Many clinical and epidemiologic studies have shown a high

advertisement

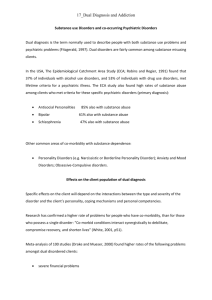

1 Neurotoxicity Research (accepted 05.01.06) IMPORTANCE OF CLINICAL DIAGNOSES FOR COMORBIDITY STUDIES IN SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS Marta Torrens, M.D, Ph.D. and Rocío Martin-Santos, M.D, Ph.D. Drug Abuse Unit, Institut d’Atenció Psiquiàtrica (IAPS), Hospital del Mar, Universitat Autònoma Barcelona, Passeig Marítim 25−29, E-08003-Barcelona, Spain (e-mail: mtorrens@imas.imim.es) 2 ABSTRACT Many clinical and epidemiologic studies have shown a high frequency of cooccurrence of substance abuse and psychiatric disorders, with important consequences from health and social perspective. However, the identification of reliable and valid diagnosis of psychiatric co morbidity in substance abusers is problematic, mainly because the acute or chronic effects of substance abuse can mimic symptoms of many other mental disorders, making difficult to differentiate psychiatric symptoms that represent effects of acute or chronic substance use or withdrawal, of those that represent an independent disorder. While DSM-IIII-R and earlier nomenclatures were unclear in differentiating independent from other psychiatric disorders, DSM-IV and DSM-IV-TR provided clearer guidelines in diagnosing psychiatric disorders in heavy users of alcohol and drugs, providing three categories: “primary” psychiatric disorders, “substance-induced” disorders, and “expected effects” of the substances, meaning expected intoxication and/or withdrawal symptoms that should not be diagnosed as symptoms of a psychiatric disorder. The use of the “Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders (PRISM)”, a structured interview developed to improve the diagnosis of co morbidity in drug abusers according DSM-IV, supplies new opportunities in the clinical research in this field. Key words: dual diagnosis, psychiatric comorbidity, structured interview, PRISM 3 INTRODUCTION The high frequency of co-occurrence of substance abuse and other psychiatric disorders documented in different clinical and epidemiologic studies is a matter of great concern because of its relevant diagnostic and therapeutic implications. This co-occurrence, also known as ‘psychiatric comorbidity in drug abusers’ or ‘dual diagnosis’ has been associated with poor outcome of subjects affected. In comparison with patients with a single disorder, dually-diagnosed patients show a higher psychopathological severity, more emergency admissions (Curran et al., 2003; Martín-Santos et al., 2006), significantly increased rates of psychiatric hospitalization (Lambert et al., 2003), and a higher prevalence of suicide (Oyefeso et al., 1999; Appleby, 2000; Aharonovich et al., 2002). In addition, comorbid drug abusers show an increased rate of risk behaviors and related infections, such as HIV and hepatitis C and B virus infection (King et al., 2000; Carey et al., 2001; Rosenberg et al., 2001) as well as psychosocial impairments, such as higher unemployment and homelessness rates (Caton et al., 1994; Vazquez et al., 1997), and a great amount of violent or criminal behavior (Abram and Teplin, 1991; Cuffel et al., 1994;). Although convincing evidence supports a strong association between a variety of psychiatric disorders and substance use disorders, the nature of this relationship is complex and may vary depending on each particular disorder. The neurobiological mechanisms and substrates involved in the co-occurrence of addiction and other psychiatric disorder are currently a priority area of research. Two main hypothesis explains comorbidity: 1) addiction and other psychiatric disorders are different symptomatic expressions of similar preexisting neurobiological abnormalities, and 2) repeated drug administration, through 4 neuroadaptation, leads to biological changes that have common elements with abnormalities mediating certain psychiatric disorders. Recently, the neurobiological effects of chronic stress as the bridging construct between psychiatric and substance use disorders constitutes a promising area of research (Brady and Sinha, 2005). In spite of the relevance of providing effective treatment for dual diagnosis, previous studies have reported many difficulties and poor outcome when treating patients with co-occurrence of substance abuse and other psychiatric disorders. In fact, current data from randomized controlled studies, in the treatment of major depression in substance abuser patients (one of the most frequent of co-occurring disorders in this population) show