ACC - Royal Court of Justice, Bhutan

advertisement

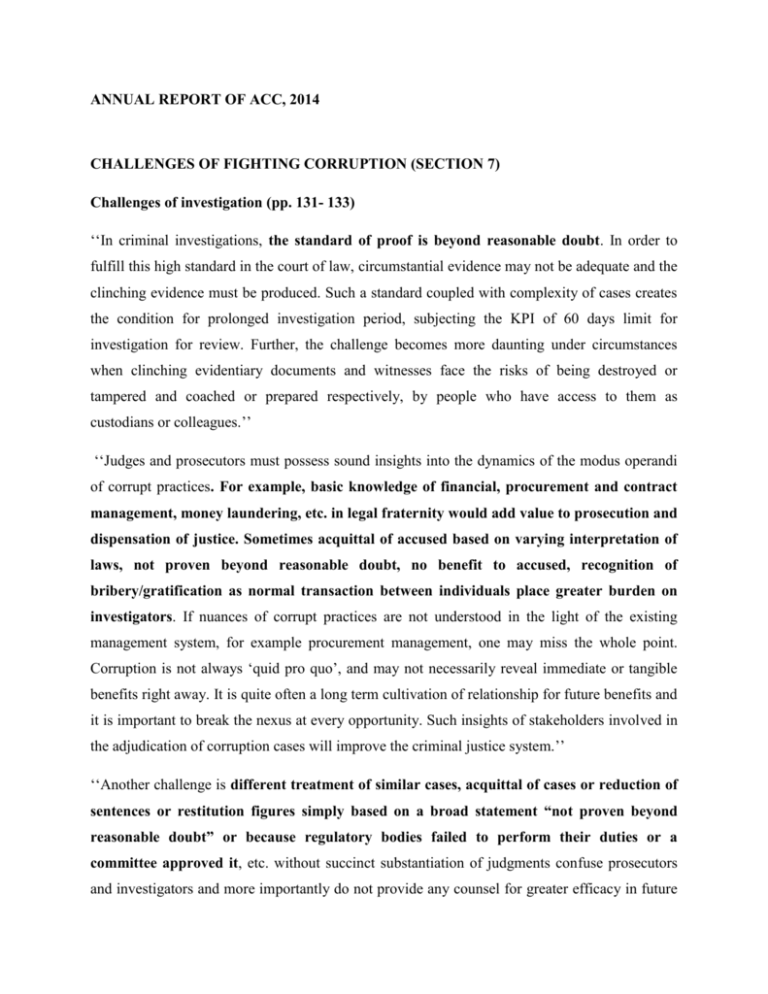

ANNUAL REPORT OF ACC, 2014 CHALLENGES OF FIGHTING CORRUPTION (SECTION 7) Challenges of investigation (pp. 131- 133) ‘‘In criminal investigations, the standard of proof is beyond reasonable doubt. In order to fulfill this high standard in the court of law, circumstantial evidence may not be adequate and the clinching evidence must be produced. Such a standard coupled with complexity of cases creates the condition for prolonged investigation period, subjecting the KPI of 60 days limit for investigation for review. Further, the challenge becomes more daunting under circumstances when clinching evidentiary documents and witnesses face the risks of being destroyed or tampered and coached or prepared respectively, by people who have access to them as custodians or colleagues.’’ ‘‘Judges and prosecutors must possess sound insights into the dynamics of the modus operandi of corrupt practices. For example, basic knowledge of financial, procurement and contract management, money laundering, etc. in legal fraternity would add value to prosecution and dispensation of justice. Sometimes acquittal of accused based on varying interpretation of laws, not proven beyond reasonable doubt, no benefit to accused, recognition of bribery/gratification as normal transaction between individuals place greater burden on investigators. If nuances of corrupt practices are not understood in the light of the existing management system, for example procurement management, one may miss the whole point. Corruption is not always ‘quid pro quo’, and may not necessarily reveal immediate or tangible benefits right away. It is quite often a long term cultivation of relationship for future benefits and it is important to break the nexus at every opportunity. Such insights of stakeholders involved in the adjudication of corruption cases will improve the criminal justice system.’’ ‘‘Another challenge is different treatment of similar cases, acquittal of cases or reduction of sentences or restitution figures simply based on a broad statement “not proven beyond reasonable doubt” or because regulatory bodies failed to perform their duties or a committee approved it, etc. without succinct substantiation of judgments confuse prosecutors and investigators and more importantly do not provide any counsel for greater efficacy in future investigations and prosecution. The same rationale will also apply to judgments of conviction for public confidence. It is apparent that strict adherence to the basic principles of presumption of innocence and burden of proof require delicate balancing of the trial procedures by the informed, impartial and independent adjudicators. The system reposes much faith in the impartiality of the adjudicators in as much as it confers on them many powers. If the traditional rule relating to burden of proof of the prosecution is allowed to be wrapped in pedantic coverage, the perpetrators of offences would be the major beneficiaries and the State and the society would be the casualty.’’ ‘‘Further, investigation into corrupt offences invariably hits institutions, agencies and their employees, directly or indirectly. The judiciary is no exception. Experience counsels that the consequences, direct or indirect for the ACC and its employees cannot be ignored. For instance, when some of the court procedures are neither clear nor standardized it can be subjected to the vagaries of the adjudicators and associated professionals; it can also become an instrument for subtle harassment to the ACC and its employees. This may not be a potential challenge now but the risk is imminent.’’ ‘‘Swift investigation followed by swift (not at the cost of justice) prosecution and adjudication form the three cornerstones of effective criminal justice system. Swift processes demand qualified investigators, prosecutors and adjudicators, both quality and number being crucial. As everyone is aware, recruitment and retention of qualified and committed professionals in the ACC and the OAG have been the biggest challenge. Besides, the perennial human resource predicament, the judiciary, ACC and the OAG may have to deliberate on making the processes more effective and efficient.’’ ‘‘A general guideline exists that a verdict should be passed within 108 days of filing a case in a court. Judgments have been passed by the courts in general fulfillment of this guideline. Delays in dispensation of justice occur due to the appeal and review system of the judiciary. Given the four-tier structure of the judiciary, cases may take minimum of three years for final judgment, if appealed right up to the Supreme. When the Army Welfare Project case was adjudicated, His Majesty commanded,“... A person guilty of corruption must be punished without fear or favor and without delay...justice must prevail always and without exception... It(corruption) will put to waste the honest labor of good citizens and set wrong example for our youth in whose hands the future of Bhutan lies... Every citizen has the right to equal and effective protection and recourse to the due process of law. But that it is also important to ensure that this sacred right is not abused in order to delay the dispensation of justice. Such delay is detrimental not only to the judicial system and the strength of law, but also to the Royal Government and the people of Bhutan’s efforts to keep Bhutan free of the scourge of corruption. Merit must be the only path to success in our country”. Some criminals are taking refuge in the procedure of the criminal justice system. Implementation of His Majesty’s Command, both in letter and spirit will result in dispensation of justice without undue delays.’’ ‘‘Judgment implementation has emerged as a serious challenge over the years. There is a general understanding that judgment must be implemented by the executive. Other than this notion, there is no clarity who should implement it. In the absence of a clear system, no one takes the lead. Agencies develop ‘cold feet’ in implementing the judgment of the courts. Enquiring on judgment implementation as a responsibility of taking the case to logical end is perceived as being vindictive. Judgment implementation at best has been done on a case by case basis in the past. Long after the judgments of the courts, restitution or recovery of proceeds of crime or administrative action still remains undone. In the final analysis, without or delayed judgment implementation, entire cycle of the criminal justice system is rendered ineffective and investigation and prosecution redundant, wasting of huge public resources.’’ 1. Standard of proof beyond reasonable doubt Article 7, Section 16, Constitution of Bhutan- A person charged with a penal offence has the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty in accordance with the law. Section 96.2, CCPC- Finding of guilt against one or more of the parties can only be given when the prosecution to the full satisfaction of the Court has established a proof beyond reasonable doubt. Section 204, CCPC- Where guilt beyond reasonable doubt has not been established to the Court’s satisfaction for the charge, the defendant shall be acquitted and released and have the conditions of his/her bail terminated. Section 202, CCPC- If following the accumulation and review of evidences, the police and the prosecutor believes that there is an insufficient legal basis to make a compelling case to prove a suspect’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, the police/prosecutor may request the Court to allow the prosecution to be withdrawn. 2. ‘‘Judges and prosecutors must possess sound insights into the dynamics of the modus operandi of corrupt practices. For example, basic knowledge of financial, procurement and contract management, money laundering, etc. in legal fraternity would add value to prosecution and dispensation of justice. Sometimes acquittal of accused based on varying interpretation of laws, not proven beyond reasonable doubt, no benefit to accused, recognition of bribery/gratification as normal transaction between individuals place greater burden on investigators.” The Court system in Bhutan till date is generic with a single judge dealing in different matters. However, few years down the line we will have specialized courts. The function of the judiciary is the interpretation of laws. Judges have functional independence. If aggrieved by the decision of a judge of the lower court, the party so aggrieved can appeal to the next higher court given the four-tier structure of the judiciary. Section 25, CCPC - A Dzongkhag Court shall exercise appellate jurisdiction over an appeal from an order, decision or judgment of Dungkhag Courts subordinate to it. Section 23, CCPC - The High Court may exercise appellate jurisdiction over: (a) any judicial review on appeal from an administrative adjudication; and (b) any order/decision/judgment of a Dzongkhag Court. Section 109, CCPC- A party to a case may file an appeal to a higher Court against a judgment of the subordinate Court. Section 110, CCPC- The Appellate Court shall: (a) determine whether there was error; and (b) if so whether such error warrants either a remand or full or partial reversal. Section 111, CCPC- The Appellate Court may: (a) dismiss the appeal; (b) reverse all or part of the Judgment awarded by the lower Court after due process of law; (c) remand the case to the lower Court with instructions; (d) order a new proceeding; or (e) charge reasonable costs to be paid by the party submitting the appeal, if the appeal is dismissed. 3. Verdict should be passed within 108 days of filing a case in a court. Section 81.2, CCPC- The Court shall convene a preliminary hearing within: (a) ten days of registration in criminal cases; Section 81.3 – 108 days (Preliminary Hearing in civil cases); Monthly case Report: A report on cases pending beyond 12 months with justification. 4. Judgment implementation: The judgment will have succinctly pronounced the implementing authority. The implementing authority should initiate the implementation of the judgment in administrative and other related cases. However, in simple monetary cases, judgment creditors should move the court for implementation of the judgment. In criminal cases, the prosecutor on behalf of the victim should initiate restitution. 5. Bail and Bond: Section 199 of the CCPC: Where a suspect other than a person accused of non-bailable offence in the Preliminary Hearing submits that he/she is not guilty and subject to the conditions stated in this Code, the Court may decide to release him/her on bail upon execution of a bond for such sum of money by one or more sureties. According to the Section 199 of the CCPC, the lone authority to send a person on bail is Court on fulfilling the conditions envisaged there under. 6. Examination of the witness: Section 78 of the CCPC - Nothing in this Code shall be deemed to authorize any person on behalf of another to address the Court or to examine witnesses, except where authorized by the Court.