Men who signed Declaration of Independence

advertisement

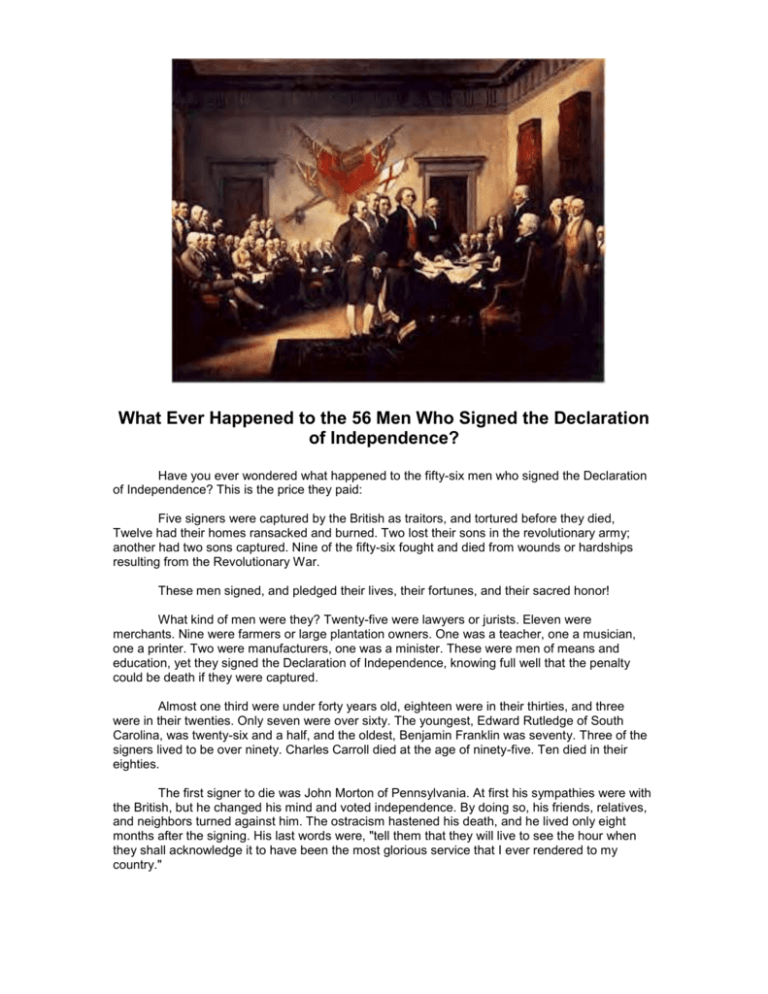

What Ever Happened to the 56 Men Who Signed the Declaration of Independence? Have you ever wondered what happened to the fifty-six men who signed the Declaration of Independence? This is the price they paid: Five signers were captured by the British as traitors, and tortured before they died, Twelve had their homes ransacked and burned. Two lost their sons in the revolutionary army; another had two sons captured. Nine of the fifty-six fought and died from wounds or hardships resulting from the Revolutionary War. These men signed, and pledged their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor! What kind of men were they? Twenty-five were lawyers or jurists. Eleven were merchants. Nine were farmers or large plantation owners. One was a teacher, one a musician, one a printer. Two were manufacturers, one was a minister. These were men of means and education, yet they signed the Declaration of Independence, knowing full well that the penalty could be death if they were captured. Almost one third were under forty years old, eighteen were in their thirties, and three were in their twenties. Only seven were over sixty. The youngest, Edward Rutledge of South Carolina, was twenty-six and a half, and the oldest, Benjamin Franklin was seventy. Three of the signers lived to be over ninety. Charles Carroll died at the age of ninety-five. Ten died in their eighties. The first signer to die was John Morton of Pennsylvania. At first his sympathies were with the British, but he changed his mind and voted independence. By doing so, his friends, relatives, and neighbors turned against him. The ostracism hastened his death, and he lived only eight months after the signing. His last words were, "tell them that they will live to see the hour when they shall acknowledge it to have been the most glorious service that I ever rendered to my country." Carter Braxton of Virginia, a wealthy planter and trader, saw his ships swept from the seas by the British navy. He sold his home and properties to pay his debts, and died in rags. Thomas Mckeam was so hounded by the British that he was forced to move his family almost constantly. He served in the Congress without pay, and his family was kept in hiding. His possessions were taken from him, and poverty was his reward. The signers were religious men, all being Protestant except Charles Carroll, who was a Roman Catholic. Over half expressed their religious faith as being Episcopalian. Others were Congregational, Presbyterian, Quaker, and Baptist. Vandals or soldiers or both looted the properties of Ellery, Clymer, Hall, Walton, Gwinnett, Heyward, Ruttledge, and Middleton. Perhaps one of the most inspiring examples of "undaunted resolution" was at the Battle of Yorktown. Thomas Nelson, Jr. was returning from Philadelphia to become Governor of Virginia and joined General Washington just outside of Yorktown. He then noted that British General Cornwallis had taken over the Nelson home for his headquarters, but that the patriot's were directing their artillery fire all over the town except for the vicinity of his own beautiful home. Nelson asked why they were not firing in that direction and the soldiers replied, "Out of respect to you, Sir." Nelson quietly urged General Washington to open fire, and stepping forward to the nearest cannon, aimed at his own house and fired. The other guns joined in, and the Nelson home was destroyed. Nelson died bankrupt, at age 51. Caesar Rodney was another signer who paid with his life. He was suffering from facial cancer, but left his sickbed at midnight and rode all night by horseback through a severe storm and arrived just in time to cast the deciding vote for his delegation in favor of independence. His doctor told him the only treatment that could help him was in Europe. He refused to go at this time of his country's crisis and it cost him his life. Francis Lewis's Long Island home was looted and gutted, his home and properties destroyed. His wife was thrown into a damp dark prison