The Continuing Relevance of the Milibandian Perspective

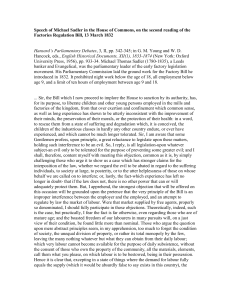

advertisement