ABBEYDORNEY PARISH ~ ST

advertisement

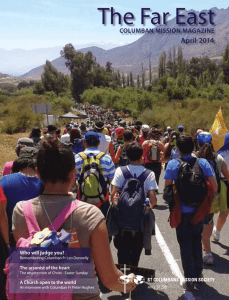

The Presbytery, Abbeydorney. (066 7135146) abbeydorney@dioceseofkerry.ie rd 33 Sunday in Ordinary Time, 17th November 2013 Dear Parishioner, This time last week, we were getting early reports on the huge disaster caused by the typhoon (Haiyan) in the Philippines. In the week that has passed, we have been reminded in newspaper, radio and TV coverage of the scale of the disaster and the huge need to help survivors. As a result of the urgent need for help, the church collection which was announced last weekend, to help the people of Syria in their crisis, will be for both places. The following information comes from a Trócaire letter sent to parishes in the past few days. ‘This is a major humanitarian crisis and Trocaire is responding with our Caritas partners – we have already committed €100,000 to support their work. We are also supporting the work of Irish missionaries in the affected regions. The international Caritas Network is putting together an international team to support the effort and a Trócaire staff member is part of that team. Trócaire’s partner, Catholic Relief Services (USA, has sent rapid assessment teams to the typhoon-hit regions. Eight thousand tarpaulins are currently being distributed to provide temporary shelter for survivors. Agencies working on the ground are also assessing water and sanitation needs to prevent the spread of water-bourne diseases, which will be one of the immediate threats to survivors. Irish public donations will be used to provide water, food, shelter and medicines to those who are most affected.’ It is a coincidence that, at the time the typhoon hit the Philippines, I had received a short little holiday report from Orla Mahony, a pupil in Kilflynn School, of her family’s summer trip to her mother’s home. “During our holiday in the Philippines, we went to my mom’s hometown of Pamplon. We attended Mass in the large church there, which is about two hundred years old. When we went in, we saw two women selling candles at the side door, which led into a room full of statues. The patron saint of Pamplon is St. Francis Havier. The Mass was celebrated in the Tagalog language and also in English.” I am sure I can speak for all parishioners, when I say that our thoughts and prayers are with all who are suffering because of natural disasters or because of conflicts of one kind or another. (Fr. Denis O’Mahony) There Is No Death! Whether you’re a parent or a priest, it is difficult to find the right words to comfort the bereaved. Recently I met a priest friend in Dublin’s Botanic Gardens. It was a convenient venue for him as he was coming from a funeral in Glasnevin Cemetery, the third burial he had officiated at in a week. I had attended five funerals in the previous two months. We discussed how difficult it is to find words to comfort a bereaved family. At one of the funerals I attended, the priest said, “There is no death.” I saw the amazed reaction of teenagers near me. A 52-year-old man, the father of one of their classmates lay in the coffin. Everybody in that congregation knew the man was dead. Even though what the priest said was correct, I saw little comfort for the family in those words. At another funeral, the priest said this was not a time to grieve. It was time to celebrate the life of the deceased. As his grandchildren brought up his paint brushes, a painting he loved, a football jersey and a picture of his wife who predeceased him, there was a sense of celebrating a rich, fulfilled life. There was hardly a dry eye in the church during the prayer of the faithful. The man’s son got so choked up with emotion that he struggled to finish the prayer. Crying is a normal grief response to the death of someone you love. Grieving is what people do when they attend a funeral. My friend said that most priests want the Mass to be a meaningful celebration. They feel uncomfortable, when they don’t know the deceased personally. There’s bound to be awkwardness when the death resulted from an accident, a suicide, or when there is a bitter family feud. I asked would he like my views on the words of comfort that I would find meaningful. He offered a polite ‘no’ and changed the topic. Finding words of comfort is an even greater challenge for the parent of a teenager in shock and grief at the death of a friend. Almost every teenager knows someone who has died by suicide. Teens seem to think of tragic deaths as cruel, tragic and painful. Death is frightening. It’s difficult to find meaning when you watch a coffin lowered into a dark, cold grave. After teenage suicide, schools offer counselling to students to help heal the trauma. One fear is of copycat suicides; another that students will get into a cycle of grief and guilt because they blame themselves for doing something that led to unhappiness. When bullying is involved, students who stood by and did nothing to report what went on may feel enormous guilt. No loving parent or friend wants a child to grieve so long that they lose the desire to study or want to stop living. When