- NCCPeds

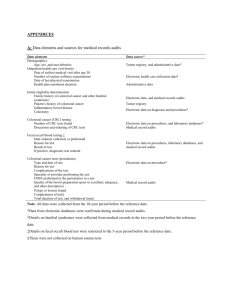

advertisement