a poor efficacy of antidepressant drugs (Nunes and Levin 2004; Torrens et al., 2005). Accordingly, the study of factors related to the neurobiological mechanisms involved in the dual diagnosis and the development of effective treatments has major clinical implications (O’Brien et al., 2004). But in the core of such research remains an important issue, that is, the methodological difficulties in diagnosing comorbid psychiatric disorders in a substance abuser population, suggesting the crucial role of diagnostic accuracy in the selection of participants both for neurobiological studies and for controlled clinical trials aimed to assess the efficacy of different therapeutic interventions. The identification of valid and reliable instruments to establish a definite diagnosis of comorbid psychiatric disorders in substance abusers has long been regarded as problematic. In this report, we summarize the methodologic problems and evolution of diagnostic concepts in psychiatric comorbidity in substance abuse. The characteristics of the different diagnostic instruments 5 available, particularly the Psychiatric Research lnterview for Substance and Mental Disorders for DSM-IV (PRISM-IV) (Hasin et al., 2001) are also commented on. IDENTIFICATION OF PSYCHIATRIC COMORBIDITY IN SUBSTANCE ABUSERS: DIAGNOSTIC CONCEPTS AND INSTRUMENTS The clinical identification of psychiatric comorbidity in substance abusers constitutes a challenge for both medical care and research in dual diagnosis. A major problem is to establish an accurate diagnosis that has two main difficulties. Firstly, acute or chronic effects of substance abuse can mimic symptoms of many other mental disorders making it difficult to differentiate psychiatric symptoms that represent an independent (primary) disorder from symptoms of acute or chronic substance use or withdrawal. Secondly, psychiatric diagnoses are syndromes rather than diseases with known pathophysiology and associated biological markers. This lack of biological markers has forced psychiatrists to develop operative diagnostic criteria, including the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM] and the International Classification of Diseases Diagnostic Criteria [ICD], and to design structured clinical diagnostic interviews to improve the validity and reliability of diagnoses. The use of standard criteria based on directly observable behavioral symptoms and the incorporation of these into structured interviews, maximizes the extent to which the same information is elicited and applied to the same criteria to achieve diagnosis. In this section, a summary of the evolution of the diagnostic concepts on comorbidity and the characteristics of the currently available structured diagnostic instruments is presented. 6 Evolution of the diagnostic concepts on comorbidity Historically, most diagnostic criteria used for diagnosing psychiatric disorders offered little specific guidance for determining the presence of other cooccurring psychiatric diagnosis from the clinical records of patients affected by substance use disorders. The approaches to diagnosis of co-morbid psychiatric disorders among substance abuser patients evolved from the simple one in Feighner criteria which distinguished between “primary” and “secondary” disorders according to age at onset of each disorder, being the disorder diagnosed at the earliest age that named “primary” (Feighner et al., 1972). This distinction is not useful to differentiate whether the second disorder is independent from the first or to assess the relationship between both conditions. Psychiatric disorders tend to have characteristic ages of onset, for example, conduct disorders begin in childhood, substance use disorders in early to mild adolescence, and mood disorders in adolescence and adulthood. Therefore, according to the natural history, antisocial personality disorder would be considered “primary disorder” and mood disorder “secondary disorder”. Later, Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) (Spitzer et al., 1978), DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association [APA, 1980) and DSM-III-R (APA, 1987) used the concept of "organic" vs. “nonorganic” disorders, more theoretically based, but poorly defined and put into operation. In these classification systems, subjects in whom organic factors may play a significant role in the development of the psychiatric disturbance were not considered as having an independent psychiatric disorder. However, specific criteria for distinguishing organic from non-organic disorders were not