Positive Behavior Intervention Support: An Alternative to Traditional

advertisement

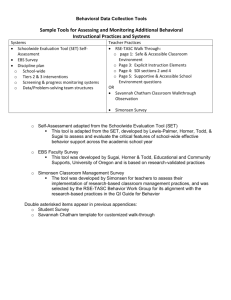

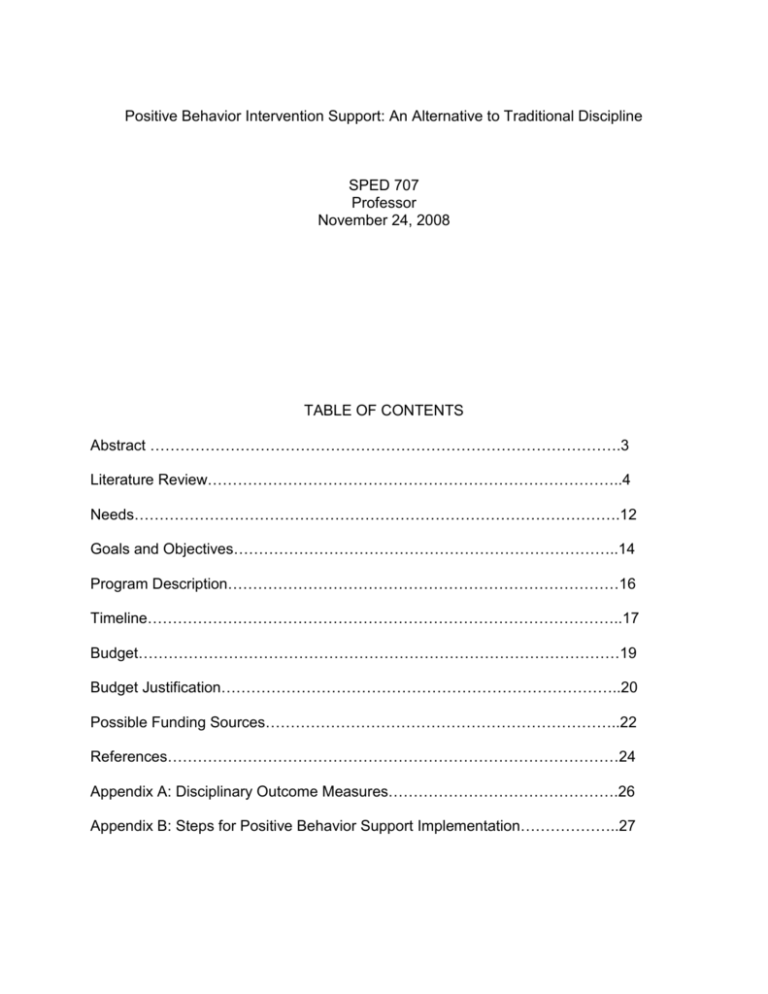

Positive Behavior Intervention Support: An Alternative to Traditional Discipline SPED 707 Professor November 24, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………….3 Literature Review………………………………………………………………………..4 Needs…………………………………………………………………………………….12 Goals and Objectives…………………………………………………………………..14 Program Description……………………………………………………………………16 Timeline…………………………………………………………………………………..17 Budget……………………………………………………………………………………19 Budget Justification……………………………………………………………………..20 Possible Funding Sources……………………………………………………………..22 References………………………………………………………………………………24 Appendix A: Disciplinary Outcome Measures……………………………………….26 Appendix B: Steps for Positive Behavior Support Implementation………………..27 2 ABSTRACT Classroom management and dealing with student behavior in the classroom continues to be an ongoing struggle for many schools and teachers. Teachers often deal with inappropriate behavior by using ineffective discipline techniques including; reactive discipline, implying punishments, aggressive behaviors such as yelling, timeouts, and other punitive measures such as office discipline referrals. Teachers continue to use such techniques in the classroom even though research has not determined their effectiveness. Some teachers expect students to behave appropriately but have not invested the time in teaching their students expected behaviors. Positive behavior support (PBS) offers an alternative to traditional discipline. PBS was originally designed to target students with developmental disabilities who would benefit from intensive behavior and social skills training. PBS was quickly adapted for the school-wide population. This approach to discipline is prevention focused and based on functional behavior analysis. PBS programs and procedures are developed on an individual basis to meet the needs of a target school. Current research supports the effectiveness of PBS in a variety of school settings. This grant proposal seeks funding for a P. S. 7, Samuel Stern School; a NYC public school that has been deemed a school in need of improvement by the Department of Education. According to the school annual accountability report school suspensions have increased from 1 in 2003-2004 to 17 in 2005-2006. This grant proposal requests funding for initial training on PBS, PBS curriculum materials and PBS support coaches as the school-wide system is implemented. 3 LITERATURE REVIEW Many teachers struggle with classroom management and discipline. Teachers continue to become frustrated, consider leaving the teaching profession, and lose instructional time. Inappropriate behaviors and discipline issues can also interrupt students’ learning. Often schools adopt discipline policies, which include punitive measures, reactive discipline and zero tolerance attitudes. There has been little research conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of these techniques, yet teachers continue to employ such measures in their classrooms (Hieneman, Dunlap, & Kincaid, 2005). Often teachers are left to decide what type of classroom management they will set up in their individual classrooms. Students do not receive the benefit of a predictable, proactive and consistent school-wide behavior management system. In a national survey given to middle and high school teachers the following statistics illustrate the impact inappropriate behavior and discipline problems can have on teachers’ attitudes and feelings about the teaching profession. Seventy-six percent of the teachers surveyed felt discipline affected their ability to teach students and one-third of the teachers surveyed had thought about leaving the teaching profession due to the amount of discipline problems they encountered (Warren, Bohanon-Edmonson, Turnbull, Sailor, Wickham, Griggs, & Beech, 2006). Positive Behavior Support is defined as a prevention-orientated approach to student discipline that is characterized by its focus on defining and teaching behavioral expectations, rewarding appropriate behaviors, continual evaluation of its effectiveness, and the integration of 4 supports for individuals, groups, the school as a whole, and school/family/community partnerships,” (Warren et al., 2006, p. 187). Positive Behavior Intervention Supports are individually designed to meet the needs of the targeted school. Even though the approach is individualized, there are key components and steps involved in implementing a Positive Behavior Support system. PBIS began as an approach to assist individuals with developmental disabilities. When the effectiveness of the approach was realized, it was quickly adapted to serve other populations. Functional Behavior Analysis provided teachers and researchers with information about the link between behaviors and the environment (Hieneman, Dunlap, & Kincaid, 2005). The use of functional behavior analysis provides teachers and school administrators with valuable information about the conditions and environments where behaviors are occurring and the consequences of the behaviors. School-wide Positive Behavior Support (SWPBS) is a tiered system, which provides varying levels of support given the needs of the target population. Positive Behavior Support is used school-wide, in specific non-classroom settings such as hallways, cafeterias, and playgrounds, in specific classrooms and with individual students (Oswald, Safran, & Johanson, 2005). The primary tier is aimed at teaching all students behavioral expectations in an attempt to prevent problem behaviors from occurring (Sugai & Horner, 2006). The primary tier targets the entire student population and is successful with 80-90% of the students. The goals of primary prevention include universal prevention for the entire school, maximizing achievement, deterring problem behaviors and increasing positive peer and adult interactions (Muscott, Mann, & LeBrun, 2008). 