Columbia river basin

advertisement

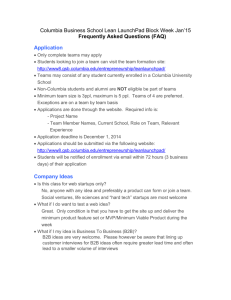

Laura Sampson Transboundary Waters Presentation date: 2/16/2012 Columbia River Basin: Transboundary Issues in the Pacific Northwest Background: The Columbia River is the fourth largest river in the United States and is one of the few major rivers shared with other countries. The 1,243 mile long river originates at Columbia Lake in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, Canada, and then flows through Washington before emptying into the Pacific Ocean at Astoria, Oregon. It’s watershed is about as big as France and touches seven U.S. states (WA, OR, ID, MT, WY,UT, NV) and a Canadian province (BC). While the river starts in Canada, almost 85% of the basin’s area and 75% of the runoff is contributed by the United States. The largest tributary is the Snake River, which starts in Yellowstone Wyoming. The average annual discharge is 78,510,000 acre-ft putting more water than any other N. American river into the Pacific Ocean. Both the culture and the economy of the Pacific Northwest have been heavily dependent on the Columbia River and its tributaries for thousands of years. The many tribes in the region have been using them for transportation, food and trading since ancient times. The economies of modern cities like Portland are also based on the river system. The basin is home to many fish that migrate between freshwater habitats and the Pacific Ocean and do not spawn elsewhere in the nation. The Columbia has an elevation drop of 2,650 ft which is twice that of the Mississippi River in half of the distance. This relatively steep grade combined with the heavy flow makes the Columbia River basin a great place to produce and use hydroelectric power. There are 14 hydroelectric dams on the Columbia's main stem and many more on its tributaries that together produce more hydroelectric power than those of any other North American river. According to the Army Corps of Engineers, the Columbia has 250 reservoirs making it one of the most heavily engineered waterways in the world. Interaction with Canada: Many approaches to international water management have been utilized in the Columbia River system for almost eight decades. Because Canada and the US are both upstream and downstream negotiations have been relatively tranquil. The Kootenay River(shown to the Right) is a good example of this. In general, the agreements have focused on equality rather than equity despite the disproportionate populations and economies of the two nations. The Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909 was the first time this attempt at legislation. The treaty covers the “ Main shore to main shore of the lakes and rivers and connecting waterways, or the portions thereof, along which the international boundary between the United States and the Dominion of Canada passes, including all bays, arms, and inlets thereof, but not including tributary waters which in their natural channels would flow into such lakes, rivers, and waterways, or waters flowing from such lakes, rivers, and waterways, or the waters of rivers flowing across the boundary.” It established the International Joint Commission(IJC) which was charged with making sure that international waters like the Columbia remained “free and open”. While the IJC was successful at settling disagreements over transboundary transportation, disagreements over the the installment of dams and the principle of sharing downstream benefits heated up along with concerns over flooding in the 1940’s and 1950’s. By 1964 the federal governments had negotiated and signed the Columbia River Treaty (CRT) to reduce flooding and address the growing demand for energy. The CRT required Canada to provide 15.5 million acre-ft of storage by building three dams and states that the US and Canada will equally share the downstream benefits for hydropower and flood control in the US that result from the three dams development. The United paid Canada 64.4 million dollars as payment for flood protection through 2024, which was estimated to be half of what the flood damages would have been without the treaty. They also paid 254 million dollars for the first 30 years of Canada’s share of power produced downstream, a sum sufficient to pay for the construction of the CRT dams. The CRT also allowed the US to build Libby Dam. In September of 2024 the pre-determined flood control obligations in the treaty will expire. The treaty requires ten years of advanced notice for changes making September of 2014 the First time either country can request alterations to the agreement. As soon as two years from now, either country might want to terminate the treaty, negotiate new flood control obligations and benefits or simply extend the existing terms and conditions. Both