provided, leaving the differentiation 7 process unclear. Because alcohol and drug abuse has shown an increase among patients with psychiatric disorders, this lack of specificity became increasingly problematic. DSM-III and DSM-III-R similarly defined “organic” etiology. A psychiatric syndrome was considered as nonorganic if it could not be established that an organic factor initiated and maintained the disturbance. As in RDC, specific criteria for this decision were not provided, leaving room for discrepant approaches. Then it is not surprising that the studies using RDC, DSM-III and DSM-IIIR criteria even using structured diagnostic instruments, such as the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version (SADS) (Endicott and Spitzer, 1978) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (Spitzer et al., 1992), showed poor reliability (Rounsaville et al., 1991; Bryant et al., 1992; Williams et al., 1992; Ross et al., 1995) and validity (Kadden et al., 1995; Kranzler et al., 1996; 1997) for psychiatric diagnoses in substance abusers. In addition, a poor agreement seen among groups even when using the same measures was observed (Weiss et al., 1992). In response to the increasing recognition of the relevance of comorbid psychiatric disorders in drug users, both DSM-IV (APA, 1994) and ICD-10 (World Health Organization, 1993) emphasized more the clarification of the diagnoses of psychiatric disorders in heavy users of alcohol and drugs. DSM-IV, DSM-IV-TR The DSM-IV (APA, 1994) placed more emphasis on comorbidity, replacing the dichotomous terms “organic” vs. “nonorganic” to distinguish three categories: “primary” psychiatric disorders, “substance-induced” disorders and “expected 8 effects” of the substances, meaning expected intoxication and/or withdrawal symptoms that should not be diagnosed as symptoms of a psychiatric disorder. DSM-IV-Text Revision (APA, 2000) provides more specific guidelines for establishing this differentiation. A “primary” disorder is diagnosed if symptoms are not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance. To classify a disorder as “substanceinduced”, a primary classification must be first ruled out. There are four conditions under which an episode that co-occurs with substance intoxication or withdrawal can be considered primary: 1) when symptoms are substantially in excess of what would be expected given the type or the amount of the substance used or the duration of use; 2) a history of non-substance-related episodes; 3) the onset of symptoms precedes the onset of the substance use; and 4) the symptoms persist for a substantial period of time (i.e., at least a month) after the cessation of intoxication or acute withdrawal. If neither “primary” nor “substance-induced” criteria are met, then the syndrome is considered to represent intoxication or withdrawal effects of alcohol or drugs. A “substance-induced” disorder is diagnosed when DSM-IV symptom criteria for the disorder are fulfilled; the episode occurs entirely during a period of heavy substance use or within the first 4 weeks after cessation of use; the substance used is “relevant” to the disorder (i.e., its effects can cause symptoms mimicking the disorder being assessed); and the symptoms are greater than the expected effects of intoxication and/or withdrawal. The “expected effects” are the predicted physiological effects of substance abuse and dependence. They are reflected in the substance specific symptoms of intoxication and withdrawal syndromes for each main category of 9 substances. The expected effects can appear to be identical to the symptoms of primary mental disorders (e.g., insomnia, hallucinations). ICD-10 The ICD-10 provides specific criteria to differentiate between primary disorders and disorders resulting from psychoactive substance use, but only for psychotic disorders. As in DSM-IV, ICD-10 excludes psychotic episodes attributed to psychoactive substance use from a primary classification. In ICD-10, psychosis can be attributed to psychoactive substance use under three conditions: 1) the onset of symptoms must occur during or within 2 weeks of substance use; 2) the psychotic symptoms must persist for more than 48 h; and 3) the duration of the disorder must not exceed 6 months. A psychotic disorder attributed to psychoactive use can be specified as predominantly depressive or predominantly manic. However, unlike DSM-IV, ICD-10 does not provide a separate psychoactive substance- related category for any other type of psychiatric disorder. By definition, ICD-10 “organic mental disorder” excludes alcohol