5 The secondary tier is aimed at reaching a small number of students who need additional support to be socially successful at school. Students targeted for secondary tier interventions may be at risk for developing problem behaviors (Sugai & Horner, 2006). Five to ten percent of the student population requires secondary tier interventions. The goals of the secondary tier include reducing opportunities where behaviors are fostered and teaching skills which increase a student’s responsiveness to primary tier interventions (Muscott, Mann, & LeBrun, 2008). The tertiary tier is aimed at assisting students with high-risk behaviors through the use of specialized behavior intervention plans. Personnel working with students at the tertiary level have received specialized training and are often school psychologists and special educators (Sugai & Horner, 2006). One to five percent of the student population requires tertiary tier interventions. The goals of tertiary tier interventions are to reduce the frequency, complexity and intensity of problem behaviors and to provide alternative replacement behaviors (Muscott, Mann, & LeBrun, 2008). Positive Behavior Support (PBS) is systematically implemented in a target school using four key components. First, a school develops a team of school personnel who will serve as a committee to develop measurable goals and outcomes. The committee looks at data collected on current discipline policies and develops a plan to target problem areas within the school. Next, the team and school identify practices they will use to implement PBS (Sugai & Horner, 2006). The team typically consists of administrators, general and special education teachers, school psychologist or another person with behavior and mental health expertise, paraprofessionals and community members (Muscott, Mann, & LeBrun, 2008). After developing school-wide practices to 6 implement, the school uses the data collected to inform their decision making and justify the need for change. Last, the school develops systems to support the implementation of PBS in their school. These four components interact and guide each other to support staff behaviors, student behaviors, decision making and social competence and academic achievement (Sugai & Horner, 2006). PBS contains the following elements; defining and teaching behavioral expectations, rewarding appropriate behaviors, continual evaluation of the program’s effectiveness, and integration of support from schools, families and the larger community (Warren, et al., 2006). All of the components and elements need to be in place for the implementation of Positive Behavior Support to be successful. Positive Behavior Intervention Support (PBIS) is currently being used in thousands of schools across the United States (Bradshaw, Reinke, Brown, Bevans, & Leaf, 2008). Current research has shown Positive Behavior Intervention Support to be effective in a wide range of school settings, as well as with a wide range of student populations. Positive Behavior Intervention Support provides schools with an alternative to traditional classroom discipline, which is often punitive and reactive. Warren et al. (2006) conducted a study on the effectiveness of PBS in an urban middle school. Previous research was somewhat limited and the focus had been on evaluating the use of PBS in suburban schools serving middle class students. A threeyear study was conducted in a middle school serving 737 students in grades 6-8. The community where the school was located was faced with the challenges of poverty, crime and limited social resources. The school was interested in decreasing the number of discipline problems. Eighty-one percent of the students received at least one 7 discipline referral per year and forty-two percent of the students received at least five discipline referrals per year. During the first year of PBS implementation, trainers and support coaches established a rapport with the school faculty and administration. During the second year of the study, PBS was implemented school-wide. The school developed five behavioral expectations, called Steps to Success. Students were taught the five expectations and then recognized for displaying positive behaviors. Students were given coupons, which could be used to enter special drawings. During one year of implementation, researchers collected data, which demonstrated the effectiveness of PBS. The number of discipline referrals is typically used to measure the effectiveness of PBS. At the end of year two a decrease in the following measures was noted; office referrals, in-school conferences, time-outs, in-school suspensions and short-term (out of school) suspensions (Warren et al., 2006). See Appendix A. In 2002, New Hampshire implemented a statewide Positive Behavior Intervention Support system. The goal was to find an alternative to the traditional reactive and punitive discipline measures being used in New Hampshire schools. The interventions were designed based on the OSEP Center on Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports model. School-wide Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports were implemented in 124 private and public preschools and K-12 schools throughout New Hampshire. The fidelity of the program was assessed using the School-wide Evaluation Tool (SET). The 22 schools in cohort 1 collectively decreased the number of office discipline referrals, in-school suspensions and out-of-school suspensions. After the implementation of School-wide Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports system teachers and administrators also noted time savings in the areas of teaching time, 8 learning time and leadership time, which correlates with the decrease in the number of office discipline