Towards Harmonisation of Construction Industry Payment Legislation

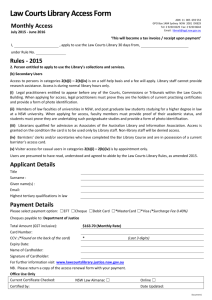

advertisement