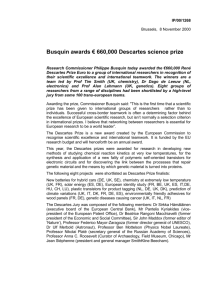

Descartes and Knowledge

advertisement

Descartes and Knowledge Epistemology: What is knowledge? What things can be known? How can we come to know them? Before 1600 there is a conception of knowledge beginning with the Greeks on which knowledge is true belief justified by a proof or demonstration. The exemplar here is mathematical, and particularly geometric, proof. It is a characteristic of knowledge so conceived that it cannot be grounded in empirical evidence, in experience or observation. Those who worked in the domains we know call science, in particular in physics and medicine, were no less committed to this conception of knowledge than anyone else; they reasoned out theories of how things worked by ‘first principles’, without grounding their theories in empirical observation. This conception of knowledge was radically revised by the scientific revolution. Knowledge was to be grounded in empirical observation, and ‘proof’ or ‘demonstration’ no longer required the kind of guarantee of certainty characteristic of mathematical proof. The revolution occurred over the course of the 17th century, beginning with Galileo and Kepler on the continent in the first decade of the 1600s, and culminating in the work of Boyle and Newton in England in at the very end of the 1600s. In between truly amazing advances in physics and mathematics occurred. During this time people were not only working out new mathematics and new theories of how the world worked, the very same people were also engaged in re-conceiving the very idea of knowledge, and the related notions of justification and evidence. Among the most important figures in this century of change was Descartes. Descartes was a mathematician, philosopher and scientist. His contributions to mathematics included analytic geometry and the ‘Cartesian coordinate’ system of graphical representation of equations. He also developed a (largely mistaken) conception of mechanics, and an important (though false) conception of psychology. Finally, he was among the very first to fully explicate a complete epistemology. Descartes epistemology breaks ranks with the standard, received view on which knowledge requires something very like a mathematical proof (this view had its origins in Aristotle, and was at the time still defended by a group of people known as Scholastics). Unlike the scholastic accounts of knowledge, Descartes thinks nearly all knowledge must be grounded in experience, in perceptions of the world. On the other hand, Descartes is not nearly so radical as others, such as Boyle, in that he thinks knowledge does require a kind of certainty—one can know only if the grounds for one’s belief are infallible, and known to be infallible. This double commitment raises a puzzle. It turns out not to be at all clear how knowledge could be infallible and also grounded in empirical evidence, in sense perception, at the same time. Descartes formulates the puzzle in the first mediation, and begins an attempt to resolve the puzzle in the second. We are concerned with the puzzle itself. For Descartes, knowledge is justified true belief: one knows that P (where P is some proposition, or assertorical sentence) only if 1) one believes P, 2) P is true, and 3) one has a justification for believing P to be true. One is justified in believing P only if one has reasons R (these will be other propositions) for believing P such that 1) if R are true, then P must be true as well, and 2) R is known to be true. Descartes thinks nearly all knowledge is grounded in perceptual experience—that is, perceptions provide the reasons which justify one’s beliefs. The simplest kind of knowledge so grounded are perceptual beliefs—beliefs that things are as one experiences them to be. So, e.g.: The coffee cup is blue. I am here in class. Glymour is wearing a grey shirt. One believes these things because one perceives the world in the way described by these sentences—one sees the blue cup; one sees the classroom, the professor and one’s fellow students, one feels the desk, and hears the prof. droning on about epistemology; one sees Glymour and his grey shirt. The experiences themselves can be described without presuming that the world is as it is experienced; e.g. one can say: ‘The cup seems blue to me.’ or ‘I seem to see Glymour in a grey shirt’, or ‘I am having the experience of listening to a lecture.’ These claims will be true even if the cup is not blue, even if you are really at home in bed dreaming rather than here in class, and so on. When a perception really does represent the world as it is, the perception is said to be ‘veridical’. Your experience of the blue coffee cup is veridical just in case there really is a blue coffee cup on the desk. If you are merely dreaming this, then your current experience of the blue coffee cup is non-veridical. These ‘seeming’ sentences, sentences which are about what one experiences rather than about the world, provide the reasons for believing the world is as you experience it. The justification for believing Glymour’s shirt is grey includes essentially the claim ‘I seem to see Glymour in a grey shirt.’