Abstract

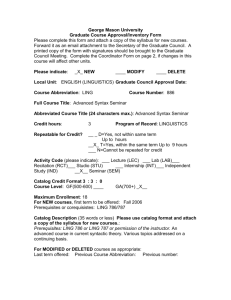

advertisement

Abstracts Dr. Ricardo Bermúdez-Otero Linguistics and English Language, University of Manchester French adjectival liaison: evidence for underlying representations The abuse of opaque derivations and diacritic features in The sound pattern of English (Chomsky & Halle 1968) has led many phonologists and morphologists to regard underlying representations with deep suspicion. Non-standard patterns of adjectival liaison in French, however, suggest that underlying representations have an indispensable role to perform in a suitably constrained theory of morphophonology. Steriade (1999) observes that a non-normative masculine liaison form like [pʁəmjeʁ] in mon premi[eʁ] ami 'my first friend' combines phonological features that surface separately in the citation forms premier [pʁəmje] (m) and première [pʁəmjɛʁ] (f). Crucially, this type of split-base formation never arises in adjectives whose masculine and feminine forms are synchronically suppletive: thus, the liaison form of nouveau [nuvo] 'new' is exactly homophonous with the feminine (i.e. nouvel = nouvelle [nuvɛl], cf. *[nuvol]). Appropriately constrained theories of morphophonology incorporating underlying representations explain this fact: the liaison realization of an adjective can blend properties of alternating masculine and feminine citation forms only if generated from an underlying representation reflecting features of both alternants; this, in turn, is possible only if the grammar contains productive phonological rules capable of deriving the alternation from a single shared underlier. In the paradigm of premier, the relevant phonological processes are the loi de position, which controls the alternation between [e] and [ɛ], and stray erasure, which deletes the latent /ʁ/ if it remains floating at the phrase level. In cases of gender suppletion like nouveau~nouvelle, in contrast, the masculine and feminine citation forms fail to share a single underlier, and split-base liaison realizations are consequently predicted to be impossible. Theories that trade off underlying representations for optimality-theoretic constraints monitoring an expanded network of correspondence relationships among surface forms (Burzio 1996, Steriade 1999) miss this insight: they incorrectly predict the existence of grammars that automatically generate new split-base allomorphs like *[nuvol] by blending submorphemic properties from different cells in suppletive paradigms. Burzio, Luigi. 1996. Surface constraints versus underlying representation. In Jacques Durand & Bernard Laks (eds.), Current trends in phonology: models and methods, vol. 1, 123-41. Salford: European Studies Research Institute, University of Salford. Chomsky, Noam & Morris Halle. 1968. The sound pattern of English. New York: Harper & Row. Steriade, Donca. 1999. Lexical conservatism in French adjectival liaison. In J.-Marc Authier, Barbara E. Bullock & Lisa Reid (eds.), Formal perspectives on Romance linguistics, 243-70. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Professor Maggie Tallerman School of English Literature, Language & Linguistics, Newcastle University No syntax rubicon in language evolution It has become axiomatic within Minimalist circles that the genetically-determined aspects of the language faculty are extremely limited, most likely consisting of a single syntactic principle, Merge (e.g. Chomsky 2005). Features once considered to be part of Universal Grammar, therefore under genetic control, are now assumed to be due to ‘third factor’ effects (Chomsky 2005, 2010) – the result of natural or physical laws of form, rather than traits that are part of the language faculty itself, and which thus need to be accounted for in terms of natural selection. Minimalist theorizing also proposes that language is a very recent phenomenon, a rubicon that was only crossed around 150 thousand years after the speciation of Homo sapiens, which itself occurred c. 195 kya (thousand years ago). For example, Berwick & Chomsky (2011: 27) suggest that ‘the generative procedure [i.e. Merge, MT] [...] emerged some time in the 50,000 – 100,000 year range [...] presumably involving some slight rewiring of the brain’. Moreover, the language faculty owes its origins to an internal ‘language of thought’, which only subsequently became externalized and thus used for communicative purposes. Along with these claims, Minimalist theorists strongly deny the existence of a pre-syntactic (or semi-syntactic) protolanguage stage in the evolution of the language faculty: ‘there is no room in this picture for any precursors to language – say a language-like system with only short sentences’ (Berwick & Chomsky 2011: 31). The reason for this is that Merge is an all- or-nothing concept: Berwick (2011: 99) claims that ‘there is no possibility of an intermediate language between a non-combinatorial syntax and full natural language syntax – one either has Merge