Columbia Readings - 2005 - Department of Civil Engineering

advertisement

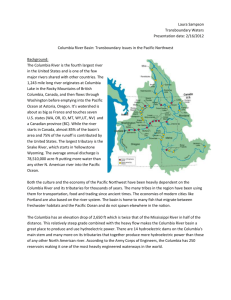

Figure 1: Dams if the Columbia River Basin. (United States Army Corps of Engineers) A Brief Introduction: The Columbia River Basin is North Americas 4th largest river basin. (United States Army Corps of Engineers) It extends from its headwaters in Canada and throughout the Pacific Northwest resulting in a drainage area of about 260,000 square miles, 15% of the drainage area and 25% of the runoff volume is attributes to Canada. (United States Geological Survey) The Columbia arises from Lake Columbia in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia and travels 1,270 miles to the Pacific Ocean. With an average annual discharge of 78,510,000 acre-feet, it pours more water into the Pacific than any other river in the Americas. The river’s elevation change is 2650 ft, a drop twice that of the Mississippi, and in half the distance. There are 4 major tributaries to the Columbia: the Kootenai and Flathead/Pend Oreille rivers, the Snake River, and the Willamette River. The Snake is considered the main tributary and starts in Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming before traveling some 1038 miles before joining the Columbia. (United States Geological Survey) The Columbia is considered to be one of the most heavily engineered waterways in the world with over 250 reservoirs and about 150 hydroelectric projects. (United States Army Corps of Engineers) The mad-cap dam construction began in the 1930’s, and by the middle of that decade the four largest concrete damns ever built were under construction. The next forty-odd years saw literally hundreds of pork-barrel federal water projects undertaken in the Columbia Basin. By the mid-1970’s the Columbia was fully modified for freight. Currently there are 13 dams on the mainstream, and over a hundred others on its tributaries. (Harden) In 1961, the US and Canada signed a treaty relating to cooperative development in the basin. This treaty is falls within the scope of the International Joint Commission (IJC) established in 1909. It should be noted that the 1961 treaty includes no direct mention of water quality issues. Under the treaty a permanent engineering board is to be established to report on the progress of the development. One of their duties is: “(e) make reports to the United States of America and Canada at least once a year of the results being achieved under the Treaty and make special reports concerning any matter which it considers should be brought to their attention;” This is as far as water quality was addressed in the treaty. (United States) The Problem: The Columbia River Basin has within the last century seen a drastic decline in the anadromous fish population within the region. While a myriad of factors can be attributed to this trend, economic development with the basin can be best linked to the water quality degradation. The Columbia River Basin streams, both main and tributaries, have been designated as “water quality impaired” under the Clean Water Act (CWA). (Federal Caucus, 1999) Historically, 10 to 16 million salmon and steelhead returned annually to spawn within the basin, but by the 1960’s that number was reduced to 5 million. (Federal Caucus, 1999) The population was further reduced to about a million by the late ‘90’s, with most of this number produced in hatchery operations. (Wright) Due to this steep reduction in population the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) has listed 12 stocks of salmon and steelhead as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). In addition, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) listed bull trout, Kootenai River White Sturgeon, and 5 other aquatic species as threatened or endangered. (Federal Caucus, 1999) Under the EAS the NMPS is responsible for developing a plan to restore anadromous species populations. (United States Fish and Wildlife) The restoration effort has been ongoing sine the late 1990’s. The scope of the problem is large, the factors numerous, and the issues complex. The level of institutional cooperation is already extremely high. A multitude of organizations; federal, state, and local, have come together to formulate a comprehensive means for restoration. The various alternative solutions that have been developed vary on any number of issues due to the stake that the various actors, and the groups they have formed, have within the basin. These solutions run the gambit from “do nothing,” to complete natural river restoration. Questions: 1) 2) How do Tribal Nations (First Peoples) affect any US-Canada treaty in the basin? How broad will the affect of the breach of treaties with Tribal Nations (First Peoples), and/or the method in which the US and Canada address their concerns be on development of other trans-boundary treaties or agreements? If mismanaged, will the US or Canada be looked at negatively when attempting to help other nations water development? Required Readings: Skim Columbia River Basin-Dams and Salmon Federal Caucus (Skim the two links at the bottom for a bit more.) Umatilla Indian Reservation Salmon Policy (It’s a bit lengthy, read I, II, and skim the rest) Works Cited (and More Readings): Federal Caucus Comment Record. (Winter 2000, Issues 3) Citizen Update, Conservation of the Columbia Basin Fish, Public Meetings Planned & Report Summaries. Federal Caucus, The. (December 1999) Conservation of Columbia Basin Fish, Building a Conceptual Recovery Plan. Harden, Blaine. A River Lost. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. New York, NY. 1996. pages 17, 25. Northwest Power Planning Council. (February, 2000) The Year of Decision, Renewing the Northwest Power Planning Council’s Fish and Wildlife Program. United States and Canada. Treaty relating to cooperative development of the water resources of the Columbia River Basin (with Annexes) (Available online October, 2005 http://www.internationalwaterlaw.org/RegionalDocs/Columbia_River1961.htm) United States Army Corps of Engineers. Columbia River Basin-Dams and Salmon. (Available online October, 2005 http://www.nwd.usace.army.mil/ps/colrvbsn.htm). United States Fish and Wildlife. The Endangered Species Act of 1973. (Available online October, 2005 http://endangered.fws.gov/esa.html). United States Geological Survey. CVO Website-Columbia River Basin. (Available Online October, 2005 http://vulcan.wr.usgs.gov/Volcanoes/Washington/ColumbiaRiver/description_columbia_river .html). Wright, Steven J., Ahamd-Ali Honarpisheh. (2000) Temperature and Dissolved Gas Modeling Applied to Salmon Restoration Efforts. Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, The University of Michigan.