Sir John Cam Hobhouse and Richard Oastler on the Factory Bill of

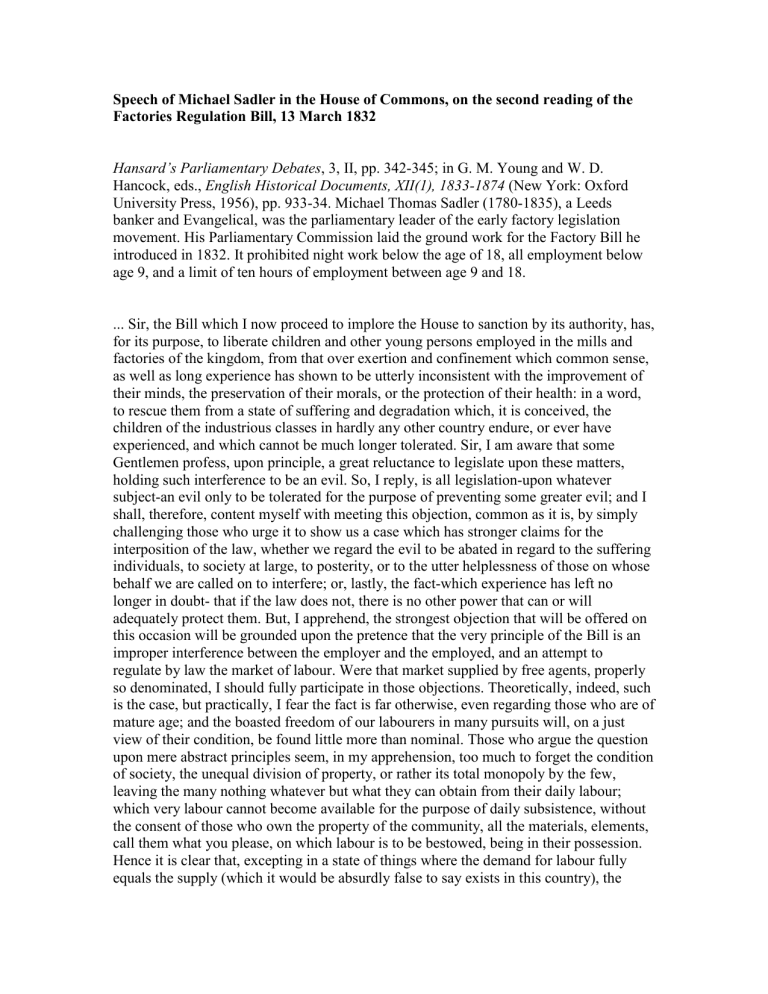

Speech of Michael Sadler in the House of Commons, on the second reading of the

Factories Regulation Bill, 13 March 1832

Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates

, 3, II, pp. 342-345; in G. M. Young and W. D.

Hancock, eds., English Historical Documents, XII(1), 1833-1874 (New York: Oxford

University Press, 1956), pp. 933-34. Michael Thomas Sadler (1780-1835), a Leeds banker and Evangelical, was the parliamentary leader of the early factory legislation movement. His Parliamentary Commission laid the ground work for the Factory Bill he introduced in 1832. It prohibited night work below the age of 18, all employment below age 9, and a limit of ten hours of employment between age 9 and 18.

... Sir, the Bill which I now proceed to implore the House to sanction by its authority, has, for its purpose, to liberate children and other young persons employed in the mills and factories of the kingdom, from that over exertion and confinement which common sense, as well as long experience has shown to be utterly inconsistent with the improvement of their minds, the preservation of their morals, or the protection of their health: in a word, to rescue them from a state of suffering and degradation which, it is conceived, the children of the industrious classes in hardly any other country endure, or ever have experienced, and which cannot be much longer tolerated. Sir, I am aware that some

Gentlemen profess, upon principle, a great reluctance to legislate upon these matters, holding such interference to be an evil. So, I reply, is all legislation-upon whatever subject-an evil only to be tolerated for the purpose of preventing some greater evil; and I shall, therefore, content myself with meeting this objection, common as it is, by simply challenging those who urge it to show us a case which has stronger claims for the interposition of the law, whether we regard the evil to be abated in regard to the suffering individuals, to society at large, to posterity, or to the utter helplessness of those on whose behalf we are called on to interfere; or, lastly, the fact-which experience has left no longer in doubt- that if the law does not, there is no other power that can or will adequately protect them. But, I apprehend, the strongest objection that will be offered on this occasion will be grounded upon the pretence that the very principle of the Bill is an improper interference between the employer and the employed, and an attempt to regulate by law the market of labour. Were that market supplied by free agents, properly so denominated, I should fully participate in those objections. Theoretically, indeed, such is the case, but practically, I fear the fact is far otherwise, even regarding those who are of mature age; and the boasted freedom of our labourers in many pursuits will, on a just view of their condition, be found little more than nominal. Those who argue the question upon mere abstract principles seem, in my apprehension, too much to forget the condition of society, the unequal division of property, or rather its total monopoly by the few, leaving the many nothing whatever but what they can obtain from their daily labour; which very labour cannot become available for the purpose of daily subsistence, without the consent of those who own the property of the community, all the materials, elements, call them what you please, on which labour is to be bestowed, being in their possession.

Hence it is clear that, excepting in a state of things where the demand for labour fully equals the supply (which it would be absurdly false to say exists in this country), the

employer and the employed do not meet on equal terms in the market of labour; on the contrary, the latter, whatever be his age, and call him as free as you please, is often almost entirely at the mercy of the former: he would be wholly so were it not for the operation of the Poor-laws, which are a palpable interference with the market of labour, and condemned as such by their opponents. Hence it is, that labour is so imperfectly distributed, and so inadequately remunerated, that one part of the community is overworked, while another is wholly without employment; evils which operate reciprocally upon each other, till a country which might afford a sufficiency of moderate employment for all, exhibits at one and the same time part of its inhabitants reduced to the condition of slaves by over exertion, and another to that of paupers by involuntary idleness. In a word, wealth, still more than knowledge, is power, and power, liable to abuse whenever vested, is least of all free from tyrannical exercise, when it owes its existence to a sordid source.

Hence have all laws, human or divine, attempted to protect the labourer from the injustice and cruelty which are too often practised upon him. Our Statute-book contains many proofs of this, and especially in its provision for the poor. . . .