Brian Wang

advertisement

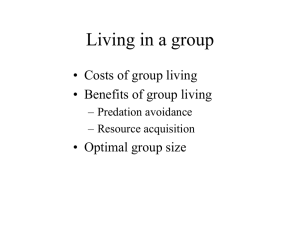

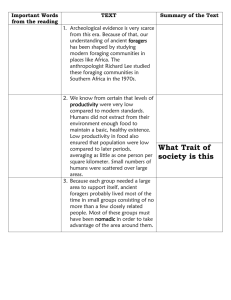

Brian R. Wang Nov. 18, 2005 Biology 112 Literary Analysis of a Classic Ecology Paper In the classic ecology paper, “Theory of Feeding Strategies”, Thomas W. Schoener examined how the specific feeding strategies of different animals influences the behaviors and morphologies of these animals in a manner that allows them to optimize the amount of food energy in their environment. Schoener believed that feeding strategies are affected by four focal aspects, which include the optimal diet, the optimal foraging space, the optimal foraging period, and the optimal foraging-group size (Schoener, 1971). By constructing the various components of the feeding strategies, Schoener produced a series of cost-benefit formulations that show how the behavioral strategies affect the overall feeding outcomes of animals. According to his research, Schoener thought that the optimal diet of an animal was a function of the caloric value of the food source, the amount of time spent searching for the food, and the handling time involved for storage or consumption of the energy source (Schoener, 1971). Using previously conducted research for the basis of his theory, he came to the conclusion that the amount of food and its caloric value is related to the size of a predator, with larger predators requiring a greater amount of food with a higher amount of energy. Also, Schoener came to the conclusion that the amount of time and energy a predator would be willing to spend on its prey increases as the nutritional value of the prey increases. Furthermore, he applied his theory to two different optimal kinds of feeders, generalists and specialist. Schoener thought that a larger animal was more likely than a smaller animal to develop into a generalist feeding pattern, due to the fact that larger animals had higher nutritional needs which could be met by obtaining a wider variety of food (Schoener, 1971). With respect to optimal foraging space, Schoener believed that the home range site of an animal increased with the body weight of the animal. Since animals of increasing size have higher average nutritional requirements, he concluded that animals with larger body weights were more willing to establish a larger foraging space in order to obtain the necessary resources for their survival (Schoener, 1971). Through a series of cost-benefit calculations, he also found that the variety of food items in a home range was more important than the overall food density. He proved this theory by referencing previously conducted research, which showed that squirrels were more likely to inhabit a territory that had a larger variety of sparsely distributed tree cones than a habitat that contained a more densely distributed amount of homogenous tree cones. Although Schoener was not able to produce a formal theory that predicted the relationship between the behavior of animals and their optimal feeding periods, he was able to make a number of assumptions based on a set of well-known animal observations. For example, he proposed that optimal feeding periods were greatly effected by climate, in a way that animals gathered for food more vivaciously during seasons that produced more profitable amounts and types of food sources (Schoener, 1971). Through his formation of the cost-benefit calculations, Schoener also discovered the three main determinates of the optimal foraging-group size: the measure of foraging efficiency, the probability of predation, and the defendable area per unit cost of defense (Schoener, 1971). After investigating several studies that looked at the different effects that foraging group-size had on feeding strategies and outcomes, he found that in most instances groups allow animals to increase their foraging efficiency and that animals participating in group foraging significantly increased their detection of predators. At the time that Thomas W. Schoener’s ecology paper “Theory of Feeding Strategies” was published, the science community had not previously focused on animal feeding behaviors in such an in-depth and comprehensive manner. Schoener’s groundbreaking theory about optimal foraging behavior opened new areas of ecological research. A couple years after “Theory of Feeding Strategies” was published, Reed Haisworth and Larry Wolf conducted research that applied of some of the principle concepts of Schoener’s study towards the feeding strategies of hummingbirds. Their research paper, entitled “Nectar Characteristics and food selection by hummingbirds”, examined how hummingbirds maximize their feeding efficiencies by choosing the nectars in their natural habitat that were highest in sugar concentration. The hummingbirds that were observed in the experimental trials consistently chose the nectars that had the highest concentrations of sucrose, even if they had to travel further distances (Haisworth and Wolf, 1976). Also, Haisworth and Wolf found that the hummingbirds were willing to spend more time extracting and consuming food from its source if it resulted in a larger nutrient pay-off. This study relates back to Schoener’s concept of the optimal diet, in which he states that individuals were more likely to expend more energy and time for food sources of higher nutritional content than they were for food sources that were at a closer location but lower nutrient value. It shows that hummingbirds were willing to incorporate feeding trade-offs into their feeding strategies in order to maximize the amount of net resources they can obtain from their surroundings. Another study that employed some of the principles of Schoener’s ecological research, “Optimal foraging in bumblebees and co-evolution with their plants”, looked at how the movements of bumblebees have co-evolved with the spatial