governments are currently reviewing the treaty. Although the CRT's hydropower and flood control objectives have been met for several decades, the nations might want to address the increased value society places on endangered biota, environmental quality, and sustainability. Native American issues: The United States and Canada have had very different relations with the original Columbia River Basin Natives. Both pursued treaties with Indians to establish rights to land and resources; while negotiations in the US started as early as the 1700’s, formal agreements in Canada did not appear until 1960. The United States officially recognized the sovereignty of Indian peoples in 1832 when the United States Supreme Court ruled in Worster v. Georgia that the “several Indian nations” had legal status as “political communities within which their authority is exclusive.” On their reservations, created by treaties with the United States, Indians had exclusive authority, and this authority and all rights to land within the reservations were “not only acknowledged but guaranteed by the United States,” according to the court. This lasted for about a decade before manifest destiny fueled westward expansion. When settlers began to pour into the Columbia River Basin in the 1840s, conflicts with Indian tribes led to hostilities. Despite the specific direction of Worster v. Georgia, the United States government sought to push Indians off their lands and onto reservations. Isaac Ingalls Stevens was sent to handle the treaties with the natives and signed the treaty of Walla Walla to lessen the resistance to the reservations. The treaty which has been referenced in several lawsuits between tribes and the US in recent history states, “The exclusive right of taking fish in all the streams where running through or bordering said reservations, is further secured to said confederated tribes and bands of Indians, as also the right of taking fish at all usual and accustomed places, in common with citizens of the Territory.” While there have been some water rights conflicts regarding the boundaries of reservations, the current concerns of native populations are the availability and health of anadromous fish. Historically 15 million Salmon returned to the basin to spawn every year, however this number has decreased dramatically as both nations began to build dams. The Dams physically blocks the path of the fish, increase the temperature as well as the nitrogen levels. In modern times, less than 2 million salmon return each year and most are from hatcheries. Many of the historic species have become endangered or threatened and the tribal nations feel that their fishing rights are being ignored. The government, power companies and dam owners have attempted to alleviate the problem by building fish ladders, juvenile bypass systems, and other creative fish moving techniques in addition to downstream hatcheries. Studies are also being done on the potential impact of removing some of the less efficient dams. One consequence of fish ladders and bypass systems is that sea lions have figured out where the salmon leave the structures. Oregon and Washington approved a highly controversial lethal injection program to manage the sea lion population in 2007. The tribes of the Columbia River Basin have also become concerned about the bioaccumulation of mercury and other toxins found in the Salmon. In 1996 the Model Toxics Control Act established cleanup levels for surface waters assuming a fish consumption rate of 54.1 grams/day. Tribes in the area who consume 389 grams/day on average began to campaign for their needs to be reflected by legislation in 2008. By 2010 the Oregon Water Quality standard was raised to 175 grams/d and 583 grams/day was used as the consumption rate for the Rayonier cleanup. Questions: 1) 2) 3) How do you think the US and Canada will handle the expiration of the C.R. treaty in 2024? Should environmental issues be considered in the revised Columbia River treaty? How well do you feel that Native American water issues have been managed in the Columbia River Basin? How do you think their needs should be addressed in the future? Sources: http://waterwiki.net/index.php/International_Managment_in_the_Columbia_River_System http://www.nwcouncil.org/history/Hydropower.asp http://www.epa.gov/osp/tribes/NatForum10/ntsf10_4t_Dunn2.pdf http://www.nwcouncil.org/history/IndianFishing.asp http://www.nwcouncil.org/history/fishpassage.asp http://www.nwcouncil.org/history/IndianTreaties.asp http://www.oregonlive.com/environment/index.ssf/2010/05/at_bonneville_dam_the_sea_lion.html http://www.ccrh.org/comm/river/index.php http://www.ccrh.org/comm/river/legal.htm http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbia_River http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbia_Lake