or other psychoactive substance-related disorders. ICD-10 organic mood disorder and organic delusional disorder cannot be used to diagnose episodes co-occurring with heavy psychoactive substance use. Furthermore, the DSM-IV concept of symptoms that are greater than the expected effects of intoxication and withdrawal is not included in ICD-10. Structured diagnostic instruments Different interviews for psychiatric diagnosis based on DSM-IV or ICD-10 criteria are available for clinical and research studies, including the Structured 10 Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) (First et al., 1997), The Schedule for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN) (Janca et al., 1994), The Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (WHO, 1998), and the Psychiatric Research lnterview for Substance and Mental Disorders for DSM-IV (PRISM-IV) (Hasin et al., 2001). Other instruments designed for epidemiological surveys like “Alcohol Use Disorders and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV version” (AUDADIS) (Grant et al., 2001) are not included in this review. SCID-IV The SCID-IV is a semi-structured interview that allows diagnosis of primary or substance-induced disorders but provides no more specific guidelines than stated in the criteria. The differentiation of “primary” and “substance induced” disorder is made on a syndrome level in the SCID. The interviewer assesses the substance etiology in a two step process, as shown for example in the section on depression. In the SCID Depression module, DSM criteria and a list of “etiological substances” are provided. The subject is asked if she/he has been drinking or using street drugs before the episode. Based on the subject’s response, the interviewer decides if there is a possibility of ruling out a diagnosis of primary depression. If so, the interviewer skips to a series of questions about the temporal relationship of the mood symptoms and substance use and if the mood symptoms were greater than the expected effects of the substance used. Because the SCID relies on the interviewer’s clinical judgment, the SCID assessment of substance etiology can be problematic. First, the question about the relevant extent of the subject’s 11 substance use will often yield information that is open to interpretation. Second, the “primary” vs. “substance-induced” differentiation is established on the level of syndromes and specific guidelines for differentiating from the expected effects of intoxication or withdrawal are not provided. Finally, questions to assess the temporal relationship of the episode and substance use are unstructured, potentially causing unclear or inaccurate information. At the present time, reliability data for the SCID-IV in substance abusing samples are not available. The data of validity will be reported later in this review. SCAN The SCAN is a set of instruments for assessing a range of clinical phenomena. A core instrument of the SCAN is the Present State Examination (PSE-10). The PSE covers “present state”, the month before the examination, and “lifetime before”. PSE ratings are coded on score sheets and based on these ratings, a computer program generates ICD-10 and DSM-IV diagnoses. The PSE is a semi-structured clinical examination in which the interviewer uses clinical judgment to ascribe specified definitions to clinical phenomena using the SCAN Glossary. The Glossary is a list of definitions of clinical symptoms and experiences. The interviewer questions the subject in detail, matches responses to a description in the Glossary, and then decides if a symptom is present, and if so, how severe. After the subject’s report of a symptom, the interviewer matches it to a Glossary definition, and codes an attributional rating scale for the item. Alcohol and other psychoactive substances are among the available attribution choices, like “known primary intracranial process”, non-psychiatric medication, and toxins. The decision to assign attribution to a psychoactive 12 substance rests on the clinician’s judgment based on information taken from the interview. The SCAN does not provide specific guidelines for differentiating between substance-related and independent disorders. As far as we are aware, data on the SCAN reliability or validity of psychiatric diagnosis in substance abusers are not available. CIDI The CIDI is a fully structured interview designed for survey interviewers who read the questions as written without interpretation (Robins et al., 1988). For the primary–substance-induced differentiation, the CIDI relies