referrals, in-school suspensions and out-of-school suspensions. Improvements were also noted in the reading and math state assessments (Muscott, Mann, & LeBrun, 2008). Bradshaw et al. (2008) conducted a randomized study of the use of Positive Behavior Intervention and Supports (PBIS) in 37 elementary schools in Maryland. Bradshaw et al. (2008) hypothesized that it was likely some schools implement aspects of PBIS without having received formal training in PBIS procedures. The elementary schools were randomly assigned to either the control group or intervention group after being matched on demographics. The intervention group received assistance creating an internal PBIS team, a two-day summer training conducted by the developers of PBIS, support from local behavior coaches trained in PBIS, and an annual summer booster training course. The fidelity of the PBIS implementation was measured using the School-wide Evaluation Tool (SET), which yields information based on seven subscales. The subscales mentioned include; overall SET, defining expectations, teaching expectations, reward system, response to behavioral violations, monitoring and evaluation, and management and district support. Schools in both the control and intervention groups exhibited high levels of responding to behavioral violations and low levels of teaching and defining behavioral expectations before the implementation of PBIS. These findings are consistent with traditional reactive and punitive discipline policies and support the need for reform in the area of school discipline and approaches to managing behaviors (Bradshaw et al., 2008). At the conclusion of the study, Bradshaw et al. (2008) found that schools in the intervention group were able to 9 implement PBIS with high fidelity within one to two years. Schools in the intervention group outperformed the schools in the control group in six of the seven subscales (Bradshaw et al., 2008). This study illustrates the importance of implementing all components of PBIS. Stormont, Covington Smith and Lewis (2007) conducted a study in a head start setting to evaluate the effectiveness of using precorrection and praise statements. The researchers were interested in determining if a correlation existed between an increase in positive teacher behaviors and a decrease in students’ problem behaviors. Precorrection was defined as specific prompts for desired behaviors in a specific setting. Praise was defined as behavior specific verbal feedback. The researchers chose participants for the study who met the criteria of using more reprimands than praise in their classrooms. Researchers used a Teacher Behavior Observation Form to collect data for three behavior categories; specific behavior praise, precorrections and reprimands. The participants in the study received training in Positive Behavior Support during a two-day workshop and two in-services during the year. Each of the teachers were able to reduce the rate of problem behavior during small group instruction through the use of precorrection and praise (Stormont, Covington Smith, & Lewis, 2007). Frazen and Kamps (2008) conducted a study to evaluate the effectiveness of Positive Behavior Support when used in a playground setting. The school setting was an urban charter elementary school serving children in grades K-6. Before this study began, the charter school had implemented a School-wide Positive Behavior Support system. Ten teachers at the school received training in the recess intervention, which included teachers changing their supervision behaviors as well as teaching playground 10 expectations to the students. There was a token reward system for students who displayed appropriate behaviors while playing on the playground. Target behaviors were operationally defined before data collection began. Follow-up meetings were used to discuss data collected and provide teachers with feedback and encouragement. The use of the playground intervention as a component of the School-wide Positive Behavior Support system was found to increase teachers’ active supervision and decrease students’ problem behaviors (Frazen & Kamps, 2008). This study illustrates the effectiveness of Positive Behavior Supports in non-academic settings and the need for teachers to actively modify their behaviors. In a study conducted by Oswald, Safran and Johanson (2005), the use of Positive Behavior Support was found to be effective during a five-week intervention during which rural middle school students were taught behavioral expectations for school hallways. The components of the intervention included active supervision, positive practice, discussion with students, pre-correction, verbal praise, reinforcement and correction of inappropriate behaviors. Teachers reviewed behavioral expectations during homeroom, were visible during hallway transition and used catch’em being good tickets to recognize students displaying appropriate behaviors (Oswald, Safran, & Johanson, 2005). It is important for students to be taught behavioral expectations prior to being asked to display appropriate behaviors. Positive Behavior Support is a system that provides schools with tools to create an individualized plan to help students learn appropriate behavioral expectations in a proactive, prevention-focused and consistent way. Positive Behavior Support provides schools with a way to teach all students appropriate 11 behaviors, including students that are at-risk for developing problem behaviors and those students who have been identified as exhibiting patterns of problem behavior. NEEDS Many schools rely heavily on reactive and punitive discipline as a means of dealing with challenging and disruptive behaviors. Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBS and PBIS) have been shown to be effective in a variety of school settings. Students benefit when behavioral expectations have been phrased positively, are consistent school-wide, are taught explicitly and appropriate behaviors are reinforced. When teachers graduate with their undergraduate degree in education and begin teaching, many still feel they lack adequate training and education in classroom management. Positive Behavior Support provides teachers and schools a validated, structured approach to classroom management. P.S. 7, Samuel Stern School, is currently classified, by the New York City Department of Education, as a School in Need of Improvement (SINI). Schools are classified as SINI if they have not met Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) on the same accountability measure for two consecutive years while receiving Title 1 funds. P.S. 7 is located in Manhattan, District 4, and serves students in grades pre-kindergarten through eighth grade. Sixty-two percent of the students at P.S. 7 are Hispanic or Latino, 35% are African American and 2% are White. Ninety percent of the student population is eligible for free lunch program. When reviewing the annual school report card (2006-2007) P.S. 7, provided by the NYC Department of Education, the following statistic was noted; school suspensions increased from 1 in 2003-2004 to 17 in 2005-2006. School suspensions are one measure of the effectiveness of a school-wide discipline policy. Based on the 2006- 12 2007 annual school report card, 13% of teachers at P. S. 7 are teaching without a valid teaching certificate and 15% of teachers are teaching outside their certification area. Schools are required by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) to use positive behavior interventions and supports in the development, review or revision of Individualized Education Plans (IEP) of students whose behavior impedes the student’s learning or the learning of others (Warren et al., 2006). Positive Behavior Supports provide a systematic way for schools to teach all students appropriate behaviors. When students are taught appropriate behaviors, they experience more social success in school. An increased feeling of success in the social aspects of school can boost students’ self-confidence and improve their quality of life. Social skills and appropriate behavior are essential to being a fully and participating member of a school and community. The administration and faculty at P.S. 7 have identified the need for an alternative to the current discipline policy, which has resulted in an increased number of school suspensions. P.S. 7 has demonstrated an interest and commitment to the development of a Positive Behavior Support system. 13 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES Peshak George, Harrower and Knoster (2003) outline the six general steps for development and implementation of School-wide Positive Behavior Support. These steps are: “establish a foundation for collaboration/operation, building faculty involvement, establishing a data-based design making system, brainstorming and selecting strategies within an action planning process, implementing school-wide program through an action plan, and monitoring, evaluating and modifying the program,” (p.171). See Appendix B for more detailed information. These general steps will be used as a reference as P.S. 7 implements a Positive Behavior Support system in the school. Goal 1: P.S. 7 will acquire a commitment from 80% of the administration and faculty Conduct a survey to determine interest and commitment (survey will be given to all administration, faculty and support staff) Goal 2: P. S. 7 will implement Positive Behavior Support with 80% fidelity in 2 years Develop a planning team Attend one-day workshop on the basics of Positive Behavior Support Collect data on current discipline policies Create an implementation plan Develop 3-5 positive behavioral expectations to be used school wide Develop lesson plans for teacher use Collect data monthly on discipline Evaluate effectiveness of PBS using data collected 14 District 75 personnel (local behavioral support coaches) will provide ongoing support during the development and implementation of Positive Behavior Supports Goal 3: Students will decrease level of inappropriate behavior Teach school-wide behavioral expectation to all students Create secondary support plans for students with at-risk behaviors who have not responded to primary supports Create tertiary support plans for students who have been identified as have patterns of problem behavior 15 PROGRAM DESCRIPTION Participants: Entire student population of P.S. 7, 419 students in pre-kindergarten-eighth grade will benefit from the implementation of School-wide Positive Behavior Support. Staff: An internal Positive Behavior Support team developed by the administration and staff at P.S. 7 will be responsible for the development and implementation of PBS with the support of local behavior coaches from District 75 and the NYC Positive Behavior Intervention and Supports Office. The PBS team will consist of the principal, school psychologist, 3 general education teachers, 2 special education teachers, 1 paraprofessional, 1 person from the support staff, 1 parent and 1 community member. Overview: Funding secured will be used to provide the PBS team at P.S. 7 the opportunity to attend a one-day workshop on the basics of Positive Behavior Support, purchase curriculum materials and receive monthly assistance from local behavior coaches. The workshop will provide the PBS team with background information on the foundations of School-wide Positive Behavior Support, developing classroom routines and student expectations and the chancellor’s regulations. Positive Behavior Support curriculum materials will provide the PBS team with information to begin the development of their own individualized program. The support from local behavior coaches will assist the PBS team in the development and implementation the program. 