in all its generative glory, or one has effectively no combinatorial syntax at all’. Here, I challenge both the idea that there was a recent syntax saltation – a vast rubicon to be crossed catastrophically – and the idea that the language faculty initially arose to support thought. I also defend a gradualist approach to the evolution of syntax, more in keeping with general neo-Darwinian principles. Under this scenario, forms of protolanguage used for communication became increasingly more sophisticated syntactically, and though Merge is a crucial development, it was merely one of many steps along the way to fully-fledged syntax – and probably not even the final step. Dr. Erich Round School of Languages & Comparative Cultural Studies, University of Queensland Big data typology, linguistic phylogenetics, and why data design will be crucial Biostatistical methods have dramatically increased our ability to infer the genetic history of earth's species, and since languages also possess a genealogical past, there is a strong impetus to extend these methods from genetic to linguistic data. However, automated statistical analysis places new demands on linguistic input data. Explaining precisely what those demands are, and how we can best respond to them, will be the task of a new theory of linguistic data design. In this talk I examine two challenges which will be foundational concerns for this new theory. 1. Variables’ incommensurability Central to new statistical techniques is the comparison of large numbers of variables, each assigned a value for some set of languages to be investigated. An indispensable assumption made by statistical techniques is that variables are valued commensurately from one language to the next. In linguistics, many variables which suggest themselves as good candidates for analysis, for example <Does the language possess prenasalised stops?> are high-level ‘macro variables’, whose values follow from the values of a multitude of rather narrow ‘micro variables’ such as <Does [NC] appear word initially?> or <Does /NC/ contrast with /N+C/?>. However, when we examine linguistic practice, we find that the analysis of two languages may well assign an identical (or different) value to the macro variable, even though the languages share none (or all) of their values of the constituent micro variables. Thus macro variables may often be incommensurate across languages. A shift of focus onto micro variables, which becomes increasingly practical in a ‘big data’ environment, may offer solutions. 2. Data biases from sources other thanhistory The statistical inference of languages’ histories is made feasible by the combination of two facts: (i) historical lineages and interactions among languages leave traces in present day observations; and (ii) those traces possess certain mathematical properties (such as correlation) which are distinguishable from noise, given appropriate models and enough data. Muddying the waters, however, is the fact that identical mathematical properties (such as correlation) can be introduced by nonhistorical sources, such as biases introduced in data collection, interpretation, encoding, and so forth. Since these biases will be confusable systematically with real historical signals, we will be well served by a good understanding of their sources, nature and magnitude; and also the effects they may have on statistical results if they are present. To address the latter concern, I describe a series of experiments which manipulates the prevalence of four kinds of mathematical properties in a large typological dataset, and examine the effects it has on the performance of a Bayesian clustering algorithm, Sturcture (Pritchard et al. 2000). The results are rather striking, and demonstrate the need for a new kind of understanding of linguistic datasets, one which our discipline has not explicitly needed previously, but whose time has come. Professor Mary Dalrymple The go-to construction The "go-to" construction is composed of a form of the verb "go" followed by an infinitive: "she went to sit up [but fell back onto the bed]", "he went to catch the ball [but missed it]". It conveys that the action of the complement verb was not completed, or was completed in an unexpected manner. To our knowledge, this construction has not previously been noticed or described in the literature. We provide a theoretically informed account of its syntactic, semantic and pragmatic properties in a wider typological context. Dr. Nina Kazanina School of Experimental Psychology, University of Bristol Beyond the input: abstract categories in language I will discuss phenomena in psychology of language that necessitate abstracting away from input and require creation of categories that project beyond what is objectively present in the input. First, I’ll discuss abstraction/categorization in the domain of speech perception and will use MEG and EEG findings to argue that this process affects very early stages