largely on the subject’s opinion. The DSM-IV concept of “expected effects” of intoxication or withdrawal vs. symptoms greater than these effects is not addressed in the CIDI. The CIDI generates ICD-10 and DSM-IV diagnoses. In the CIDI, symptoms attributed to alcohol, drugs, or physical illness are eliminated for consideration when making the psychiatric diagnoses. This symptom-level evaluation represents a departure from earlier procedures. Generally, the presence of substance-related factors is evaluated for the entire period of disorder once it has been established, rather than on a symptom-by-symptom basis before determining if any episode of the disorder has occurred. In a preliminary study, we performed a validation study of the Spanish version of the screening section of the CIDI to detect psychiatric comorbidity according DSM-IV criteria (Astals et al., 2001). A total of 175 opioid dependent subjects were assessed with the screening section of CIDI and, in a blind fashion, by an independent researcher using the PRISM. The results obtained 13 indicate a high sensitivity in most of the psychiatric co-morbid diagnoses, but a low specificity in many of them, as is shown in Table 1, suggesting the need to improve the specificity of the instrument to detect psychiatric disorders in substance abusers. PRISM-IV The PRISM was designed to improve the reliability problems in the diagnosis of comorbid psychiatric disorders in substance-abusing samples. The PRISM was initially developed and tested for DSM-III-R criteria and used many aspects of the SCID as a starting point (Hasin et al., 1996). Three important characteristics of the PRISM that are specific to comorbidity are as follows: 1) adding specific rating guidelines throughout the interview, including frequency and duration requirements for symptoms, explicit exclusion criteria, and decision rules for frequent sources of uncertainty; 2) positioning of the alcohol and drug sections of the PRISM near the beginning of the interview, before the mental disorder sections, so that the history of alcohol and drug use is available at the time of beginning the assessment of mental disorders; and 3) more structured alcohol and drug histories to provide a context for assessing comorbid psychiatric disorders. The first version of PRISM, based on DSM-III-R criteria, showed good to excellent reliability for many diagnoses, including affective disorders, substance use disorders, eating disorders, some anxiety disorders, and psychotic symptoms (Hasin et al., 1996). To address the changes in DSM-IV, the PRISM was updated and revised to provide diagnoses of primary and substance-induced disorders and to include the expected effects of intoxication or withdrawal. In addition, the revised version of the PRISM provides a method 14 for operationalizing the term “in excess of” the expected effects of substance in chronic substance abusers (Hasin et al., 1998). This interview includes the following disorders: 1) substance use disorders: substance abuse and dependence for alcohol, cannabis, hallucinogens, licit and illicit opiates, and stimulants; 2) primary affective disorders, including major depression, manic episode (and bipolar I disorder), psychotic mood disorder, hypomanic episode (and bipolar II disorder), dysthymia, and cyclothymic disorder; 3) primary anxiety disorders, including panic, simple phobia, social phobia, agoraphobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder; 4) primary psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder, and psychotic disorder not otherwise specified; 5) eating disorders, including anorexia, bulimia, and binge-eating disorder; 6) personality disorders, including antisocial and borderline personality disorders; and 7) substance-induced disorders, including major depression, mania, dysthymia, psychosis, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. A validity study comparing diagnoses obtained through the PRISM-IV and SCID-IV in 105 substance abuser patients from substance/dual diagnosis unit, using the LEAD procedure (Longitudinal, Expert, All Data; Spitzer,1983), as a “gold standard” has been reported (Torrens et al., 2004). In the absence of a biological marker as a “gold standard”, the LEAD procedure is conceived as a standard for validating psychiatric diagnoses (Spitzer, 1983). The LEAD procedure has been employed as a criterion for the assessment of the procedural validity of diagnostic instruments. To develop the LEAD diagnoses, the expert uses all the longitudinal information available for the individual 15 subject, including