cell for two months without a bed. Health ruined, Mrs. Lewis soon died from the effects of the confinement. The Lewis's son would later die in British captivity, also. "Hones John" Hart was driven from his wife's bedside as she lay dying, when British and Hessian troops invaded New Jersey just months after he signed the Declaration. Their thirteen children fled for their lives. His fields and his gristmill were laid to waste. All winter, and for more than a year, Hart lived in forests and caves, finally returning home to find his wife dead, his children vanished and his farm destroyed. Rebuilding proved to be too great a task. A few weeks later, by the spring of 1779, John Hart was dead from exhaustion and a broken heart. Norris and Livingston suffered similar fates. Richard Stockton, a New Jersey State Supreme Court Justice, had rushed back to his estate near Princeton after signing the Declaration of Independence to find that his wife and children were living like refugees with friends. They had been betrayed by a Tory sympathizer who also revealed Stockton's own whereabouts. British troops pulled him from his bed one night, beat him and threw him in jail where he almost starved to death. When he was finally released, he went home to find his estate had been looted, his possessions burned, and his horses stolen. Judge Stockton had been so badly treated in prison that his health was ruined and he died before the war's end a broken man. His surviving family had to live the remainder of their lives off charity. William Ellery of Rhode Island, who marveled that he had seen only "undaunted resolution" in the faces of his co-signers, also had his home burned. Only days after Lewis Morris of New York signed the Declaration, British troops ravaged his 2,000 acre estate, butchered his cattle and drove his family off the land. Three of Morris' sons fought the British. When the British seized the New York houses of the wealthy Philip Livingston, he sold off everything else, and gave the money to the Revolution. He died in 1778. Arthur Middleton, Edward Rutledge and Thomas Heyward Jr. went home to South Carolina to fight. In the British invasion of the South, Heyward was wounded and all three were captured. As he rotted on a prison ship in St. Augustine, Heyward's plantation was raided, buildings burned, and his wife, who witnessed it all, died. Other Southern signers suffered the same general fate. Among the first to sign had been John Hancock, who wrote in big, bold script so George III "could read my name without spectacles and could now double his reward for 500 pounds for my head." If the cause of the revolution commands it, roared Hancock, "Burn Boston and make John Hancock a beggar!" In the face of the advancing British Army, the Continental Congress fled from Philadelphia to Baltimore on December 12, 1776. It was an especially anxious time for John Hancock, the President, as his wife had just given birth to a baby girl. Due to complications stemming from the trip to Baltimore, the child lived only a few months. Here were men who believed in a cause far beyond themselves. Such were the stories and sacrifices of the American Revolution. These were not wild eyed, rabble-rousing ruffians. They were soft-spoken men of means and education. They had security, but they valued liberty more. Standing tall, straight, and unwavering, they pledged: "For the support of this declaration, with firm reliance on the protection of the divine providence, we mutually pledge to each other, our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor." They gave you and me a free and independent America. The history books never told you a lot of what happened in the revolutionary war. We didn't just fight the British. We were British subjects at that time and we fought our own government! Perhaps you can now see why our Founding Fathers had a hatred for standing armies, and allowed through the second amendment for everyone to be armed. Would you be willing to sacrifice all for the future of your homes, your lives, your wives, and your children? America may soon need you!