distribution of the plants and flowers from which they use as food sources. In his analysis of bumblebee feeding strategies, Graham Pyke studied how bumblebee movement patterns were kinetically optimized in such a way that they resulted in the maximum net rate of energy gain from their food. Pyke observed how the bumblebees in his experiment used a large array of different food extraction techniques, each of which were plant specific, in order to obtain their food more efficiently, while minimizing the amount of energy they expend during the process (Pyke, 1978). He also found that the bumblebees had modified their foraging space in such a way that they had the largest variety of plants and flowers available to them for consumption. This study further examines two key aspects from “Theory of Feeding Strategies”, the optimal diet and the optimal foraging space. Pyke relates back to the concept of optimal diet by showing how bumblebees purposefully calculate their body movements in such a way that they are able to acquire the greatest amount of resources from their habitat while reducing their energy expenditure to the bear minimum. He also refers back to Schoener’s theory of optimal foraging space by exhibiting how bumblebees construct their home range site in a way that offers them the greatest variety of food resources in the smallest amount of space. The paper “Optimal foraging and community structure”, by Gary Belovsky, attempts to further the development of Schoener’s concept of the optimal diet. In his ecological investigation, Belovsky examined the relationship between the body sizes of herbivores and their specific foraging behaviors and habits. He found that herbivores maximized their nutritional intake by obtaining foods that were easy to harvest and foods that required the least amount of energy to digest (Belovsky, 1985). Also, Belovsky looked into how the body size of herbivores affected their physiological digestibility of plants. He found that body size was one of the key determinates of an herbivore’s feeding strategy, because their bodies could only physically and chemically digest a limited variety of plants in an efficient manner. The study also looked at how the existence of competition could influence the optimal foraging space of an animal. By showing that herbivores of similar physiologies were more likely to consume the same types of plants, Belovsky proposed that herbivores with comparable physiologies and similar nutritional constraints were more likely to live in territories that did not completely overlap (Belovsky, 1985). Current research in Schoener’s ecological scope of feeding strategies is directed towards a major aspect of the optimal diet theory that has been overlooked in the past. Over the past couple of decades, a lot of studies have been conducted on the strategies that foragers use to obtain immobile prey and the majority of these studies have been able to successfully apply the optimal diet theory to their specific experimental situations. But now researchers are currently interested in the application of the theory to foragers that rely on mobile prey as their sole nutritional sources. The study “Optimal diet theory: when it does work, and when and why does it fail?” published in 2001, applied the optimal diet theory to a number of different foragers whose main source of food was some type of mobile prey. The researchers found that the optimal diet theory worked very well to predict the feeding behaviors of foragers who acquired their food from stationary food sources; however they found that the theory failed to effectively predict the diet and behaviors of foragers that consume mobile prey (Christensen and Sih, 2001). The researchers discovered that one of the chief reasons why the optimal diet theory did not work well with mobile prey was because the variations of vulnerabilities in prey were more important in these instances than the behavior of the predators (Christensen and Sih, 2001). Many more questions still remain unanswered on Schoener’s “Theory of feeding strategies”. In the future, more studies should be conducted on the two less acknowledged concepts of Schoener’s theory, the optimal foraging period and the optimal foraging group-size. Even though researchers know that the optimal foraging period is somewhat influenced by the seasonality and climate of an animal’s habitat, they can investigate further into the field by examining how an animal adapts its behavior according to the changes in its environment. For example, they can observe to see if animals extend their foraging space during some seasons and decrease it during others, and they can also look to see if any changes in the food extraction techniques or kinetic body movements occur in the animals during the different seasons. With respect to the theory of the optimal foraging group-size, researchers could delve deeper into the concept by monitoring the influence of group size on animals that prey on stationary food resources, and compare this with animals that prey on mobile food. Furthermore, they could look at how disturbances and variances in the environment affect the optimum number of individuals for various groups of animal species. Works Cited Belovsky, G.E. 1985. Optimal foraging and community structure: implications for a guild of generalist grassland herbivores. Oecologia 70:35 – 52. Christensen, B. and Sih, A. 2001. Optimal diet theory: when does it work, and when and why does it fail? Animal Behaviour 62:379-390 Haisworth, R. and Wolf, L. 1976. Nectar Characteristics and food selection by hummingbirds. Oecologia 25:101 – 113. Pyke, G. 1978. Optimal foraging in bumblebees and co-evolution with their plants. Oecologia 3:281-293. Schoener, T.W. 1971. Theory of Feeding Strategies. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 2:369 – 404.