previous and current clinical evaluations, opinions of other professionals, laboratory results, and data collected from relatives. The reliability and validity of the LEAD procedure for diagnosing some psychiatric comorbidity have been questioned in previous studies (Kranzler et al., 1994; 1997). However, the fact that in these studies the criteria used were DSM-III-R, with the difficulties mentioned above and, in the absence of a better measure, LEAD procedure continues being the best method available. In this study the agreement between the LEAD procedure and the PRISM in current major depression, past substance-induced depression, and borderline personality disorder was better than that obtained between the LEAD procedure and the SCID. Table 2 shows the diagnostic concordance, assessed by kappa statistics, of current non-substance use DSM-IV diagnoses with PRISM-IV, SCID-IV, and LEAD. Recently reliability information in substance abusing samples has been provided for PRISM-IV (Hasin et al., 2006). In a test-retest reliability study of DSM-IV diagnoses obtained by PRISM in 285 substance abusing patients from substance/dual diagnosis and mental health settings, kappas for primary and substance-induced major depression, psychotic disorders, antisocial and borderline personality disorders ranged good to excellent, as is shown in Table 3. reliability for most anxiety disorders was lower. Summarizing, in the last years an effort has been done o improve the identification of co-occurrence of other psychiatric disorders in substance abuser subjects in a reliable and valid manner. Currently, most DSM-IV psychiatric disorders can be assessed in substance-abusing subjects with acceptable to excellent reliability and validity by using specifically the PRISM. 16 CONCLUSIONS The co-occurrence of substance abuse and psychiatric disorders is an important area of research because to the important consequences from a health and social viewpoint, but also it provides an opportunity to study in depth the underlying mechanisms in both substance use disorders and non-substance use disorders, involving genetic mediators and/or neurobiological substrates, and in the development of specific therapeutics strategies. However, rigorous phenotypic assessment is essential for all studies on co-morbidity, because poor or inadequate phenotypic assessment lead to incorrect results. In this respect, the use of a clinical instrument, such as PRISM, which allows diagnosing most of comorbid psychiatric disorders in substance abusers in a reliable and valid manner, offers a useful tool for further comorbidity studies. REFERENCES Abram KM and Teplin LA (1991) Co-occurring disorders among mentally ill jail detainees: implications for public policy. Am Psyhologist. 4, 1036-1045. 17 Aharonovich E, Liu X, Nunes E, and Hasin DS (2002) Suicide attempts in substance abusers: effects of major depression in relation to substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 159,1600-1602. American Psychiatric Association (1980) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd ed. (Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press). American Psychiatric Association (1987) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd ed, rev. (Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press). American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. (Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press). American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed -TR. (Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press). Appleby L (2000) Drug misuse and suicide: A tale of two services. Addiction 95,175-177. Astals M, Domingo-Salvany A, Almendros M, Fos C, Ortells A, Torralba L, and Torrens M (2001) Validación de un instrumento de screening para la 18 detección de patología psiquiátrica en toxicomanías. Trastornos Adictivos 3, 293-294. Brady KT, Sinha R (2005) Co-occurring mental and substance use disorders: the neurobiological effects of chronic stress. Am J Psychiatry. 162, 1483-93. Bryant KJ, Rounsaville BJ, Spitzer RL and Williams JBW (1992) Reliability of dual diagnosis: substance dependence and psychiatric disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 180, 251–257. Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SA, Gordon CM and Vanable PA (2001) Prevalence and correlates of sexual activity and HIV-related risk bahavior among psychiatric outpatients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 69, 846-850. Caton CL, Shrout PE, Eagle PF, Opler LA, Felix A and Dominguez B. (1994) Risk factors for homelessness among schizophrenic men: a case-control study. Am J Public Health. 