16 TIMELINE January 2009 Obtain support and commitment from administration and faculty Attend one-day workshop on the basics of Positive Behavior Support Purchase Positive Behavior Support curriculum materials February 2009 Create implementation team Conduct self-study assessment Collect data on current discipline policies Develop a monthly meeting schedule (internal PBS team and local coaches) March 2009-August 2009 Create an implementation plan Develop 3-5 positive behavioral expectations to be used school wide Develop lesson plans for teacher use Design a data collection system September 2009 Teach behavioral expectation to students October 2009 Begin collecting data on discipline on a monthly basis January 2009 Evaluate effectiveness of PBS using data collected Assess the need for continued support of local positive behavior coaches Assess the need for development of secondary and tertiary supports 17 February 2009 Develop necessary secondary and tertiary supports August 2009 Assess fidelity of year 1 implementation Begin discussing development of non-academic setting PBS 18 BUDGET Foundations of Positive Behavior Interventions and Support Workshop (Initial Training provided by District 75 professional development) Positive Behavior Support Curriculum Materials Monthly support meeting with local behavior coaches Support from STOPP program to develop secondary and tertiary supports for individual students Total: $550.00 $743.90 $600.00 $900.00 $2793.90 19 BUDGET JUSTIFICATION Sugai and Horner (2006) noted that ”stable and recurring funding should be secured to support the SWPBS coordinator and activities specified in the annual action plan,” (p. 251). Foundations of Positive Behavior Interventions and Support Workshop (PBIS) Provided by Provided by District 75 Office of Professional Development Trainer: Satish Moorthy Course Description: a full-day workshop which includes: understanding major handicapping conditions affecting D75 students; school-wide PBS; developing classroom routines and student expectations; strategies to prevent counter aggression; chancellor’s regulations on child abuse, corporal punishment, and verbal abuse; and the fundamentals of functional behavior assessment. Total: x11 $50.00 $550.00 Positive Behavior Support Curriculum Materials Purchased from American Association of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (www.aamr.org) Supervisory Edition for Training Supervisors Supervisor Trainee Resource Guide Direct Support Edition for Training Direct Support Professionals Direct Support Trainee Resource Guide Shipping and Handling Total: x1 x1 x1 x1 x1 $395.00 $10.95 $295.00 $7.95 $35.00 $743.90 Monthly Support from local behavior coaches Provided by District 75 Office of Positive Behavior Intervention and Supports Description: To provide “hands-on” assistance to schools x6 $100.00 requesting help to identify and resolve situations. Team months members from District 75 will follow-up on plan development and implementation with your school staff at the cost of $100 per day. Total: $600.00 20 Support from STOPP Program STOPP (Strategies, Techniques and Options Prior to Placement) Provided by: Dana Ashley, District 75 Course Description: To provide “hands-on” assistance to Package $900.00 schools requesting help to identify and resolve situations 1: 2 full occurring due to a recent escalation of challenging behaviors days + by an individual student. The STOPP team will provide one halfsupport to help schools build capacity and resolve concerns, day as well as make recommendations for the development of a intervention plan. The goal of STOPP is to educate students who exhibit challenging behaviors in the least restrictive environment possible. A District 75 clinician trained in Positive Behavior Supports will come to the school to help assess the situation and then assist your school team to develop and implement an action plan. The consultation meeting is free. Total: $900.00 21 POSSIBLE FUNDING SOURCES Adco Foundation, Inc. 666 Broadway, 10th Fl. New York, NY 10012-2317 Telephone: (212) 674-7105 Contact: Dana Davis, Exec. Dir. Additional info: FAX: (212) 674-7100 E-mail: adcofoundation@yahoo.com Tel. for application information: (646) 602-5623 Types of Support: Conferences/seminars, Continuing support, Curriculum development, General/operating support, Program development, Research, and Seed money Carnegie Corporation of New York 437 Madison Ave. New York, NY 10022-7003 Telephone: (212) 371-3200 Contact: Rikard Treiber, Assoc. Corp. Secy. and Dir., Grants Management Fax: (212) 754-4073 URL: www.carnegie.org Types of Support: Conferences/seminars, Continuing support, Curriculum development, Employee matching gifts, General/operating support, Program development, Program evaluation, Publication, Research and Technical assistance The Heckscher Foundation for Children 123 E. 70th St. New York, NY 10021-5006 Telephone: (212) 744-0190 Contact: Virginia Sloane, Pres.; Julia Bator, Sr. Prog. Off. Fax: (212) 744-2761 URL: www.heckscherfoundation.org Types of Support: Building/renovation, Curriculum development, Equipment, Fellowships, Internship funds, Matching/challenge support, Program development, Program evaluation, Research, Scholarship funds and Seed money 22 The Achelis Foundation 767 3rd Ave., 4th Fl. New York, NY 10017-9029 Telephone: (212) 644-0322 Contact: John B. Krieger, Secy., Exec. Dir. and Asst. Treas. Fax: (212) 759-6510 E-mail: main@achelis-bodman-fnds.org URL: http://foundationcenter.org/grantmaker/achelis-bodman/ Types of support: Conferences/seminars, Curriculum development, Equipment, General/operating support, Matching/challenge support, Program development, Program evaluation, Publication, Research, Scholarship funds, Seed money and Technical assistance 23 REFERENCES Bradshaw, C. P., Reinke, W. M., Brown, L. D., Bevans, K. B., & Leaf, P. J. (2008) Implementation of School-Wide Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS) in Elementary Schools: Observations from a Randomized Trial. Education and Treatment of Children, 31(1), 1-26. Carr, E. G., (2007) The Expanding Vision of Positive Behavior Support: Research Perspectives on Happiness, Helpfulness, Hopefulness. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 9(1), 3-14. Frazen, K. & Kamps, D. (2008) The Utilization and Effects of Positive Behavior Support Strategies on an Urban School Playground. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 10(3), 150-161. George, H. P., Harrower, J. K., & Knoster, T. (2003) School-Wide Prevention and Early Intervention: A Process for Establishing a System for School-Wide Behavior Support. Preventing School Failure, 47(4), 170-176. Hieneman, M., Dunlap, G., & Kincaid, D. (2005) Positive Support Strategies for Students with Behavioral Disorders in General Education Settings. Psychology in Schools, 42(8), 779-794. Kincaid, D., George, H. P., & Childs, K. (2006) Review of Positive Behavior Support Training Curriculum: Supervisory and Direct Support Editions. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 8(3), 183-188. Lewis, R. (2001) Classroom discipline and student responsibility: the students’ view. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17, 307-319. Muscott, H. S., Mann, E. L., & LeBrun, M. R. (2008) Effects of Large-Scale 24 Implementation of Schoolwide Positive Behavior Support on Student Discipline and Academic Achievement. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 10(3), 190-205. Oswald, K., Safran, S., & Johanson, G. (2005) Preventing Trouble: Making Schools Safer Places Using Positive Behavior Supports. Education and Treatment of Children, 28(3), 265-278. Stormont, M. A., Covington-Smith, S., & Lewis, T. J. (2007) Teacher implementation of precorrection and praise statements in Head Start classrooms as a component of a program-wide system of positive behavior support. Journal of Behavioral Education, 16, 280-290. Sugai, G., & Horner, R. R. (2006) A Promising Approach for Expanding and Sustaining School-Wide Positive Behavior Support. School Psychology Review, 35(2), 245259. Warren, J. S., Bohanon-Edmonson, H. M., Turnbull, A. P., Sailor, W., Wickman, D., Griggs, P., & Beech. S. E. (2006) School-wide Positive Behavior Support: Addressing Behavior Problems that Impede Student Learning. Educational Psychology Review, 18(2), 187-198. 25 APPENDIX A Disciplinary Outcome Measures (Warren et al., 2006) 26 APPENDIX B Steps for Positive Behavior Support Implementation (Peshak George, Harrower, & Knoster, 2003, p.172-174) TABLE 2. Step 1: Establish a Foundation for Collaboration or Operation Legend for Chart: A - Essential components B - Yes C - Some D - No E - Unsure A B C D E 1-1. A school improvement plan exists that includes goals, objectives, and activities for improving student behavior. 1-2. A school improvement team is aligned with the school mission statement. 1-3. All faculty, staff, and administration are familiar with the school mission statement and the goals and objectives of the school improvement plan. 1-4. A school-based positive behavior support (PBS) team has broad representation including some school improvement team members. 1-5. Administrators are active participants/ leaders on PBS team. 1-6. A behavior specialist or team member with behavioral expertise plays an active role on the PBS team. 1-7. A school-based PBS team meets at least once a month. TABLE 3. Step 2: Build Faculty Involvement Legend for Chart: A - Essential components B - Yes C - Some D - No E - Unsure A 2-8. At least 80% of your faculty, staff, and administration are committed to decreasing problem behaviors across students. 2-9. At least 80% of your faculty, staff, and administration are B C D E 27 committed to increasing the academic performance of students. 2-10. All faculty are familiar with the behavior problems occurring across campus. 2-11. At least 80% of faculty, staff, and administration have been trained in basic behavioral principles. 2-12 Behavior problems are addressed quickly and effectively across all settings. TABLE 4. Step 3: Establish a Data-Based Decision-Making System Legend for Chart: A - Essential components B - Yes C - Some D - No E - Unsure A B C D E 3-13. A school-wide data collected collection system exists to track the number of all discipline incidents occurring across campus. 3-14. Data collected are meaningful (functional) to administration, faculty, and staff. 3-15. School-wide data collected are entered into the system weekly. 3-16. School-wide data collected are analyzed at least once a month by PBS team. 3-17. Date collected guide ongoing-decision-making procedures on campus. 3-18. Problem behaviors are defined clearly. 3-19. School uses an office discipline referral form for problem behavior. 3-20. An office discipline referral process exists at your school. 3-21. Major (i.e., office referral) discipline incidents are defined and familiar to faculty, staff, and administration. 3-22. Minor (i.e., classroom managed 28 problems) discipline incidents are defined and familiar to faculty, staff, and administration. TABLE 5. Step 4: Brainstorm and Select Strategies Within an Action Planning Process Legend for Chart: A - Essential components B - Yes C - Some D - No E - Unsure A B C D E 4-23. An array of strategies or supports are available for faculty and staff to effectively and efficiently address problem behavior so that classroom instruction can continue. 4-24. Procedures to address emergency/ dangerous situations at individual and school-wide levels are in place and students, faculty, staff, and administration are trained. 4-25. A continuum of consequence procedures is defined clearly and used regularly. 4-26. Positively stated (3-5) student expectations are defined clearly. 4-27. Rules for school-wide expectations are addressed across all settings. 