someone is so overcome with grief that he or she cannot go on, the upset is not about the bereaved. The healing of such strong emotions starts with the awareness that inconsolable grief is triggered when some external upset affects an existing deep hurt that needs to be addressed. Whether you are a priest or a parent, what you say to comfort others reflects your own belief about death and the afterlife. Author Iyanla Vanzant says, “You grieve because you will miss the person. If you are not careful, the spirit of grief can take over your life, causing you to miss the joy, peace and love that lie within you and ahead of you.” Her suggestion is that you grieve until you feel comforted enough to live in gratitude and without fear. “Grieve until you can accept what has happened without resistance. Grieve until you can let go of what was.” Until Today! is her beautifully written book of daily reflections. On 15th July, she writes, ‘People never really die. They leave their bodies. They end their physical existence in order to continue their spiritual journey in another form, on another plane. A person who has entered the realm of existence we call death is never beyond your love. Once you know a person, you will always know a person. Once you have loved a person, your love will keep them alive.’ Another Vanzant insight is, ‘Death is an essential part of life that teaches us to believe in what we can see. Life continues after death as long as you remember that warmth of another’s smile, the gentleness of their touch, the meaning they brought to your life.’ The wisdom in her words gives meaning to the priest’s statement “There is no death.” This rings true for believers and non-believers alike. A funeral will always reflect people’s grief, as well as being a celebration of a life well lived. In the future, when I go to a funeral, I’ll have the comfort of understanding that “There is no death.” (Carmel Wynne in her column, Christian Parenting, in Reality Magazine, November 2013.) God is in everyone’s life. Even if the life of a person has been a disaster, even if it is destroyed by vices, drugs or anything else – God is in this person’s life. You can, you must try to seek God in every human life. Although the life of a person is a land full of thorns and weeds, there is always a space in which the good seed can grow. You have to trust God. (Pope Francis in Reality Magazine, November 2013) St. Columban: The memorial of St. Columban occurs on 23rd November. Columban or Columbanus is remembered as one of the greatest of the Irish missionary monks. Born in Leinster around 543, he became a monk in Bangor. In 591, desiring to ‘go on pilgrimage for Christ’, with the approval of the abbot, St. Comgall, he set out with twelve companions and came to Burgundy. He founded monasteries at Annegray, Luxeuil and Fontaine. These monasteries followed the severe Irish rule, which included absolute obedience and corporal punishment. Columban’s monasteries also kept the Irish date for Easter, introduced Irish penitential practices and having a bishop subordinate to the abbot. Banished for his criticism of the moral life of a local king, he made his way through Switzerland to Bergenz on Lake Constance, in modern day Austria, working as a missionary with St. Gall for some time. Then crossing the Alps into Lombardy, he founded his last and greatest monastery at Bobbio around 613. He died there on 23rd November 615. (Columbanus in his own words by the late Cardinal Tomás O Fiaich, first published in 1974, is available again from Veritas Publications.) The Deep End * Fashion changes, style endures. We are reading the final chapters of the Gospel of Luke for Year C. Jesus is in Jerusalem and the passages we hear are about end times. The people gathered are obviously excited, having seen how magnificent the Temple is, having coming ‘up from the country’ and Jesus is trying to calm them down. The time for excitement might not be just yet. Jesus reminds them, and us, that these things are short-lived and we should not be too bothered about ‘fine stonework’ and ‘votive offerings’. These things do not last. Jesus’ main warning is not to believe many who will come claiming to know when the end times will be. A series of quotations from Jesus follows in which he gives comfort to the people about various crises that will happen. Luke is almost giving us a subsequent history of the Christian community. It is not all doom and gloom, but we need to take perspective and look at the bigger picture. Endurance is the message of today’s Gospel. The people of Jerusalem will witness the destruction of the Temple, the disciples will face persecution, people of faith will have tough times ahead. Whatever crisis may come, Jesus is affirming us to keep going, to stay focussed and not be afraid. ‘Lord, when we are young, we think that we become great through our achievements. Life has taught us the truth of Jesus’ words: ‘It is by endurance that we win our lives.’ (Michel De Verteuil’) (The piece on St. Columban and the Deep End are taken from Intercom Magazine, November 2013)