84: 265-270. Cuffel B, Shumway M and Chouljian T (1994) A longitudinal study of substance use and community violence in schizophrenia. J Nerv Mental Dis, 182, 704708. Curran GM, Sullivan G, Williams K, Han X, Collins K, Keys J and Kotrla KJ (2003) Emergency department use of persons with comorbid psychiatric and substance abuse disorders. Ann Emerg Med. 41, 659-667. 19 Endicott J and Spitzer RL (1978) A diagnostic interview: the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 35, 837–844. Feighner JP, Robins E, Guze SB, Woodruff RA Jr, Winokur G, and Munoz R (1972) Diagnostic criteria for use in psychiatric research. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 26, 57-63. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M and Williams JBW (1997) Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID). (Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press). Grant BF, Dawson DA and Hasin DS (2001) The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV Version. (Bethesda, Md: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism). Hasin DS, Trautman KD, Miele GM, Samet S, Smith M and Endicott (1996) Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders (PRISM): reliability for substance abusers. Am J Psychiatry 153, .1195–1201 Hasin D, Trautman K and Endicott J (1998) Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders: phenomenologically based diagnosis in patients who abuse alcohol or drugs. Psychopharmacol Bull. 34, 3–8 20 Hasin D, Samet S, Meydan J, Miele G and Endicott J (2001) Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders (PRISM-IV). Version 6.0. Hasin DS, Samet S, Nunes E, Meydan J, Matseoane K and Waxman R (2006) Diagnosis of comorbid psychiatric disorders in substance users assessed with the Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders for DSM-IV. Am J Psychiatry. 163: 689-96. Janca A, Ustun TB, and Sartorius N, (1994). New versions of World Health Organization instruments for the assessment of mental disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 90, 73-83. Kadden R, Kranzler H and Rounsaville B (1995) Validity of the distinction between “substance-induced” and “independent” depression and anxiety disorders. Am J Addict. 4, 107–117. Kranzler HR, Kadden RM, Babor TF, Rounsaville BJ (1994) Longitudinal, expert, all data procedure for psychiatric diagnosis in patients with psychoactive substance use disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 182, 277–283 Kranzler HR, Kadden RM, Babor TF, Tenne H, Rounsaville BJ (1996) Validity of the SCID in substance abuse patients. Addiction 91, 859–868. 21 King VL, Kidorf MS, Stoller KB and Brooner RK (2000) Influence of psychiatric comorbidity on HIV risk behaviors: changes during drug abuse treatment. J Addict Dis. 19, 65-83. Kranzler HR, Kadden RM, Babor TF, Tenne H and Rounsaville BJ (1996) Validity of the SCID in substance abuse patients. Addiction 91, 859–868. Kranzler HR, Tennen H, Babor TF, Kadden RM and Rounsaville BJ (1997) Validity of the longitudinal, expert, all data procedure for psychiatric diagnosis in patients with psychoactive substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 45, 93–104 Lambert MT, LePage JM and Schmitt AL (2003) Five-year outcomes following psychiatric consultation to a tertiary care emergency room. Am J Psychiatry. 160, 1350-1353. Martín-Santos R, Fonseca F, Domingo-Salvany A, Ginés JM, Imaz ML, Navinés R, Pascual JC and Torrens M (in press) Dual diagnosis in the psychiatric emergency room in Spain. European J Psychiatry. Nunes EV and Levin FR (2004) Treatment of depression in patients with alcohol or other drug dependence: a meta-analysis. JAMA 291,1887-1896. O'Brien CP, Charney DS, Lewis L, Cornish JW, Post RM, Woody GE, et al (2004) Priority actions to improve the care of persons with co-occurring 22 substance abuse and other mental disorders: a call to action. Biol Psychiatry. 56, 703-713. Oyefeso A, Ghodse H, Clancy C and Corkery J (1999) Suicide among drug addicts in the United Kingdom. Br J Psychiatry. 175, 277-282. Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, Helzer JE, Babor TF, Burke J, Farmer A, Jablenski A, Pickens R, Regier DA, et al. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview. An epidemiologic Instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:1069-77. Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, Swartz MS, Essock SM, Butterfield MI, Constantine NT, Wolford GL and Salyers MP (2001). Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. Am J Public Health. 91, 31-37. Ross H, Swinson R, Doumani S and Larkin E (1995) Diagnosing comorbidity in substance abusers. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 21, 176–185. Rounsaville BJ, Anton SF, Carroll K, Budde D, Prusoff B and Gawin F (1991) Psychiatric diagnoses of treatment-seeking cocaine abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry 48, 43–51. 23 Spitzer RL, Endicott J and Robins E (1978) Research Diagnostic Criteria: rationale and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 35, 773–782. Spitzer RL (1983) Psychiatric diagnosis: are clinicians still necessary? Compr Psychiatry. 24, 399–411. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M and First MB (1992) The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), I: history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 49, 624–629. Torrens M, Serrano D, Astals M, Pérez-Domínguez G. and Martín-Santos R, (2004) Diagnosing Psychiatric Comorbidity in Substance Abusers. Validity of the Spanish Versions of Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders (PRISM-IV) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSMIV (SCID-IV). Am J Psychiatry. 161, 1231-1237. Torrens M, Fonseca F, Mateu G and Farre M (2005) Efficacy of antidepressants in substance use disorders with and without comorbid depression. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 78,1-22. Vazquez C, Munoz M and Sanz J (1997). Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R mental disorders among the homeless in Madrid: a European study using the CIDI. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 95, 523-530. 24 Weiss RD, Mirin SM and Griffin ML (1992) Methodological considerations in the diagnosis of coexisting psychiatric disorders in substance abusers. Br J Addict. 87:179-187. Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB, Spitzer RL, Davies M, Borus J, Howes MJ, Kane J, Pope HG, Rounsaville B and Wittchen H-U (1992) The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), II: multisite test-retest reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 49, 630–636. World Health Organization (1998) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): Core, Version 2.1 (WHO, Geneva). World Health Organization (1992) Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders-Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines, (WHO, Geneva). 25 Table 1.- Sensitivity and specificity of the diagnoses obtained by means of the screenCIDI in respect to diagnoses obtained with the PRISM in a sample of 175 opioid dependent patients. Disorders (DSM-IV) Sensitivity Specificity (%) (%) Affective 100 11 Psychosis 50 74 Panic 100 26 Social Phobia 78 66 Specific Phobia 100 32 26 Table 2.- Diagnostic Concordance of Current DSM-IV Diagnoses with PRISM-IV, SCIDIV, and LEAD (n=105) (Modified of Torrens et al, 2004) Disorder Current diagnoses Concordance (kappa and 95% CI) PRISM-IV vs LEAD SCID-IV vs LEAD Kappa (95% CI) Kappa (95% CI) Affective .68 (0.47-0.89)* .28 (0.07-0.49) .33 (0.07-0.59) .29 (0-0.63) .56 (0.38-0.74)* .37 (0.18-0.56) .53 (0.35-0.71)* .36 (0.18-0.54) - - .85 (0.64-1)* .33 (0.02-0.60) .81 (0.61-1) .76 (0.54-0.98) .67 (0.49-0.85) .58 (0.37-0.79) .66 (0.43-0.89) .40 (0.07-0.73) .63 (0.38-0.88)* .32 (0-0.64) Major depression Induced depression Any Depression (Major & Induced) Any affective diagnosis Psychotic Induced psychosis Any psychotic diagnosis Anxiety Panic with/without agoraphobia Any anxiety diagnosis Personality Antisocial Borderline * p< 0.05 27 Table 3.- Diagnostic reliability of Current DSM-IV Diagnoses with PRISM-IV (n=285) (modified of Hasin et al, 2006) Kappa (SE) Prevalence time1/time2 .75 (0.06) 0.12/0.10 .66 (0.09) 0.08/0.05 .69 (0.06) 0.20/0.15 .36 (0.12 0.05/0.04 Disorder Affective Major Depression, Primary Major Depression, Induced Any Major Depression, Primary or Induced Any Dysthymia, Primary or Induced 1.00 Mania, Induced .67 (0.32) 0.004/0.01 .86 (0.08) 0.04/0.04 .86 (0.08) 0.04/0.04) .75 (0.17) 0.01/0.01 .83 (0.07) 0.06/0.05 .56 (0.16) 0.02/0.02 .24 (2.0) 0.02/0.01 .31 (0.13) 0.03/0.05 .61 (0.10) 0.07/0.06 0.66 (0.18) 0.02/0.01 0.44 (0.12) 0.05/0.04 0.57(0.07) 0.15/0.13 0.69 (0.05) 0.23/0.20 0.67 (0.06) 0.21/0.18 Mania, Primary or Induced Psychosis Schizophrenia Psychotic Primary Psychotic Induced Psychotic Primary or Induced Anxiety Panic Disorder, Primary Generalized Anxiety, Primary Specific Phobia Social Phobia Obsessive Compulsive Post Traumatic Stress Any Anxiety, Primary or Induced Personality Antisocial Personality Borderline Personality 28