Technology And Politics In An Era Of Globalization: An ESSAY

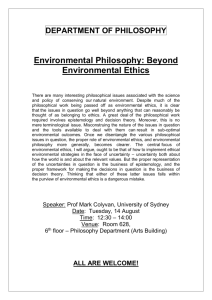

advertisement