- University at Albany

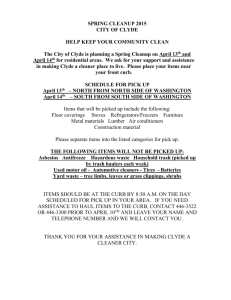

advertisement