. Given this background, we can now consider Descartes’ puzzle. The puzzle is presented as a dialectic relating three arguments. Descartes’ presents an argument which says, given the assumptions so far, one cannot know about the external world, because one cannot know the simplest of perceptual beliefs. One cannot, if fact, even know that the external world exists. Descartes then considers a response which would save some of our knowledge, though not very much. Finally, he responds to this argument, re-establishing our ignorance of the external world. The Dream Argument (argument 1). All perceptual beliefs are grounded in our experience, in perceptions. For every veridical perception there is another, identical in content, which is non-veridical (e.g. a dream perception with exactly the same content). One cannot differentiate between veridical and non-veridical perceptions (precisely because they are identical in content). But if a perception is non-veridical, then the perceptual beliefs it grounds are false, and hence cannot be known. Therefore, one cannot know even those perceptual beliefs which are grounded on veridical perceptions, because one cannot know that these perceptions are in fact veridical (i.e. the inference from, ‘It seems to me that the cup is blue.’ to ‘The cup is blue.’ is fallible). Since no perceptual belief is known, one cannot even know that there are such things as cups, classes and professors—perhaps all your experiences with that sort of content are non-veridical. Therefore, one cannot even know that there is an external world, or that it contains the kinds of physical objects we normally think it contains. Descartes considers a response to the argument. The response turns on the idea that perceptions depend on concepts. One cannot perceive a blue coffee cup on the table, one cannot have an experience of that kind, unless one has the idea of a coffee cup. The argument further claims that the human mind is not capable of inventing ideas de novo. The mind can modify ideas it already has, but it must get the original ideas from somewhere else. So, e.g., we can invent the idea of a unicorn if we already have the idea of ‘horse’ and ‘horn’. But those ideas must come from somewhere else, and without already having them, we could not combine them to produce the idea of a unicorn. So certain basic ideas must have there source in something external too us. Among these ideas are those of physical object, space, and time. The Rebuttal (argument 2). We may be deceived about whether any particular perceptual belief is true, because we are unable to tell whether the perception on which it is grounded is veridical. Hence we cannot know whether we are now in a classroom. But we cannot be deceived by all such perceptions, for the to have the experience of being in a classroom we need certain ideas— those of other people, professors, students, rooms, lectures, and so on. Those ideas must have a source. Either that source is something outside us, or the ideas are invented by us by modifying other ideas, which in turn must have a source outside us. Hence, although we cannot know that we are now in a classroom, we can know that there is an external world, filled with objects that include people and rooms, for if there were no such objects we could never have come to have the ideas which make it possible for us to have the experience, veridical or not, of being in a classroom. Finally, Descartes offers a response to the rebuttal. The response considers an alternative source for the ideas we must have in order to have the kinds of experiences we do in fact have. This source is an all powerful evil demon, bent on deceiving us. It is important here to note that Descartes does not believe there is such a demon, and he does not think you ought to believe this either. He claims only that you cannot know that no such being exists, and that therefore you cannot know anything else either. The Evil Demon Argument (argument 3). Nothing you know is inconsistent with the idea that you are a mind in a void being fed experiences (all non-veridical) by an evil demon. Were this the case, everything you believe about the external world would be false. Hence, though there must be some external source for the concepts in terms of which you experience the world, that source need not be the external world itself, nor need it include any of the objects or properties one normally thinks it includes. Therefore, one cannot know that the external world exists, nor can one know anything about what objects it includes, and finally, one cannot know any perceptual belief. Descartes attempts to resolve the puzzle. There are four steps to the resolution. First, Descartes notes that there are some things we can know because they will be true even if the evil demon exists; e.g. one can know that one exists and one can know the content of one’s experience (e.g. one cannot be mistaken about being in pain, or about whether the cup appears blue). Secondly, one can know that certain basic (deductively valid) inferences are truth preserving. Using these inferences, one can prove that God exists, and is beneficent. Because God is beneficent, he cannot be a deceiver; consequently there is a mark which distinguishes veridical from non-veridical experiences. Veridical experiences involve ‘clear and distinct ideas’. Using the basic inferences and clear and distinct ideas, one can reconstruct as knowledge almost all of the things we thought we knew. There are two standard responses to Descartes. No one now thinks Descartes resolution of the puzzle actually works (the proofs of God’s existence are regarded as incorrect, and even if they weren’t, the idea of ‘clear and distinct ideas’ won’t do the work Descartes requires of it—how can you tell whether an idea is clear and distinct?). Given this failure, one response is to accept the conception of knowledge and deny that we know very much of anything, and in particular to deny that we know anything about the external world. This position is known as Cartesian Skepticism, and is now generally developed by appeal not to an evil demon, but to a mad scientist who has your brain in a vat, hooked up to electrodes, by means of which he determines your, systematically mistaken, experiences. A second response is to deny the conception of knowledge with which Descartes is working. In particular, one must hold that knowledge is fallible—one can know even if the reasons for which one believes what one knows are consistent with the belief in question being false.