4-28. Lesson plans to teach student expectations are developed. 4-29. School-wide reward/recognition system is developed. TABLE 6. Step 5: Implement School-Wide Program Through an Action Plan Legend for Chart: A - Essential components B - Yes C - Some D - No E - Unsure A B C D E 5-30. All administration, faculty, and 29 staff are trained on school-wide procedures (i.e., consequences for appropriate and problem behavior, student expectations, rewards, and tracking system to monitor success). 5-31. Formal strategies exist to involve families in the PBS school-wide program. 5-32. Team has a budget for (a) teaching students, (b) ongoing rewards, and (c) annual faculty planning. 5.33. All faculty and staff are directly involved in the implementation of school-wide interventions. 5-34. Expected student behaviors are taught directly to students. 5-35. Display of expected student behaviors are rewarded/acknowledged regularly (systematically "catch them being good"). 5-36. Supervisors actively supervise (i.e., move, scan, and interact) students across campus (including nonclassroom settings). 5-37. Physical/architectural features are modified to limit (a) unsupervised settings, (b) unclear traffic patterns, and (c) inappropriate access to and from school grounds. 5-38. Scheduling of student movement ensures appropriate numbers of students across campus (including nonclassroom settings). TABLE 7. Step 6: Monitor, Evaluate, and Modify the Program Legend for Chart: A - Essential components B - Yes C - Some D - No E - Unsure A B C D 6-39. At least 80% of students respond predictably and successfully to your school-wide system of behavior support. 6-40. Ongoing (i.e., throughout the school year) decision-making procedures are based on the school-wide data collected. 6-41. Results of school-wide analyses E 30 (i.e., current status of behavior patterns) are included in all faculty meetings. 6-42. Booster training activities for students are developed, modified, and implemented based on the school data. 6-43. Booster training activities for faculty, staff, and administration are developed, modified, and implemented based on the school data. 6.44. The school-wide collection system emphasizes the number of positive/ expected behaviors rewarded/acknowledged rather than problem behaviors. SPED 707 GRANT PROPOSAL Rubric for Part 2: Written Document Author of Grant: Nicole B. Intervention Supports Does not meet standard (Far below standard) (1) 1. One page abstract clearly synthesized description and purpose of proposed project (x1) 2. Review of literature from primary sources ICC9S2 (x2) 3. Literature review supported theory Teacher candidate’s onepage abstract did not provide goals, purpose, or description of the proposed project. TC’s abstract exceeded one page. -The teacher candidate’s review of the literature did not contain a cross section of primary refereed sources published within the past 5 years. - TC’s sources were tangential to the topic or are not regarded as nonauthoritative. - Only one or two sources used by the TC. The teacher candidate’s support for the theory underlying the Title of Grant: Positive Behavior Does not meet standard (Emerging or marginal) (1) Meets Standard (2) Above Standard (3) Teacher candidate provided a onepage abstract with minimal or superficial and/or vague goals, purpose & description of proposed project. The teacher candidate’s review of the literature was generally from primary resources & included no more than two secondary references. - The TC’s review contained three different refereed journal titles regarded as authoritative to the topic being reviewed. - No more than two of the TC’s references were published prior to the last five years. The teacher candidate’s review supported the theory behind Teacher candidate provided a onepage abstract with satisfactory goals, purpose, and description of proposed project. Teacher candidate provided a onepage abstract that clearly synthesized goals, purpose, & description of proposed project. X The teacher candidate provided a review of the literature that include one secondary reference. - The TC’s review contained four different refereed journals regarded as authoritative to the topic being reviewed. - More than one of the TC’s references were published prior to the last 5 years. The teacher candidate provided a review of the literature that contained only primary resources & included applicable statistics. X - The TC’s review was made from at least five different refereed journals regarded as authoritative to the topic. X -All of the TC’s references were published within last 5 years except for seminal/highly important original sources. X The teacher candidate’s literature review supported the theory The teacher candidate’s literature review supported the theory behind the 32 (x2) 4. Needs section was comprehensive need for the development of a grant was not clear or not supported by current literature. - The TC provided no systematic development in support for the value of the project. the need for the project, but no data were provided to support the need for the proposed interventions. - The TC presented no statistical data to show the demand for such a proposed project. underlying the need for the project. -With a link between the literature and statistical data from a reliable source, the TC demonstrated the need for the suggested project. -The connection made by the TC was not fully clear, but rather was somewhat tangential to the project. need for the project, & a clear link was established between the statistics & the need for the project. X -The theory was developed in an orderly and wellrelated manner. X The teacher candidate’s needs section failed to identify the specific needs of the school or agency. The teacher candidate’s needs section provided minimal information on the requesting school agency or source. However, it was unclear as to why the proposal is necessary