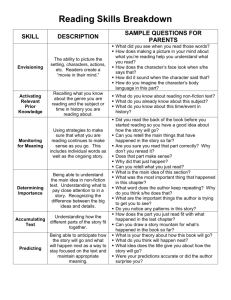

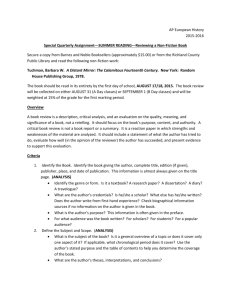

Critical Evaluation of Literary Non-Fiction

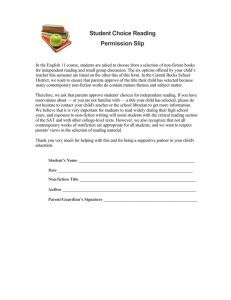

advertisement