as "Introduction to Writing Studies"" College Composition and Communication June 58.4 (2007): 552-84. JSTOR. Web. 20 Oct. 2012. Downs & Wardle’s article goes well with Rodney Simard’s, in that they both reference misconceptions regarding the composition classroom. However, Downs & Wardle take a different approach to these misconceptions, and instead of using them as content for the classroom, uses them as the catalyst to reform First Year Composition programs. The authors systematically address the misconceptions of FYC within the academic scope. The sections are separated by headers describing the misconception they address: “Academic Discourse as a Category Mistake”, “The Open Question of Transfer”, and “Resisting Misconceptions”. The first section asks the question, can FYC programs fulfill the goals and expectations that have been set for them? The authors then describe how writing, although it has shared elements among the disciplines, needs to be learned within the scope of a chosen field in order for mastery to occur. The second section posits that in order to make the discipline of writing have any authority of the courses, the FYC system needs to be reformed through resistance of conventional methods. Lastly, the misconceptions in “Resisting Misconceptions” are actually referring to the conventional practices of the FYC classroom, and addresses this issue by stating that the FYC system must take a realistic approach to the types of writing that will be Kelly 14 used in the classroom. Once these misconceptions are addressed, the article moves on to the practical applications of changing an FYC program to Introduction to Writing Studies. The content moves on to possible assignments within the classroom. The article then moves in to case studies, in which the application of this theory was implemented and the reader is given results and experiential evidence. This is particularly helpful, as many sources focus solely on the theoretical and do not give as much practical information. Harris, Judith. "Re-Writing the Subject: Psychoanalytic Approaches to Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy." College English November 64.2 (2001): 175-204. JSTOR. Web. 19 Oct. 2012. Annotation: Harris begins her article by addressing the divide between creative writing and composition studies. She moves in to discussing how creative writing and expressivist pedagogy work together, and are innately similar in teaching composition. English departments have conventionally kept creative writing and composition separate, but this piece argues that they should be intertwined, as they are mutually beneficial. Harris begins interweaving aspects of psychoanalysis into the discussion, particularly when it comes to the benefits of personal disclosure in both (and one day, the same) classrooms. When a student is engaged in self-exploration and self-expression, they are receiving scaffolding in order to reach out to their larger community and understand those around them. It’s clear that Berman has used Harris as his jump-off point, in that she creates the foundation upon which he builds his theory of Empathic Pedagogy. This keystone piece allows me to further understand this area, as Harris delves deeper in to Kelly 15 psychoanalysis and gives crucial historical and theoretical information which Berman assumes the reader already knows. Harris moves on to classroom implications, and it is clear that her experiential observations have influenced her theoretical and practical approach, as well as Berman’s. Johnson, T. R. "School Sucks." College Composition and Communication June 52.4 (2001): 620-50. JSTOR. Web. 22 Oct. 2012. Annotation: Higher education, in its highly structured and traditional reputation, has so incredibly opposed the emotionally-propelled, reactionary style of learning that it has actually demonized it. T.R. Johnson recalls the violent school yard rhymes of his childhood, those that point to the visceral and oppositional environments that many students either create or exist in from a very early stage of education. These visceral reactions are immediately seen as negative, and have become demonized within our culture and often viewed as the catalyst for school tragedies such as the Columbine shootings. Johnson asserts that from the beginning of educational history, even pointing to the preliterate, an outburst of emotion was seen as the starting point of true understanding and therefore true creation. It is our educational system that has used a negative lens against it, and consequentially puts a stop to any type of emotional reactions (good or bad) in the classroom. Johnson believes that it is the composition studies’ re-immersion in to the conversation of higher education that offers the opportunity to change this atmosphere of fear and anxiety toward involving emotion in the classroom. He thinks every classroom should be one of discussion and laughter, finding the cracks in the structural boundaries and actually celebrating them in the Kelly 16 process of composition. That is the only way to re-create the environment and dispel every instance of opposing spontaneous emotion and rather embrace it. This article will be very useful in my both my paper and presentation, as it offers both an exploration of the issue and practical applications to begin remedying it. Micciche, Laura R. "More Than a Feeling: Disappointment and WPA Work." College English March 64.4 (2002): 432-58. JSTOR. Web. 29 Oct. 2012. Annotation: Laura R. Micciche addresses multiple aspects of emotion and the effect it has on the classroom, specifically regarding WPA work. Although most of the article is geared toward WPA work, it does make some points that are applicable to the composition classroom in general. Specifically, Micciche explores the violence-filled culture that is the education system in America. After exploring this issue, Micciche goes futher in explicating how this culture produces anxiety in both the student and teacher. This anxiety builds in that expectations are assigned to the class and the course, and when those expectations are not met, both student and instructor become disappointed in the system. This continues to create negative emotions toward the course and those involved. Essentially it is this vicious cycle that is the every day concern of the Writing Program Administrator, and this article explores innovative ways to break the cycle and work to dispel the environment of fear, so that both instructor and student are more comfortable in their roles within the composition classroom. I find this article to be particularly useful in that it offers a position that composition instructors are not privy to: the Writing Program Administrator, and how the admins would go about helping to lay the foundation for a more comfortable, safe atmosphere in the classroom. I think this piece would work Kelly 17 particularly well with the Johnson article, as it references the same violent environment that Johnson explores during the first half of his work. Simard, Rodney. "Reducing Fear and Resistance by Attacking the Myths." College Teaching Summer 33.3 (1985): 101-07. JSTOR. Web. 22 Oct. 2012. Annotation: Rodney Simard believes that before any teacher can begin to approach the problems regarding student writing, let alone begin to remedy them, the students’ attitudes and pre-conceived notions about the writing classroom must be addressed. This article bypasses theoretical application and goes straight to the experiential, as Simard has found success with this approach in his own classroom over and over again. This success has been found through addressing eight specific myths about education and writing, and allowing the class to participate in a workshop atmosphere in order to parse these issues out. The myths that Simard feels are most important to cover are the following: 1) Writing is a talent that only some people possess, and although others may attempt to learn how to do it well, they never will succeed; 2) Writing in the classroom has no real practical application in the outside world; 3) The key to good writing is learning all the rules- if you do that, you can’t go wrong; 4) There are too many styles and versions of writing that any amateur will ever be able to properly use (or will have to use, for that matter); 5) There is no room for personal or creative aspects in composition. As long as it sounds generic and run-of-the-mill, it will be right; 6) Books and teachers will give you step-by-step instructions to write: if you follow them, you’ll write well; 7) You’ll have to learn the type of writing your boss or other teacher will want you to use, so anything you learn now is useless; 8) If your elementary or high school writing Kelly 18 background is weak, the writing required in college or a job environment will be too much for you to handle. As one can see, Simard covers everything from beginning notions about writing all the way to the fears and anxieties students may have about higher education or the ‘real world’ environment. Simard offers all types of student responses, as well as suggestions to field these responses and spark a productive and explorative discussion among students. Doing this from the beginning of class will pave the way for a more open and safer environment for composition and learning. For those of us that have an aversion to opening up personal dialogue within our classrooms and as topics for composition assignments, this source helps us to break through that fear by safely positing ways to go about broaching these subjects. Specifically because this article offers a way to begin a course in creating a positive, non-judgmental and even question-conducive atmosphere which would be the ideal way to begin a class if one were trying to base the course off of personal narrative and breaking the boundaries of traditional composition class form.