for this site. The teacher candidate’s goals & objectives of the proposed project were stated, but were only tangentially related to the need for the project. The teacher candidate’s needs section provided satisfactory information about the requesting school agency or source and identified why this proposal is deserving funding. The teacher candidate’s needs section provided comprehensive information about the requesting school, agency or source & identified why this proposal is deserving of funding. X The teacher candidate’s goals & objectives of the proposed project were clearly related to the established need for the program. - The TC’s goals and The teacher candidate’s goals & objectives were a clear outgrowth of the stated need for the project, and strongly link the need with the activities of the proposed program. Objectives were specific and measurable. X (x2) 5. Goals and objectives were outgrowth of needs (x2) The teacher candidate’s goals & objectives of the proposed program were not presented or showed no clear relationship to the stated need of the program. 33 6. Timelines and Responsibilities (x1) 7. Support staff and resources (x1) 8. Budget and Budget justification objectives were a clear outgrowth of the stated need. The teacher candidate’s proposed program clearly outlined a format and timeline of the program sessions and the role of all participants. The teacher candidate’s proposed program did not clearly establish a timeline or format for planned activities (workshops, sessions, start, etc.). - The TC failed to establish primary responsibilities for activities or the method of evaluating the outcomes of interventions. -The teacher candidate provided no explanation (or an incomplete one) of the resources & staff necessary to carry out the proposed project. - Staff qualifications were not identified by the TC. The teacher candidate’s proposed program established a timeline, the format of interventions, and activities and their content. The teacher candidate’s proposed program contained a comprehensive format including descriptive & realistic content, timeline, activities and interventions. -The teacher candidate provided a general description of materials & staff involved in the project with a limited explanation of specific responsibilities & qualifications of staff. The teacher candidate provided a systematic presentation of staff & their responsibilities & qualifications. -Sources of materials & their purposes in the program were specified by the TC. The teacher candidate provided a thorough presentation of staff & their responsibilities & qualifications, as well as the agency or professional association providing their services (“matching fund sources”). X -Sources of materials & curriculum were identified by the TC. X The teacher candidate provided no The teacher candidate provided a The teacher candidate provided a -The teacher candidate provided a precise budget & X - It specifically delineated the role of participants, and methods/measures for evaluating outcomes. X -Staff responsibilities were vaguely described by the TC. 34 (x1) 10. APA writing style format & writing mechanics (x1) 11. On time submission was written in fluent and organized manner (x2) budget for the proposed program. - No budget justification was provided by the TC. - The TC’s budget for project operation was presented without justification &/or line item explanation. Teacher candidate’s use of APA writing style was absent from the literature review, and/or improper citation, preparation of reference section, tables, and/or appendices was evident. Numerous grammatical &/or spelling errors were present. The teacher candidate’s paper was more than one week late. - The TC’s writing was unclear and/or unprofessional. -Little attention appears to have been given to the requirements of the project by the TC. -Some sections budget & justification devoid of a delineation of staff experience & training that justifies their role & level of remuneration. budget & justification with line item delineation of staff participant’s experience & training, thereby supporting their role & level of remuneration. justification with line item delineation, thereby supporting their role & level of remuneration. Matching fund items & sources were delineated. X Teacher candidate’s use of APA style showed signs of emerging, but inconsistently utilized. -The TC’s proposal contained five or more grammatical &/or spelling errors. Teacher candidate’s use of APA style was present throughout the paper. -The TC’s proposal contained no more than four grammatical &/or spelling errors. Teacher candidate’s use of APA style was consistently evident and correct throughout the paper. X - The TC’s proposal contained fewer than three spelling or grammatical errors. X The teacher candidate’s paper is 1 to 7 days late. -The TC’s writing sometimes rambled off the topic or was confusing to the reader. - The TC minimally followed the rules of format. Teacher candidate’s writing was reasonably clear and fluent, with logical sequencing of content. - The TC provided a Table of Contents & followed the rules of format including subheadings, page numbers, Teacher candidate’s writing was clear, fluent, well-developed & sharply focused. X - The TC provided a Table of Contents, appropriate subheadings, and evidenced strong attention to page format, including page numbers, margins, appropriate page breaks, & double 35 of the TC’s grant proposal were missing. margins, appropriate page breaks, citation, & double-spacing. Score for Grant Proposal Document: _____ of 45 (professionalism) = _56.5_ of 57 spacing. X and _____ of 12 _99_ of 100 X 3 = _297 of 300 possible points for grant proposal (written) Additional comments: A fine paper: Well written in content, organization and mechanics. Well presented. Easily read by the reviewer. Reflects great planning, research, effort, and skill.