of sound processing. Second, I’ll discuss abstraction/categorisation in the domain of counterfactual past events. Adult speakers have little difficulty grouping various instances of an incomplete event (e.g., dissimilar incomplete events of house-building) under the same linguistic label (e.g., ‘… was building a house’), and I will investigate how this ability develops in 3-6 year old children. In general, I will argue that abstraction and categorisation are indispensable and non-reducible strata in language. Dr. Linnaea Stockall School of Languages, Linguistics & Film, Queen Mary University of London I saw, I unsaw, I resaw: how we access and make use of unconscious knowledge about verbal roots In this talk I'll discuss a number of experiments investigating how we rapidly and accurately access information about the verbal roots of morphologically complex words like 'saw' or 'jumped', and morphologically complex pseudo words like 'unthink' and 'redance'. The experiments range from simple button press experiments in which participants say whether they think strings like 'ungrow' are a possible word of English or not, through eye-movement studies in which words like 'unthinkable' occur in natural sentence context, to studies using MEG to investigate the millisecond by millisecond neural activation patterns involved in processing complex words. I'll show that by focusing on the apparently simple question of how we detect and make use of information about verbal roots, we can gain significant insight into the overall architecture of the human linguistic system. Professor Andreas Willi Of angry men and almighty gods — or how to tell a story in Indo-European Professor Giuseppe Longobardi Department of Language and Linguistic Science, University of York Language, history, and the cognitive revolution Beyond its theoretical success, the development of molecular biology has brought about the possibility of extraordinary progress in the historical study of classification and distribution of different species and different human populations, introducing a new level of evidence (molecular genetic markers) now susceptible to quantitative and computational treatment. I argue that, even in the cognitive sciences, purely theoretical progress in a certain discipline, such as linguistics, may have analogous historical impact, equally contributing to Renfrew’s ‘New Synthesis’, and in turn may be confirmed by such results. So, exactly on the model of molecular biology and its fruitful balance between evolutionary and theoretical concerns, I propose to unify two traditionally unrelated lines of investigation: 1) the formal study of syntactic variation (parameter theory) in the biolinguistic program 2) the reconstruction of relatedness among languages (phylogenetic taxonomy) I argue that due to progress in parametric grammatical theories, and relying on the methodological parallelism with evolutionary genetics, we are now in a position to measure the syntactic distance among languages in a precise fashion and to explore its historical significance through the application of clustering algorithms borrowed from computational biology. Through such formal methods, it can be shown that the distribution of actual syntactic distances provided by an elaborate parametric system is statistically highly significant (that is, non-accidental and requiring historical explanation). The empirical analysis of the languages involved in the experiment has been conducted with the particular strategy of focusing on a single module of grammar, namely nominal phrases at this stage. The properties commonly attributed to parametric variation (uniform discreteness and universality), akin to those displayed by genetic polymorphisms, make it particularly suitable for addressing the unsolved issue of comparison between remote, etymologically unrelated languages, opening the way for completely new interactions with the empirical results of molecular anthropologists. Corroborating these results with further experimentation, I will conclude that the rate of evolution of syntax in the history of a language is lower than that of lexical replacement (syntax is more inertial diachronically). Thus, I want to suggest 3) that a parametric model of the language faculty and language acquisition/transmission (more broadly of generative grammar) receives original support from its historical adequacy. 4) that through these new tools one can explore the possibility of testing Darwin’s prediction that, when properly identified, the trees of human populations and of their languages should eventually turn out strictly parallel. 5) that the so-called ‘Galilaean style’ of inquiry (based on descriptive accuracy, idealization, deductive structure of theories...), sometimes invoked as a model for the rising cognitive sciences as well as the classical natural ones, may be profitably transposed from theoretical and synchronic study to that of human (language) history.